I recently attended Claudiu Murgan’s signing of his science fiction book Water Entanglement at Indigo in Yorkdale Mall and had a chance to ask him some questions about the book that intrigued me.

I recently attended Claudiu Murgan’s signing of his science fiction book Water Entanglement at Indigo in Yorkdale Mall and had a chance to ask him some questions about the book that intrigued me.

There are several reasons why I found Claudiu’s book particularly intriguing. Apart from the obvious fact that it has two of my favourite words in the title—Water and Entanglement—there were other intriguing aspects about Claudiu’s book, which takes place in near-future Toronto and features a limnologist as main protagonist.

My just finished novel—A Diary in the Age of Water—is also set in near-future Toronto and features a limnologist—which is what I am—as main protagonist. As we compared more and more notes, I had to laugh at how our two novels were also entangled!

Nina and Claudiu at Indigo

The time-period and the issues of both novels were very similar: growing tensions and politics surrounding a crisis of water scarcity in the 2050s and the continued short-sightedness of climate-denying politicians and corporate Earth. Both novels read like seamless slipstream between fiction and reality (mine is written partially as a memoir, which increases this experience); both explore humanity’s potential evolution linked to our relationship with an entity that remains as mysterious as it is common and life-giving. An entity that most indigenous peoples call alive.

Both Claudiu and I embrace concepts of controversial metaphysical characteristics of water. I wrote about much of this in my book Water Is…The Meaning of Water, which Claudiu references in his novel. “Memory”, quantum coherence, the liquid-crystal state, and polarity express through water’s over 70 anomalous properties: phase, density, thermodynamic, material and physical anomalous properties that include adhesion, cohesion, high specific heat, thermal density, viscosity, and surface tension—just to name some.

“Water is the most extraordinary substance. Practically all its properties are anomalous,” writes Nobel laureate and physiologist Albert Szent-Gyorgyi.

Water Entanglement’s book jacket blurb provides an intriguing premise:

“…Since the creation of Earth, water and crystals have woven their paths into a billion-year-long tapestry that has captured the cycles of nature’s evolution. They have observed the appearance of humans and their troubled, but fascinating development, and the energies and vibrations of everything that is part of this amazing eco-system . . . In 2055 water activists fight against irresponsible corporations that pillage the Earth. Hayyin, the hidden identity of Cherry Mortinger, a limnologist, leads the movement. Will she be able to prove that water has memory and is alive and that we could awaken to the possibility of facing a fierce battle against the primordial element that gave us life: WATER?”

INTERVIEW

Nina: What inspired you to write Water Entanglement and why did you set it in Toronto in the near-future?

Claudiu: At the end of the TV interview I gave back in September 2017 when I launched my first novel, The Decadence of Our Souls, the host asked me about my next project. I had an impulse to say that I’m going to write about water. At that time I had no idea about the potential plot and how powerful the message would be. I also think that spending time with you, Nina, and reading Water Is… influenced my subconscious. The Matrix is choosing several authors that are allowed to flow the right messages about water and create the critical point of awareness. I personally know a handful of them that write about water from a deeper level of understanding.

Why Toronto? Because I would like to see Toronto make a firmer stand on various issues that are not ‘politically correct’. The city’s multi-cultural background has created the notion of niceness about us, which is good to have; but at the same time, we can’t allow the big corporations to dictate how to use Canadian fresh-water resources. If the book is read by the right people, then they might get an idea of what could be done.

Nina: Who should read Water Entanglement and why?

Claudiu: I like to believe that WE is a manifesto written as a Sci-Fi novel. A teenager will find things about water that are not taught in school; properties of water that science can’t deny anymore, but also can’t explain. A Sci-Fi reader will enjoy the geo-political scenarios I imagined along with the fact that water is becoming an active participant in the story, a character that is elusive, unpredictable and creates so much havoc. For an environmentalist and for a water activist, reading about the length corporations are willing to go for a profit will only compell them to continue their fight against greed and disrespect for nature. I didn’t write the book with a specific age bracket in mind, nevertheless, there is a nugget of knowledge for any type of reader willing to accept that the way we treat water is wrong, and that access to clean, potable water is a human right, not a luxury.

Nina: Two of your main POV characters are scientists; one is a limnologist (a freshwater scientist) and another a neurosurgeon. Another character is a Cherokee chief; yet another a UN representative. How did you research your characters to realistically express them in your novel?

Claudiu: The more I write the better I get at doing research. And I have to admit how grateful I am for your advice on my first book, The Decadence of Our Souls, that have elephants as main characters. You said: read more about elephants. So I did. I went to the library and borrowed thirteen books about elephants. For WE I read several books on water, but also interacted with you, Nina, a limnologist, helped me see the world from your point of view. As for my other characters, I had the chance to visit UN HQ and interact with some policy makers. In WE there is less red tape and the UN representative has some liberty when making decisions, ignoring some of the political clutches that currently strangle any decent decision with worldwide implications.

Nina: Your protagonist disguises her subversive activist identity beneath a masked being called Hayyin. Hayyin is an Islamic name that means “without obstacles”, “lenient” or “forgiving.” What was your intention in this name and does it play a role in the theme of your book?

Claudiu: I searched for the word water in Aramaic, which is Jesus’s tribe language. There are historic records that mention Aramaic as being the primordial language. Hayyin, the water activist, had to represent a symbol powerful enough to ignite in his followers the desire to fight for water. We all like to identify ourselves with a symbol that is worth fighting or dying for. Without enough water to sustain our growing population, humanity will fade away in a matter of centuries or less, so I thought that a symbol attached to a hidden identity makes the plot more interesting.

Nina: You cover several subjects of hard—and controversial—science in this book (e.g., homeopathy, epitaxy, polywater, etc.). How did you balance these to create a plausible reality in your novel? What did you have to consider?

Claudiu: I’m not a scientist. As an author I took the liberty of pushing the limits of what is known about water. I consider my research based on data that doesn’t need peer-review validation. I trust the scientists and the authors listed under the bibliography page at the end of the book. There are so many intangible things that touch us daily and most of us are not willing to accept them. The way water behaves in Water Entanglement is an intangible concept for ‘non-believers’ … until it happens. Along with a friend scientist, I’m planning to challenge students to start experiments involving water. They have to engage with their surroundings, ask questions and get their own results.

Nina: A pivotal aspect of your story hinges on the concept of structured water and intention. Can you share a little about it?

Claudiu: When doing my research I learned things about water that I couldn’t believe, but finding the same information from multiple sources convinced me that there is truth to it. I’m a strong believer now that water absorbs our intentions, our thoughts, carries them further until the next ‘shore’. Water that was blessed heals people or sickens them if water transports negative energies and harmful thoughts. Our body cells float in structured water and if the quality / properties of such liquid would be able to be maintained, well … we could live forever.

Nina: the tagline for Water Entanglement challenges: “When will we understand that water has memory, water is alive and the time for her to awaken is NOW?” Your book paints a compelling and terrifying awakening: edible seaweeds turning toxic; sacred rivers losing their healing properties; springs diurnally retreating; raging sinkholes, water turning thick. Tell us a little about these choices for water’s reactions.

Claudiu: What characterizes us as human beings is that we don’t take any potential catastrophic event seriously unless it happens. We would rather deal with the repercussions than prevent the cause. See the levies that broke because of the force of Katrina. The government was well aware of what could happen, but invoked lack of funds. In truth it was lack of government will, the political infighting that is common these days.

In WE I had to give water a radical behavior. Water has intuition and she knows human beings so well. She can predict any of our actions and there is no solution other than offering ‘peace’ – a selfless conduct.

Nina: Your book showcases some of the major challenges humanity faces in how we treat water—scarcity, contamination, diversion, commodification and misappropriation through disrespect of water and Nature, generally. There is an obvious need to alter how we treat water and this must ultimately arise from attitude and knowledge. How do you see us changing our attitude to water when most of us live in cities and don’t even know—or care—where our water comes from or what watershed we live in?

Claudiu: Changing attitude could be a generational approach. To become part of the education at all stages from kindergarten to university. We hear in the news that in Las Vegas the fountains and watering the lawns have been banned. In Africa children and their mothers walk kilometers daily to gather water for drinking and cooking; most of the time it is polluted water. Again, the leaders lack the determination to impose stricter rules or allow technologies that could replace some of the daily activities that require water. Over the years, politicians have enforced the idea that any decision of significance has to go through a lengthy process. It shouldn’t be that way if the greater good is paramount and not petty, personal interest.

Nina: Your novel touches on global economic and military pressures by corporations and governments in aggressive water acquisition. In your novel this occurs mostly via American interests overseas. Closer to home, Maude Barlow of the Council of Canadians tells us that water abundance in Canada is a myth and we are too complacent. Her recent book Boiling Point exposes Canada’s long-outdated water regulations, unprotected groundwater reserves, agricultural pollution, industrial waste dumping, water advisories and effects of deforestation and climate change. As stewards of 20% of the world’s freshwater, our precious water is being coveted by many entities—from corporations to governments—and holding our own will be a tricky balancing act. What do you think is Canada’s main challenge in keeping its water protected?

Claudiu: Yes, in my book I mention that we are down to 13% of world’s freshwater resources. I also mention that only smart policy could keep the sharks away. We are not a third-world, tiny, easy-to-intimidate country. We should stand our ground and push back on any such attempt. The government should protect both private and public freshwater sources and even offer support regardless of ownership.

Nina: Your book touches upon corrupt government officials and corporate CEOs in terms of water issues. Various anonymous organizations such as WikiLeaks, Anonymous Group, and individuals—including your main character who uses a mask to maintain her anonymity—play a major role as activists in your book. Do you see this as the most effective way to expose wrongdoing and affect change?

Claudiu: It was already proven that revelations through WikiLeaks have affected the political environment, revealing corruption at high levels of government, secret documents mishandling, transaction from which a handful of people benefited, etc. As far as I know no one has dug deeper into these documents for nuggets of shady deals about commodities such as water (as water is considered a commodity to lessen her important role in our lives). But they are happening in the shadows, overseen by easily bribed politicians that only find happiness in short-term gratification. Hacking corporations that claim they are responsible when it comes to environment and human health, is a civic duty. It reveals the gangrene that affects our world.

Nina: In your novel, you created Water For All (WFA) as a global NGO organization devoted to protecting water by exposing heinous wrongdoings and helping to correct them by helping to pass legislature; what do you see as the largest challenges faced by NGOs today?

Claudiu: In my opinion the water movement is fractured in too many pieces. They all want to do good, but there is no scalability to their initiatives. Funding is somehow scarce and not enough to have a significant impact when divided among so many entities. In Water Entanglement I put forward two concepts that might solve this issue. First, WFA is the unique entity that consolidates as many of the water activists and water-related organizations as possible. So funding for selected projects comes from one source. Second, there is a worldwide strategy addressing sensitive areas and the source of pollution is addressed first. Leaders should come together for such a noble goal, give up their egos and create the critical mass that can overpower the influence of the multi-nationals in the water industry.

Nina: Your novel invokes Mother Nature and repeats the Indigenous peoples’ tautology “protect your mother.” You reiterate that for most Aboriginal nations, women are considered the “Water Keepers.” Your main characters—mostly activists—are women. Your main character, Cherry, is a limnologist and water activist; Romana is the UNWater chair; Ilanda is an enlightened neurosurgeon experimenting with crystal technology to help raise awareness and cognition (her husband runs Vivus Water Inc. that uses desalinization plants to further secure their water business). You also reiterate that water carries a female gender as Chief Landing Eagle says: “Fear the day when water remembers what we have done to her.” Do you see a significant role for women in changing how we view and treat water in the world?

Claudiu: Women in general are more empathic and it is a known fact that a world dominated by a matriarch society is a peaceful one. Seems that women care more about the life they nurture inside them for nine months. They are less egotistic and more willing to forgive. It’s an attitude water needs to survive the ordeal we are putting her through. We need more women as decision makers when it comes to water usage and water preservation. It might be easier for a woman to find and keep the balance on the right side of the thin line we are walking as a species. Crossing it could mean the end of the world.

Claudiu Murgan was born in Romania and has called Canada his home since 1997. He started writing science fiction when he was 11 years old. Since then he met remarkable writers who helped him improve his own trade. His first novel, The Decadence of Our Souls highlights his belief in a potentially better world if the meanings of Love, Gratitude and Empathy could be understood by all of our brothers and sisters. www.ClaudiuMurgan.com.

Claudiu Murgan was born in Romania and has called Canada his home since 1997. He started writing science fiction when he was 11 years old. Since then he met remarkable writers who helped him improve his own trade. His first novel, The Decadence of Our Souls highlights his belief in a potentially better world if the meanings of Love, Gratitude and Empathy could be understood by all of our brothers and sisters. www.ClaudiuMurgan.com.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness— Canadians are writing more

Canadians are writing more  My short story “

My short story “ Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “

Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps.

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps. Emilie Moorhouse of

Emilie Moorhouse of  “…In an interesting scarcity future in which we follow the fate of a character abandoned by her mother, water itself becomes a character. In the second paragraph we’re told that “Water is a shape shifter,” and in the next page we encounter the following description: “Water was paradox. Aggressive yet yielding. Life-giving yet dangerous. Floods. Droughts. Mudslides. Tsunamis. Water cut recursive patterns of creative destruction through the landscape, an ouroboros remembering.” These descriptive musings cleverly turn out to be more than metaphors and tie in directly to the tale’s surprising ending.”—Alvaro Zinos-Amaro,

“…In an interesting scarcity future in which we follow the fate of a character abandoned by her mother, water itself becomes a character. In the second paragraph we’re told that “Water is a shape shifter,” and in the next page we encounter the following description: “Water was paradox. Aggressive yet yielding. Life-giving yet dangerous. Floods. Droughts. Mudslides. Tsunamis. Water cut recursive patterns of creative destruction through the landscape, an ouroboros remembering.” These descriptive musings cleverly turn out to be more than metaphors and tie in directly to the tale’s surprising ending.”—Alvaro Zinos-Amaro,  Water Is… The Meaning of Water

Water Is… The Meaning of Water

But Joshua is a spirited creek – in spite of all it has been through, Joshua Creek is among the top two urban creeks for healthy water quality, and is still inhabited by a variety of aquatic animals like small fish and insects. Joshua Creek is home to forests, wetlands and thickets with around 150 plant species, and provides an important natural habitat corridor for the movement of birds and other animals, including migratory species. Rather than exclusively shrinking, there are also areas of Joshua Creek that are actually in the middle of regrowing their forests, and in spite of everything, Joshua still retains some beautiful gems of natural areas.”

But Joshua is a spirited creek – in spite of all it has been through, Joshua Creek is among the top two urban creeks for healthy water quality, and is still inhabited by a variety of aquatic animals like small fish and insects. Joshua Creek is home to forests, wetlands and thickets with around 150 plant species, and provides an important natural habitat corridor for the movement of birds and other animals, including migratory species. Rather than exclusively shrinking, there are also areas of Joshua Creek that are actually in the middle of regrowing their forests, and in spite of everything, Joshua still retains some beautiful gems of natural areas.”

Saryn and Nina discuss some of water’s controversial properties and the claims about water and how geopolitics plays a role in this. She brings in her own career as a limnologist and how she broke away from her traditional role of scientist to create a biography of water that anyone can understand—at the risk of being ostracized by her own scientific community (just as Carl Sagan and David Suzuki were in the past).

Saryn and Nina discuss some of water’s controversial properties and the claims about water and how geopolitics plays a role in this. She brings in her own career as a limnologist and how she broke away from her traditional role of scientist to create a biography of water that anyone can understand—at the risk of being ostracized by her own scientific community (just as Carl Sagan and David Suzuki were in the past). Nina responded with, “The why of things and hence the subtitle: the Meaning of Water. What does it mean to you… That’s what’s missing a lot of the time. We are bombarded with information, knowledge and prescriptions but the subliminal argument underneath—the why—why should it matter to me—is often missing. That becomes the sub-text. And it’s nice when it comes to the surface.”

Nina responded with, “The why of things and hence the subtitle: the Meaning of Water. What does it mean to you… That’s what’s missing a lot of the time. We are bombarded with information, knowledge and prescriptions but the subliminal argument underneath—the why—why should it matter to me—is often missing. That becomes the sub-text. And it’s nice when it comes to the surface.”

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the  Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions. Nina Munteanu’s “The Way of Water” and the anthology in which it appears was recently praised by Emilie Moorhouse in Prism International Magazine, in a review entitled

Nina Munteanu’s “The Way of Water” and the anthology in which it appears was recently praised by Emilie Moorhouse in Prism International Magazine, in a review entitled  “The Way of Water” (La natura dell’acqua) was translated by Fiorella Smoscatello for Mincione Edizioni. Simone Casavecchia of SoloLibri.net, describes “The Way of Water” in her review of the Italian version:

“The Way of Water” (La natura dell’acqua) was translated by Fiorella Smoscatello for Mincione Edizioni. Simone Casavecchia of SoloLibri.net, describes “The Way of Water” in her review of the Italian version:

“The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s

“The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

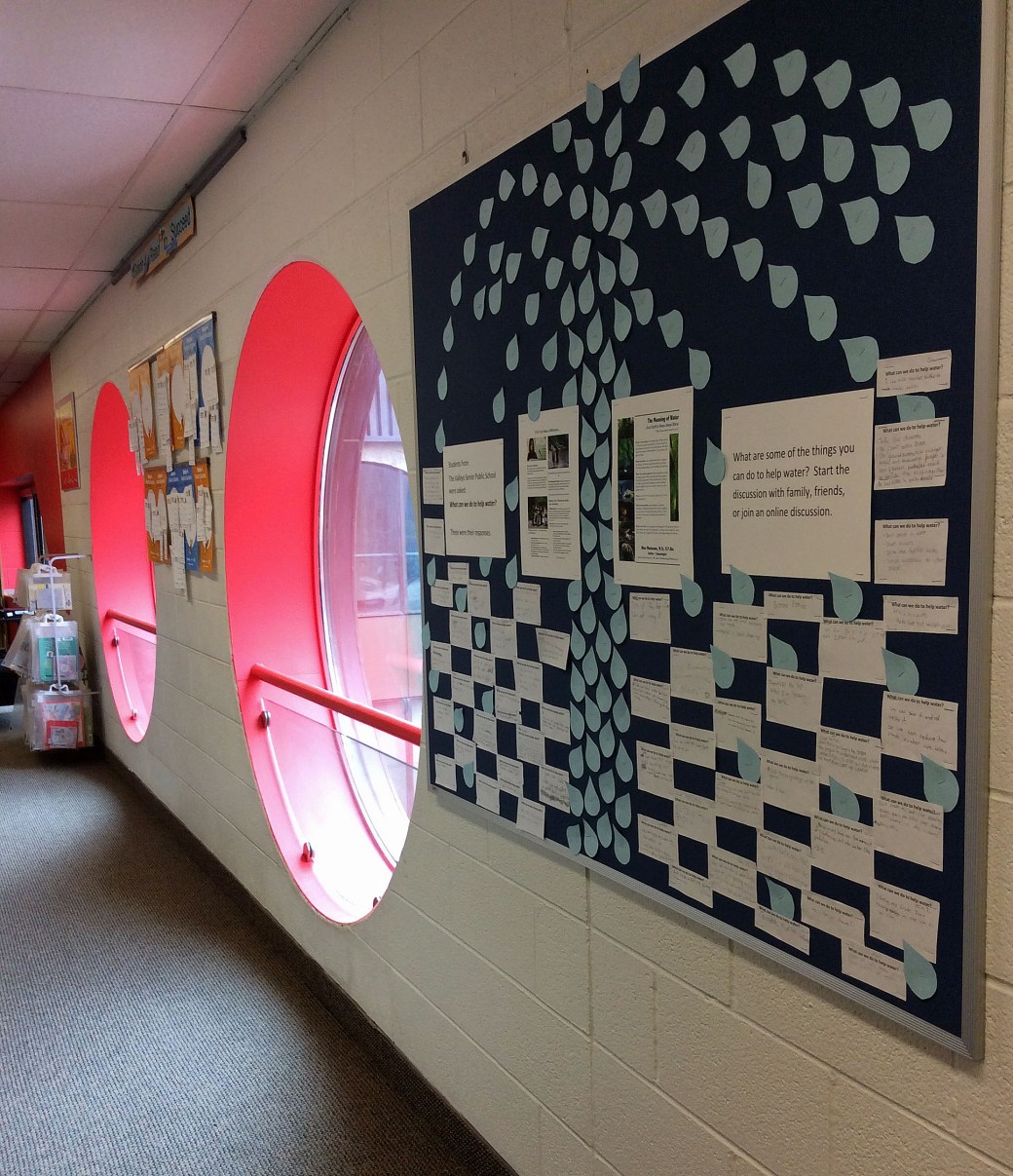

I started the talk by explaining that I’m a limnologist—someone who studies freshwater—and that water is still a mysterious substance, even for those who make it their profession to study. After informing them of water’s ubiquity in the universe—it’s virtually everywhere from quasars to planets in our solar system—I reminded them that the water that dinosaurs drank during the Paleozoic Era is the same water that you and I are drinking.

I started the talk by explaining that I’m a limnologist—someone who studies freshwater—and that water is still a mysterious substance, even for those who make it their profession to study. After informing them of water’s ubiquity in the universe—it’s virtually everywhere from quasars to planets in our solar system—I reminded them that the water that dinosaurs drank during the Paleozoic Era is the same water that you and I are drinking.

You can read so much more about water in my book

You can read so much more about water in my book  I was born on this day, some sixty+ years ago, in the small town of Granby in the Eastern Townships to German-Romanian parents. Besides its zoo—which my brother, sister and I used to visit to collect bottles for a finder’s fee at the local treat shop—the town had no particular features. It typified French-Canada of that era.

I was born on this day, some sixty+ years ago, in the small town of Granby in the Eastern Townships to German-Romanian parents. Besides its zoo—which my brother, sister and I used to visit to collect bottles for a finder’s fee at the local treat shop—the town had no particular features. It typified French-Canada of that era.

As efforts are made to reconcile the previous wrongs to Indigenous peoples within Canada and as empowering stories about environment are created and shared, Canada carries on the open and welcoming nature of our Indigenous peoples in encouraging immigration. In 2016, the same year the American government announced a ban on refugees, Canada took in 300,000 immigrants, which included 48,000 refuges. Canada encourages citizenship and around 85% of permanent residents typically become citizens. Greater Toronto is currently the most diverse city in the world; half of its residents were born outside the country. Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Montreal are not far behind.

As efforts are made to reconcile the previous wrongs to Indigenous peoples within Canada and as empowering stories about environment are created and shared, Canada carries on the open and welcoming nature of our Indigenous peoples in encouraging immigration. In 2016, the same year the American government announced a ban on refugees, Canada took in 300,000 immigrants, which included 48,000 refuges. Canada encourages citizenship and around 85% of permanent residents typically become citizens. Greater Toronto is currently the most diverse city in the world; half of its residents were born outside the country. Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Montreal are not far behind. Writer and essayist Ralston Saul suggests that Canada has taken to heart the Indigenous concept of ‘welcome’ to provide, “Space for multiple identities and multiple loyalties…[based on] an idea of belonging which is comfortable with contradictions.” Of this Forman writes:

Writer and essayist Ralston Saul suggests that Canada has taken to heart the Indigenous concept of ‘welcome’ to provide, “Space for multiple identities and multiple loyalties…[based on] an idea of belonging which is comfortable with contradictions.” Of this Forman writes: And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.” Canada is a true multi-cultural nation that celebrates its diversity: the wholes that make up the wholes.

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.” Canada is a true multi-cultural nation that celebrates its diversity: the wholes that make up the wholes. We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

After she and fellow colonists crash land on the hostile jungle planet of Mega, rebel-scientist Izumi, widower and hermit, boldly sets out against orders on a hunch that may ultimately save her fellow survivors—but may also risk all. As the other colonists take stock, Izumi—obsessed with discovery and the need to save lives—plunges into the dangerous forest, which harbors answers, not only to their freshwater problem, but ultimately to the nature of the universe itself. Mega was a goldilocks planet—it had saltwater and supported life—but the planet also possessed magnetic-electro-gravitational anomalies and a gravitational field that didn’t match its size and mass. The synchronous dance of its global electromagnetic field suggested self-organization to Izumi, who slowly pieced together Mega’s secrets: from its “honeycomb” pools to the six-legged uber-predators and jungle infrasounds—somehow all connected to the water. Still haunted by the meaningless death of her family back on Mars, Izumi’s intrepid search for life becomes a metaphoric and existential journey of the heart that explores how we connect and communicate—with one another and the universe—a journey intimately connected with water.

After she and fellow colonists crash land on the hostile jungle planet of Mega, rebel-scientist Izumi, widower and hermit, boldly sets out against orders on a hunch that may ultimately save her fellow survivors—but may also risk all. As the other colonists take stock, Izumi—obsessed with discovery and the need to save lives—plunges into the dangerous forest, which harbors answers, not only to their freshwater problem, but ultimately to the nature of the universe itself. Mega was a goldilocks planet—it had saltwater and supported life—but the planet also possessed magnetic-electro-gravitational anomalies and a gravitational field that didn’t match its size and mass. The synchronous dance of its global electromagnetic field suggested self-organization to Izumi, who slowly pieced together Mega’s secrets: from its “honeycomb” pools to the six-legged uber-predators and jungle infrasounds—somehow all connected to the water. Still haunted by the meaningless death of her family back on Mars, Izumi’s intrepid search for life becomes a metaphoric and existential journey of the heart that explores how we connect and communicate—with one another and the universe—a journey intimately connected with water. Fingal’s Cave

Fingal’s Cave Fingal’s Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The cave is formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns in a Paleocene lava flow (similar to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland). Its entrance is a large archway filled by the sea. The eerie sounds made by the echoes of waves in the cave, give it the atmosphere of a natural cathedral. Known for its natural acoustics, the cave is named after the hero of an epic poem by 18th century Scots poet-historian James Macpherson. Fingal means “white stranger”.

Fingal’s Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The cave is formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns in a Paleocene lava flow (similar to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland). Its entrance is a large archway filled by the sea. The eerie sounds made by the echoes of waves in the cave, give it the atmosphere of a natural cathedral. Known for its natural acoustics, the cave is named after the hero of an epic poem by 18th century Scots poet-historian James Macpherson. Fingal means “white stranger”.