In December 2017, “Water”, the first of Reality Skimming Press’s Optimistic Sci-Fi Series was released in Vancouver, BC. I was invited to be one of the editors for the anthology, given my passion for and experience with water.

In December 2017, “Water”, the first of Reality Skimming Press’s Optimistic Sci-Fi Series was released in Vancouver, BC. I was invited to be one of the editors for the anthology, given my passion for and experience with water.

This is how Reality Skimming Press introduces the series:

Reality Skimming Press strives to see the light in the dark world we live in, so we bring to you the optimistic science fiction anthology series. Water is the first book in the series, and is edited by author and scientist Nina Munteanu. Six authors thought optimistically about what Earth will be like in terms of water in the near future and provide us with stories on that theme. Step into the light and muse with us about the world of water.

Editing “Water” was a remarkable experience, best described in my Foreword to the anthology:

Lynda Williams

This anthology started for me in Summer of 2015, when Lynda Williams (publisher of RSP) and I were sitting on the patio of Sharky’s Restaurant in Ladner, BC, overlooking the mouth of the Fraser River. As we drank Schofferhoffers over salmon burgers, Lynda lamented that while the speculative / science fiction genre has gained a literary presence, this has been at some expense. Much of the current zeitgeist of this genre in Canada tends toward depressing, “self-interested cynicism and extended analogies to drug addiction as a means of coping with reality,” Lynda remarked.

lunch at Sharky’s

Where was the optimism and associated hope for a future? I brought up the “hero’s journey” and its role in meaningful story. One of the reasons this ancient plot approach, based on the hero journey myth, is so popular is that its proper use ensures meaning in story. This is not to say that tragedy is not a powerful and useful story trope; so long as hope for someone—even if just the reader—is generated. Lynda and I concluded that the science fiction genre could use more optimism. Reality Skimming Press is the result of that need and I am glad of it.

In the years that followed, Reality Skimming Press published several works, including the “Megan Survival” Anthology for which I wrote a short story, “Fingal’s Cave”. It would be one of several works that I produced on the topic of water.

In the years that followed, Reality Skimming Press published several works, including the “Megan Survival” Anthology for which I wrote a short story, “Fingal’s Cave”. It would be one of several works that I produced on the topic of water.

As a limnologist (freshwater scientist), I am fascinated by water’s anomalous and life-giving properties and how this still little understood substance underlies our lives in so many ways. We—like the planet—are over 70% water. Water dominates the chemical composition of all organisms and is considered by many to be the most important substance in the world. The water cycle drives every process on Earth from the movement of cells to climate change. Water is a curious gestalt of magic and paradox, cutting recursive patterns of creative destruction through the landscape. It changes, yet stays the same, shifting its face with the climate. It wanders the earth like a gypsy, stealing from where it is needed and giving whimsically where it isn’t wanted; aggressive yet yielding. Life-giving yet dangerous. Water is a force of global change, ultimately testing our compassion and wisdom as participants on a grand journey.

When Reality Skimming invited me to be editor of their first anthology in their hard science optimistic series, and that it would be about water, I was delighted and excited.

Illustration by Digbejoy Gosh for Bruce Meyer’s “The River Tax”

The six short stories captured here flow through exotic landscapes, at once eerie and beautiful. Each story uniquely explores water and our relationship with its profound and magical properties: melting glaciers in Canada’s north; water’s computing properties and weather control; water as fury and the metaphoric deluge of flood; mining space ice from a nearby comet; water as shapeshifter and echoes of “polywater”. From climate fiction to literary speculative fiction; from the fantastic to the purest of science fiction and a hint of horror—these stories explore individual choices and the triumph of human imagination in the presence of adversity.

I invite you to wade in and experience the surging spirit of humanity toward hopeful shores.

Nina Munteanu, M. Sc., R.P.Bio.

Author of Water Is…

October, 2017

Toronto, Canada

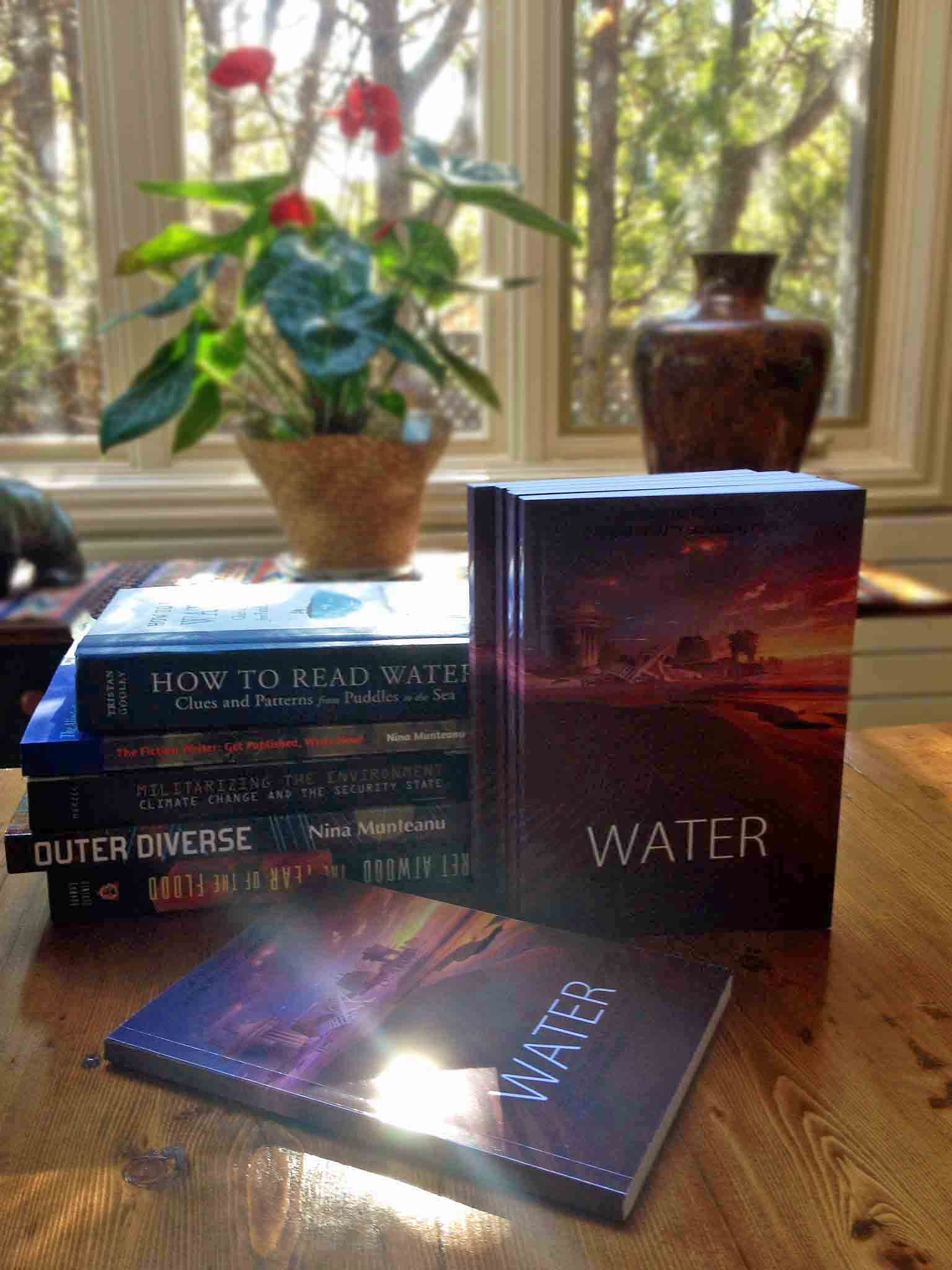

My desk with copies of “Water” among my current books to read…

The anthology features the art work of Digbejoy Ghosh (both cover and interior for each story) and stories by:

Holly Schofield

Michelle Goddard

Bruce Meyer

Robert Dawson

A.A. Jankiewicz

Costi Gurgu

You can buy a copy on Amazon.ca or through the publisher.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Every year, near Christmas,

Every year, near Christmas,  Margaret Atwood is a winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature as well as the Booker Prize (several times) and the Governor General’s Award. Animals and the environment feature in many of her books, particularly her speculative fiction, which reflects a strong view on environmental issues.

Margaret Atwood is a winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature as well as the Booker Prize (several times) and the Governor General’s Award. Animals and the environment feature in many of her books, particularly her speculative fiction, which reflects a strong view on environmental issues.

“

“ “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World” (Greystone Books) by Peter Wohlleben. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben shares his deep love of woods and forests and explains the amazing processes of life, death, and regeneration he has observed in the woodland and the amazing scientific processes behind the wonders of which we are blissfully unaware. Much like human families, tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, and support them as they grow, sharing nutrients with those who are sick or struggling and creating an ecosystem that mitigates the impact of extremes of heat and cold for the whole group. As a result of such interactions, trees in a family or community are protected and can live to be very old. In contrast, solitary trees, like street kids, have a tough time of it and in most cases die much earlier than those in a group. Drawing on groundbreaking new discoveries, Wohlleben presents the science behind the secret and previously unknown life of trees and their communication abilities; he describes how these discoveries have informed his own practices in the forest around him. As he says, a happy forest is a healthy forest, and he believes that eco-friendly practices not only are economically sustainable but also benefit the health of our planet and the mental and physical health of all who live on Earth.

“The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World” (Greystone Books) by Peter Wohlleben. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben shares his deep love of woods and forests and explains the amazing processes of life, death, and regeneration he has observed in the woodland and the amazing scientific processes behind the wonders of which we are blissfully unaware. Much like human families, tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, and support them as they grow, sharing nutrients with those who are sick or struggling and creating an ecosystem that mitigates the impact of extremes of heat and cold for the whole group. As a result of such interactions, trees in a family or community are protected and can live to be very old. In contrast, solitary trees, like street kids, have a tough time of it and in most cases die much earlier than those in a group. Drawing on groundbreaking new discoveries, Wohlleben presents the science behind the secret and previously unknown life of trees and their communication abilities; he describes how these discoveries have informed his own practices in the forest around him. As he says, a happy forest is a healthy forest, and he believes that eco-friendly practices not only are economically sustainable but also benefit the health of our planet and the mental and physical health of all who live on Earth. “Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants” (Ecco) by Richard Mabey. “They’re better for you than you think,” says Atwood. “They hold the waste spaces of the world in place, and you can eat some of them.” Ever since the first human settlements 10,000 years ago, weeds have dogged our footsteps. They are there as the punishment of ‘thorns and thistles’ in Genesis and , two millennia later, as a symbol of Flanders Field. They are civilisations’ familiars, invading farmland and building-sites, war-zones and flower-beds across the globe. Yet living so intimately with us, they have been a blessing too. Weeds were the first crops, the first medicines. Burdock was the inspiration for Velcro. Cow parsley has become the fashionable adornment of Spring weddings. Weaving together the insights of botanists, gardeners, artists and poets with his own life-long fascination, Richard Mabey examines how we have tried to define them, explain their persistence, and draw moral lessons from them. One persons weed is another’s wild beauty.

“Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants” (Ecco) by Richard Mabey. “They’re better for you than you think,” says Atwood. “They hold the waste spaces of the world in place, and you can eat some of them.” Ever since the first human settlements 10,000 years ago, weeds have dogged our footsteps. They are there as the punishment of ‘thorns and thistles’ in Genesis and , two millennia later, as a symbol of Flanders Field. They are civilisations’ familiars, invading farmland and building-sites, war-zones and flower-beds across the globe. Yet living so intimately with us, they have been a blessing too. Weeds were the first crops, the first medicines. Burdock was the inspiration for Velcro. Cow parsley has become the fashionable adornment of Spring weddings. Weaving together the insights of botanists, gardeners, artists and poets with his own life-long fascination, Richard Mabey examines how we have tried to define them, explain their persistence, and draw moral lessons from them. One persons weed is another’s wild beauty. “Birds and People” (Jonathan Cape) by Mark Cocker. “Vast, historical, contemporary, many-levelled,” says Atwood. “We’ve been inseparable from birds for millenniums. They’re crucial to our imaginative life and our human heritage, and part of our economic realities.” Vast in both scope and scale, the book draws upon Mark Cocker’s forty years of observing and thinking about birds. Part natural history and part cultural study, it describes and maps the entire spectrum of our engagements with birds, drawing in themes of history, literature, art, cuisine, language, lore, politics and the environment. In the end, this is a book as much about us as it is about birds.

“Birds and People” (Jonathan Cape) by Mark Cocker. “Vast, historical, contemporary, many-levelled,” says Atwood. “We’ve been inseparable from birds for millenniums. They’re crucial to our imaginative life and our human heritage, and part of our economic realities.” Vast in both scope and scale, the book draws upon Mark Cocker’s forty years of observing and thinking about birds. Part natural history and part cultural study, it describes and maps the entire spectrum of our engagements with birds, drawing in themes of history, literature, art, cuisine, language, lore, politics and the environment. In the end, this is a book as much about us as it is about birds.