The Beaches, Toronto (photo by Nina Munteanu)

The artistic process, whether painting or prose, is admittedly the child of self-expression. The long-standing image of the artist cloistered in her studio—hunched over a writing desk or standing before a canvas to create from the depths of his/her soul—is surely a truism. Artists create from the heart; we dive deep inside our often-tortured souls and closeted past to draw out the universal metaphors that speak to humanity and share—

Ay, there’s the rub. For to share is to have a dialogue and to have a meaningful dialogue is to demonstrate consideration of the other. Somewhere in that journey that began with self, others entered. It is, in fact, something of a paradox and a conundrum for many artists. One that has challenged the artistic community for centuries. It is also why many artists have relied on agents, benefactors, and advocates to effectively communicate, target — and even interpret—their often abstruse “message” to appropriate audiences.

Purists will tell you that a true artist need not consider her audience; because her self-expression naturally finds relevance with the culture and zeitgeist from which she writes through universally understood metaphor: her story is their story.

But is that enough?

I suppose it finally comes down to whether you are interested in sharing. I don’t know any published authors who don’t wish their books to sell. Every storyteller needs an audience to connect with and engage. That is ultimately what good storytelling does: engage, connect, rouse emotions and evoke empathic feelings. Make an impact.

Does identifying and targeting a specific audience result in more satisfied readers and ultimately better sales? Of course it does. The more you—and whoever is helping you market your work—know about your audience, the more likely you are going to attract them to your book, convince them to buy it and ultimately connect with them through story.

That’s the irony of art: it is a treasure that is created out of the depths of solitude but ultimately brought into the light and shared with the world. For your art to have impact, you must know and understand your world.

Knowing your audience will affect every aspect of your book project. It will help determine:

- What your story is about and how you write it (e.g., language, “voice” or personality, narrative style, tone or mood/attitude, characters, setting and theme, even length)

- What genre and sub-genre(s) it lies under

- The look and tone of the cover and blurb (one that matches the story and its audience; I previously wrote about book jacket blurbs and book covers )

- All aspects of promotion, including the language and images you use, where you direct your marketing and how (e.g., medium, timing, etc.)

For your work to succeed, it’s important to consider the following:

Write to the audience’s expectations (given the promise of your work): success of stories with readers will rely on the alignment of expected story structure, tone and endings. My romance SF therefore reads differently from my hard SF in so many ways.

Write to the audience’s expectations (given the promise of your work): success of stories with readers will rely on the alignment of expected story structure, tone and endings. My romance SF therefore reads differently from my hard SF in so many ways. Write to the understanding level of your intended audience: how and what I write for my hard science fiction audience (with expectations on accurate and intelligent exploration and extrapolation on science) is different from the style I use for my historical fantasy. This will include “voice”, language and use of specific vocabulary, terms and concepts, sentence structure and pace.

Write to the understanding level of your intended audience: how and what I write for my hard science fiction audience (with expectations on accurate and intelligent exploration and extrapolation on science) is different from the style I use for my historical fantasy. This will include “voice”, language and use of specific vocabulary, terms and concepts, sentence structure and pace.- Write with the knowledge of your relationship to the reader: how will you gain their empathy and buy-in to your story? This will depend on the genre of your work and expectations of its associated readership.

Understand Your Audience

Who is going to read your work? To what age group to they belong? What culture and sub-culture? What gender(s)? What education and intellectual capacity? Economic status? What regions? What political leanings? Prejudices and beliefs? What knowledge-base? For instance, you wouldn’t use a lot of multi-sylabic latinisms in an action thriller; but you might in a literary fiction or even high fantasy. If you research and create a profile of your intended reader, this will help you identify who you are writing to. “Knowing or anticipating who will be reading what you have written is key to effective writing,” says SkillsYouNeed.com.

It isn’t enough to know who is reading, but why they are reading your writing. Ask yourself these two questions:

- Who do I want to read this? Who are you writing for? They are your primary audience; the ones you will truly resonate with your story; they will be your fans: who are they?

- Who else is likely to read this? This is your secondary audience, readers who may not necessarily read your genre but are interested in the issues or premise of your story or will appreciate how you’ve handled it in your story: who might they be?

Writers are Solopreneurs

In his 2014 article in Forbes, Jayson DeMers shares that: “Market research was once the purview of only big companies. If you weren’t a Fortune 1000 brand, investing in any form of customer research was outside the scope of what many businesses could afford. Today, advances in market research technology have opened a whole range of services to even the smallest businesses. Small enterprises and solopreneurs routinely test ideas before they take them to market, saving tens of thousands of dollars and years of time developing products and services that fall flat with the market.”

Given the current publishing paradigm—which offers less and less to the author, writers are now more than ever required to understand their audience, given their need to be solopreneurs, succeeding on their own know-how, rather than relying on some marketing department that no longer exists.

To know your audience is to know your story better.

A previous version of this article was published in the Clarion Foundation blog and presented by Lynda Williams.

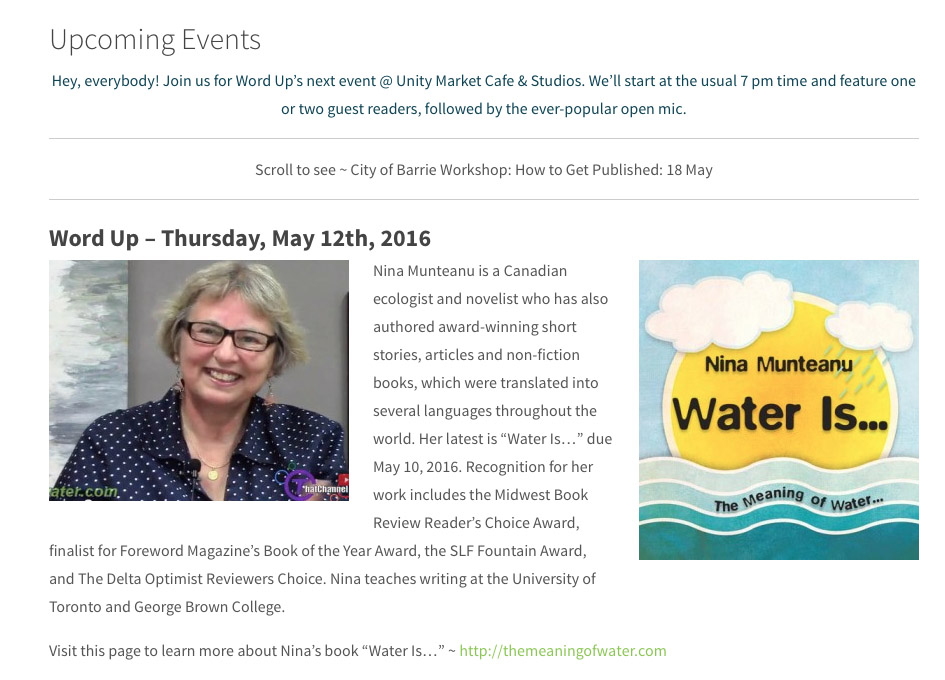

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction. I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it.

I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it. Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility).

Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility). The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II.

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II. The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society.

The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society. The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago.

The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago. In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’”

In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’” Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse.

Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse. Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking.

Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking. In my interview with Mary Woodbury on

In my interview with Mary Woodbury on  My own works of

My own works of

Whether told through cautionary tale / political dystopia (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy; Bong Jung-Ho’s Snowpiercer), or a retooled version of “alien invasion” (e.g., Cixin Liu’s 2015 Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem), these stories all reflect a shift in focus from a technological-centred & human-centred story to a more eco- or world-centred story that explores wider and deeper existential questions. So, yes, science fiction today may appear less technologically imaginative; but it is certainly more sociologically astute, courageous and sophisticated.

Whether told through cautionary tale / political dystopia (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy; Bong Jung-Ho’s Snowpiercer), or a retooled version of “alien invasion” (e.g., Cixin Liu’s 2015 Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem), these stories all reflect a shift in focus from a technological-centred & human-centred story to a more eco- or world-centred story that explores wider and deeper existential questions. So, yes, science fiction today may appear less technologically imaginative; but it is certainly more sociologically astute, courageous and sophisticated. One of the lectures I give to my science fiction writing students is called “Ecology in Storytelling”. It’s usually well attended by writers hoping to gain better insight into world-building and how to master the layering-in of metaphoric connections between setting and character.1

One of the lectures I give to my science fiction writing students is called “Ecology in Storytelling”. It’s usually well attended by writers hoping to gain better insight into world-building and how to master the layering-in of metaphoric connections between setting and character.1 for its larvae. They do this by secreting a chemical that mimics how ants communicate; the ants in turn adopt the newly hatched caterpillars for two years. There’s a terrible side to this story of deception. The Ichneumon wasp, upon finding an Alcon caterpillar inside an ant colony, secretes a pheromone that drives the ants into confused chaos; allowing it to slip through the confusion and lay its eggs inside the poor caterpillar. When the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, the wasp eggs hatch and consume it from inside.

for its larvae. They do this by secreting a chemical that mimics how ants communicate; the ants in turn adopt the newly hatched caterpillars for two years. There’s a terrible side to this story of deception. The Ichneumon wasp, upon finding an Alcon caterpillar inside an ant colony, secretes a pheromone that drives the ants into confused chaos; allowing it to slip through the confusion and lay its eggs inside the poor caterpillar. When the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, the wasp eggs hatch and consume it from inside.

You can read more about this in my book “

You can read more about this in my book “

Neo in The Matrix is an anagram for “One”. Before he changes his name to Neo, he goes by the name of Thomas Anderson. Thomas is Hebrew for “twin” (e.g., Agent Smith tells Neo, “you have been living two lives.”). Of course, Thomas was also one of Jesus’s disciples, the one who doubted. The Wachowski Brothers chose the names of all their main characters with careful purpose. Morpheus (the god of dreams, who takes Neo out of his dream); Trinity (who connects and unifies the “father” the “son” and the “holy spirit” through her faith).

Neo in The Matrix is an anagram for “One”. Before he changes his name to Neo, he goes by the name of Thomas Anderson. Thomas is Hebrew for “twin” (e.g., Agent Smith tells Neo, “you have been living two lives.”). Of course, Thomas was also one of Jesus’s disciples, the one who doubted. The Wachowski Brothers chose the names of all their main characters with careful purpose. Morpheus (the god of dreams, who takes Neo out of his dream); Trinity (who connects and unifies the “father” the “son” and the “holy spirit” through her faith).

Lady Vivianne Schoen, the Baroness von Grunwald, in my historical fantasy The Last Summoner, is a being of light who can travel time-space and must alter history starting with the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. Her first name derives from the Latin vivus meaning alive or the French word vivre for life. And live she must—for over six hundred years— if she is to succeed in recasting history to make this a better world. There is an ironic layer to her name, but I can’t reveal it here for those who haven’t yet read the book. In future Paris she meets François Rabelais, named after the 15th Century satirist, philosopher and dissident. While this youth on the surface represents the antithesis of the medieval scholar, he finally reveals himself as a philosopher warrior and humanist like his 15th Century namesake.

Lady Vivianne Schoen, the Baroness von Grunwald, in my historical fantasy The Last Summoner, is a being of light who can travel time-space and must alter history starting with the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. Her first name derives from the Latin vivus meaning alive or the French word vivre for life. And live she must—for over six hundred years— if she is to succeed in recasting history to make this a better world. There is an ironic layer to her name, but I can’t reveal it here for those who haven’t yet read the book. In future Paris she meets François Rabelais, named after the 15th Century satirist, philosopher and dissident. While this youth on the surface represents the antithesis of the medieval scholar, he finally reveals himself as a philosopher warrior and humanist like his 15th Century namesake.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit