There are no boring moments; only bored people who lack the wherewithal to explore and discover—Nina Munteanu

Cedar trees on shore of Jackson Creek, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

So many of us have responded intelligently to the pandemic by respecting “lock down” measures to self-isolate and socially distance. From simply staying at home to going out less often and avoiding crowds (well, there shouldn’t be any of them right now; but there will always be an irresponsible sector who must reflex their sense of entitlement and lack of compassion).

What the pandemic and our necessary reaction to it has done more than anything is to slow us down. Many people are slowly going crazy with it: we are, after all, a gregarious species. And not all of us feel comfortable with virtual meetings. Our senses are deprived; you can’t touch and smell and feel.

But, there are wonderful ways to feed the muse and get sensual…

Cedar tree on Jackson Creek, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

My good friend and poet Merridy Cox recently told me about a Facebook friend who was feeling so bored: “GETTING SO BORED BEING AT HOME” amid the social distancing and self-isolation during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Merridy counselled her friend to go outside and watch spring unfold then find a nice place to sit and write about it. A poem, she suggested: “Little white clouds are scudding across a blue sky. Trees are budding. Birds are migrating. Don’t be bored! Get outside, find a tree and see if there is a bird in it—now, you have enough to write a poem.”

What Merridy was essentially suggesting to her friend was to look outside herself. Reach out in curiosity and discover something. Boredom will fly away with curiosity and can lead to expression through poetry (or photography, sketching, journaling, memoir, or letter writing). When you open your soul to the spirit of exploration, you will find much to discover. When you share with others, you close the gap of isolation from gregariousness and find connection through meaning. The key is in sharing.

In Gifts from the Trail, Stella Body writes that, “Being Creative is a form of self-care and caring for others. The Gift by Lewis Hyde has been cited by Margaret Atwood and many others as what inspired them to share their creative work. Sharing is part of many religions, as part of becoming ‘holy, from the word ‘whole’. When what you share comes from your inner creative impulse, you develop a sense of your own value as an individual. In addition, you transcend your separateness by touching the spirit of another. In this way, all forms of art are therapeutic.”

The key to success in this is to start with 1) motivation, move through to 2) curiosity and discovery, then on to 3) creativity and expression. Sending an old-fashioned letter and handwriting provides a rich opportunity to create and express fully. And it gives us reasons to pursue. Following these three pursuits will enrich your life and provide enrichment to others through sharing.

Woodpecker hole in white pine tree, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Step 1, MOTIVATION: Find several people you wish to communicate with on a deeper level and wish to entertain and inform. Think beyond your Facebook or Twitter audience (though, I do draw inspiration from wishing to share my photography with them). They could even be your next door neighbour! Of course, you need something to share; that’s where Step 2 comes in.

Step 2, CURIOSITY and DISCOVERY: Find a place that you can observe; the natural world is incredibly suited to discovery. Look high and low, slow your pace and use all your senses. Listen. Smell. Feel. Remember to look up. And look down on the ground. Nature hides some of her most precious gems there. Find something familiar and find something new. Invest in a guidebook.

Research what you’ve found on the Internet; find out more about something you’ve observed. For instance, why does the willow have such a shaggy bark? Why do alders grow so well near the edges of streams? What role do sowbugs play in the ecosystem? What do squirrels eat? What is that bird doing on my lawn? Start a phenology study (how something changes over the seasons). Keep tabs on the birds you see and what they’re doing. You can find several examples of mine in the links below.

Research what you’ve found on the Internet; find out more about something you’ve observed. For instance, why does the willow have such a shaggy bark? Why do alders grow so well near the edges of streams? What role do sowbugs play in the ecosystem? What do squirrels eat? What is that bird doing on my lawn? Start a phenology study (how something changes over the seasons). Keep tabs on the birds you see and what they’re doing. You can find several examples of mine in the links below.

Step 3, CREATIVITY and EXPRESSION: Depending on your relationship with people you are writing to and their own interests, you may tailor your letters with printed pictures, sketches and drawings, maps, quotes, and news clippings. This part can be really fun and can draw on all your creative talents. Let what you see and discover inspire you. Find a “story” in it and share it with someone. You can find more examples on ways to express yourself in my guidebook on writing journals: The Journal Writer.

Bench next to cedar trees on Jackson Creek, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Exploring and creativity don’t just cure boredom; they are good for your health:

Expressive writing — whether in the form of journaling, blogging, writing letters, memoir or fiction — improves health. Over the past twenty years, a growing body of literature has shown beneficial effects of writing about traumatic, emotional and stressful events on physical and emotional health. In control experiments with college students, Pennebaker and Beall (1986) demonstrated that college students who wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings for only 15 minutes over four consecutive days, experienced significant health benefits four months later. Long term benefits of expressive writing include improved lung and liver function, reduced blood pressure, reduced depression, improved functioning memory, sporting performance and greater psychological well-being. The kind of writing that heals, however, must link the trauma or deep event with the emotions and feelings they generated. Simply writing as catharsis won’t do.

Expressive writing — whether in the form of journaling, blogging, writing letters, memoir or fiction — improves health. Over the past twenty years, a growing body of literature has shown beneficial effects of writing about traumatic, emotional and stressful events on physical and emotional health. In control experiments with college students, Pennebaker and Beall (1986) demonstrated that college students who wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings for only 15 minutes over four consecutive days, experienced significant health benefits four months later. Long term benefits of expressive writing include improved lung and liver function, reduced blood pressure, reduced depression, improved functioning memory, sporting performance and greater psychological well-being. The kind of writing that heals, however, must link the trauma or deep event with the emotions and feelings they generated. Simply writing as catharsis won’t do.

In Gifts from the Trail, Stella Body writes: “Far more than a quick Selfie, a written response explores the range of the experience. It both saves an instant from being lost in time, and holds on to the live matter of the writer’s feeling. If shared, both writer and audience can return to that moment and draw healing from it. What’s more, as many studies on volunteer work have shown, the process of sharing is a healing act.”

In Part 1 of my writing guidebook The Ecology of Story: World as Character, I talk about many of the interesting things in the natural world around us. In Part 2, I give many of these things meaning in story. The guidebook also has several writing exercises to capture the muse.

In Chapter K of my writing guidebook The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now!, I talk about writing what you know and what you discover. It’s more than you think. “In the 19th-century, John Keats wrote to a nightingale, an urn, a season. Simple, everyday things that he knew,” say Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux in The Writer’s Guide to Creativity. “Walt Whitman described the stars, a live oak, a field…They began with what they knew, what was at hand, what shimmered around them in the ordinary world.”

In Chapter K of my writing guidebook The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now!, I talk about writing what you know and what you discover. It’s more than you think. “In the 19th-century, John Keats wrote to a nightingale, an urn, a season. Simple, everyday things that he knew,” say Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux in The Writer’s Guide to Creativity. “Walt Whitman described the stars, a live oak, a field…They began with what they knew, what was at hand, what shimmered around them in the ordinary world.”

My journal writing guidebook The Journal Writer: Finding Your Voice provides advice and exercises on how to create a positive experience in observing, creating, journaling and letter or memoir writing.

Restoring the Lost Art of Handwriting

Nina writing in Niagara on the Lake (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Handwriting is a wonderful thing. It slows us down. It is a sensual and intimate way for us to express ourselves. I love my handwriting, especially when I am using my favorite pen (my handwriting changes depending on the pen), my Cross fountain pen — usually black. When you use a pen or pencil to express yourself you have more ways to express your creativity. Think of the subtleties of handwriting alone: changing the quality and intensity of strokes; designing your script, using colors, symbols, arrows or lines, using spaces creatively, combining with drawing and sketches. In combination with the paper (which could be lined, textured, colored graphed, etc.), your handwritten expression varies as your many thoughts and moods.

The very act of handwriting focuses you. Writing your words by hand connects you more tangibly to what you’re writing through the physical connection of pen to paper. Researchers have proven that just picking up a pencil and paper to write out your ideas improves your ability to think, process information and solve problems. The actual act of writing out the letters takes a little more work in your brain than just typing them on a keyboard, and that extra effort keeps your mind sharp. Researchers have also shown that writing something out by hand improves your ability to remember it. Handwriting improves memory, increases focus, and the ability to see relationships.

Handwriting fuses physical and intellectual processes. American novelist Nelson Algren wrote, “I always think of writing as a physical thing.” Hemmingway felt that his fingers did much of his thinking for him.

According to Dr. Daniel Chandler, semiotician at Aberystwith University, when you write by hand you are more likely to discover what you want to say. When you write on a computer, you write “cleanly” by editing as you go along and deleting words (along with your first thoughts). In handwriting, everything remains, including the words you crossed out. “Handwriting, both product and process,” says Chandler, “is important … in relation to [your] sense of self.” He describes how the resistance of materials in handwriting increases the sense of self in the act of creating something. There is a stamp of ownership in the handwritten words that enhances a sense of “personal experience.”

According to Dr. Daniel Chandler, semiotician at Aberystwith University, when you write by hand you are more likely to discover what you want to say. When you write on a computer, you write “cleanly” by editing as you go along and deleting words (along with your first thoughts). In handwriting, everything remains, including the words you crossed out. “Handwriting, both product and process,” says Chandler, “is important … in relation to [your] sense of self.” He describes how the resistance of materials in handwriting increases the sense of self in the act of creating something. There is a stamp of ownership in the handwritten words that enhances a sense of “personal experience.”

Path along Credit River, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

I know this is true in my own writing experience. This is why, although I do much of my drafting on the computer, I find that some of my greatest creative moments come to me through the notebook, which I always keep with me. Writing in my own hand is private and resonates with informality and spontaneity (in contrast to the fixed, formal look and public nature of print). Handwriting in a notebook is, therefore, a very supportive medium of discovery and the initial expression of ideas.

Develop interest in life as you see it; in people, things, literature, music—the world is so rich, simply throbbing with treasures, beautiful souls and interesting people. Forget yourself—Henry Miller

References:

Munteanu, Nina. 2009. The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now. Starfire World Syndicate. 294pp

Munteanu, Nina. 2013. The Journal Writer: Finding Your Voice. Pixl Press. 172pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2019. The Ecology of Story: World as Character. Pixl Press. 200pp.

Links:

The Ecology of Story: Revealing Hidden Characters of the Forest

Ecology, Story & Stranger Things

The Little Rouge in Winter: Up Close and Personal

The Phenology of the Little Rouge River and Woodland

White Willow–A Study

The Yellow Birch–A Study

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” will be released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

I remember a wonderful conversation I had several years ago at a conference with another science fiction writer on weird and wonderful protagonists and antagonists. Derek knew me as an ecologist—in fact I’d been invited to do a lecture at that conference entitled

I remember a wonderful conversation I had several years ago at a conference with another science fiction writer on weird and wonderful protagonists and antagonists. Derek knew me as an ecologist—in fact I’d been invited to do a lecture at that conference entitled  I recall Derek’s eagerness to create a story that involved characters who demonstrate saprotrophic traits or even were genuine saprotrophs (in science fiction you can do that—it’s not hard. Check out

I recall Derek’s eagerness to create a story that involved characters who demonstrate saprotrophic traits or even were genuine saprotrophs (in science fiction you can do that—it’s not hard. Check out

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action. This week is a wonderful time to reflect on the past year, 2019. It’s also a good time to be thankful for the things we have: loving family, meaningful friendships, pursuits that fulfill us and a place that nurtures our soul.

This week is a wonderful time to reflect on the past year, 2019. It’s also a good time to be thankful for the things we have: loving family, meaningful friendships, pursuits that fulfill us and a place that nurtures our soul. 2019 saw several of my publications come out. In January 2019 the reprint of my story “

2019 saw several of my publications come out. In January 2019 the reprint of my story “ Impakter Magazine

Impakter Magazine

If I’m in a slump, it’s usually because I can’t figure something out—usually some plot point or character quirk or backstory. What helps me is to put the book I’m working on away and do something else. I know that what I need will come; I just have to let it come on its own terms. The break could even be writing something else, so long as it isn’t my book. Or I could do something else on the book such as edit a certain section or research some element. Other ways I coax my muse back are walks in Nature, reading a good book, visiting the library or a bookstore and cycling. These work really well to take me out of the book and into the muse. When I take my mind out of the direct involvement with the book, I’m letting things outside of me impact me with insight. Invariably that is what happens. I’ll see something or experience something that provides me with a clue or even an epiphany.

If I’m in a slump, it’s usually because I can’t figure something out—usually some plot point or character quirk or backstory. What helps me is to put the book I’m working on away and do something else. I know that what I need will come; I just have to let it come on its own terms. The break could even be writing something else, so long as it isn’t my book. Or I could do something else on the book such as edit a certain section or research some element. Other ways I coax my muse back are walks in Nature, reading a good book, visiting the library or a bookstore and cycling. These work really well to take me out of the book and into the muse. When I take my mind out of the direct involvement with the book, I’m letting things outside of me impact me with insight. Invariably that is what happens. I’ll see something or experience something that provides me with a clue or even an epiphany.

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

I recently gave a 2-hour workshop on “ecology of story” at Calgary’s

I recently gave a 2-hour workshop on “ecology of story” at Calgary’s

Nina is a Canadian scientist and novelist. She worked for 25 years as an environmental consultant in the field of aquatic ecology and limnology, publishing papers and technical reports on water quality and impacts to aquatic systems. Nina has written over a dozen eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy novels. An award-winning short story writer, and essayist, Nina currently lives in Toronto where she teaches writing at the University of Toronto and George Brown College. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…”—a scientific study and personal journey as limnologist, mother, teacher and environmentalist—was picked by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times as 2016 ‘The Year in Reading’. Nina’s most recent novel “A Diary in the Age of Water”— about four generations of women and their relationship to water in a rapidly changing world—will be released in 2020 by Inanna Publications.

Nina is a Canadian scientist and novelist. She worked for 25 years as an environmental consultant in the field of aquatic ecology and limnology, publishing papers and technical reports on water quality and impacts to aquatic systems. Nina has written over a dozen eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy novels. An award-winning short story writer, and essayist, Nina currently lives in Toronto where she teaches writing at the University of Toronto and George Brown College. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…”—a scientific study and personal journey as limnologist, mother, teacher and environmentalist—was picked by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times as 2016 ‘The Year in Reading’. Nina’s most recent novel “A Diary in the Age of Water”— about four generations of women and their relationship to water in a rapidly changing world—will be released in 2020 by Inanna Publications.

I talked about the importance of theme to help determine a story’s beginning and ending. We also discussed the use of theme in memoir to help focus the memoir into a meaningful story with a directed narrative. I discussed the use of the hero’s journey plot approach and its associated archetypes to help determine relevance of events, characters and place: all topics explored in my

I talked about the importance of theme to help determine a story’s beginning and ending. We also discussed the use of theme in memoir to help focus the memoir into a meaningful story with a directed narrative. I discussed the use of the hero’s journey plot approach and its associated archetypes to help determine relevance of events, characters and place: all topics explored in my  While everyone left at six, I stayed on with a friend. I’d booked the night and looked forward to a restful evening among deer, rustling trees and a chorus of birdsong. The owner had left us some leftovers for supper, and, as we dined on a smorgasbord of gourmet food and wine, I reveled in Nature’s meditative sounds. The night sky opened deep and clear with a million stars.

While everyone left at six, I stayed on with a friend. I’d booked the night and looked forward to a restful evening among deer, rustling trees and a chorus of birdsong. The owner had left us some leftovers for supper, and, as we dined on a smorgasbord of gourmet food and wine, I reveled in Nature’s meditative sounds. The night sky opened deep and clear with a million stars.

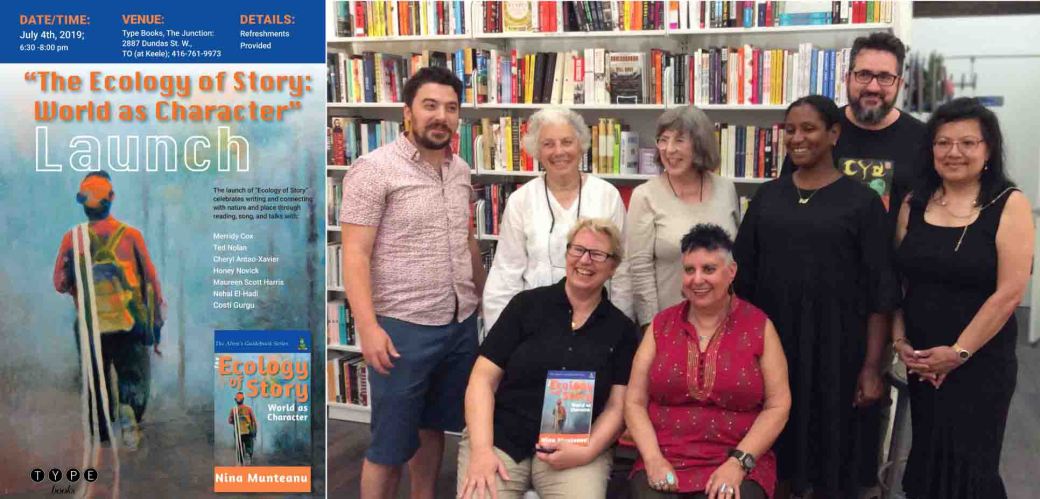

UofT instructor and writer Nina Munteanu launched the third book in her acclaimed “how to write” series at Type Books, Toronto, on July 4th, 2019. The launch of

UofT instructor and writer Nina Munteanu launched the third book in her acclaimed “how to write” series at Type Books, Toronto, on July 4th, 2019. The launch of

Honey Novick is a poet, voice teacher, singer and songwriter. Honey is the winner of the Empowered Poet Award, CAPAC, Yamaha Classical Music Competition in Japan, among others. Honey wrote music for CBC’s Morningside and sang for Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

Honey Novick is a poet, voice teacher, singer and songwriter. Honey is the winner of the Empowered Poet Award, CAPAC, Yamaha Classical Music Competition in Japan, among others. Honey wrote music for CBC’s Morningside and sang for Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau. Ted Nolan—E. Martin Nolan—is a poet, essayist, editor and voice of the trees. He teaches in the Engineering Communication Program at the University of Toronto and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics at York University. His latest work is a chapbook written in collaboration with some trees entitled: “Trees Hate Us.”

Ted Nolan—E. Martin Nolan—is a poet, essayist, editor and voice of the trees. He teaches in the Engineering Communication Program at the University of Toronto and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics at York University. His latest work is a chapbook written in collaboration with some trees entitled: “Trees Hate Us.” Maureen Scott Harris is a poet, essayist, and rare books cataloguer. A UofT grad in Library Science, she received the Trillium Book Award for poetry for Drowning Lessons and was the first non-Australian to be awarded the 2009 WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize for her essay, “Broken Mouth: Offerings for the Don River, Toronto.”

Maureen Scott Harris is a poet, essayist, and rare books cataloguer. A UofT grad in Library Science, she received the Trillium Book Award for poetry for Drowning Lessons and was the first non-Australian to be awarded the 2009 WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize for her essay, “Broken Mouth: Offerings for the Don River, Toronto.” Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, researcher, editor and journalist, who explores the intersections of body, technology, and space. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, literary magazines, and forthcoming in anthologies and edited collections. She is currently a visiting scholar at York University and sessional faculty at the University of Toronto.

Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, researcher, editor and journalist, who explores the intersections of body, technology, and space. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, literary magazines, and forthcoming in anthologies and edited collections. She is currently a visiting scholar at York University and sessional faculty at the University of Toronto. Merridy Cox is a naturalist, photographer, editor, indexer and poet. She is also managing editor of Lyrical Leaf Publishing. Merridy has a degree in biology and museum studies; her poetry focuses mostly on the natural world around her; her poems and photographs are published in several literary anthologies. She has edited several books, including this one!

Merridy Cox is a naturalist, photographer, editor, indexer and poet. She is also managing editor of Lyrical Leaf Publishing. Merridy has a degree in biology and museum studies; her poetry focuses mostly on the natural world around her; her poems and photographs are published in several literary anthologies. She has edited several books, including this one! Costi Gurgu is a graphic designer and illustrator as well as an award-winning science fiction and fantasy novelist and short story writer who is published in anthologies and magazines throughout the world. He is a former lawyer and was art director for lifestyle and fashion magazines in Europe before moving to Canada. His latest novel—RecipeArium—was called the new new weird by Robert J. Sawyer and was nominated for an Aurora Award.

Costi Gurgu is a graphic designer and illustrator as well as an award-winning science fiction and fantasy novelist and short story writer who is published in anthologies and magazines throughout the world. He is a former lawyer and was art director for lifestyle and fashion magazines in Europe before moving to Canada. His latest novel—RecipeArium—was called the new new weird by Robert J. Sawyer and was nominated for an Aurora Award. Cheryl Antao-Xavier is an editor, interior book designer and publisher with IOWI. She has been publishing emergent writers since 2008 and continues to offer self-publishing solutions to writers and companies and organizations. She recently released her book: “Self-Publishing the Professional Way: 5 Steps from Raw Manuscript to Publishing.”

Cheryl Antao-Xavier is an editor, interior book designer and publisher with IOWI. She has been publishing emergent writers since 2008 and continues to offer self-publishing solutions to writers and companies and organizations. She recently released her book: “Self-Publishing the Professional Way: 5 Steps from Raw Manuscript to Publishing.”

“By failing to engage with climate change, artists and writers are contributing to an impoverished sense of the world, right at the moment when art and literature are most needed to galvanize a grassroots movement in favor of climate justice and carbon mitigation.”—Amitav Ghosh, 2017

“By failing to engage with climate change, artists and writers are contributing to an impoverished sense of the world, right at the moment when art and literature are most needed to galvanize a grassroots movement in favor of climate justice and carbon mitigation.”—Amitav Ghosh, 2017 What these novels have in common is that they are all

What these novels have in common is that they are all  According to Ghosh, plots and characters of contemporary literature tend to reflect the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depends on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature has been perceived as gradual (or static by some) and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely have been externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

According to Ghosh, plots and characters of contemporary literature tend to reflect the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depends on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature has been perceived as gradual (or static by some) and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely have been externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.”

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.” I recently shared a panel discussion with writer

I recently shared a panel discussion with writer  In 2015, I joined Lynda Williams of Reality Skimming Press in creating an optimistic science fiction anthology with the theme of water. My foreword to

In 2015, I joined Lynda Williams of Reality Skimming Press in creating an optimistic science fiction anthology with the theme of water. My foreword to

In my new writing guidebook

In my new writing guidebook