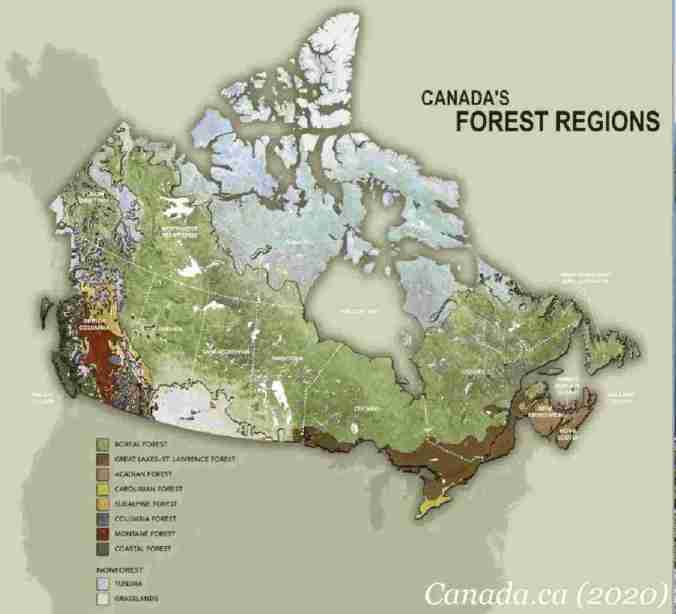

The second leg of my drive west from Peterborough, took me past Thunder Bay, northwest from Lake Superior and into the heart of the boreal forest. Named after Boreas, the Greek god of the Northwind, the boreal forest is also called taiga (a Russian word from Yakut origin that means “untraversable forest”). Canada’s boreal forest is considered the largest intact forest on Earth, with around three million square kilometres still undisturbed by roads, cities and industrial development.

.

The boreal forest is the largest forest region in Ontario, covering two thirds of the province—some 50 million hectares—from the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence forest to the Hudson Bay Lowlands.

I drove the Trans-Canada Highway (Hwy 17) through mixed coniferous forest, wetlands and marsh. The highway generally marks the boundary or transition zone between true Boreal Forest and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest, both dominated by coniferous trees.

.

.

I stopped at English River overnight and the following morning woke to the echoing calls of two loons on the lake. I left at dawn with a peach sky behind me and a dark charcoal sky ahead of me. Soon the dark clouds unburdened themselves and the rain fell in a deluge as I continued west, barely making out the dense forest through flapping windshield wipers. The forest here was a mix of balsam fir, white and black spruce, white pine, aspen and white birch.

.

.

When the rain abated to a steady sprinkle, I ventured out to photograph the spruce-moss-lichen forest by the side of the road. I stood in the drizzle and set up my tripod and camera to take my shots, careful not to tread on the reindeer lichen. Reindeer lichen is highly susceptible to trampling. Branches break off easily and they take decades to recover. This foliose lichen is a key food source for reindeer and caribou during the winter; it also helps stabilize soil and recycles nutrients.

.

.

I drove into the tiny community of Vermillion Bay on Highway 17, looking forward to stopping in Quacker’s Diner for a hearty breakfast as advertised by a fetchy sign on the road. Alas, the place had closed long ago, according to the lady at the Moose Creek Trading Co., and hadn’t been replaced. And she couldn’t suggest anything else in the village. Disappointed, I felt I was truly in the middle of nowhere…

.

Then, a ways down the main road, I spotted the sign: “Nowhere Craft Chocolate & Coffee Roastery” and felt like I’d entered a dream-state where the north was run by hipsters.

.

It was a husband and wife team who ran this wonderful craft bean-to-bar chocolate making and coffee roasting enterprise.

Filling my dark roast coffee order (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

No sooner had I started to feel like I was back in trendy southern Ontario, when I met one of the locals, Simon, who worked in the bush and was patiently waiting for some dark roasts to take back to his buddies. We got to chatting and he shared some colourful stories about ‘the bush’ and folks who live in it, reminding me where I really was.

Coffee in hand, Simon stands next to his ATV with cooler, ready to return to ‘the bush’ with coffee (photo by Nina Munteanu)

When I mentioned the experience to a friend, she made the astute comment: “It is somehow satisfying to think of loggers and trappers and campers emerging out of the forests to go have a great cup of coffee and a hunk of chocolate. Why does that seem totally normal for Canada?”

.

The Nowhere craft chocolate I bought—dark chocolate infused with ginger and Colombian coffee—was the best chocolate I’ve tasted this side of Switzerland. I bought some dark blends of Nowhere Coffee and continued my journey, happy despite no breakfast.

.

Black Spruce Forest

The black spruce (Picea mariana) dominates much of Canada’s boreal forests, frequently occurring in the Canadian Shield ecoregion where it forms extensive stands with groundcover of various mosses and reindeer lichen. Which of the two groundcover types depends on soil conditions and gaps in the forest from disturbance or fire.

Black spruce forest with moss and lichen ground cover, east of Dryden, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

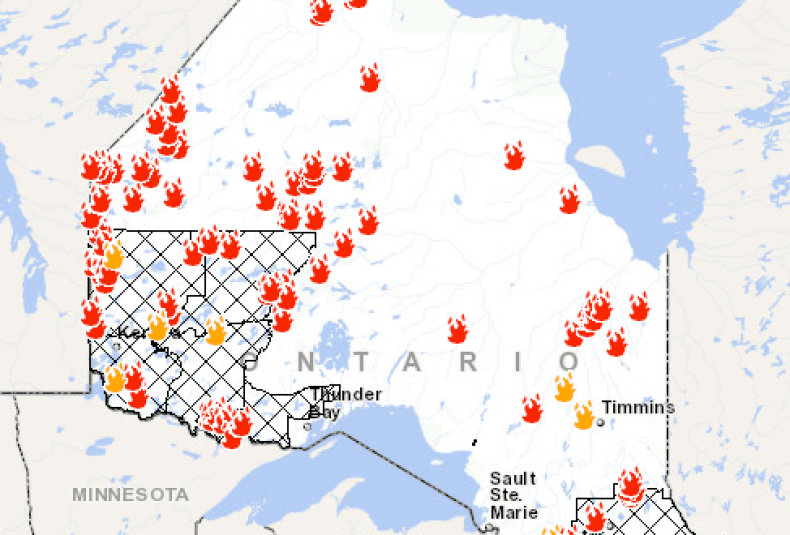

The black spruce tree thrives in acidic peatlands, bogs and poorly drained mineral soils in wet, cold environments, but also grows in drier soils. It is particularly common on histosols (soils with peat and muck) on the Canadian Shield. Fires play a significant role in its regeneration as it replaces pioneer species such as white birch and tamarack after a fire, and grows with lichen and moss.

.

.

Mosses & Lichen Groundcover of Spruce-Dominated Forest

Both mosses and lichen (particularly reindeer lichen) help cool the forest by regulating evaporation and soil temperature; they can also fix nitrogen from the air, providing this key nutrient to an often nitrogen-limited ecosystem.

Spruce-Moss Woodland

.

This spruce-moss woodland is typified by fairly dense closed canopy of black spruce (Picea mariana), along with white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides); this association creates a fairly shaded environment on the forest floor, inviting groundcover of various mosses such as feathermosses and Sphagnum that thrive in stable moist, shaded conditions.

.

.

Common mosses in the spruce-dominated forest include Knight’s Plume Moss (Ptilium crista-castrensis), Red-Stemmed Feathermoss (Pleurozium schreberi), Glittering Feathermoss (Hylocomium splendens), and various species of Sphagnum. Knight’s Plume Moss and Sphagnum are key carbon cyclers in the poorly drained acidic boreal forest, contributing significantly to net primary productivity. They decompose slowly, leading to substantial organic matter accumulation. Sphagnum in particular influences soil organic matter and carbon consumption during wildfires. Due to their ability to retain water, their acidity and resistance to decay, Sphagnum plays a crucial role in both the development and long-term persistence of peatlands where black spruce likes to live.

.

.

Spruce-Lichen Woodland

.

Spruce-lichen woodlands are characterized by an open canopy of black spruce trees, often with jack pine (Pinus banksiana) and white birch (Betula papyrifera) and a ground layer of mostly lichens, particularly fruticose species such as Cladonia rangiferina, C. mitis and C. stellaris. This association is typically found on well-drained, often drier soils and may experience more extreme temperature fluctuations than spruce-moss associations. Through their release of acids that break down rock and organic matter, fruticose lichens contribute to soil formation.

.

.

A dense Cladonia mat also creates a microclimate that helps retain moisture. Lichen may also inhibit spruce regeneration, maintaining the open, park-like nature of lichen woodlands through the release of allelochemicals, such as usnic acid, that inhibit growth of plants and other lichen. Spruce-lichen woodlands may represent a stage in forest succession moving toward a closed-crown forest and may result from fire and insect disturbances that create openings in the forest canopy.

.

.

This is what I observed where I’d stopped the car by the side of the road; closer to the disturbance of the open road, reindeer lichens—likely Cladonia rangiferina, C. mitis and C. stellaris—formed a thick continuous mat on the ground, which was fairly open with young spruce growing here and there. Further up the slope, where the canopy became more closed with mature trees, the mosses dominated the ground.

.

Boreal Wetlands & Kabenung Lake

.

On my drive through the boreal forest north of Wawa, I encountered extensive wetlands—mostly marshes, bogs and fens, forming winding networks of water habitats. These water features are key to the environment’s water regulation, excellent carbon stores and provide habitat for many species. Boreal wetlands are seasonally or permanently waterlogged (up to 2 metres deep) with plant life adapted to wet conditions, including trees, shrubs, grasses, moss and lichen. Organic wetlands (peatlands or muskegs) such as bogs and fens accrue deep organic deposits. Mineral wetlands (marshes, swamps and open water) have shallow organic deposits; these open water systems have nutrient-rich soils.

.

.

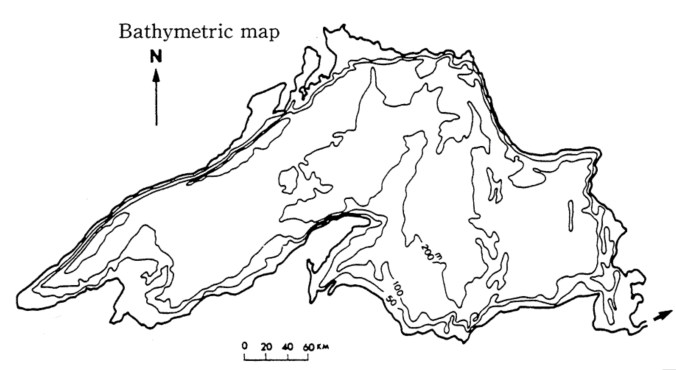

I stopped at Kabenung Lake, considered a prime fishing lake, supporting diverse populations that include Northern Pike, Whitefish, Bass, Walleye, Brook Trout, Lake Trout, and Perch. Judging by the map, I had only a small view of the large convoluted 16 km long lake from the highway. The angler’s bathymetric map suggests a maximum depth of fifteen metres near the lake’s centre.

.

.

Before my journey west took me out of Ontario (and the boreal forest) into Manitoba’s flat prairie, I continued on the Canadian Shield across rugged terrain dominated by conifer trees with ancient Archean rock outcrops of granite and gneiss revealed in rock cuts on the highway. I reached Kenora, a charming old town with character architecture and a vibrant downtown. The town is located in the Lake of the Woods area, near the transition to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest to the south and the Aspen Parkland to the west. I saw lots of spruce, fir and pine alongside birch, maple and poplar. Lake of the Woods is a huge lake about 4349 km2 with over 14,000 islands with a highly convoluted shoreline and serves as an active hub for fishing, recreation and sightseeing.

.

.

In Kenora, I made a short stop at the craft brewery Lake of the Woods Brewing Company, bought some Sneaky Peach Pale Ale to take with me, and continued west to the Manitoba border.

.

On my way, I had to stop the car to let a red fox cross the road. It looked like it owned the road, just sashaying across in a confident trot and smiling at me…Yes, smiling!

.

References:

Houle, Gilles and Louise Fillon. 2003. “The effects of lichens on white spruce seedling establishment and juvenile growth in a spruce-lichen woodland of subarctic Québec.” Ecoscience 10(1): 80-84.

Payette, Serge, Najat Bhiry, Ann Delwaide and Martin Simard. 2000. “Origin of the lichen woodland at its southern range limit in eastern Canada: the catastrophic impact of insect defoliators and fire on the spruce-moss forest.” Canadian J. of Forest Res. 20(2).

Rydin, Håkan, Urban Gunnarsson, and Sebastian Sunberg. 2006. “The Role of Sphagnum in Peatland Development and Persistence.” In: Boreal Peatland Ecology, Ecological Studies 188, R. K. Wieder and D. H. Vitt (eds) Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp 47-65.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

Mapes reveals that her witness tree overcame a 1 in 500 chance of taking root from tiny acorn to seedling to become a thirteen-storey tall giant. Mapes considered her oak a living timeline that revealed through its phenology how climate change is resetting the seasonal clock.

Mapes reveals that her witness tree overcame a 1 in 500 chance of taking root from tiny acorn to seedling to become a thirteen-storey tall giant. Mapes considered her oak a living timeline that revealed through its phenology how climate change is resetting the seasonal clock.

Written with passionate lyricism and a mother’s nurturing spirit, Irish storyteller Beresford-Kroeger weaves a compelling tapestry of ancient forest lore with modern science to promote the global forest. Tapping into aboriginal wisdom and ancient pagan legend, Beresford-Kroeger invites you into the forest to explore the many beneficial and pharmaceutical properties of trees—from leaves that filter the air of particulate pollution, the cardiotonic property of hawthorn, fatty acids in hickory nuts and walnuts that promote brain development, to the aerosols in pine trees that calm nerves.

Written with passionate lyricism and a mother’s nurturing spirit, Irish storyteller Beresford-Kroeger weaves a compelling tapestry of ancient forest lore with modern science to promote the global forest. Tapping into aboriginal wisdom and ancient pagan legend, Beresford-Kroeger invites you into the forest to explore the many beneficial and pharmaceutical properties of trees—from leaves that filter the air of particulate pollution, the cardiotonic property of hawthorn, fatty acids in hickory nuts and walnuts that promote brain development, to the aerosols in pine trees that calm nerves.

In his travels to visit iconic trees around the world, Haskell draws on the wisdom and moral ethics of “ecological aesthetics” to describe a natural beauty—not as individual property but as a world within a world of interactive life to which we belong and serve but do not own:

In his travels to visit iconic trees around the world, Haskell draws on the wisdom and moral ethics of “ecological aesthetics” to describe a natural beauty—not as individual property but as a world within a world of interactive life to which we belong and serve but do not own:

Olivia Vandergriff miraculously survives an electrocution to become an ecowarrior after she begins to hear the voices of the trees. She rallies others to embrace the urgency of activism in fighting the destruction of California’s redwoods and even camps in the canopy of one of the trees to deter the logging. When the ancient tree she has unsuccessfully protected is felled, the sound is “like an artillery shell hitting a cathedral.” Vandergriff weeps for this magnificent thousand-year old tree. So do I. Perhaps the real heroes of this novel are the ancient trees.

Olivia Vandergriff miraculously survives an electrocution to become an ecowarrior after she begins to hear the voices of the trees. She rallies others to embrace the urgency of activism in fighting the destruction of California’s redwoods and even camps in the canopy of one of the trees to deter the logging. When the ancient tree she has unsuccessfully protected is felled, the sound is “like an artillery shell hitting a cathedral.” Vandergriff weeps for this magnificent thousand-year old tree. So do I. Perhaps the real heroes of this novel are the ancient trees.

Proulx immerses the reader in rich sensory detail of a place and time, equally comfortable describing a white pine stand in Michigan and logging camp in Upper Gatineau to a Mi’kmaq village on the Nova Scotia coast or the stately Boston home of Charles Duquet. The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect and a fierce hunger for “more.”

Proulx immerses the reader in rich sensory detail of a place and time, equally comfortable describing a white pine stand in Michigan and logging camp in Upper Gatineau to a Mi’kmaq village on the Nova Scotia coast or the stately Boston home of Charles Duquet. The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect and a fierce hunger for “more.”

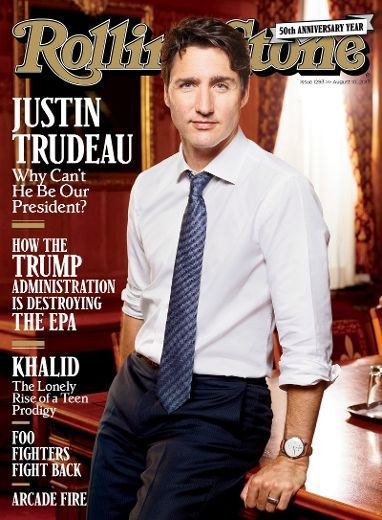

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

To anyone but a Canadian, Trudeau’s remark would rankle, particularly in a time when many western countries are fearfully and angrily turning against immigration through nativism and exclusionary narratives. A time when the United States elected an authoritarian intent on making “America great again” by building walls. A time when populist right-wing political parties hostile to diversity are gaining momentum in other parts of the world. “Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive,” writes Forman. It isn’t, he adds. There are practical reasons for keeping our doors open.

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. We are not a “melting pot” stew of mashed up cultures absorbed into a greater homogeneity of nationalism, no longer recognizable for their unique qualities. Canada isn’t trying to “make Canada great again.”

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness—

We are a northern country with a healthy awareness of our environment—our weather, climate and natural world. This awareness— Canadians are writing more

Canadians are writing more  My short story “

My short story “ Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “

Canadian writer and good friend Claudiu Murgan recently released his book “