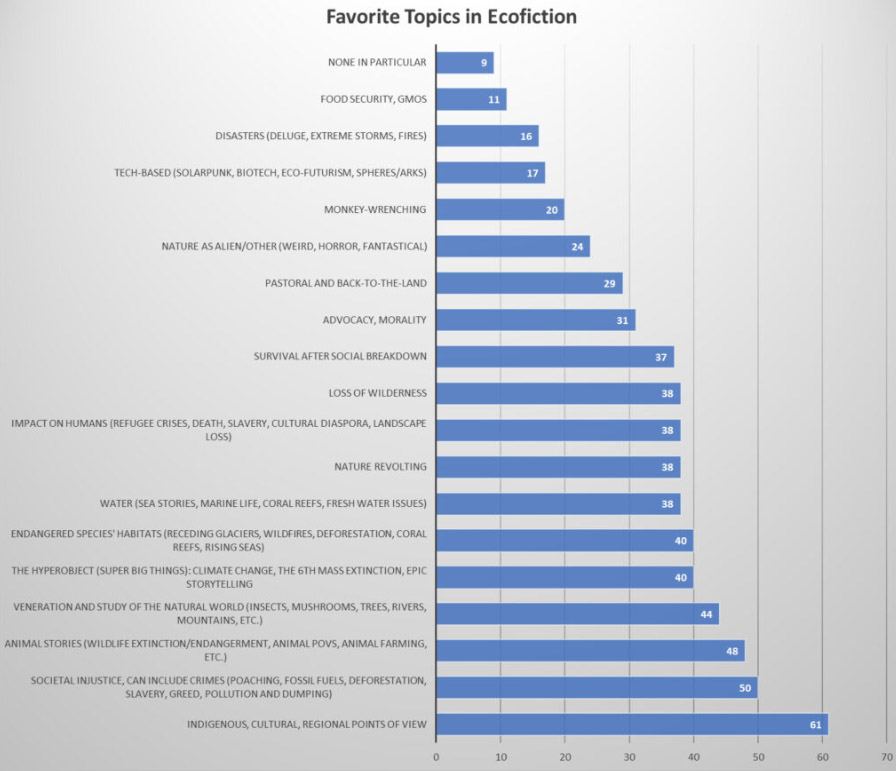

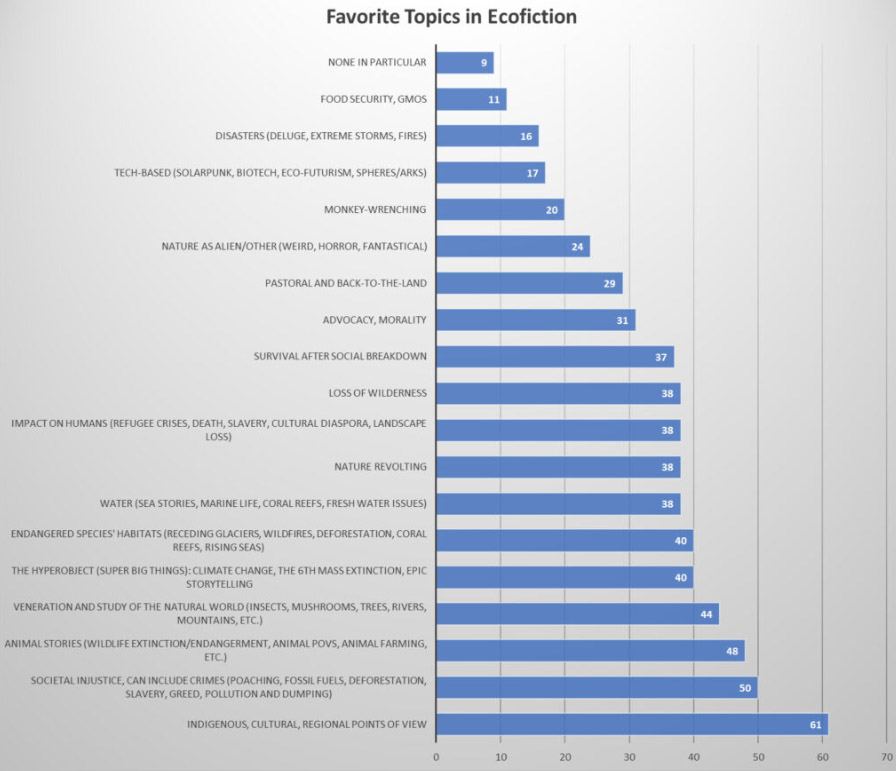

Mary Woodbury on Dragonfly.eco recently shared a survey of over a hundred readers to determine the impact that eco-fiction had on them. What did environmental fiction mean to readers? What about it appealed to them? What were their favourite works? And did it incite them to action? The answers were both expected and surprising. Given the sample size and some study limitations on audience and diversity, the results are preliminary still. However, they remain interesting and enlightening.

Some of the most impactful novels according to the readers surveyed include Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series.

Some of the most impactful novels according to the readers surveyed include Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series.

Readers gave Woodbury several reasons why they enjoyed and found eco-novels impactful:

- Realism or compelling account of or reflection of society, scary or not

- Goes beyond readers’ culture–expands minds

- Humorous

- Story focused on characters versus an issue

- Learned something new

- Opened readers’ minds

- Captured imagination

- Positive endings

- Good storytelling

- Interesting characters

- Suspense and/or psychological burn

One reader mentioned that what appealed to them about Emmi Itäranta’s Memory of Water was the style of writing. It provoked “feelings of utter beauty but also unease.”

One reader enjoyed Cormac Mccarthy’s The Road “for its spare post-apocalyptic world where even language seems to run out.”

Of Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves a reader wrote that “The dystopic beginning felt so real, and then the positive ending was so good. I loved it and it made me think about how climate change can possibly have impacts beyond just our physical and mental health, but also our dreams!”

A reader of Frank Herbert’s Dune wrote that “it was the first time I’d seen a literary rendering of an ecosystem that felt real. The ideas of ecology are woven into this story in a way I didn’t think was possible for fiction. Interconnection is hard to think about, hard to grasp, and Dune showed me that fiction, done well, can really help with this.” The same reader acknowledged that in Annihilation Jeff VenderMeer “mastered the technique.”

Graph from Environmental Fiction Impact Survey by Mary Woodbury

When asked the question “Do you think that environmental themes in fiction can impact society, and if so, how?” 81% agreed and qualified their answers:

- Fiction can encourage empathy and imagination. Stories can affect us more than dry facts. Fiction reaches us more deeply than academic understanding, moving us to action.

- Fiction can trigger a sense of wonder about the natural world, and even a sense of loss and mourning. Stories can immerse readers into imagined worlds with environmental issues similar to ours.

- Fiction raises awareness, encourages conversations and idea-sharing. Fiction is one way that helps to create a vision of our future. Cautionary tales can nudge people to action and encourage alternative futures. Novels can shift viewpoints without direct confrontation, avoid cognitive dissonance, and invite reframed human-nature relationships through enjoyment and voluntary participation.

- Environmental themes can reorient our perspective from egocentrism to the greater-than-human world.

Graph from Environmental Fiction Impact Survey by Mary Woodbury

In summary, Woodbury writes:

“The sample size (103) seems to be a good one for people who are mostly familiar with the idea of eco-fiction (and similar environmental/nature fiction genres and subgenres), though I was still hoping to get a larger, more diverse group of participants. The majority of respondents were highly educated middle-aged women. The majority of the group read from 1-29 novels a year. Favorite novels represented mostly North American or European authors (male and female about equally, with J.R.R. Tolkien, Barbara Kingsolver and Margaret Atwood consistently a favorite), with the majority of readers enjoying literary fiction the most, followed by dystopia/utopia and then science fiction.”

Woodbury notes that the genres of science fiction and fantasy were well represented in the survey, “both as favorite and most impactful novels, despite literary fiction being the favorite genre among the participants.” Of novels that respondents enjoyed, “readers were most impacted by good storytelling.” Polemic was not well regarded.

Achieving Impactful Eco-Fiction & Avoiding Polemic Through Use of Metaphor

The key to impact and enjoyment for a reader lies in good storytelling. The very best storytelling uses metaphor and oblique description to achieve a deeper meaning. The greatest art must be left to interpretation; not directly dispensed. Great art is felt and experienced viscerally; not just taken in intellectually. Great art shows; not tells.

In my writing guidebook The Ecology of Story: World as Character, I discuss the various ways that the use of metaphor achieves depth and meaning in story, particularly in eco-fiction. One impactful way is in the choice of setting. In the chapter on Place as Metaphor, I write:

In my writing guidebook The Ecology of Story: World as Character, I discuss the various ways that the use of metaphor achieves depth and meaning in story, particularly in eco-fiction. One impactful way is in the choice of setting. In the chapter on Place as Metaphor, I write:

Everything in story is metaphor, Ray Bradbury once told me. That is no more apparent than in setting and place, in which a story is embedded and through which characters move and interact.

Metaphor is the subtext that provides the subtleties in story, subtleties that evoke mood, anticipation, and memorable scenes. Richard Russo says, “to know the rhythms, the textures, the feel of a place is to know more deeply and truly its people.” When you choose your setting, remember that its primary role is to help depict theme. This is because place is destiny.

What would the book Dune be without Arrakis, the planet Dune? What would the Harry Potter books be without Hogwarts?

Metaphor provides similarity to two dissimilar things through meaning. In the metaphor “Love danced in her heart” or the simile “his love was like a slow dance”, love is equated with the joy of dance. By providing figurative rather than literal description to something, metaphor invites participation through interpretation.

When I write “John’s office was a prison,” I am efficiently and sparingly suggesting in five words—in what would normally take a paragraph—how John felt about his workplace. The reader would conjure imagery suggested by their knowledge of a prison cell: that John felt trapped, cramped, solitary, stifled, oppressed—even frightened and threatened. Metaphor relies on sub-text knowledge. This is why metaphor is so powerful and universally relevant: the reader fully participates—the reader brings in relevance through their personal knowledge and experience and this creates the memorable aspect to the scene.

Metaphor is woven into story through the use of devices and constructs such as depiction of the senses, personification, emotional connections, memories, symbols, archetypes, analogies and comparisons. Sense, and theme interweave in story to achieve layers of movement with characters on a journey. All through metaphor.

Symbols and Archetypes

In Emmi Itäranta’s Memory of Water—about a post-climate change world of sea level rise—water is a powerful archetype, whose secret tea masters guard with their lives. Water, with its life-giving properties and other strange qualities, has been used as a powerful metaphor and archetype in many stories: from vast oceans used as a powerful metaphor and archetype in many stories: from vast oceans of mystery, beauty and danger—to the relentless flow of an inland stream. Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad is one example:

Water does not resist. Water flows. When you plunge your hand into it, all you feel is a caress. Water is not a solid wall, it will not stop you. But water always goes where it wants to go, and nothing in the end can stand against it. Water is patient. Dripping water wears away a stone. Remember that, my child. Remember you are half water. If you can’t go through an obstacle, go around it. Water does.

In my short story The Way of Water (La natura dell’acqua), water’s connection with love flows throughout the story:

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.

Love flowed like water, gliding into backwaters and lagoons with ease, filling every swale and mire. Connecting, looking for home. Easing from crystal to liquid to vapour then back, water recognized its hydrophilic likeness, and its complement. Before the inevitable decoherence, remnants of the entanglement lingered like a quantum vapour, infusing everything. Hilda always knew where and when to find Hanna on Oracle, as though water inhabited the machine and told her. Water even whispered to her when her wandering friend was about to return from the dark abyss and land unannounced on her doorstep.

In a world of severe water scarcity through climate catastrophe and geopolitical oppression, the bond of these two girls—to each other through water and with water—is like the shifting covalent bond of a complex molecule, a bond that fuses a relationship of paradox linked to the paradoxical properties of water. Just as two water drops join, the two women find each other in the wasteland of intrigue. Hilda’s relationship with Hanna—as with water—is both complex and shifting according to the bonds they make and break.

Using the Senses

Readers don’t just “watch” a character in a book; they enter the character’s body and “feel”.

How do writers satisfy the readers’ need to experience the senses fully? Description, yes. But how cold is cold? What does snow really smell like? What color is that sunset? How do you describe the taste of wine to a teetotaler?

Literal description is insufficient. To have the sense sink in and linger with the reader, it should be linked to the emotions and memories of the character experiencing it. By doing this, you are achieving several things at the same time: describing the sense as the character is experiencing it—emotionally; revealing additional information on the character through his/her reaction; and creating a more compelling link for the reader’s own experience of the sense.

Senses can be explored by writers through metaphor, linking the sense to memories, using synesthesia (cross-sensory metaphor), linking the sense psychologically to an emotion or attitude, and relating that sense in a different way (e.g., describing a visual scene from the point of view of a painter or photographer—painting with light). How a sense is interpreted by your protagonist relies on her emotional state, memories associated with that sense and her attitude.

Using Personification

Environmental forces—such as weather, climate, forests, mountains, water systems—convey the mood and tone of both story and character. These environmental forces are not just part of the scenery. To a writer, they are devices used in plot, theme and premise. They may also be a compelling character, particularly in eco-fiction, climate-fiction, and speculative fiction. Dystopian fiction often explores a violent world of contrast between the affluent and vulnerable poor that often portrays the aftermath of economic and environmental collapse (e.g., Maddaddam Trilogy, The Windup Girl, Snowpiercer, Interstellar, Mad Max). In any fiction genre it is important to get the science right. Readers of fiction with strong environmental components, however, expect to learn as much from the potential reality as from the real science upon which the premise depends.

Environmental forces—such as weather, climate, forests, mountains, water systems—convey the mood and tone of both story and character. These environmental forces are not just part of the scenery. To a writer, they are devices used in plot, theme and premise. They may also be a compelling character, particularly in eco-fiction, climate-fiction, and speculative fiction. Dystopian fiction often explores a violent world of contrast between the affluent and vulnerable poor that often portrays the aftermath of economic and environmental collapse (e.g., Maddaddam Trilogy, The Windup Girl, Snowpiercer, Interstellar, Mad Max). In any fiction genre it is important to get the science right. Readers of fiction with strong environmental components, however, expect to learn as much from the potential reality as from the real science upon which the premise depends.

In Memory of Water, Emmi Itäranta personifies this life-giving substance whose very nature is tightly interwoven with her main character. As companion and harbinger, water is portrayed simultaneously as friend and enemy. As giver and taker of life.

Water is the most versatile of all elements … Water walks with the moon and embraces the earth, and it isn’t afraid to die in fire or live in air. When you step into it, it will be as close as your own skin, but if you hit it too hard, it will shatter you … Death is water’s close companion. The two cannot be separated, and neither can be separated from us, for they are what we are ultimately made of: the versatility of water, and the closeness of death. Water has no beginning and no end, but death has both. Death is both. Sometimes death travels hidden in water, and sometimes water will chase death away, but they go together always, in the world and in us.

Water is the most versatile of all elements … Water walks with the moon and embraces the earth, and it isn’t afraid to die in fire or live in air. When you step into it, it will be as close as your own skin, but if you hit it too hard, it will shatter you … Death is water’s close companion. The two cannot be separated, and neither can be separated from us, for they are what we are ultimately made of: the versatility of water, and the closeness of death. Water has no beginning and no end, but death has both. Death is both. Sometimes death travels hidden in water, and sometimes water will chase death away, but they go together always, in the world and in us.

Personification of natural things provides the reader with an image they can clearly and emotionally relate to and care about. When a point-of-view character does the describing, we get a powerful and intimate indication of their thoughts and feelings—mainly in how they connect to place (often as symbol). When this happens, place and perception entwine in powerful force.

Donald Maass writes in Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook: “The beauty of seeing a locale through a particular perspective is that the point-of-view character cannot be separated from the place. The place comes alive, as does the observer of that place, in ways that would not be possible if described using objective point of view.” The POV character’s relationship to place helps identify the transformative elements of their journey. Such transformation is the theme of the story and ultimately portrays the story’s heart and soul.

Connecting Character with Environment

Strong relationships and linkages can be forged in story between a major character and an aspect of their environment (e.g., home/place, animal/pet, minor character as avatar/spokesperson for environment [e.g. often indigenous people]). In these examples the environmental aspect serves as symbol and metaphoric connection to theme. They can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Gone With the Wind; the sacred white pine forests for the Mi’kmaq in Barkskins; The dear animals for Beatrix Potter of the Susan Wittig Albert series.

The immense sandworms of Frank Herbert’s Dune are strong archetypes of Nature—large and graceful creatures whose movements in the vast desert sands resemble the elegant whales of our oceans:

It came from their right with an uncaring majesty that could not be ignored. A twisting burrow-mound of sand cut through the dunes within their field of vision. The mound lifted in front, dusting away like a bow wave in water.

Misunderstood, except by the indigenous Fremen, the giant sandworms are targeted as a dangerous nuisance by the colonists—when, in fact, they are closely tied to the ecological cycles of the desert planet through water and spice.

Annie Proulx opens her novel Barkskins with a scene in which René Sel and fellow barkskins (woodcutters) arrive from France in the late seventeenth century to the still pristine wilderness of Canada to settle, trade and accumulate wealth:

Annie Proulx opens her novel Barkskins with a scene in which René Sel and fellow barkskins (woodcutters) arrive from France in the late seventeenth century to the still pristine wilderness of Canada to settle, trade and accumulate wealth:

In twilight they passed bloody Tadoossac, Kébec and Trois-Rivières and near dawn moored at a remote riverbank settlement … Mosquitoes covered their hands and necks like fur. A man with yellow eyebrows pointed them at a rain-dark house. Mud, rain, biting insects and the odor of willows made the first impression of New France. The second impression was of dark vast forest, inimical wilderness.

These bleak impressions of a harsh environment crawling with pests such as bébites and moustiques underlie the combative mindset of the settlers to conquer and seize what they can of a presumed infinite resource. By page seventeen, we know that mindset well. René asks why they must cut so much forest when it would be easier to use the many adequate clearings to build their houses and settlements. Trépagny fulminates: “Easier? Yes, easier, but we are here to clear the forest, to subdue this evil wilderness.” He further explains the concept of property ownership that is based on strips of surveyable land parcels—an application of the enclosure system. For them, the vast Canadian boreal forest was never-ending and for the taking: “It is the forest of the world. It is infinite. It twists around as a snake. swallows its own tail and has no end and no beginning,” Trépagny claims.

Leaf litter in Ontario forest (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Annie Proulx’s Barkskins chronicles two immigrants who arrive in Canada in 1693 (René Sel and Charles Duquet) and their descendants over 300 years of deforestation of North America; a saga that starts with the arrival of the Europeans in pristine forest and ends with a largely decimated forest under the veil of global warming. “Barkskins” (woodcutters) are, in fact indentured servants who were brought from the Paris slums to the wilds of New France to clear the land, build and settle. Sel is forced to marry a native woman and their descendants live trapped between two cultures; Duquet runs away to become a fur trader and builds a timber empire.

The Mi’kmaq are interwoven with the land and the forest. Missionary Pere Crème, who studies language makes this observation of the natives and the forest:

He saw they were so tightly knitted into the natural world that their language could only reflect the union and that neither could be separated from the other. They seemed to believe they had grown from this place as trees grow from the soil, as new stones emerge aboveground in spring. He thought the central word for this tenet, weji-sqalia’timk, deserved an entire dictionary to itself.

The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect for anything indigenous and a fierce hunger for “more” of the forests and lands. Ensnared by settler greed, the Mi’kmaq lose their own culture and their links to the natural world erode with grave consequence. In a pivotal scene, Noë, a Mi’kmaw descendent of René Sel, grows enraged when she sees a telltale change in her brothers:

The offshore wind had shifted slightly but carried the fading clatter of boots on rock. They were wearing boots instead of moccasins. Noë knew what that meant but denied it … The men should be setting out to hunt moose, but because of the boots she knew they were going to work for the French logger.

Other Articles on Environmental Fiction, Eco-Fiction and Climate Fiction

Can Dystopian Eco-Fiction Save the Planet?

Science Fiction on Water Justice & Climate Change

Windup Girl: When Monsanto Gets Its Way

Eco-Artist Roundtable with Frank Horvat on Green Majority Radio

Thanks to Mary Woodbury for the permission to share her survey results here. Much of the second part of this article is excerpted from the “Story” section of The Ecology of Story: World as Character.

Grape leaves on fence in Toronto, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Some of the most impactful novels according to the readers surveyed include Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series.

Some of the most impactful novels according to the readers surveyed include Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series.

In my writing guidebook

In my writing guidebook  They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.  Environmental forces—such as weather, climate, forests, mountains, water systems—convey the mood and tone of both story and character. These environmental forces are not just part of the scenery. To a writer, they are devices used in plot, theme and premise. They may also be a compelling character, particularly in eco-fiction, climate-fiction, and speculative fiction. Dystopian fiction often explores a violent world of contrast between the affluent and vulnerable poor that often portrays the aftermath of economic and environmental collapse (e.g., Maddaddam Trilogy, The Windup Girl, Snowpiercer, Interstellar, Mad Max). In any fiction genre it is important to get the science right. Readers of fiction with strong environmental components, however, expect to learn as much from the potential reality as from the real science upon which the premise depends.

Environmental forces—such as weather, climate, forests, mountains, water systems—convey the mood and tone of both story and character. These environmental forces are not just part of the scenery. To a writer, they are devices used in plot, theme and premise. They may also be a compelling character, particularly in eco-fiction, climate-fiction, and speculative fiction. Dystopian fiction often explores a violent world of contrast between the affluent and vulnerable poor that often portrays the aftermath of economic and environmental collapse (e.g., Maddaddam Trilogy, The Windup Girl, Snowpiercer, Interstellar, Mad Max). In any fiction genre it is important to get the science right. Readers of fiction with strong environmental components, however, expect to learn as much from the potential reality as from the real science upon which the premise depends. Water is the most versatile of all elements … Water walks with the moon and embraces the earth, and it isn’t afraid to die in fire or live in air. When you step into it, it will be as close as your own skin, but if you hit it too hard, it will shatter you … Death is water’s close companion. The two cannot be separated, and neither can be separated from us, for they are what we are ultimately made of: the versatility of water, and the closeness of death. Water has no beginning and no end, but death has both. Death is both. Sometimes death travels hidden in water, and sometimes water will chase death away, but they go together always, in the world and in us.

Water is the most versatile of all elements … Water walks with the moon and embraces the earth, and it isn’t afraid to die in fire or live in air. When you step into it, it will be as close as your own skin, but if you hit it too hard, it will shatter you … Death is water’s close companion. The two cannot be separated, and neither can be separated from us, for they are what we are ultimately made of: the versatility of water, and the closeness of death. Water has no beginning and no end, but death has both. Death is both. Sometimes death travels hidden in water, and sometimes water will chase death away, but they go together always, in the world and in us.  Annie Proulx opens her novel Barkskins with a scene in which René Sel and fellow barkskins (woodcutters) arrive from France in the late seventeenth century to the still pristine wilderness of Canada to settle, trade and accumulate wealth:

Annie Proulx opens her novel Barkskins with a scene in which René Sel and fellow barkskins (woodcutters) arrive from France in the late seventeenth century to the still pristine wilderness of Canada to settle, trade and accumulate wealth:

Journalist, urbanist and futurist Greg Lindsay gave a rousing keynote speech to start the conference. Greg spoke about the future of cities, technology, and mobility. He is the director of applied research at NewCities and director of strategy at its mobility offshoot CoMotion. He also co-authored the international bestseller

Journalist, urbanist and futurist Greg Lindsay gave a rousing keynote speech to start the conference. Greg spoke about the future of cities, technology, and mobility. He is the director of applied research at NewCities and director of strategy at its mobility offshoot CoMotion. He also co-authored the international bestseller

We then discussed future implications of water scarcity (and geopolitical conflict) and some of the things individuals and communities can do. Much of the talk drew from my recent book

We then discussed future implications of water scarcity (and geopolitical conflict) and some of the things individuals and communities can do. Much of the talk drew from my recent book

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

I talked about the importance of theme to help determine a story’s beginning and ending. We also discussed the use of theme in memoir to help focus the memoir into a meaningful story with a directed narrative. I discussed the use of the hero’s journey plot approach and its associated archetypes to help determine relevance of events, characters and place: all topics explored in my

I talked about the importance of theme to help determine a story’s beginning and ending. We also discussed the use of theme in memoir to help focus the memoir into a meaningful story with a directed narrative. I discussed the use of the hero’s journey plot approach and its associated archetypes to help determine relevance of events, characters and place: all topics explored in my  While everyone left at six, I stayed on with a friend. I’d booked the night and looked forward to a restful evening among deer, rustling trees and a chorus of birdsong. The owner had left us some leftovers for supper, and, as we dined on a smorgasbord of gourmet food and wine, I reveled in Nature’s meditative sounds. The night sky opened deep and clear with a million stars.

While everyone left at six, I stayed on with a friend. I’d booked the night and looked forward to a restful evening among deer, rustling trees and a chorus of birdsong. The owner had left us some leftovers for supper, and, as we dined on a smorgasbord of gourmet food and wine, I reveled in Nature’s meditative sounds. The night sky opened deep and clear with a million stars.

“I was fascinated by Nina’s clear and extremely interesting lecture on the hero’s journey. Maybe all writer’s have a novel in their heads they want to write one day, and the techniques Nina shared with us will help me when I get to that point. In fact, because of her, I may get there a lot sooner than I had planned.”— Zoe M. Hicks, Saint Simon’s Island, GA

“I was fascinated by Nina’s clear and extremely interesting lecture on the hero’s journey. Maybe all writer’s have a novel in their heads they want to write one day, and the techniques Nina shared with us will help me when I get to that point. In fact, because of her, I may get there a lot sooner than I had planned.”— Zoe M. Hicks, Saint Simon’s Island, GA “The Fiction Writer is at the top of the required reading list for my Writer’s Workshop students. With its engagingly direct, conversational style and easily accessible format, it is a veritable cornucopia of hands-on help for aspiring writers of any age…the quintessential guidebook for the soon-to-be-published.”—Susan McLemore, Writing Instructor

“The Fiction Writer is at the top of the required reading list for my Writer’s Workshop students. With its engagingly direct, conversational style and easily accessible format, it is a veritable cornucopia of hands-on help for aspiring writers of any age…the quintessential guidebook for the soon-to-be-published.”—Susan McLemore, Writing Instructor

The Fiction Writer “is the most practical book on publishing that I’ve ever read, and I’ve read them all! Not only is each chapter packed with advice for writers at every level of the publishing process, but the text is highly readable and even entertaining. The clear format, the direct style and the playful layout keep the large volume of information from ever becoming dry or boring.

The Fiction Writer “is the most practical book on publishing that I’ve ever read, and I’ve read them all! Not only is each chapter packed with advice for writers at every level of the publishing process, but the text is highly readable and even entertaining. The clear format, the direct style and the playful layout keep the large volume of information from ever becoming dry or boring.