Gargantua Black Hole in “Interstellar)

Science fiction, which Ted Gioia of The San Francisco Chronicle calls “conceptual fiction” explores the interaction of humanity with some larger phenomenon that involves science. SF writer Robert J. Sawyer calls it the fiction of the large. Large ideas, large circumstance, large impact. Science fiction is a powerful literature of allegory and metaphor that is deeply embedded in culture. By capturing context, SF is a symbolic meditation on history itself and ultimately a literature of great vision.

Science fiction is the literature of consequence that, in exploring large issues faced by humankind, can provide an important vehicle in raising environmental awareness and a planetary consciousness. Much of science fiction is currently focused in that direction. Terms such as eco-fiction, climate fiction and its odd cousin “cli-fi”, have embedded themselves in science fiction terminology; this fiction has attracted a host of impressive authors who write to its calling: Margaret Atwood, Emmi Itäranta, Jeff VanderMeer, Richard Powers, Barbara Kingsolver, Upton Sinclair, Ursula Le Guin, JoeAnn Hart, Frank Herbert, John Yunker, Kim Stanley Robinson, James Bradley, Paolo Bacigalupi, Nathaniel Rich, David Mitchell, Junot Diaz, Claire Vaye Watkins, J.G. Ballard, Marcel Theroux, Thomas Wharton—just to name a few. The list seems endless. Of course, I’m one of them too. Many of these works explore and illuminate environmental degradation and ecosystem collapse at the hands of humanity.

Lately, science fiction is asking the question of whether humanity is worth saving and at what expense?

It’s a valid question.

As the first swell of the climate change tidal wave laps at our feet, we are beginning to see the planetary results of what humanity has created and exacerbated. Humanity has in many ways reached a planetary tipping point; a threshold that will be felt by all aspects of our planet, both animate and inanimate as the planet’s very identity shifts.

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the Anthropocene Epoch—the age of humanity. The term arose not from hubris, but in recognition of our ubiquitous and overwhelming influence on large systems and planetary cycles.

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the Anthropocene Epoch—the age of humanity. The term arose not from hubris, but in recognition of our ubiquitous and overwhelming influence on large systems and planetary cycles.

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the Anthropocene Epoch too shall end? Is that when we end … or transcend?

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the Anthropocene Epoch too shall end? Is that when we end … or transcend?

A tidal wave of TV shows and movies currently explore—or at least acknowledge—the devastation we are forcing on the planet. Every week Netflix puts out a new show that follows this premise of Earth’s devastation: 3%; The 100; The Titan; Orbiter 9; even Lost in Space.

Are we worth saving? Below are a few examples of movies, TV series I’ve lately watched and books I’ve lately read that address this key question to an irresponsible humanity that seems unconcerned that we are destroying our very home. In some the question is subtly implied; in others, not so subtle.

Battlestar Galactica (2004)

In the pilot of Battlestar Galactica, Commander Adama gives an impromptu speech (not the one he prepared; but one provoked by an argument with his son), which resonates throughout the entire series as cylon and human must refashion themselves and their relationship to each other while they discover the cyclical recursive nature of all things and that “all this has happened before and will again.”

The Galactica ship is about to be decommissioned and has now become a museum since the cylons have disappeared forty years ago. The great battle between the cylons and their human creators ended forty years ago with the cylons disappearing suddenly, never to be heard from again. But that is about to change; as Adama gives his speech, the first strike occurs, followed by a massive attack that almost wipes out the human race.

Commander Adama

In his speech Adama says:

“The cost of wearing the uniform can be high…but sometimes it’s too high. When we fought the cylons, we did it to save ourselves from extinction. But we never answered the question why. Why are we as a people worth saving. We still commit murder because of greed, spite and jealousy. And we still visit all of our sins upon our children. We refuse to accept the responsibility for anything that we’ve done. Like we did with the cylons. We decided to play God. Create life. When that life turned against us, we comforted ourselves in the knowledge that it really wasn’t our fault, not really. You cannot play God then wash your hands of the things you’ve created. Sooner or later the day comes when you can’t hide from the things that you’ve done anymore.”

Interstellar (2014)

Voyaging to Gargantua Black Hole

Cooper explores the ice planet

Early on in the science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world is a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.”

After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” The human-centred hubris in this colonialist mentality lies in what we have left behind—a planet suffocating from the effects of humanity’s careless and thoughtless activities. What Interstellar circles but does not address is the all-important question: is humanity even worth saving?

The suggestion during the movie’s final moments, is that we are worth saving because we will transcend into wiser benevolent beings: a hopeful gesture based on the power of love.

The Three Body Problem (2014)

Cixin Liu’s The Three Body Problem was set against the backdrop of China’s Cultural Revolution, because, says Liu, “The Cultural Revolution provides the necessary background for the story. The tale I wanted to tell demanded a protagonist [Ye Wenjie] who gave up all hope in humanity and human nature. I think the only episode in modern Chinese history capable of generating such a response is the Cultural Revolution. It was such a dark and absurd time that even dystopias like 1984 seem lacking in imagination in comparison.” (I suppose Cixin did not experience the holocaust of Germany or Stalin’s purge in the Soviet Union).

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

“Ye Wenjie could only describe the deforestation that she witnessed as madness. The tall Dahurian larch, the evergreen Scots pine, the slim and straight white birch, the cloud-piercing Korean aspen, the aromatic Siberian fir, along with black birch, oak, mountain elm, Chosenia arbutifolia—whatever they laid eyes on, they cut down. Her company wielded hundreds of chain saws like a swarm of steel locusts, and after they passed, only stumps were left.

The fallen Dahurian larch, now bereft of branches, was ready to be taken away by tractor. Ye gently caressed the freshly exposed cross section of the felled trunk. She did this often, as though such surfaces were giant wounds, as though she could feel the tree’s pain… The trunk was dragged away. Rocks and stumps in the ground broke the bark in more places, wounding the giant body further. In the spot where it once stood, the weight of the fallen tree being dragged left a deep channel in the layers of decomposing leaves that had accumulated over the years. Water quickly filled the ditch. The rotting leaves made the water appear crimson, like blood.”

Already cynical about humanity’s failed culture and science—Wenjie acquires a contraband copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. The book and revelation she experiences from it sets in motion her remaining trajectory.

“More than four decades later, in her last moments, Ye Wenjie would recall the influence Silent Spring had on her life. The book dealt only with a limited subject: the negative environmental effects of excessive pesticide use. But the perspective taken by the author shook Ye to the core. The use of pesticides had seemed to Ye just a normal, proper—or, at least, neutral—act, but Carson’s book allowed Ye to see that, from Nature’s perspective, their use was indistinguishable from the Cultural Revolution, and equally destructive to our world. If this was so, then how many other acts of humankind that had seemed normal or even righteous were, in reality, evil?

As she continued to mull over these thoughts, a deduction made her shudder: Is it possible that the relationship between humanity and evil is similar to the relationship between the ocean and an iceberg floating on its surface? Both the ocean and the iceberg are made of the same material. That the iceberg seems separate is only because it is in a different form. In reality, it is but a part of the vast ocean.…It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair. To achieve moral awakening required a force outside the human race.

This thought determined the entire direction of Ye’s life.”

Ye is sent to the Chinese version of SETI and succeeds in sending a message to aliens on Trisolaris. Despite a warning that the Trisolarians mean only to invade, Wenjie invites them to Earth. To ensure the arrival of the Trisolaris aliens, she collaborates with Michael Evans—an oil billionaire’s son who is disgusted with human’s destruction of Nature. Despising humankind in its current state, Wenjie believes the aliens will somehow ensure humanity’s transcendence; Evans, however, applauds the coming invasion as the best route to achieve the eradication of humanity and the survival of the rest of the planet.

The Expanse (2015)

Bobby Draper and crew face an unknown enemy on Ganymede Station

Naomi and Holden

The Expanse is a stylish and intelligent science fiction (SF) TV series (on Syfy Channel) based on books by James S.A. Corey. It is set 200 years in the future when humanity has colonized the moon, Mars and the Asteroid Belt to mine minerals and water. This sophisticated SF film noir thriller elevates the space opera sub-genre with a meaningful metaphoric exploration of issues relevant in today’s world—issues of resource allocation, domination & power struggle, values, prejudice, and racism. Ever-expanding outward in a frantic search for resources as Earth’s own resources fester in pollution and Earthers languish on “the dole”, colonizing humans on Mars and the Belt have even changed their physiology, culture, language and identity.

The tag line of the first season poster for The Expanse reads: “We’ve gone too far.” The series begins on Ceres with a Belter activist inciting a crowd with talk about how Mars and Earth are squeezing Belters for all their water.

Avasarala and DeGraaf

Not so subtle signs of our destructive jingoistic determination runs through this series (now in its third season). After Under Secretary Avasarala’s friend Degraaf (Earth ambassador to Mars) becomes a casualty of one of her intel games, Degraaf quietly shares: “You know what I love about Mars?… They still dream; we gave up. They are an entire culture dedicated to a common goal: working together as one to turn a lifeless rock into a garden. We had a garden and we paved it.”

Miller and Dawes sparring

Ceres born militant activist Anderson Dawes confides to Detective Miller: “All we’ve ever known is low G and an atmosphere we can’t breathe. Earthers,” he continues, “get to walk outside into the light, breathe pure air, look up at a blue sky and see something that gives them hope. And what do they do? They look past that light, past that blue sky. They see the stars and they think ‘mine’… Earthers have a home; it’s time Belters had one too.”

The Martians hold Earth in contempt for their cavalier approach to their resources. Onboard the MCRN Donnager, Martian Lopez asks his prisoner Jim Holden if he misses Earth and Holden grumbles, “If I did, I’d go back.” Lopez then dreamily relates stories his uncle told him about Earth’s “endless blue sky and free air everywhere. Open water all the way to the horizon.” Then Lopez turns a cynical eye back on Holden. “I could never understand your people. Why, when the universe has bestowed so much upon you, you seem to care so little for it.” Holden admits, “Wrecking things is what Earthers do best…”

Martian marine Bobbie Draper

Then he churlishly adds, “Martians too, by the look of your ship.” Lopez retorts, “We are nothing like you. The only thing Earthers care about is government handouts. Free food, free water. Free drugs to forget the aimless lives you lead. You’re shortsighted. Selfish. It will destroy you. Earth is over, Mr. Holden. My only hope is that we can bring Mars to life before you destroy that too.” When a Ceres-born Detective Miller asks Holden why he left Earth, Holden responds: “everything I loved there was being destroyed.”

The show makes a few opportunities to point out what we are doing to our planet. Cherish what you have. Cherish your home and take care of it. We’re reminded that time and again, we aren’t doing a good job of that. When Martian marine Bobbie Draper travels to Earth for the first time and is compelled to find the ocean, she is met with the stench of sewage and garbage; yet, she looks longingly out to sea, seeing a dream…

Incorporated (2016)

Incorporated is a science fiction thriller that provides a chilling glimpse of a post-climate change dystopia. Created by David and Alex Pastor and produced by Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Ted Humphrey and Jennifer Todd, the TV show (filmed in Toronto, Canada) opens in 82 °F Milwaukee in November 2074 after environmental degradation, water level rise, widespread famine and mismanagement have bankrupted governments. We learn later that Milwaukee Airport served as a FEMA climate relocation centre that resembles an impoverished shantytown. In the wake of the governments demise, a tide of multinational corporations has swept in to control 90% of the globe and ratified the 29th amendment, granting them total sovereignty.

Corporations fight a brutal covert war for market share and dwindling natural resources. Like turkey vultures circling overhead, they position themselves for what’s left after short-sighted government regulations, lack of corporate check and FEMA mismanagement have ‘had their way’ with the planet. The world is now a very different place. There is no Spain or France. Everything south of the Loire is toxic desert; submerged New York City reduced to a punch line in a joke. Reykjavik and Anchorage are sandy beach destinations and Norway is the new France—at least where champagne vineyards are concerned. Asia and Canada are coveted for their less harsh climates.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

“You look to Incorporated for dystopian fiction that expresses our current anxieties,” writes Jeff Jensen of Entertainment Weekly. “What you get is fitful resonance that makes you realize it might be too soon for any show to meet that challenge.”

Or is it more that we may be too late… The question of whether we are worth saving is never asked—it is shown: and perhaps the real reason the show was cancelled after one season.

3% (2016)

3% is set in the near future after the planet has fallen into a divided haves and have-nots through environmental calamity. Three percent of the population live well on an island in the Atlantic Ocean, called Offshore (Mar Alto). The remaining 97% struggle Inland with poverty and scarcity. A selection process lies between them.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

By the time Season 1 is over, candidates will have committed a full range of desperate and unsavory acts to make the cut—the stakes are high, after all: secure a position in the 3% elite or die in squalor and poverty. After being eliminated during the interview process, one youth throws himself off a balcony of the testing centre.

3% examines the motivations and paradoxes of heroism and villainy, sometimes turning them on their sides until they touch with such intimacy you can’t tell them apart. At its deepest, 3% explores the nature of humanity—from its most glorious to its most heinous—under the stress of scarcity and uncertainty. How we behave under these polarizing challenges ultimately determines who we are. The question of whether we are worth saving is explored through the subtleties—or not so subtle aspects—of a fascist society that practices exterminism.

Missions (2018)

Missions is a French TV series about the race by two ships—the Ulysses and Z1, representing two ambitious billionaires—to explore Mars. It opens in 1967 with the heroic sacrifice of Vladimir Komarov, the pilot of the faulty Soyuz 1, who knew he would not return and accepted his mission to save his best friend, Yuri Gagarin (his backup). This heroic act is mirrored in the last episode of Season 1 with a similar selfless act of heroism by Ulysses psychologist Jeanne Renoir to save her crewmembers who are trying to escape a fatal dust storm on Mars.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

Amid developments between the two ship teams in which self-serving agendas, paranoias and blind ambition reign, Jeanne shares a vision with an entity that looks like Komarov, in which he tells her: “Yes, people dream of other places, while they can’t even look after their own planet…You must remember your past in order to think about your future. Do you think Earth has a future?” When Jeanne says she doesn’t know, Komarov challenges, “Yes, you do. They eat their marshmallow right away, when they could have two. Or a thousand. Do you think humanity can continue like that?” Of course she doesn’t think so. Komarov continues, “People have chosen a brief but exciting life. Your species burns the candle at both ends. You know this. And it terrifies you…”

Jeanne Renoir

From the beginning, we glimpse a surreal connection between Jeanne and Komarov and ultimately between Earth and Mars: from her childhood admiration for the Russian’s heroism on Earth to the “visions” they currently share that link key elements of her past to Mars and Komarov’s strange energy-giving powers, to Jeanne’s own final act of heroism on Mars.

As the storyline develops, linking Earth and Mars in startling ways, and as various agendas—personal missions—are revealed, we finally clue in on the main question that “Missions”—through Komarov and finally Jeanne—is asking: are we worth saving?

The Beyond (2018)

In The Beyond, the sudden appearance of a wormhole causes the disappearance of astronaut Jim Marcell during EVA on Earth’s orbiting space station, followed by associated calamitous phenomena on Earth. Giant dark spherical clouds then appear and settle all over the Earth, disrupting the world’s population, and setting in motion a series of fearful and aggressive reactions by various sectors of humanity.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The film ends with a cautious hope, implicitly asking that big question: are we (humanity) worth saving? When Jessica asks why humanity was offered a second chance by benevolent beings way beyond our comprehension, the returned Jim Marcell (currently a spokesman for the aliens) shows her the GAD (Golden Archive Drive with video images of Earth and humanity—basically our “hello” message to extra-solar life like the one placed onboard NASA’s Pioneer missions) that had accompanied the ship into the wormhole. The message displayed scenes of mothers and their children, people laughing in joy; it also showed scenes of other aspects of this beautiful planet worth saving: the ocean surf, the forests and wildlife. In our hubris, we have lost our perspective about this planet. Perhaps, it wasn’t so much humanity the alien beings intended to save but the Earth itself; we just come along with it. The Earth is, after all, a beautiful, vital and unique world, rich with life-giving water, trees, animals, creatures of all kinds in a diverse network of flowing and evolving beauty. A planet worth saving and that, frankly, functions better without us.

So, the question remains: is humanity worth saving? For centuries we have hubristically and disrespectfully used, discarded and destroyed just about everything on this beautiful planet. According to the World Wildlife Federation, 10,000 species go extinct every year. That’s mostly on us. They are the casualty of our selfish actions. We’ve become estranged from our environment, lacking connection and compassion. That has translated into a lack of consideration—even for each other. In response to mass shootings of children in schools, the U.S. government does nothing to curb gun-related violence through gun-control measures; instead they suggest arming teachers. We light up our cigarettes in front of people who don’t smoke and blow cancer-causing second-hand smoke in each other’s faces. We litter our streets and we refuse to pick up after others even if it helps the environment and provides beauty for self and others. The garbage we thoughtlessly discard pollutes our oceans with plastic and junk, hurting sea creatures and the ocean ecosystem in unimaginable ways. We consume and discard without consideration.

We do not live lightly on this planet.

We tread with incredibly heavy feet. We behave like bullies and, as The Beyond points out, our inclination to self-interest makes us far too prone to suspicion and distrust: when we meet the unknown, we tend to respond with fear and aggression over curiosity, hope and kindness.

Something we need to work on if we are going to survive.

Science fiction—the highest form of metaphoric and visionary art—is telling us something. Are we paying attention?

References:

Carson, Rachel. 1962. “Silent Spring.” Houghton Mifflin. 336pp.

Corey, James S.A. “The Leviathan Wakes.” Orbit. 592 pp.

Liu, Cixin. 2014. “The Three Body Problem.” Tor Books. 400pp.

Once upon a time, there will be one absolute ruler who we, the people, call the Supreme Leader (May He Rule Forever). The Supreme Leader will hate immigrants, writers, scientists, environment and extinct species. We, the people under his rule, will be proud to live in our pure and glorious Motherland. Because we’ll have little to eat, no entertainment, no self-respect, no freedom, no rights, and no access to the outside world, we’ll be happy.

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps.

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps. Emilie Moorhouse of

Emilie Moorhouse of  “…In an interesting scarcity future in which we follow the fate of a character abandoned by her mother, water itself becomes a character. In the second paragraph we’re told that “Water is a shape shifter,” and in the next page we encounter the following description: “Water was paradox. Aggressive yet yielding. Life-giving yet dangerous. Floods. Droughts. Mudslides. Tsunamis. Water cut recursive patterns of creative destruction through the landscape, an ouroboros remembering.” These descriptive musings cleverly turn out to be more than metaphors and tie in directly to the tale’s surprising ending.”—Alvaro Zinos-Amaro,

“…In an interesting scarcity future in which we follow the fate of a character abandoned by her mother, water itself becomes a character. In the second paragraph we’re told that “Water is a shape shifter,” and in the next page we encounter the following description: “Water was paradox. Aggressive yet yielding. Life-giving yet dangerous. Floods. Droughts. Mudslides. Tsunamis. Water cut recursive patterns of creative destruction through the landscape, an ouroboros remembering.” These descriptive musings cleverly turn out to be more than metaphors and tie in directly to the tale’s surprising ending.”—Alvaro Zinos-Amaro,  Water Is… The Meaning of Water

Water Is… The Meaning of Water

But Joshua is a spirited creek – in spite of all it has been through, Joshua Creek is among the top two urban creeks for healthy water quality, and is still inhabited by a variety of aquatic animals like small fish and insects. Joshua Creek is home to forests, wetlands and thickets with around 150 plant species, and provides an important natural habitat corridor for the movement of birds and other animals, including migratory species. Rather than exclusively shrinking, there are also areas of Joshua Creek that are actually in the middle of regrowing their forests, and in spite of everything, Joshua still retains some beautiful gems of natural areas.”

But Joshua is a spirited creek – in spite of all it has been through, Joshua Creek is among the top two urban creeks for healthy water quality, and is still inhabited by a variety of aquatic animals like small fish and insects. Joshua Creek is home to forests, wetlands and thickets with around 150 plant species, and provides an important natural habitat corridor for the movement of birds and other animals, including migratory species. Rather than exclusively shrinking, there are also areas of Joshua Creek that are actually in the middle of regrowing their forests, and in spite of everything, Joshua still retains some beautiful gems of natural areas.”

In my writing guidebook

In my writing guidebook  Finding the perfect place(s) to write … is important to creating meaningful entries. Journal writing is a reflective activity that requires the right environment for you. The best environment is a quiet one with no interruptions and where you are alone. A reflective environment will let you relax, find a connection with yourself and your feelings. You need a place where you can relax and not worry about someone barging in or other things distracting you from your thoughts. You should also feel physically comfortable and the place should meet your time requirements.

Finding the perfect place(s) to write … is important to creating meaningful entries. Journal writing is a reflective activity that requires the right environment for you. The best environment is a quiet one with no interruptions and where you are alone. A reflective environment will let you relax, find a connection with yourself and your feelings. You need a place where you can relax and not worry about someone barging in or other things distracting you from your thoughts. You should also feel physically comfortable and the place should meet your time requirements.

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the  Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions. Nina Munteanu’s “The Way of Water” and the anthology in which it appears was recently praised by Emilie Moorhouse in Prism International Magazine, in a review entitled

Nina Munteanu’s “The Way of Water” and the anthology in which it appears was recently praised by Emilie Moorhouse in Prism International Magazine, in a review entitled  “The Way of Water” (La natura dell’acqua) was translated by Fiorella Smoscatello for Mincione Edizioni. Simone Casavecchia of SoloLibri.net, describes “The Way of Water” in her review of the Italian version:

“The Way of Water” (La natura dell’acqua) was translated by Fiorella Smoscatello for Mincione Edizioni. Simone Casavecchia of SoloLibri.net, describes “The Way of Water” in her review of the Italian version:

“The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s

“The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

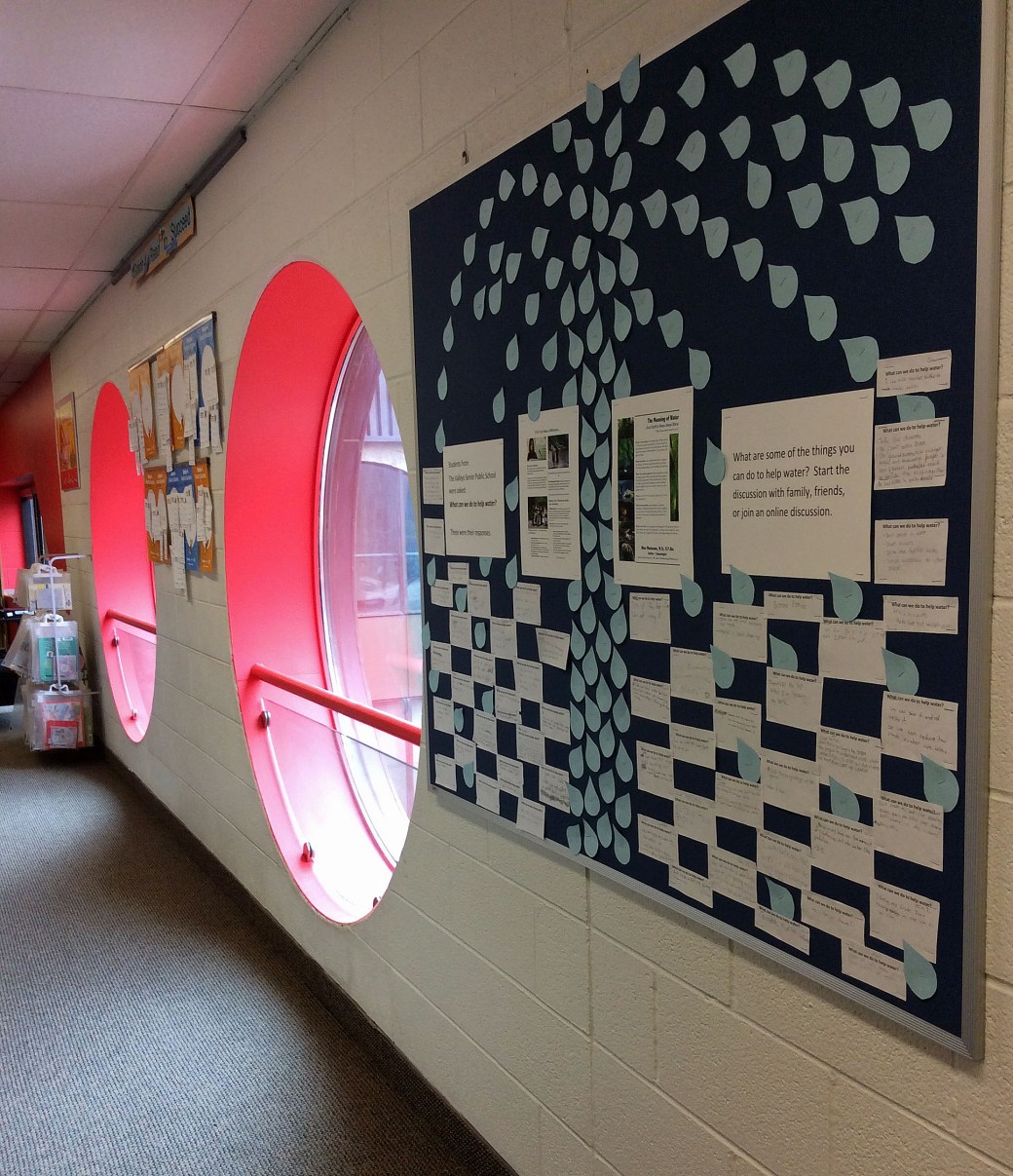

I started the talk by explaining that I’m a limnologist—someone who studies freshwater—and that water is still a mysterious substance, even for those who make it their profession to study. After informing them of water’s ubiquity in the universe—it’s virtually everywhere from quasars to planets in our solar system—I reminded them that the water that dinosaurs drank during the Paleozoic Era is the same water that you and I are drinking.

I started the talk by explaining that I’m a limnologist—someone who studies freshwater—and that water is still a mysterious substance, even for those who make it their profession to study. After informing them of water’s ubiquity in the universe—it’s virtually everywhere from quasars to planets in our solar system—I reminded them that the water that dinosaurs drank during the Paleozoic Era is the same water that you and I are drinking.

You can read so much more about water in my book

You can read so much more about water in my book  I was born on this day, some sixty+ years ago, in the small town of Granby in the Eastern Townships to German-Romanian parents. Besides its zoo—which my brother, sister and I used to visit to collect bottles for a finder’s fee at the local treat shop—the town had no particular features. It typified French-Canada of that era.

I was born on this day, some sixty+ years ago, in the small town of Granby in the Eastern Townships to German-Romanian parents. Besides its zoo—which my brother, sister and I used to visit to collect bottles for a finder’s fee at the local treat shop—the town had no particular features. It typified French-Canada of that era.

As efforts are made to reconcile the previous wrongs to Indigenous peoples within Canada and as empowering stories about environment are created and shared, Canada carries on the open and welcoming nature of our Indigenous peoples in encouraging immigration. In 2016, the same year the American government announced a ban on refugees, Canada took in 300,000 immigrants, which included 48,000 refuges. Canada encourages citizenship and around 85% of permanent residents typically become citizens. Greater Toronto is currently the most diverse city in the world; half of its residents were born outside the country. Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Montreal are not far behind.

As efforts are made to reconcile the previous wrongs to Indigenous peoples within Canada and as empowering stories about environment are created and shared, Canada carries on the open and welcoming nature of our Indigenous peoples in encouraging immigration. In 2016, the same year the American government announced a ban on refugees, Canada took in 300,000 immigrants, which included 48,000 refuges. Canada encourages citizenship and around 85% of permanent residents typically become citizens. Greater Toronto is currently the most diverse city in the world; half of its residents were born outside the country. Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Montreal are not far behind. Writer and essayist Ralston Saul suggests that Canada has taken to heart the Indigenous concept of ‘welcome’ to provide, “Space for multiple identities and multiple loyalties…[based on] an idea of belonging which is comfortable with contradictions.” Of this Forman writes:

Writer and essayist Ralston Saul suggests that Canada has taken to heart the Indigenous concept of ‘welcome’ to provide, “Space for multiple identities and multiple loyalties…[based on] an idea of belonging which is comfortable with contradictions.” Of this Forman writes: And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.” Canada is a true multi-cultural nation that celebrates its diversity: the wholes that make up the wholes.

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.” Canada is a true multi-cultural nation that celebrates its diversity: the wholes that make up the wholes. So, am I still proud of Canada? Definitely. We have much to be proud of. We live in one of the wealthiest countries in the world and the 8th highest ranking in the Human Development Index. Canada ranks among the highest in international measurements of government transparency, civil liberties, quality of life, economic freedom, and education. It stands among the world’s most educated countries—ranking first worldwide in the number of adults having tertiary education with 51% of adults holding at least an undergraduate college or university degree. With two official languages, Canada practices an open cultural pluralism toward creating a cultural mosaic of racial, religious and cultural practices. Canada’s symbols are influenced by natural, historical and Aboriginal sources. Prominent symbols include the maple leaf, the beaver, Canada Goose, Common Loon, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the polar bear, the totem pole, and Inuksuk.

So, am I still proud of Canada? Definitely. We have much to be proud of. We live in one of the wealthiest countries in the world and the 8th highest ranking in the Human Development Index. Canada ranks among the highest in international measurements of government transparency, civil liberties, quality of life, economic freedom, and education. It stands among the world’s most educated countries—ranking first worldwide in the number of adults having tertiary education with 51% of adults holding at least an undergraduate college or university degree. With two official languages, Canada practices an open cultural pluralism toward creating a cultural mosaic of racial, religious and cultural practices. Canada’s symbols are influenced by natural, historical and Aboriginal sources. Prominent symbols include the maple leaf, the beaver, Canada Goose, Common Loon, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the polar bear, the totem pole, and Inuksuk. We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness— Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  Nina Munteanu’s near-future speculative short story “The Way of Water” in Bruce Meyer’s (editor) “Cli Fi: Canadian Tales of Climate Change”, published by

Nina Munteanu’s near-future speculative short story “The Way of Water” in Bruce Meyer’s (editor) “Cli Fi: Canadian Tales of Climate Change”, published by  A bilingual print book by

A bilingual print book by  ” ‘The Way of Water’ is to be ‘a shapeshifter,’ says Nina Munteanu in her dystopian narrative, where she draws a dark scenario and, unfortunately, not too improbable in the near future. In the universe of the story water has become a very precious commodity: rationed consumption, credits (always of water) accounted for and debts collected…The Chinese multinationals have exchanged the public debt of other states with their water reserves with which, now, they can control the climate, deciding when and where it will rain. Who understands this dirty game has been silenced, like Hilda’s mother, a limnologist, inexplicably arrested and never returned; like the daughter of two water vendors, mysteriously disappeared, after having decided not to bow to economic powers: Hanna, who now prefers secure virtual identities to evanescent real appearances. Water. The two, like the covalent bond of a complex molecule, develop a relationship of attraction and repulsion that will first make them meet and then, little by little, will change into a tormented love but, at the same time, so pure as to cause Hilda at great risk, to make an extreme decision that will allow Hanna to realize the strange prophecy that the internal voice, perhaps the consciousness of water, had resonated in the two women for a long time.

” ‘The Way of Water’ is to be ‘a shapeshifter,’ says Nina Munteanu in her dystopian narrative, where she draws a dark scenario and, unfortunately, not too improbable in the near future. In the universe of the story water has become a very precious commodity: rationed consumption, credits (always of water) accounted for and debts collected…The Chinese multinationals have exchanged the public debt of other states with their water reserves with which, now, they can control the climate, deciding when and where it will rain. Who understands this dirty game has been silenced, like Hilda’s mother, a limnologist, inexplicably arrested and never returned; like the daughter of two water vendors, mysteriously disappeared, after having decided not to bow to economic powers: Hanna, who now prefers secure virtual identities to evanescent real appearances. Water. The two, like the covalent bond of a complex molecule, develop a relationship of attraction and repulsion that will first make them meet and then, little by little, will change into a tormented love but, at the same time, so pure as to cause Hilda at great risk, to make an extreme decision that will allow Hanna to realize the strange prophecy that the internal voice, perhaps the consciousness of water, had resonated in the two women for a long time. “The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s

“The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s

After she and fellow colonists crash land on the hostile jungle planet of Mega, rebel-scientist Izumi, widower and hermit, boldly sets out against orders on a hunch that may ultimately save her fellow survivors—but may also risk all. As the other colonists take stock, Izumi—obsessed with discovery and the need to save lives—plunges into the dangerous forest, which harbors answers, not only to their freshwater problem, but ultimately to the nature of the universe itself. Mega was a goldilocks planet—it had saltwater and supported life—but the planet also possessed magnetic-electro-gravitational anomalies and a gravitational field that didn’t match its size and mass. The synchronous dance of its global electromagnetic field suggested self-organization to Izumi, who slowly pieced together Mega’s secrets: from its “honeycomb” pools to the six-legged uber-predators and jungle infrasounds—somehow all connected to the water. Still haunted by the meaningless death of her family back on Mars, Izumi’s intrepid search for life becomes a metaphoric and existential journey of the heart that explores how we connect and communicate—with one another and the universe—a journey intimately connected with water.

After she and fellow colonists crash land on the hostile jungle planet of Mega, rebel-scientist Izumi, widower and hermit, boldly sets out against orders on a hunch that may ultimately save her fellow survivors—but may also risk all. As the other colonists take stock, Izumi—obsessed with discovery and the need to save lives—plunges into the dangerous forest, which harbors answers, not only to their freshwater problem, but ultimately to the nature of the universe itself. Mega was a goldilocks planet—it had saltwater and supported life—but the planet also possessed magnetic-electro-gravitational anomalies and a gravitational field that didn’t match its size and mass. The synchronous dance of its global electromagnetic field suggested self-organization to Izumi, who slowly pieced together Mega’s secrets: from its “honeycomb” pools to the six-legged uber-predators and jungle infrasounds—somehow all connected to the water. Still haunted by the meaningless death of her family back on Mars, Izumi’s intrepid search for life becomes a metaphoric and existential journey of the heart that explores how we connect and communicate—with one another and the universe—a journey intimately connected with water. Fingal’s Cave

Fingal’s Cave Fingal’s Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The cave is formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns in a Paleocene lava flow (similar to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland). Its entrance is a large archway filled by the sea. The eerie sounds made by the echoes of waves in the cave, give it the atmosphere of a natural cathedral. Known for its natural acoustics, the cave is named after the hero of an epic poem by 18th century Scots poet-historian James Macpherson. Fingal means “white stranger”.

Fingal’s Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The cave is formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns in a Paleocene lava flow (similar to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland). Its entrance is a large archway filled by the sea. The eerie sounds made by the echoes of waves in the cave, give it the atmosphere of a natural cathedral. Known for its natural acoustics, the cave is named after the hero of an epic poem by 18th century Scots poet-historian James Macpherson. Fingal means “white stranger”.