Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

In a 1976 NBC interview on the significance of the Viking 1 landing on Mars, astronomer Carl Sagan likened our space program to watching a dandelion gone to seed: “I can’t help but think of this as an epochal moment in planetary exploration. If you can imagine, a sort of a very patient observer, observing the earth for its four and half billion-year lifetime: for all of that period, lots of things came onto the earth, but nothing left it. And now just in the last 10 years, things are spewing off the earth.”

Apartments in Soho, New York City (photo by Nina Munteanu)

The Onset of the Anthropocene & the Great Acceleration

In a Guardian article entitled “The Holocene hangover: it is time for humanity to make fundamental changes”, Fredrick Albritton Jonsson examines Amitav Ghosh’s interpretation of climate change and considers the need to acknowledge Earth’s own powerful and changing identity—particularly through the face of climate change.

Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that we no longer belong—like Cooper was suggesting in the movie Interstellar?

That we’ve largely orchestrated these changes may be considered ironic—or is it simply inevitable? For me, as an ecologist, this is not a new concept. Ecological succession is the process of ecosystem change and development over time (usually following a disturbance) as an establishing species impacts and alters its environment to eventually make the environment less suited to it and more to another species, which will replace it. Succession only stops when a climax community—which is in equilibrium with a stable environment—establishes. This climax stage can persist indefinitely—until the next environmental disturbance, that is. Succession occurs everywhere in Nature; examples include the recolonization of Mount St. Helen following the volcanic eruption. Natural succession occurs in human society as well. A good example can be found in any city. My landscape architect son described the natural process of “gentrification” in a large city: a process of renovation and revival of deteriorated urban areas through an influx of more affluent residents, resulting in increased property values and a displacement of lower-income families and businesses. Inherent in succession is movement and flow—something Nature is very familiar with and uses well.

“Our planet is changing into a strange and unstable new environment, in a process seemingly outside technological control,” writes Jonsson, who laments in a disillusioned patriarchal voice: “The fossil fuels that once promised mastery over nature have turned out to be tools of destruction, disturbing the basic biogeochemical processes that make our world habitable [for us]. Even the recent past is no longer what we thought it was.”

Jonsson then unleashes a litany of examples where humanity has imposed global change, including: climate change; reduced biodiversity of ecosystems; acidification of marine life and oceans capacity to absorb carbon dioxide; fresh water scarcity; ozone depletion, which threatens atmospheric stability; and disruption of global nitrogen and phosphorus cycles—to mention a few. “Indeed,” says Jonsson, “the planet’s biosphere bears so many marks of anthropogenic influence that it is no longer possible to [distinguish] between the realm of wilderness and the world of human habitation.”

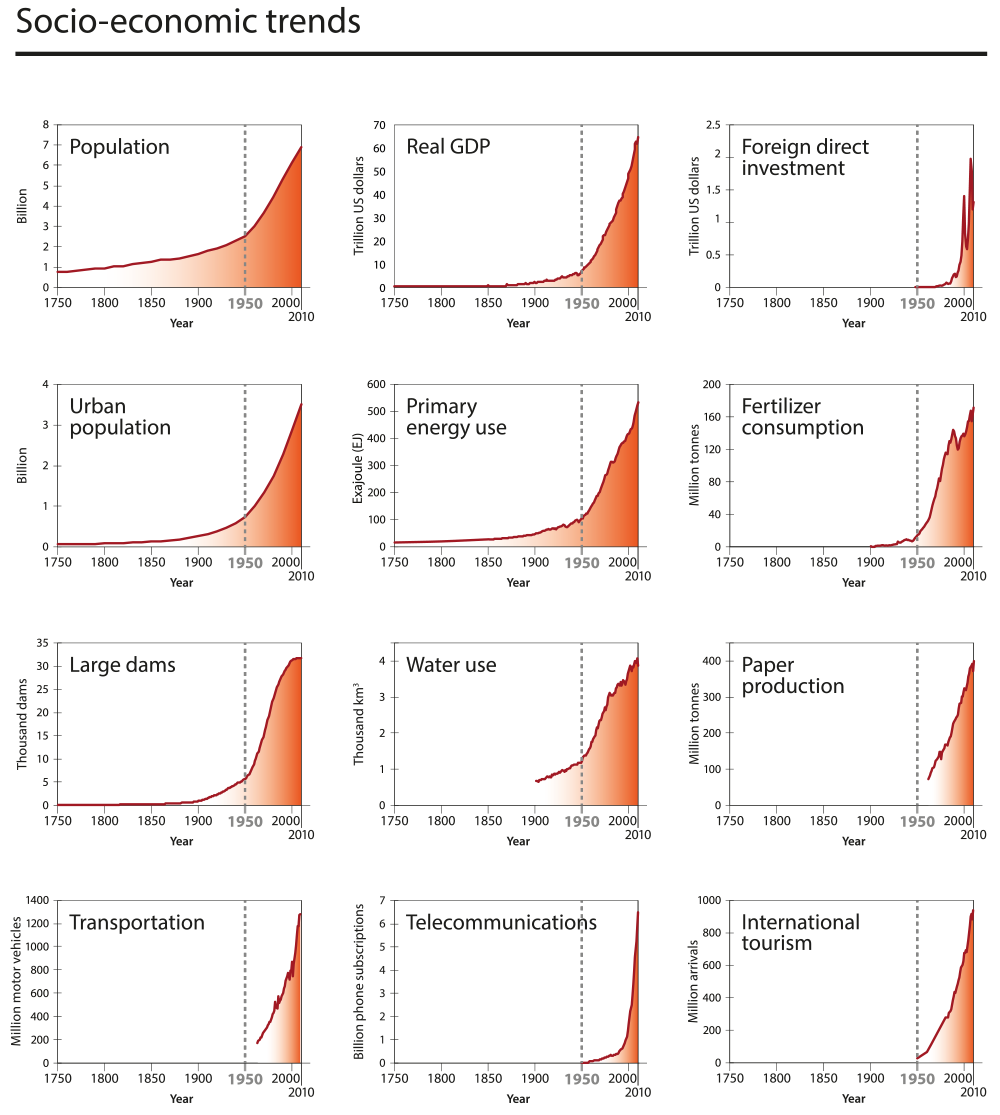

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II.

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II.

The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society.

The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society.

From the devices we carry to the lives we lead, everything is getting faster, faster. The International Geosphere-Bioshpere Programme writes that “the last 60 years have without doubt seen the most profound transformation of the human relationship with the natural world in the history of humankind.” They suggest that the second half of the 20th Century is unique in the history of human existence. “Many key indicators of the functioning of the Earth system are now showing responses that are, at least in part, driven by the changing human imprint on the planet. The human imprint influences all components of the global environment – oceans, coastal zone, atmosphere, and land.”

While this notion rings hubristic, there is no question that humanity is now a major driver of planetary change: from tipping the Earth’s axis through the creation of massive water reservoirs and diverting a third of Earth’s available fresh water to increasing carbon dioxide to a levels found 800,000 years ago—changing global climate.

Geologists and historians discussed how the Anthropocene Epoch would best be identified by observers in a distant future. “Among the plausible candidates proposed are micro-plastics, metal alloys, and artificial isotopes,” writes Jonsson. “Such stratigraphic markers must be placed in their historical context. The scientific identification of the Anthropocene with the year 1945 gives us not just a plausible geological end to the Holocene, but also a watershed that fits comfortably with a great body of scholarly work about the historical consequences of World War II.”

The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago.

The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago.

Our Literature in the Anthropocene

In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’”

In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’”

“By failing to engage with climate change, artists and writers are contributing to an impoverished sense of the world, right at the moment when art and literature are most needed to galvanize a grassroots movement in favor of climate justice and carbon mitigation.”

According to Ghosh, the “great derangement” stemmed from a certain kind of rationality. Plots and characters of bourgeois novelists reflected the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depended on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature was gradual and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale, romance novel, and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely were externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse.

Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse.

Jonsson suggests that these Enlightenment ideas are essentially ideological manifestations of Holocene stability, remnants from 11,000 years of small variability in temperature and carbon dioxide levels, giving rise to deep-seated habits and ideas about the resilience of the natural world. “The commitment to indefinite economic growth espoused by the economics profession in the postwar era is perhaps its most triumphant [and dangerous] expression.”

Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking.

Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking.

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.”

In my interview with Mary Woodbury on Eco-Fiction I remind readers that “science fiction is a powerful literature of allegory and metaphor and deeply embedded in culture. By its very nature, SF is a symbolic meditation on history itself and ultimately a literature of great vision. Some of the very best of fiction falls under the category of science fiction, given the great scope of its platform. More and more literary fiction writers are embracing the science fiction genre (e.g., Margaret Atwood, Kuzuo Ishiguro, Michael Chabon, Philip Roth, Iain Banks, David Mitchell); these writers recognize its immense scope and powerful metaphoric possibilities. From science fiction to eco-fiction is a natural process. Exploring large societal and planetary issues is the purview of both.”

In my interview with Mary Woodbury on Eco-Fiction I remind readers that “science fiction is a powerful literature of allegory and metaphor and deeply embedded in culture. By its very nature, SF is a symbolic meditation on history itself and ultimately a literature of great vision. Some of the very best of fiction falls under the category of science fiction, given the great scope of its platform. More and more literary fiction writers are embracing the science fiction genre (e.g., Margaret Atwood, Kuzuo Ishiguro, Michael Chabon, Philip Roth, Iain Banks, David Mitchell); these writers recognize its immense scope and powerful metaphoric possibilities. From science fiction to eco-fiction is a natural process. Exploring large societal and planetary issues is the purview of both.”

Let’s see more. We need it.

You can find an excellent databank of eco-fiction books on Mary Woodbury’s site Eco-Fiction. Mary Woodbury also includes “12 works of climate fiction everyone should read.” Midge Raymond of Literary Hub lists “5 important works of eco-fiction you need to read.” And then there is the Goodreads Listopia for “Best eco-fiction”

My own works of eco science fiction can be found on my author’s website, Nina Muneanu Writer and at a quality bookstore near you.

My own works of eco science fiction can be found on my author’s website, Nina Muneanu Writer and at a quality bookstore near you.

Why not find a work of eco-fiction and share it with someone you care about this Christmas.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Pingback: When the Permafrost Is Gone… | The Meaning of Water

Pingback: The Fifteenth International Writers’ and Artists’ Festival / Le XVe Festival International des écrivains et artistes – Europa SF – The European Speculative Fiction portal

Pingback: The Fifteenth International Writers’ and Artists’ Festival / Le XVe Festival International des écrivains et artistes | Nina Munteanu Writing Coach

Pingback: The 2017 Canadian Water Summit & “Water Is…” – The Meaning of Water

Pingback: On Being a Canadian in The Age of Water – The Meaning of Water

Pingback: On Being a Canadian in The Age of Water | Nina Munteanu Writing Coach

Pingback: Wonder and Reason in The Age of Water | Nina Munteanu Writing Coach

Pingback: How Creative Destruction Embraces Paradox… | Nina Munteanu Writing Coach

Pingback: How Creative Destruction Embraces Paradox… – The Meaning of Water

This article is very informative, with a conceptual analysis as well as books/fiction recently written on such concerns… Good effort, keep updating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Pinky! You’re right… I do need to keep updating it. Excellent advice.

Best,

Nina

LikeLike

Pingback: Science Fiction Asks: Are We Worth Saving? – AURELIA LEO