“Canada is the only country in the world that knows how to live without an identity.”—Marshal McLuhan

Nina “reading” in Granby, Quebec

I was born some sixty+ years ago, in the small town of Granby in the Eastern Townships to German-Romanian parents. Besides its zoo—which my brother, sister and I used to visit to collect bottles for a finder’s fee at the local treat shop—the town had no particular features. It typified French-Canada of that era. So did I. I went to school in Quebec then migrated across to the west coast to practice and teach limnology. Given that Canada holds at any one time a fifth of the Earth’s freshwater, that also made sense.

Canada is a vast country with a climate and environment that spans from the boreal forests of the Canadian Shield, muskegs of northern BC, and tundras of the Arctic Circle to the grasslands of the Prairies and southern woodlands of Ontario and Quebec. Canada’s environment is vast and diverse. Like its people.

Ecologist vs Nationalist

Ecology is the study of “home” (oikos means ‘home’ in Greek). Ecology studies the relationships that make one’s home functional. It is, in my opinion, the most holistic and natural way to assess where we live. My home is currently Toronto, Ontario, Canada and ultimately the planet Earth.

The Eastern Townships in autumn are a cornucopia of festive colours.

Growing up in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, I’d always felt an abiding sense of belonging and I resonated with Canada’s national symbols—mostly based on Nature and found on our currency, our flag, and various sovereign images: the loon, the beaver, the maple tree, our mountains and lakes and boreal forests. Why not? Canadians are custodians of a quarter of the world’s wetlands, longest river systems and most expansive lakes. Most of us recognize this; many of us live, play and work in or near these natural environments.

I have long considered myself a global citizen with no political ties. I saw my country through the lens of an ecologist—I assessed my community and my surroundings in terms of ecosystems that supported all life, not just humanity. Was a community looking after its trees? Was my family recycling? Was a corporation using ‘green’ technology? Was a municipality daylighting its streams and recognizing important riparian zones? I joined environmental movements when I was a teenager. I shifted my studies from art to science because I wanted to make a difference in how we treated our environment. After university, I joined an environmental consulting firm, hoping to educate corporations and individuals as environmental stewards. I brought that philosophy into a teaching career and began writing eco-fiction, science fiction and essays to help promote an awareness and a connection with our natural world. My hope was to illuminate how important Nature and water is to our planet and to our own well-being through an understanding of ecology and how everything is interconnected.

Nina kayaking Desolation Sound in British Columbia

When I think of Canada, I think of my “home”, where I live; my community and my environment. I have traveled the world and I feel a strong sense of “home” and belonging every time I return. Canada is my home. I was born and grew up in Quebec. I lived in British Columbia, Ontario, and Nova Scotia; each of these places engendered a feeling of “home”.

The Dory Shop in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

I think that part of being a Canadian is related to this sense of belonging (and pride) in a country that is not tied to some core political identity or melting-pot mainstream.

Historian and writer Charlotte Gray wrote:

“we live in a country that has a weak national culture and strong regional identities …Two brands of psychological glue bind Canada together: political culture and love of landscape…[in] a loose federation perched on a magnificent and inhospitable landscape—[we are] a nation that sees survival as a collective enterprise.”—Charlotte Gray

Marsh near Barkerville, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Canada as Postnational State

In October 2015, Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told the New York Times that Canada may be the “first postnational state,” adding that “there is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada.” This is largely because Canadians, writes Charles Forman in the Guardian, are “philosophically predisposed to an openness that others find bewildering, even reckless.”

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

We are who we are because of what we are: a vast country the size of Europe. A country dominated by boreal forest, a vital and diverse wilderness that helps maintain the well-being of our entire planet. A land that encompasses over a fifth of the freshwater in the world, and a quarter of the world’s wetlands. Canadians are ultimately the world’s Natural stewards. That is who and what we are.

Eramosa River, Ontario (photo by Nina Munteanu)

According to Forman, postnationalism frames how “to understand our ongoing experiment in filling a vast yet unified geographic space with the diversity of the world” and a “half-century old intellectual project, born of the country’s awakening from colonial slumber.” As the first Europeans arrived in North America, the Indigenous people welcomed them, taught them how to survive and thrive amid multiple identities and allegiances, writes Forman. “That welcome was often betrayed, particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries, when settlers did profound harm to Indigenous people.” But, says Forman, if the imbalance remains, so does the influence: a model of another way of belonging. One I think many Canadians are embracing. We are learning from the natural wisdom of our Indigenous peoples. Even our fiction reflects how we value our environment and embrace diversity. “Diversity fuels, not undermines, prosperity,” writes Forman.

As efforts are made to reconcile the previous wrongs to Indigenous peoples within Canada and as empowering stories about environment are created and shared, Canada carries on the open and welcoming nature of our Indigenous peoples in encouraging immigration. In 2016, the same year the American government announced a ban on refugees, Canada took in 300,000 immigrants, which included 48,000 refuges. Canada encourages citizenship and around 85% of permanent residents typically become citizens. Greater Toronto is currently the most diverse city in the world; half of its residents were born outside the country. Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Montreal are not far behind.

Mom and son explore BC wilderness

Canadian author and visionary Marshal McLuhan wrote in 1963 that, “Canada is the only country in the world that knows how to live without an identity.” This is an incredible accomplishment, particularly given our own colonial history and the current jingoistic influence of the behemoth south of us.

Writer and essayist Ralston Saul suggests that Canada has taken to heart the Indigenous concept of ‘welcome’ to provide,

“Space for multiple identities and multiple loyalties…[based on] an idea of belonging which is comfortable with contradictions.”

Of this Forman writes: “According to poet and scholar BW Powe, McLuhan saw in Canada the raw materials for a dynamic new conception of nationhood, one unshackled from the state’s ‘demarcated borderlines and walls, its connection to blood and soil,’ its obsession with ‘cohesion based on a melting pot, on nativist fervor, the idea of the promised land’. Instead, the weakness of the established Canadian identity encouraged a plurality of them—not to mention a healthy flexibility and receptivity to change. Once Canada moved away from privileging denizens of the former empire to practicing multiculturalism, it could become a place where ‘many faiths and histories and visions would co-exist.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

Canada is a true multi-cultural nation that celebrates its diversity: the wholes that make up the wholes.

Confident and comfortable with our ‘incomplete identity’—recognizing it for what it is—is according to Forman, “a positive, a spur to move forward without spilling blood, to keep thinking and evolving—perhaps, in the end, simply to respond to newness without fear.”

This resonates with me as an ecologist. What I envision is a Canada transcending the political to embrace the environment that both defines us and provides us with our very lives; a view that knows no boundaries, and recognizes the importance of diversity, relationship and inclusion, interaction, movement, and discovery.

So, am I proud of Canada? Definitely. We have much to be proud of. Canada is the 8th highest ranking nation in the Human Development Index. Canada ranks among the highest in international measurements of government transparency, civil liberties, quality of life, economic freedom, and education. It stands among the world’s most educated countries—ranking first worldwide in the number of adults having tertiary education with 51% of adults holding at least an undergraduate college or university degree. With two official languages, Canada practices an open cultural pluralism toward creating a cultural mosaic of racial, religious and cultural practices. Canada’s symbols are influenced by natural, historical and Aboriginal sources. Prominent symbols include the maple leaf, the beaver, Canada Goose, Common Loon, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the polar bear, the totem pole, and Inuksuk.

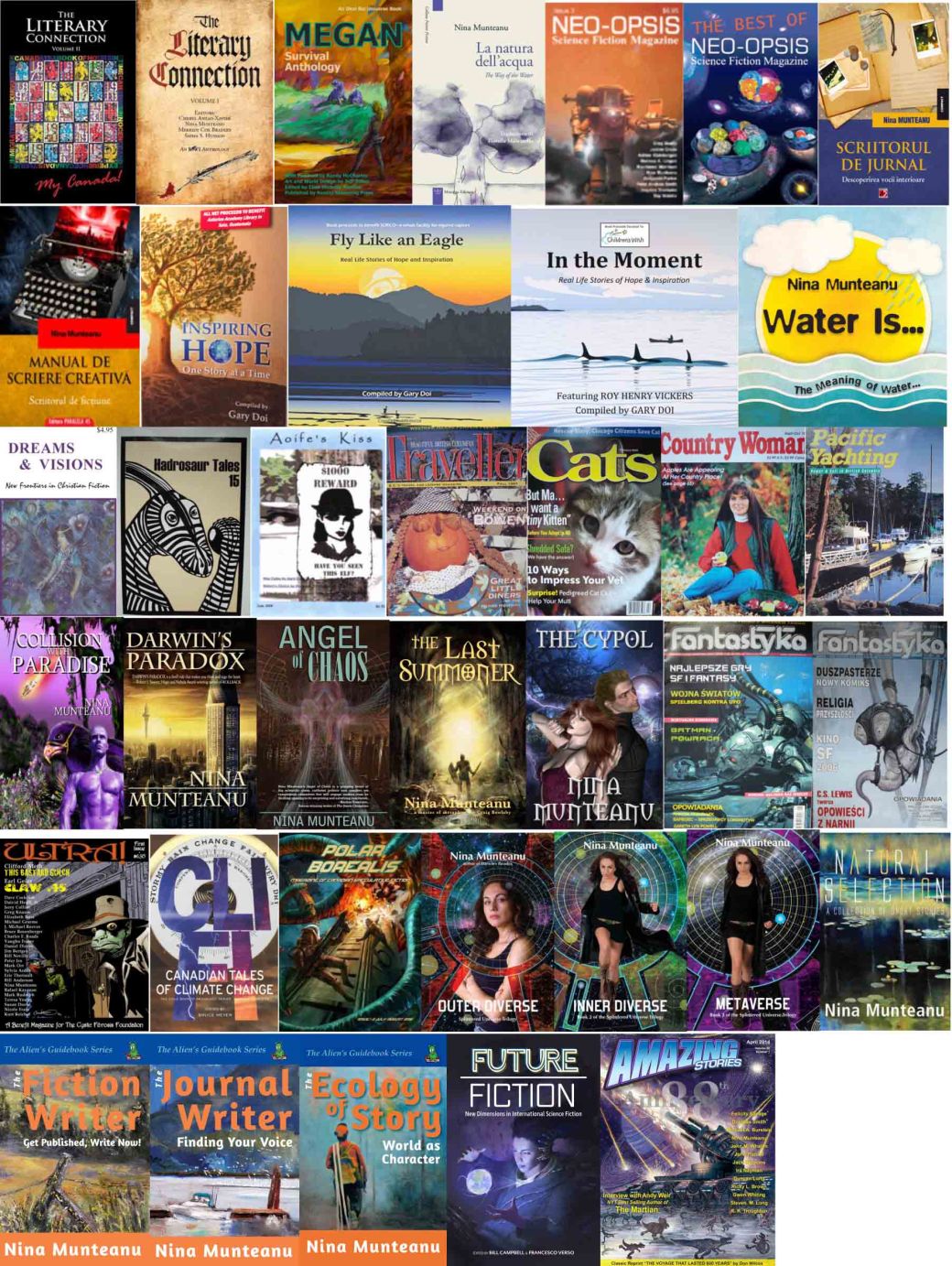

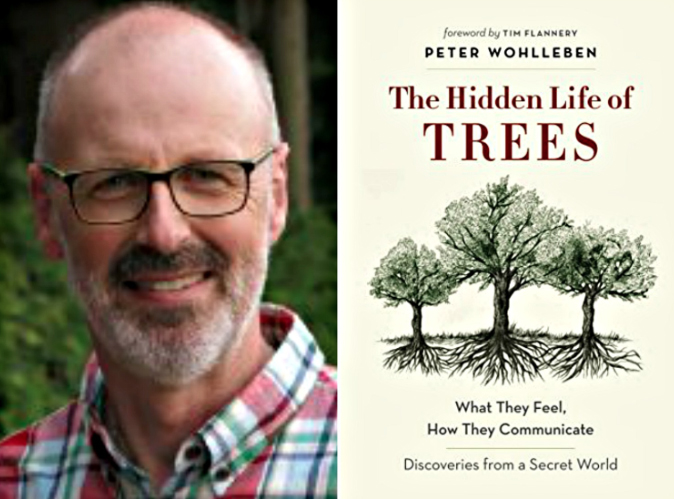

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—particularly of climate change—is more and more being reflected in our literature—from Margaret Atwood’s “Maddaddam” trilogy and Kim Stanley Robinson’s “2041” to my short story collection “Natural Selection” and non-fiction book “Water Is…” .

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—particularly of climate change—is more and more being reflected in our literature—from Margaret Atwood’s “Maddaddam” trilogy and Kim Stanley Robinson’s “2041” to my short story collection “Natural Selection” and non-fiction book “Water Is…” .

Canadians are writing more eco-fiction, climate fiction, and fiction in which environment somehow plays a key role.

Canadians are writing more eco-fiction, climate fiction, and fiction in which environment somehow plays a key role.

Water has become one of those key players: I recently was editor of the Reality Skimming Press anthology “Water”, a collection of six speculative Canadian stories that optimistically explore near-future scenarios with water as principle agent.

My short story “The Way of Water” is a near-future vision of Canada that explores the nuances of corporate and government corruption and deceit together with resource warfare.

My short story “The Way of Water” is a near-future vision of Canada that explores the nuances of corporate and government corruption and deceit together with resource warfare.

First published as a bilingual print book by Mincione Edizioni (Rome) (“La natura dell’acqua”), the short story also appears in several anthologies including Exile Editions “Cli Fi: Canadian Tales of Climate Change” and “Future Fiction: New Dimensions in International Science Fiction“. My upcoming “A Diary in the Age of Water” continues the story.

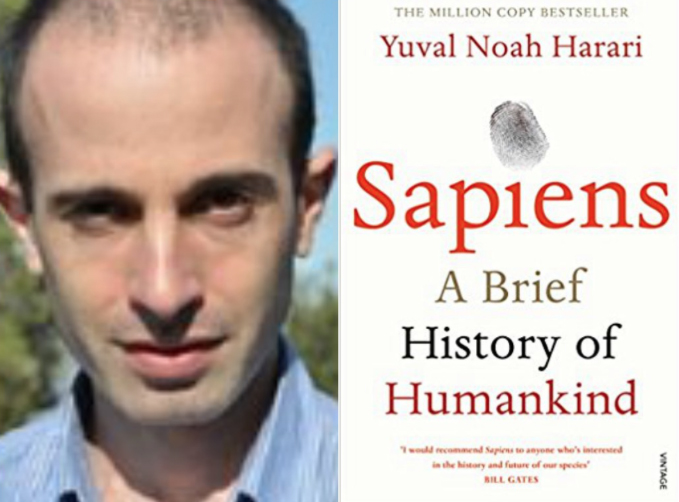

Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “Water Entanglement“, which also addresses a near-future Canada premise in which water plays a major role.

Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “Water Entanglement“, which also addresses a near-future Canada premise in which water plays a major role.

In a recent interview with Mary Woodbury on Eco-Fiction, I reflected on a trend over the years that I noticed in the science fiction writing course I teach at George Brown College: “It’s a workshop-style course I teach and students are encouraged to bring in their current work in progress. More and more students are bringing in a WIP with strong ecological overtones. I’d say the percentage now is over 70%. This is definitely coming from the students—it’s before I even open my mouth about ecology and eco-fiction—and what it suggests to me is that the welfare of our planet and our ecosystems is on many people’s minds and this is coming through in our most metaphoric writing: science fiction.”

It is healthy to celebrate our accomplishments while remembering where we came from and what we still need to accomplish. This provides direction and motivation.

Deer Lake, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Canadians are custodians of a quarter of the world’s wetlands, longest river systems and most expansive lakes. Canada is all about water… And so are we.

We are water; what we do to water we do to ourselves.

Happy Canada Day!

References:

Dechene, Paul. 2015. “Sci-Fi Writers Discuss Climate Catastrophe: Nina Munteanu, Author of Darwin’s Paradox.” Prairie Dog, December 11, 2015.

Forman, Charles. 2017. “The Canada Experiment: Is this the World’s First Postnational Country?” The Guardian, January 4, 2017.

Gray, Charlotte. 2017. “Heroes and Symbols” The Globe and Mail.

Moorhouse, Emilie. 2018. “New ‘cli-fi’ anthology brings Canadian visions of future climate crisis.” National Observer, March 9, 2018.

Munteanu, Nina. 2016. “Crossing into the Ecotone to Write Meaningful Eco-Fiction.” In: NinaMunteanu.me, December 18, 2016.

Newman-Stille, Derek. 2017. “The Climate Around Eco-Fiction.” In: Speculating Canada, May 24, 2017.

Woodbury, Mary. 2016. “Part XV. Women Working in Nature and the Arts: Interview with Nina Munteanu, Ecologist and Author.” Eco-Fiction.com, October 31, 2016.

Nina Munteanu on the Credit River, Ontario (photo by Merridy Cox)

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

In an article I’d written some time ago on my blog The Alien Next Door (“Fertility — Infertility & the Environment”, with commentary on the film “Children of Men”) I got into a rather lively discussion with a fellow blogger (Erik) about the tendency in Western Culture mythos (in literature and in movies, particularly) to portray the main character in fiction as Christ figure and the ramifications of this choice. Erik lamented the separation that has occurred between “Jesus the Teacher” and “Christ the Redeemer”. I hadn’t really given this much thought until he brought it up. But his examples (e.g., Matrix and Harry Potter) and his discourse were so compelling, I had to ponder. So, here are my ponderings.

In an article I’d written some time ago on my blog The Alien Next Door (“Fertility — Infertility & the Environment”, with commentary on the film “Children of Men”) I got into a rather lively discussion with a fellow blogger (Erik) about the tendency in Western Culture mythos (in literature and in movies, particularly) to portray the main character in fiction as Christ figure and the ramifications of this choice. Erik lamented the separation that has occurred between “Jesus the Teacher” and “Christ the Redeemer”. I hadn’t really given this much thought until he brought it up. But his examples (e.g., Matrix and Harry Potter) and his discourse were so compelling, I had to ponder. So, here are my ponderings. Today’s Christ-like hero suffers for the sins of the world and prepares himself (often struggling with this considerably) to deliver salvation, usually through fighting or violent confrontation and often with an incredible arsenal of weapons. I was swiftly brought to mind of the many action shoot-em up films whose tortured hero redeems him(her)self through some selfless, though violent action (e.g., Omega Man, V for Vendetta, Ultra Violet, Aeon Flux — all sci-fi movies, by the way, and ones I enjoyed immensely. And what about all those superhero movies, like Spiderman, X-Men, Green Lantern, etc. These films represent one version of Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey”, where the original hero leaves his ‘ordinary world’ wherein he/she has some major flaw to overcome (like apathy, greed, distrust, anger, fear of strawberries…etc.) to answer ‘the call’ to be the hero he/she was destined to become. This is a very familiar trope. Erik suggested that Western culture’s “concept of Redemption has invariably separated from the Grace that created it.” Jesus the Teacher had somehow fallen to the wayside to make room for Christ the Redeemer. According to Erik: “Jesus the Teacher said to ‘turn the other cheek’, but today’s Redeemers kick ass. Jesus the Teacher told us that what is done in love is blessed, but today’s Redeemers have more personal and interior motivations.” The two have simply become two different people, says Erik and “the latter is a superstar” compared to the former.” He ends his post with these compelling thoughts:

Today’s Christ-like hero suffers for the sins of the world and prepares himself (often struggling with this considerably) to deliver salvation, usually through fighting or violent confrontation and often with an incredible arsenal of weapons. I was swiftly brought to mind of the many action shoot-em up films whose tortured hero redeems him(her)self through some selfless, though violent action (e.g., Omega Man, V for Vendetta, Ultra Violet, Aeon Flux — all sci-fi movies, by the way, and ones I enjoyed immensely. And what about all those superhero movies, like Spiderman, X-Men, Green Lantern, etc. These films represent one version of Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey”, where the original hero leaves his ‘ordinary world’ wherein he/she has some major flaw to overcome (like apathy, greed, distrust, anger, fear of strawberries…etc.) to answer ‘the call’ to be the hero he/she was destined to become. This is a very familiar trope. Erik suggested that Western culture’s “concept of Redemption has invariably separated from the Grace that created it.” Jesus the Teacher had somehow fallen to the wayside to make room for Christ the Redeemer. According to Erik: “Jesus the Teacher said to ‘turn the other cheek’, but today’s Redeemers kick ass. Jesus the Teacher told us that what is done in love is blessed, but today’s Redeemers have more personal and interior motivations.” The two have simply become two different people, says Erik and “the latter is a superstar” compared to the former.” He ends his post with these compelling thoughts: If you still don’t get what Erik and I are talking about, go watch the poignant film Pay It Forward and then contrast its main character with the one in Ultra Violet or The Matrix.

If you still don’t get what Erik and I are talking about, go watch the poignant film Pay It Forward and then contrast its main character with the one in Ultra Violet or The Matrix. While I agree with Erik on the apparent separation of Christ figure in today’s popular fiction, perhaps there is another way to look at these tales that resolves this apparent dichotomy to some degree. My suggestion is to view them more as allegories with traits and values represented in several characters woven together in a complete and whole tapestry. To do so is to include the secondary character as being equally important. Let’s take Matrix, for instance. In fact, Neo isn’t the only Jesus-figure. His two female opposites (Trinity/Oracle) demonstrate Christ-like traits that embody grace, mercy, love (the holy spirit) and wisdom. Okay, so Trinity kicks major ass too; but her character also provides the chief motivation for our main ‘kick-ass’ hero through her selfless love and humility.

While I agree with Erik on the apparent separation of Christ figure in today’s popular fiction, perhaps there is another way to look at these tales that resolves this apparent dichotomy to some degree. My suggestion is to view them more as allegories with traits and values represented in several characters woven together in a complete and whole tapestry. To do so is to include the secondary character as being equally important. Let’s take Matrix, for instance. In fact, Neo isn’t the only Jesus-figure. His two female opposites (Trinity/Oracle) demonstrate Christ-like traits that embody grace, mercy, love (the holy spirit) and wisdom. Okay, so Trinity kicks major ass too; but her character also provides the chief motivation for our main ‘kick-ass’ hero through her selfless love and humility. Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

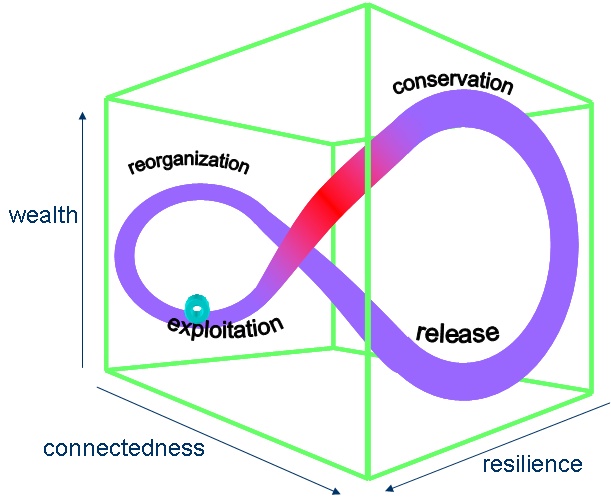

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In  In my speculative fiction novel,

In my speculative fiction novel,

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before;

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before; In my book

In my book

When Pixl Press started looking for suitable cover artists to rebrand my writing craft series, I showed some of Anne’s work to the director Anne Voute. Pixl Press had already worked with Costi Gurgu and we liked his work. The result of Anne’s illustrations and Costi’s typography and design was a series of stunning covers that branded my books with just the right voice.

When Pixl Press started looking for suitable cover artists to rebrand my writing craft series, I showed some of Anne’s work to the director Anne Voute. Pixl Press had already worked with Costi Gurgu and we liked his work. The result of Anne’s illustrations and Costi’s typography and design was a series of stunning covers that branded my books with just the right voice. The Alien Guidebook Series, of which two books are out so far (

The Alien Guidebook Series, of which two books are out so far ( Anne’s illustration for

Anne’s illustration for  I am currently researching and writing the third guidebook in the series—a reference on world building and use of ecology in story—The Ecology of Story: World as Character.

I am currently researching and writing the third guidebook in the series—a reference on world building and use of ecology in story—The Ecology of Story: World as Character.

Anne’s art work for the cover of

Anne’s art work for the cover of

In my upcoming novel “

In my upcoming novel “ In a talk I give at conferences on “

In a talk I give at conferences on “ Terms such as

Terms such as  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  I recently attended Claudiu Murgan’s signing of his science fiction book Water Entanglement at Indigo in Yorkdale Mall and had a chance to ask him some questions about the book that intrigued me.

I recently attended Claudiu Murgan’s signing of his science fiction book Water Entanglement at Indigo in Yorkdale Mall and had a chance to ask him some questions about the book that intrigued me.

“…Since the creation of Earth, water and crystals have woven their paths into a billion-year-long tapestry that has captured the cycles of nature’s evolution. They have observed the appearance of humans and their troubled, but fascinating development, and the energies and vibrations of everything that is part of this amazing eco-system . . . In 2055 water activists fight against irresponsible corporations that pillage the Earth. Hayyin, the hidden identity of Cherry Mortinger, a limnologist, leads the movement. Will she be able to prove that water has memory and is alive and that we could awaken to the possibility of facing a fierce battle against the primordial element that gave us life: WATER?”

“…Since the creation of Earth, water and crystals have woven their paths into a billion-year-long tapestry that has captured the cycles of nature’s evolution. They have observed the appearance of humans and their troubled, but fascinating development, and the energies and vibrations of everything that is part of this amazing eco-system . . . In 2055 water activists fight against irresponsible corporations that pillage the Earth. Hayyin, the hidden identity of Cherry Mortinger, a limnologist, leads the movement. Will she be able to prove that water has memory and is alive and that we could awaken to the possibility of facing a fierce battle against the primordial element that gave us life: WATER?” Claudiu Murgan was born in Romania and has called Canada his home since 1997. He started writing science fiction when he was 11 years old. Since then he met remarkable writers who helped him improve his own trade. His first novel, The Decadence of Our Souls highlights his belief in a potentially better world if the meanings of Love, Gratitude and Empathy could be understood by all of our brothers and sisters.

Claudiu Murgan was born in Romania and has called Canada his home since 1997. He started writing science fiction when he was 11 years old. Since then he met remarkable writers who helped him improve his own trade. His first novel, The Decadence of Our Souls highlights his belief in a potentially better world if the meanings of Love, Gratitude and Empathy could be understood by all of our brothers and sisters.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness— Canadians are writing more

Canadians are writing more  My short story “

My short story “ Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “

Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “