“By failing to engage with climate change, artists and writers are contributing to an impoverished sense of the world, right at the moment when art and literature are most needed to galvanize a grassroots movement in favor of climate justice and carbon mitigation.”—Amitav Ghosh, 2017

…Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood. Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl or The Water Knife. Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140. Nina Munteanu’s A Diary in the Age of Water. Richard Power’s Overstory. Annie Proulx’s Barkskins. Emmi Itäranta’s The Memory of Water…

What these novels have in common is that they are all Dystopian Eco-Fiction. Humanity’s key role in environmental destruction serves a strong thematic element. In eco-fiction dystopias (as opposed to political or socio-cultural dystopias such as Brave New World, 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale) the environment—whether forest, ocean, water generally, or the animal world—plays a key character.

What these novels have in common is that they are all Dystopian Eco-Fiction. Humanity’s key role in environmental destruction serves a strong thematic element. In eco-fiction dystopias (as opposed to political or socio-cultural dystopias such as Brave New World, 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale) the environment—whether forest, ocean, water generally, or the animal world—plays a key character.

Our Literature in the Anthropocene

In 2017, Amitav Ghosh observed that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable). “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” writes Fredrick Albritton Jonsson of The Guardian, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’”

According to Ghosh, plots and characters of contemporary literature tend to reflect the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depends on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature has been perceived as gradual (or static by some) and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely have been externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

According to Ghosh, plots and characters of contemporary literature tend to reflect the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depends on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature has been perceived as gradual (or static by some) and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely have been externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse.

Jonsson suggests that these Enlightenment ideas are essentially ideological manifestations of Holocene stability, remnants from 11,000 years of small variability in temperature and carbon dioxide levels, giving rise to deep-seated habits and ideas about the resilience of the natural world. “The commitment to indefinite economic growth espoused by the economics profession in the postwar era is perhaps its most triumphant [and dangerous] expression.”

Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.”

Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they certainly will—given their short-term thinking.

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.”

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.”

I suggest widening the genre to include good dystopian eco-fiction, which includes not just post-apocalyptic tales but also cautionary tales, worlds in upheaval, and satires. Dystopian literature is ultimately an exploration of hope through personal experience. The eco-fiction protagonist navigates their dystopia by learning meaningful lessons—lessons that pertain directly to our reader in their current world. This is because the premise of a dystopia lies squarely in the present world. Good dystopias can enlighten and suggest possibilities; they can warn and herald. At the very least, they incite the necessary conversation.

On the Role of Dystopian Eco-Fiction

I recently shared a panel discussion with writer Kristen Kiomall-Evans at the 2019 Limestone Genre Expo in Kingston entitled: “On the Role of (Dystopian) Literature and Environmental Issues: Can Books Save the Planet.” The audience of mostly women shared enlightened input in an open discussion, which spanned a range of topics and directions from what dystopian literature actually is to whether we are turned off by its negativity—that it may be too close to reality and makes us cringe and want to hide. One person even brought up Game of Thrones as an example; which I then bluntly suggested was not real “story”—it is a stream of episodic sensationalism and horror—aimed at thrilling shock value, not fulfilling meaning.

I recently shared a panel discussion with writer Kristen Kiomall-Evans at the 2019 Limestone Genre Expo in Kingston entitled: “On the Role of (Dystopian) Literature and Environmental Issues: Can Books Save the Planet.” The audience of mostly women shared enlightened input in an open discussion, which spanned a range of topics and directions from what dystopian literature actually is to whether we are turned off by its negativity—that it may be too close to reality and makes us cringe and want to hide. One person even brought up Game of Thrones as an example; which I then bluntly suggested was not real “story”—it is a stream of episodic sensationalism and horror—aimed at thrilling shock value, not fulfilling meaning.

The group explored what Eco-Fiction is and the possibility of how eco-fiction writers can influence their audience to engage in helping the planet and humanity, in turn.

“Science doesn’t tell us what we should do,” Barbara Kingsolver wrote in Flight Behavior “It only tells us what is.” Stories can never be a solution in themselves, but they have the capacity to inspire action. Margaret Atwood wrote in MaddAddam, “People need such stories, because however dark, a darkness with voices in it is better than a silent void.”

We explored several areas in which writers could elucidate ways to engage readers for edification, connection and participation. We discussed optimism, new perspectives, envisioning our future, and imaginative use of “product placement” to gain reader engagement and galvanize a movement of action.

Optimism in Story

I pointed out that good dystopias—like all good fiction—follow a character and story arc that must ultimately resolve (which Game of Thrones may never do, certainly not well—J.R.R. Martin’s books series upon which it is based are not even finished yet!). Eco-Fiction Dystopias often conclude with a strong element of hope, based on some positive aspect of humanity and the human spirit—which may include our own evolution. Think Day After Tomorrow, Year of the Flood, Windup Girl, The Postman, Darwin’s Paradox.

In 2015, I joined Lynda Williams of Reality Skimming Press in creating an optimistic science fiction anthology with the theme of water. My foreword to Water addressed this point:

In 2015, I joined Lynda Williams of Reality Skimming Press in creating an optimistic science fiction anthology with the theme of water. My foreword to Water addressed this point:

As we drank Schofferhoffers over salmon burgers, Lynda lamented that while the speculative / science fiction genre has gained a literary presence, this has been at some expense. Much of the current zeitgeist of this genre in Canada tends toward depressing, “self-interested cynicism and extended analogies to drug addiction as a means of coping with reality,” Lynda remarked. Where was the optimism and associated hope for a future? I brought up the “hero’s journey” and its role in meaningful story. One of the reasons this ancient plot approach, based on the hero journey myth, is so popular is that its proper use ensures meaning in story. This is not to say that tragedy is not a powerful and useful story trope; so long as hope for someone—even if just the reader—is generated. Lynda and I concluded that the science fiction genre could use more optimism. [As a result,] these stories explore individual choices and the triumph of human imagination in the presence of adversity. [Each story explores] the surging spirit of humanity toward hopeful shores.

New Perspectives in Story

Evans spoke of the emergence of and need for a strong voice by marginalized groups who would be most affected by things like habitat destruction and climate change. The poor and marginalized will most certainly make up the majority of climate change refugees, starved out and water shorted, and suffering malnutrition, violence and disease.

Evans pointed out that afro-American writers (e.g., Octavia Butler, Walter Mosley, Nalo Hopkinson and N.K. Jemisin) and indigenous writers (Cherie Dimaline, Daniel Wilson, Drew Hayden Taylor) are an exciting voice, providing a new and compelling perspective on ongoing global issues.

Evans pointed out that afro-American writers (e.g., Octavia Butler, Walter Mosley, Nalo Hopkinson and N.K. Jemisin) and indigenous writers (Cherie Dimaline, Daniel Wilson, Drew Hayden Taylor) are an exciting voice, providing a new and compelling perspective on ongoing global issues.

I would add that the “feminine” voice—the voice of women and the voice of ecology and those who embrace the gylanic voice—are needed. This was strangely not mentioned in the group—perhaps because we were all women—but one. Such a voice can help personalize the experience to readers, by creating discovery, connection and understanding—and ultimately serving a key force in engaging readers to act.

Envisioning Our Future Through Story

One audience member shared a yearning for an optimistic focus through an envisioned world where solutions have successfully created that world. She wasn’t so much suggesting writing a utopia, but including elements of future wishes as an integral part of the world, following Ghandi’s wise advice: be the change you seek. In a recent interview in which I also participated in The Globe and Mail on women science fiction writers, Ottawa writer Marie Bilodeau addressed this concept:

“the best part about writing science fiction is showing different ways of being without having your characters struggle to gain rights. Invented worlds can host a social landscape where debated rights in this world – such as gay marriage, abortion and euthanasia – are just a fact of life.”

People are looking for hopeful fiction that addresses the issues but explores a successful paradigm shift. One that accurately addresses our current issues with intelligence and hope. The power of envisioning a certain future is that the vision enables one to see it as possible.

Product Placement in Story

Editor and naturalist Merridy Cox suggested that writers could make motivating connections through altruistic (not market-driven) “product placement.” She gave the example of an Ash tree. The Ash (Fraxinus species) could subtly make its name, its character and ecology known in the story, along with its plight—its destruction by the non-native invasive emerald ash borer. The use of metaphor and personification would easily link the Ash to a character and at the same time illuminate the reader on a real aspect of the environment to consider. Another example she gave was of the threatened bobolink bird, now all but gone. The bobolink originally made its home in the tallgrass prairie and other open meadows. As native prairies were cleared for farming, the bobolink was displaced and moved to living in hayfields and fallow fields—building their nests on the ground in dense grasses. Changing farm practices (shorter crop rotation and earlier maturing seed mixtures) are now destroying the bobolink’s last refuge.

Bobolink mother and her chicks

Such “product placement” essentially gives Nature and the environmental a personalized face that can easily interact with the story’s theme and its characters. “Product placement”—like symbol—lies embedded in its own story. In the case of the bobolink, it is a story of colonialism, exploitation, and single-minded pursuit at the expense of others not considered, known or understood. These examples have anthropogenic connections to human behaviour, action and knowledge—all related to story and theme.

In my new writing guidebook The Ecology of Story: World as Character I discuss and explore how some authors do this impeccably. Authors such as Barbara Kingsolver, Richard Powers, Frank Herbert, Ray Bradbury, Thomas Hardy, Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Janet Fitch, John Steinbeck, David Mitchell, Joanne Harris and many others.

In my new writing guidebook The Ecology of Story: World as Character I discuss and explore how some authors do this impeccably. Authors such as Barbara Kingsolver, Richard Powers, Frank Herbert, Ray Bradbury, Thomas Hardy, Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Janet Fitch, John Steinbeck, David Mitchell, Joanne Harris and many others.

Writing for the Anthropocene

Learn how to write for the Anthropocene: from Habitats and Trophic Levels to Metaphor and Archetype…

Learn the fundamentals of ecology, insights of world-building, and how to master layering-in of metaphoric connections and symbols between setting and character. “Ecology of Story: World as Character” is the 3rd guidebook in Nina Munteanu’s acclaimed “how to write” series for novice to professional writers.

The Ecology of Story will be released by Pixl Press in June 2019.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” will be released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in May 2020.

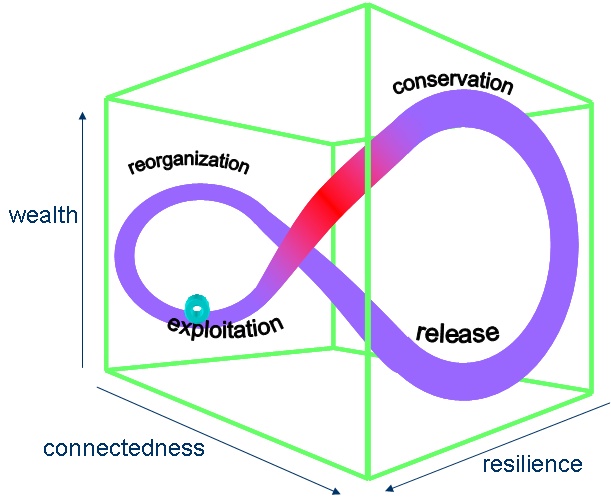

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In  In my speculative fiction novel,

In my speculative fiction novel,

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before;

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before; In my book

In my book

In my upcoming novel “

In my upcoming novel “ In a talk I give at conferences on “

In a talk I give at conferences on “ Terms such as

Terms such as  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness— Canadians are writing more

Canadians are writing more  My short story “

My short story “ Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “

Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the  Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.