Maple spalting with carbon cushion fungus (photo by Nina Munteanu)

One of the most common pieces of advice I give to students of writing in coaching sessions and my classes at UofT (technical and non-fiction writing) and George Brown College (fiction writing) is that active verbs most often work better than passive verbs.

Active Verbs Clarify by Identifying Agent

The use of active verbs avoid confusion because they clearly identify the subject (the doer). For instance, consider these two versions:

ACTIVE: Alice walked the dog.

PASSIVE: The dog was walked.

The active sentence clearly identifies Alice as the one walking the dog; the passive sentence does not provide agency (Alice). We don’t know who walked the dog. When we use active verbs we always know the agent (of change); not so with passive. However, if we modify the passive sentence with “by”, then agency is provided:

PASSIVE (with agency): The dog was walked by Alice.

But the sentence no longer flows easily. This is because the typical subject-verb-object (SVO) flow that we are used to in the English language has changed to object-verb-subject (OVS). If you speak Native Brazilian Hixkaryana, you might be OK with that, given they organize their sentences this way. But that is not how we think and read. Here’s another example:

PASSIVE: The report was written by Ahmed, and it was found to be excellent

ACTIVE: Ahmed wrote the report and it was excellent.

ACTIVE BETTER: Ahmed wrote an excellent report.

Active Verbs Clarify and Empower by Reducing Need for Modifiers

Another reason to use active verbs is that a writer depends less on modifiers to prop up a weak verb, which passive verbs tend to be. For instance, which version is more compelling and easy to take in?

-

Jill was walking quickly into the room.

-

Jill rushed into the room.

The example below that I explore in my book The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now! shows how the use of active and powerful verbs adds vividness and clarity to a scene.

|

PASSIVE |

ACTIVE |

| Joe walked slowly into the room.

|

Joe sidled into the room.

|

| The naked couple were in the bed almost buried under the rumpled covers. They were now struggling to get up.

|

The naked couple struggled out from the rumple of clothes and blankets.

|

| Joe saw the big man sit up and stare at him angrily.

|

The man reared up and glared at Joe.

|

| TOTAL WORDS: 38 | TOTAL WORDS: 25 |

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

When Passive Verbs Clarify…

In Chapter 17 of their book The Craft of Research (University of Chicago Press) Wayne C. Booth and colleagues stress that mindlessly adhering to the tacit rule to choose active verbs over passive verbs can in fact cloud a sentence. They suggest asking a simpler question: do your sentences begin with familiar information, preferably a main character? “If you put familiar characters in your subjects, you will use the active and passive properly,” they say.

It’s all about context.

Booth et al. provide two passages and ask you to choose which “flows” more easily:

-

The quality of our air and even the climate of the world depend on healthy rain forests in Asia, Africa, and South America. But the increasing demand for more land for agricultural use and for wood products for construction worldwide now threatens these rain forests with destruction.

-

The quality of our air and even the climate of the world depend on healthy rain forests in Asia, Africa, and South America. But these rain forests are now threatened with destruction by the increasing demand for more land for agricultural use and for wood products used in construction worldwide.

Most readers will find that 2. flows more easily. This is because the beginning of the second sentence picks up on the “character” (the rain forest) introduced at the end of the first sentence (…the rain forests in Asia, Africa, and South America. But these rain forests…). In the active verb version of 1. the second sentence starts with new information unconnected to the first sentence. The sentences don’t flow into each other as well.

The passive version (2.) permitted the reader to continue with the familiar “character” right away. This, argue Booth et al., is the main function of the passive: to build sentences that begin with older information. The other reason version 2. works better is that the second sentence opens with something short, simple and easy to read: These rain forests are now threatened. In the active version 1. the second sentence opens with something long and complex. The key to clarity is to start simple (and strong, with a “character”) and end with complexity; this way, you set up the reader to better understand by starting with familiar/simple and moving to new/complex.

In engineering and the sciences where I teach at UofT, teachers still demand the use of passive verbs, believing that this makes the writing more objective. This advice is often equally misleading. Booth again provide two passages to show this:

-

Eye movements were measured at tenth-of-second intervals.

-

We measured eye movements at tenth-of-second intervals.

In fact, both sentences are equally objective; however, their stories differ. Version 1. ignores the person doing the measuring and focuses on the measurement. Avoiding “we” or “I” doesn’t make it more objective; it does, however shift the focus of the narrative. There is another explanation for using the passive version of 1. vs. the active 2. When a scientist uses the passive to describe a process, she implies that the process can be repeated by anyone—much like providing a recipe that anyone can follow.

Consider the following two passages:

-

It can be concluded that the fluctuations result from the Burnes effect.

-

We conclude that the fluctuations result from the Burnes effect.

The active verb in 2. conclude and we as subject refers to actions that only the writer / researcher can perform. In other words, they are taking responsibility for that conclusion. Anyone can measure; only the author / researcher can claim what their research means.

The lesson here is that there is no one magic stick for sentence structure and active vs. passive verb use. Reader-ease and clarity depends on context and a natural flow of ideas.

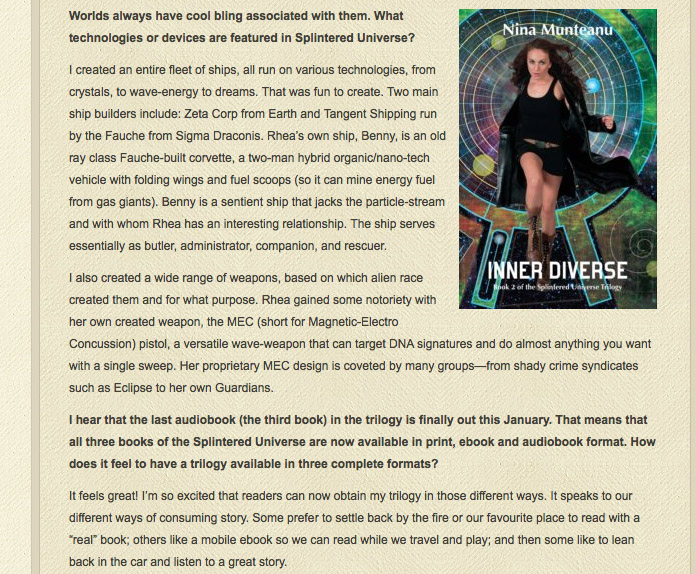

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” will be released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

This week is a wonderful time to reflect on the past year, 2019. It’s also a good time to be thankful for the things we have: loving family, meaningful friendships, pursuits that fulfill us and a place that nurtures our soul.

This week is a wonderful time to reflect on the past year, 2019. It’s also a good time to be thankful for the things we have: loving family, meaningful friendships, pursuits that fulfill us and a place that nurtures our soul. 2019 saw several of my publications come out. In January 2019 the reprint of my story “

2019 saw several of my publications come out. In January 2019 the reprint of my story “ Impakter Magazine

Impakter Magazine

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

I recently gave a 2-hour workshop on “ecology of story” at Calgary’s

I recently gave a 2-hour workshop on “ecology of story” at Calgary’s

Nina is a Canadian scientist and novelist. She worked for 25 years as an environmental consultant in the field of aquatic ecology and limnology, publishing papers and technical reports on water quality and impacts to aquatic systems. Nina has written over a dozen eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy novels. An award-winning short story writer, and essayist, Nina currently lives in Toronto where she teaches writing at the University of Toronto and George Brown College. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…”—a scientific study and personal journey as limnologist, mother, teacher and environmentalist—was picked by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times as 2016 ‘The Year in Reading’. Nina’s most recent novel “A Diary in the Age of Water”— about four generations of women and their relationship to water in a rapidly changing world—will be released in 2020 by Inanna Publications.

Nina is a Canadian scientist and novelist. She worked for 25 years as an environmental consultant in the field of aquatic ecology and limnology, publishing papers and technical reports on water quality and impacts to aquatic systems. Nina has written over a dozen eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy novels. An award-winning short story writer, and essayist, Nina currently lives in Toronto where she teaches writing at the University of Toronto and George Brown College. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…”—a scientific study and personal journey as limnologist, mother, teacher and environmentalist—was picked by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times as 2016 ‘The Year in Reading’. Nina’s most recent novel “A Diary in the Age of Water”— about four generations of women and their relationship to water in a rapidly changing world—will be released in 2020 by Inanna Publications.

I talked about the importance of theme to help determine a story’s beginning and ending. We also discussed the use of theme in memoir to help focus the memoir into a meaningful story with a directed narrative. I discussed the use of the hero’s journey plot approach and its associated archetypes to help determine relevance of events, characters and place: all topics explored in my

I talked about the importance of theme to help determine a story’s beginning and ending. We also discussed the use of theme in memoir to help focus the memoir into a meaningful story with a directed narrative. I discussed the use of the hero’s journey plot approach and its associated archetypes to help determine relevance of events, characters and place: all topics explored in my  While everyone left at six, I stayed on with a friend. I’d booked the night and looked forward to a restful evening among deer, rustling trees and a chorus of birdsong. The owner had left us some leftovers for supper, and, as we dined on a smorgasbord of gourmet food and wine, I reveled in Nature’s meditative sounds. The night sky opened deep and clear with a million stars.

While everyone left at six, I stayed on with a friend. I’d booked the night and looked forward to a restful evening among deer, rustling trees and a chorus of birdsong. The owner had left us some leftovers for supper, and, as we dined on a smorgasbord of gourmet food and wine, I reveled in Nature’s meditative sounds. The night sky opened deep and clear with a million stars.

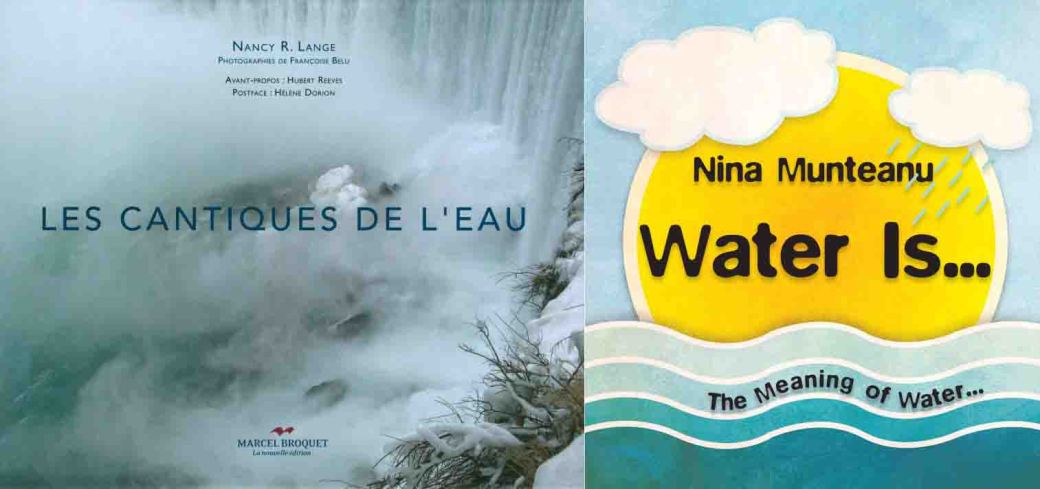

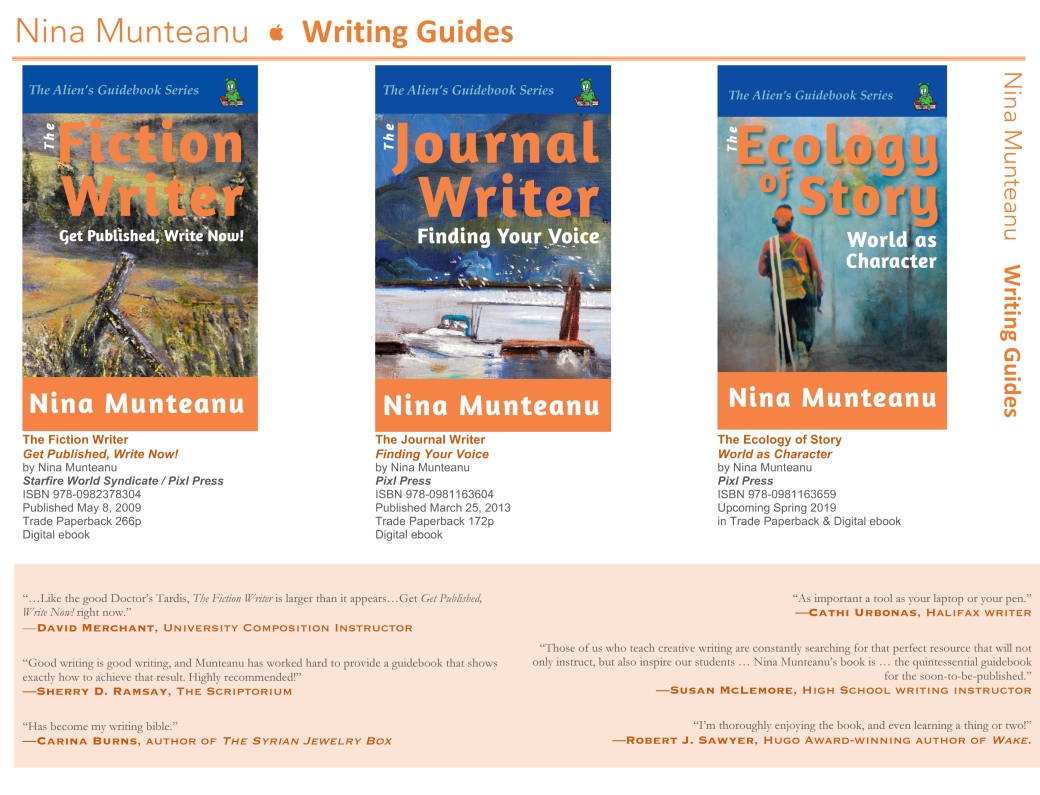

UofT instructor and writer Nina Munteanu launched the third book in her acclaimed “how to write” series at Type Books, Toronto, on July 4th, 2019. The launch of

UofT instructor and writer Nina Munteanu launched the third book in her acclaimed “how to write” series at Type Books, Toronto, on July 4th, 2019. The launch of

Honey Novick is a poet, voice teacher, singer and songwriter. Honey is the winner of the Empowered Poet Award, CAPAC, Yamaha Classical Music Competition in Japan, among others. Honey wrote music for CBC’s Morningside and sang for Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

Honey Novick is a poet, voice teacher, singer and songwriter. Honey is the winner of the Empowered Poet Award, CAPAC, Yamaha Classical Music Competition in Japan, among others. Honey wrote music for CBC’s Morningside and sang for Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau. Ted Nolan—E. Martin Nolan—is a poet, essayist, editor and voice of the trees. He teaches in the Engineering Communication Program at the University of Toronto and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics at York University. His latest work is a chapbook written in collaboration with some trees entitled: “Trees Hate Us.”

Ted Nolan—E. Martin Nolan—is a poet, essayist, editor and voice of the trees. He teaches in the Engineering Communication Program at the University of Toronto and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics at York University. His latest work is a chapbook written in collaboration with some trees entitled: “Trees Hate Us.” Maureen Scott Harris is a poet, essayist, and rare books cataloguer. A UofT grad in Library Science, she received the Trillium Book Award for poetry for Drowning Lessons and was the first non-Australian to be awarded the 2009 WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize for her essay, “Broken Mouth: Offerings for the Don River, Toronto.”

Maureen Scott Harris is a poet, essayist, and rare books cataloguer. A UofT grad in Library Science, she received the Trillium Book Award for poetry for Drowning Lessons and was the first non-Australian to be awarded the 2009 WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize for her essay, “Broken Mouth: Offerings for the Don River, Toronto.” Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, researcher, editor and journalist, who explores the intersections of body, technology, and space. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, literary magazines, and forthcoming in anthologies and edited collections. She is currently a visiting scholar at York University and sessional faculty at the University of Toronto.

Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, researcher, editor and journalist, who explores the intersections of body, technology, and space. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, literary magazines, and forthcoming in anthologies and edited collections. She is currently a visiting scholar at York University and sessional faculty at the University of Toronto. Merridy Cox is a naturalist, photographer, editor, indexer and poet. She is also managing editor of Lyrical Leaf Publishing. Merridy has a degree in biology and museum studies; her poetry focuses mostly on the natural world around her; her poems and photographs are published in several literary anthologies. She has edited several books, including this one!

Merridy Cox is a naturalist, photographer, editor, indexer and poet. She is also managing editor of Lyrical Leaf Publishing. Merridy has a degree in biology and museum studies; her poetry focuses mostly on the natural world around her; her poems and photographs are published in several literary anthologies. She has edited several books, including this one! Costi Gurgu is a graphic designer and illustrator as well as an award-winning science fiction and fantasy novelist and short story writer who is published in anthologies and magazines throughout the world. He is a former lawyer and was art director for lifestyle and fashion magazines in Europe before moving to Canada. His latest novel—RecipeArium—was called the new new weird by Robert J. Sawyer and was nominated for an Aurora Award.

Costi Gurgu is a graphic designer and illustrator as well as an award-winning science fiction and fantasy novelist and short story writer who is published in anthologies and magazines throughout the world. He is a former lawyer and was art director for lifestyle and fashion magazines in Europe before moving to Canada. His latest novel—RecipeArium—was called the new new weird by Robert J. Sawyer and was nominated for an Aurora Award. Cheryl Antao-Xavier is an editor, interior book designer and publisher with IOWI. She has been publishing emergent writers since 2008 and continues to offer self-publishing solutions to writers and companies and organizations. She recently released her book: “Self-Publishing the Professional Way: 5 Steps from Raw Manuscript to Publishing.”

Cheryl Antao-Xavier is an editor, interior book designer and publisher with IOWI. She has been publishing emergent writers since 2008 and continues to offer self-publishing solutions to writers and companies and organizations. She recently released her book: “Self-Publishing the Professional Way: 5 Steps from Raw Manuscript to Publishing.”

In Animal Farm, George Orwell uses animals to describe the revolution against a totalitarian regime (e.g. the overthrow of the last Russian Csar and the Communist Revolution of Russia). The animals embrace archetypes to symbolize the actions and thoughts of various sectors within that world. The pigs are the leaders of the revolution; Mr. Jones represents the ruling despot who is overthrown; the horse Boxer is the ever-loyal and unquestioning labor class.

In Animal Farm, George Orwell uses animals to describe the revolution against a totalitarian regime (e.g. the overthrow of the last Russian Csar and the Communist Revolution of Russia). The animals embrace archetypes to symbolize the actions and thoughts of various sectors within that world. The pigs are the leaders of the revolution; Mr. Jones represents the ruling despot who is overthrown; the horse Boxer is the ever-loyal and unquestioning labor class. In Lord of the Flies, William Golding explores the conflict in humanity between the impulse toward civilization and the impulse toward savagery. The symbols of the island, the ocean, the conch shell, Piggy’s glasses, and the Lord of the Flies, or the Beast, represent central ideas that reinforce this main theme. Each character has recognizable symbolic significance: Ralph represents civilization and democracy; Piggy represents intellect and rationalism; Jack represents self-interested savagery and dictatorship; and Simon (the outsider in so many ways) represents altruistic purity.

In Lord of the Flies, William Golding explores the conflict in humanity between the impulse toward civilization and the impulse toward savagery. The symbols of the island, the ocean, the conch shell, Piggy’s glasses, and the Lord of the Flies, or the Beast, represent central ideas that reinforce this main theme. Each character has recognizable symbolic significance: Ralph represents civilization and democracy; Piggy represents intellect and rationalism; Jack represents self-interested savagery and dictatorship; and Simon (the outsider in so many ways) represents altruistic purity. Excellent examples of satires with less obvious allegorical structure (but it’s there) can be found in the genre of science fiction—a highly metaphorical literature that makes prime use of place and setting with archetypal characters to satirize an aspect of society. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley is a satirical response to his observation of humans’ addiction to (sexual) pleasure and vulnerability to mind control and the dumbing of civilization in the 1930s. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eight-Four satirizes humanity’s vulnerability to fascism, based on his perception of humans’ sense of fear and helplessness under powerful governments and their oppressive surveillance. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale satirizes a society in which a woman struggles in a fundamentalist Christian dictatorship patriarchy where women are forced into a system of sexual slavery for the ruling patriarchy.

Excellent examples of satires with less obvious allegorical structure (but it’s there) can be found in the genre of science fiction—a highly metaphorical literature that makes prime use of place and setting with archetypal characters to satirize an aspect of society. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley is a satirical response to his observation of humans’ addiction to (sexual) pleasure and vulnerability to mind control and the dumbing of civilization in the 1930s. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eight-Four satirizes humanity’s vulnerability to fascism, based on his perception of humans’ sense of fear and helplessness under powerful governments and their oppressive surveillance. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale satirizes a society in which a woman struggles in a fundamentalist Christian dictatorship patriarchy where women are forced into a system of sexual slavery for the ruling patriarchy. This article is an excerpt from “

This article is an excerpt from “

“I was fascinated by Nina’s clear and extremely interesting lecture on the hero’s journey. Maybe all writers have a novel in their heads they want to write one day, and the techniques Nina shared with us will help me when I get to that point. In fact, because of her, I may get there a lot sooner than I had planned.”— Zoe M. Hicks, Saint Simon’s Island, GA

“I was fascinated by Nina’s clear and extremely interesting lecture on the hero’s journey. Maybe all writers have a novel in their heads they want to write one day, and the techniques Nina shared with us will help me when I get to that point. In fact, because of her, I may get there a lot sooner than I had planned.”— Zoe M. Hicks, Saint Simon’s Island, GA

“…Like the good Doctor’s Tardis, The Fiction Writer is larger than it appears… Get Get Published, Write Now! right now.”—David Merchant, Creative Writing Instructor

“…Like the good Doctor’s Tardis, The Fiction Writer is larger than it appears… Get Get Published, Write Now! right now.”—David Merchant, Creative Writing Instructor