Craig H. Bowlsby is a writer from Vancouver whose story “The Girl Who Was Only Three Quarters Dead,” published in the April 2022 Issue of Mystery Magazine was just recently declared the Winner of the Crime Writers of Canada Award of Excellence for Best Crime Short Story for 2023.

This noir/ dystopian story, set in Vancouver B.C., finds Suki prematurely awoken from an induced suspension between being alive and dead. With her retinas deactivated and her Government persona suspended, it’s up to her long-time friend and private investigator, Gabe, to uncover why she was brought back early and the way forward to recover her identity. Through the gritty and flooded streets of East End Vancouver and the mega corporations who control their entire existence, Gabe and Suki scheme to claim what is rightfully Suki’s.

Crime Writers of Canada

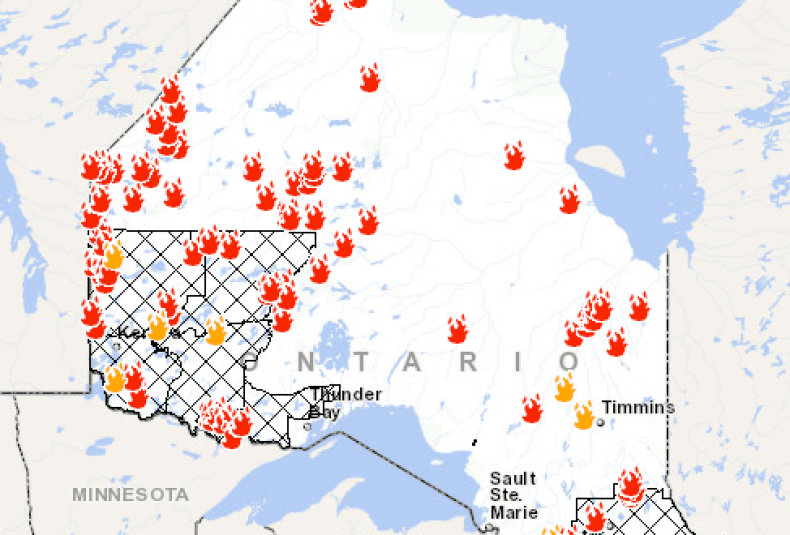

The story is set in the near-future in a post climate change Vancouver when sea level rise has water lapping decrepit buildings north of The Oak Street Bridge on Oak and 77th, Amazon owns entire roadways, and people pay corporate credits as currency.

One of the aspects of this mystery story that I found particularly attractive and interesting was Bowlsby’s use of cross-genre (mystery with science fiction), which he indicated in his interview with Erik D’Souza with Crime Writers of Canada he has an affinity for. I was reminded of the eco-techno thriller style of Hayden Trenholm’s detective series The Steele Chronicles, also set in the near future in Alberta Canada where biotechnology strays into the hands of corporate moguls and fundamentalist cults.

Bowlsby manages to cram both rich and seamless world building in his story (a feat in any short story), addressing mundane aspects of life, including the nuances of language (e.g. swear words suited to the time and place). Deadland, for instance, is a slang word that describes a government program that allows people to temporarily commit suicide, allowing them to place their lives on hold to supposedly help them escape their problems and supposedly better cope later (Bowlsby tells us rather pithily that it doesn’t really work).

Characters were fully fleshed out and interesting and I found that I would very much like to see more stories set in this universe with Gabe and Suki.

Interview

NM: One of the first things I noticed and loved about the story is its title. How did you arrive at it? Is there a story behind the choice?

CHB: There’s usually more than one story behind my titles. It started with a very different title for a couple of years. Then I began to revise the story very seriously and that meant I had to reconsider the title too. I postulated hundreds of titles over three more years and ended up with a new one. But a friend pointed out a slight logic problem with that new title, related to the story. So, I had another reason to work on it. Normally if it doesn’t feel right, I always look for something that resonates better. Finally, this one resonated well, and wouldn’t be shaken off.

NM: What was the spark or inspiration for this story? Why did you set it where and when you did (post-climate-change Vancouver)?

CHB: Well, when Erik De Souza asked me about the social commentary of the story in his interview, I forgot that the germ of the first inkling of this story came from a discussion I had with a friend, twenty years ago, who felt that everything in our society should be available for sale. For him that represented a pure state that would fix all our problems. (Sorry Erik—I’ll explain this when I see you next.) I disagreed, but I wondered what it would be like if we started on that path. So as a social background, the characters are acting within a stage created for such a system—a system just starting to find its own steady legs. I don’t say it’s bad or good—I just give it free rein. The story itself came from other elements, but the characters’ difficulties are complicated by the hyper-capitalism. As for the climate change problem, and the flooding, that came naturally with the near-future time period; I’m afraid it’s going to happen no matter what we do. As for Suki, her main problem stems from an idea I had about how we might alleviate suicides. Even if it might not work very well.

NM: In your interview with Erik, you both discussed the use of language as a way to describe the world and create the gritty noir tone of the story. Can you describe some of the ways you derived them and other techniques you used?

CHB: That was hard. Or at least, it forced me to work my synapses hard for years. I don’t really know how I came up with the language changes except I set myself that task and used my brain like a sifter. I needed words for certain kinds of things, put myself into the future, and rattled hundreds of words through the filter. I kept lists of possibilities and used the best ones. I suppose that helps create the tone, but a lot of things do that: attitudes, social background, plot, etc.

NM: You mentioned in your interview with Erik that this story was “essentially a failure” and you’d been tirelessly working on it for five years, polishing, changing, revising—until finally someone liked it. Can you describe the process you went through in writing, preparing and getting out this story? Was this an exception for you or part of a typical process?

CHB: A typical process. Only a few of my stories have been published without being rejected by other publications. This story was first a short story, then a screenplay for a long time, then back to a short story, which meant at that point I had to cut out many scenes. Then it failed many more times in other publications. I just felt though that it generated so many sparks in my mind that it should catch fire somewhere, sometime. It was a surprise when it did. So, for some reason my stories need a lot of work. I’m guilty, therefore, I suppose, of not giving a story time enough time to mature, so in the future I should probably take more time to revise things before they see an editor. Generally, that’s a good approach, though, because you can come up with things that work better if you give them time to appear, which is what happened with this story.

NM: Your writing has covered non-fiction and many genres of fiction: science fiction, fantasy, space adventure, mystery, thrillers. How would you describe yourself as a writer?

CHB: An activationist. But I just made that up because of your question. I get an idea and I have to activate it, no matter the theme or genre. I don’t see myself restricted in any way to theme or subject. But I definitely feel an affinity for a plodding detective, no matter the time period or plot. (Or plod).

NM: What’s next for Craig H. Bowlsby?

CHB: I have several projects ready or pounding on my skull to get out. I have a series of three novels in the works about a Shanghai detective in 1917. Two in this series are complete. One takes place mostly in Shanghai; the next mostly in Vancouver; and the third will take place in Shanghai again.

NM: Now that you’re rich and famous, will you still talk to me? I’ll be in Vancouver soon and would gladly celebrate, starting with you buying me a beer!

CHB: I guess that sounds fair. Although I think I already owe you a six-pack. I enjoy our discussions, Nina. See you then!

You can read Craig’s story in the April 2022 Issue of Mystery Magazine. You can listen to Craig’s interview with Erik D’Souza here.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.