In this series of articles, I draw from key excerpts of my textbook on how to write fiction The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now! whose 26 chapters go from A to Z on the key aspects of writing good and meaningful fiction.

G is for Defining your Genre & Going Beyond It

Although genres are not precisely definable, genre considerations are one of the most important factors in determining what a person will see or read. Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites.

For a long time people considered that books and movies that are difficult to categorize into a genre were likely to be less successful commercially. This is no longer the case, thanks to online bookstores like Amazon, that are able to ‘shelve’ books under multiple categories for people to find. In fact, having your book cross several genres (called “cross-genre” or slipstream) may even provide an advantage in that your book will occupy not just one but several niches—akin to placing your bets on several horses rather than just one.

So, if you haven’t figured out what genre your writing falls under, start figuring it out now; your future publisher and marketer will want to know because they, in turn, have to tell their distributor and bookseller where to shelve the book. This is why you need to do this, no matter what you think of categorizing your work; the alternative is leaving it to Jack in the marketing department who may not have even read your book, but used the cover picture to figure it out. Yikes!

The key to this exercise, whether your work falls under one or more categories, is to understand your work well enough to be able to categorize it. And, by all means, break the rules of categorizing—just know why you are.

H is for House or Home…Creating Memorable Settings

Setting fulfills most of the core aspects of a story. Without a place there is no story. Setting serves multipurpose roles from helping with plot, determining and describing character to providing metaphoric links to theme. Setting, like the force in Star Wars, provides a landscape that binds everything into context and meaning. Without setting, characters are simply there, in a vacuum, with no reason to act and most importantly, no reason to care.

Settings can not only have character; they can be a character in their own right. A novelist may often find herself, when portraying several characters, painting a portrait of place. This is setting being “character”. The setting functions as a catalyst, and molds the more traditional characters that animate a story. Think of any of your favourite books, particularly the epics: The Wizard of Oz, Tale of Two Cities, Doctor Zhivago, Lord of the Rings, The Odyssey, etc. In each of these books the central character is really the place, which is inexorably linked to its main character.

Settings depict the theme of your story through metaphor. The setting and all the objects in it are described to your reader through your POV character. This gives you an excellent opportunity to show the mood, temperament, judgment and bias of your character and their place in their world.

I is for Interviews and other Weird Experiences

As a writer of either fiction or non-fiction, you will at some time require information from a real person. Depending on the nature of your research and its intended destination and audience, you may wish to conduct anything from a casual phone or email enquiry to a full-blown formal face-to-face interview. This will also depend on who you are interviewing, from a neighbour to a government official. The pillars of good journalism include:

- thoroughness

- accuracy

- fairness and

- transparency.

Here are some tips on what to do:

- Do your research ahead of time: read up on your subject and include both sides of an issue (if that’s relevant). This helps you to respond intelligently with better follow-up questions.

- Ask open-ended questions: avoid yes and no questions and get them to elaborate. Asking “why” solicits explanation, which will give your article depth.

- Ask for examples: this provides a personal aspect to the article that gives it warmth and makes it more interesting.

- Ask personal questions: what’s the worst thing that can happen? They can simply say no; the up side is you may get a gem. The personal angle from the interviewee’s perspective gives your

- article some potential emotional aspect that gives it human-interest.

- Ask the interviewee for any further thoughts to share: it’s an innocuous question, but can offer-up more gems. What it provides you with is the possibility of getting something you might not have thought of, sparked by your conversation.

Here are some tips on what NOT to do:

- “There’s no rush.” Never reveal your deadline. Think about it; what do you normally do when there’s a deadline? Right…say it’s sooner than it really is.

- “I’ve never covered this topic before.” This kind of information is inappropriate and may make your interviewee uncomfortable (worrying about your unproven abilities to properly interview her instead of focusing on her). Besides, it’s not what you know but what you learn that counts.

- “I’ll be using what you say extensively.” Don’t assume and make promises you may not be able to keep, until after the interview.

- “I don’t get it.” If you don’t understand something, get clarification rather than make a negative remark that tends to stop them dead in their tracks.“You can review the piece before it’s published.” This is something that can be dealt with over the phone to confirm facts; the source doesn’t need to see the whole piece before it’s published.

- “This is going to be a fantastic article!” Keep your tone professional; there’s nothing wrong with being positive, but you should maintain a professional attitude that inspires confidence in the interviewee.

The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now! (Starfire World Syndicate) May 2009. Nominated for an Aurora Prix Award. Available through Chapters/Indigo, Amazon, The Book Depository, and Barnes & Noble.

The Fiction Writer is a digest of how-to’s in writing fiction and creative non-fiction by masters of the craft from over the last century. Packaged into 26 chapters of well-researched and easy to read instruction, novelist and teacher Nina Munteanu brings in entertaining real-life examples and practical exercises. The Fiction Writer will help you learn the basic, tried and true lessons of a professional writer: 1) how to craft a compelling story; 2) how to give editors and agents what they want; and 3) how to maintain a winning attitude.

“…Like the good Doctor’s Tardis, The Fiction Writer is larger than it appears… Get Get Published, Write Now! right now.”

David Merchant, Creative Writing Instructor

Click here for more about my other guidebooks on writing.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

This article is an excerpt from

This article is an excerpt from

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction. I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it.

I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it. Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility).

Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility). The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

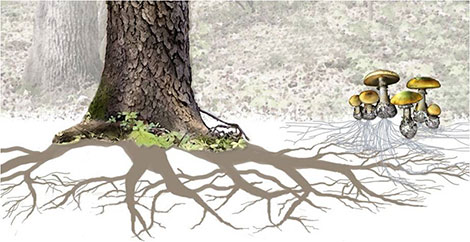

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  for its larvae. They do this by secreting a chemical that mimics how ants communicate; the ants in turn adopt the newly hatched caterpillars for two years. There’s a terrible side to this story of deception. The Ichneumon wasp, upon finding an Alcon caterpillar inside an ant colony, secretes a pheromone that drives the ants into confused chaos; allowing it to slip through the confusion and lay its eggs inside the poor caterpillar. When the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, the wasp eggs hatch and consume it from inside.

for its larvae. They do this by secreting a chemical that mimics how ants communicate; the ants in turn adopt the newly hatched caterpillars for two years. There’s a terrible side to this story of deception. The Ichneumon wasp, upon finding an Alcon caterpillar inside an ant colony, secretes a pheromone that drives the ants into confused chaos; allowing it to slip through the confusion and lay its eggs inside the poor caterpillar. When the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, the wasp eggs hatch and consume it from inside.

You can read more about this in my book “

You can read more about this in my book “ Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Use similes, metaphors, and personification to breathe life into setting

Use similes, metaphors, and personification to breathe life into setting