A worker tied to “the machine” in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

Our predictions and visions of the future are certainly predicated on our perceptions of the present and the past. So, what happens when yesterday’s “future” collides with today’s past? Well, retro-fiction, alternate history and steam-punk, you quip, eyes askance with mischief: edgy sociopathic Sherlock Holmes with bipolar or obsessive /compulsive tendencies; flying aircraft carriers in Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, robot-like workers of Metropolis…

Our predictions and visions of the future are certainly predicated on our perceptions of the present and the past. So, what happens when yesterday’s “future” collides with today’s past? Well, retro-fiction, alternate history and steam-punk, you quip, eyes askance with mischief: edgy sociopathic Sherlock Holmes with bipolar or obsessive /compulsive tendencies; flying aircraft carriers in Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, robot-like workers of Metropolis…

But what of the vision itself? History provides us with a panoply of realized predictions in speculative fiction:

In 1961, Stanislaw Lem’s novel Return From the Stars predicted the invention of the touch pad, iPhone, iPad and Kindle. The telescreens that monitored the citizens of George Orwell’s Oceania in his dystopian 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four was reflected, twenty years later, in the first closed circuit TV (CCTV) installed in the United Kingdom. Almost a century before the Internet was conceived, Mark Twain alluded to the future of a global, pervasive information network. In his 1968 novel 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke discussed a future where people scanned headlines online and got their news through RSS feeds. In his 1888 novel Looking Backward, Edward Bellamy describes a “future” society in 2000 where money is eliminated due to the proliferation of plastic credit cards. Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report accurately predicted personalized ads, voice-controled homes, facial and optical recognition, and gesture-based computing. Other advances and usage of technology have been predicted in speculative literature, including body scans, RFIDs, spy-surveillance, and touch screen interfaces.

Tom Cruise’s character using gesture-based computing in the film “Minority Report”

1950s ad for flying car of future

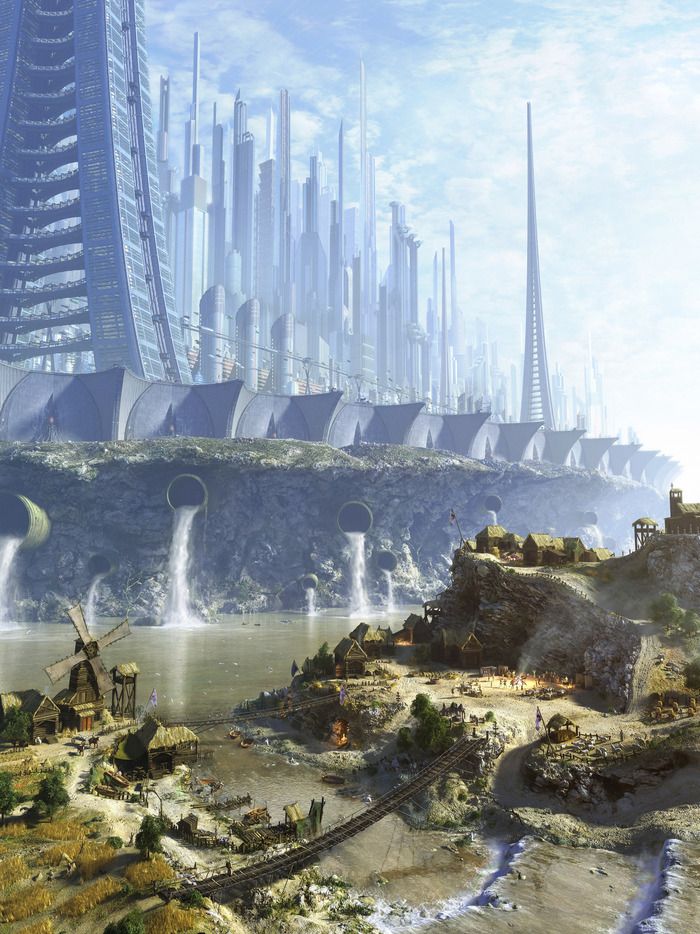

But there have been many speculations not realized. Where are the flying cars? Where are the moon colonies, rotating space stations and space elevator? What of the envisioned totalitarian states not realized; civilizations not demolished; utopias not developed?

Are those past dystopian or utopian visions failed attempts at predicting a future that eluded their writers? Or is it a question more of defining vision in speculative writing?

Ray Bradbury suggested that “the function of science fiction is not only to predict the future but to prevent it.”

There are, in most cases, no technological impediments to the flying car, the jetpack, and moon-bases; only cultural ones. “These SF predictions ought to be viewed as visions of where we could be, as opposed to where we will be, or, keeping Bradbury in mind, visions of where we don’t want to go and, thankfully, have mostly managed to avoid to date,” says Steve Davidson of Grasping for the Wind. “Perhaps it’s all cultural,” he adds.

There are, in most cases, no technological impediments to the flying car, the jetpack, and moon-bases; only cultural ones. “These SF predictions ought to be viewed as visions of where we could be, as opposed to where we will be, or, keeping Bradbury in mind, visions of where we don’t want to go and, thankfully, have mostly managed to avoid to date,” says Steve Davidson of Grasping for the Wind. “Perhaps it’s all cultural,” he adds.

How and why is it that our contemporary view of dystopian and utopian speculative fiction has shifted from an open-minded imaginative acceptance of “predictions” nested within a cautionary or visionary tale to a knowledge-based demand for largely unattainable predictive accuracy?

George Orwell wrote his dystopian satire in 1949 about a mind-controlled society in response to the Cold War. The book was a metaphor “against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism,” said Orwell in his 1947 essay Why I Write, adding, “Good prose is like a windowpane.” Was Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four a failed novel because the real 1984 didn’t turn out quite like his 1984? Hugo Award-winning novelist Robert J. Sawyer suggests that we consider it a success, “because it helped us avoid that future. So just be happy that the damn dirty apes haven’t taken over yet.”

George Orwell wrote his dystopian satire in 1949 about a mind-controlled society in response to the Cold War. The book was a metaphor “against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism,” said Orwell in his 1947 essay Why I Write, adding, “Good prose is like a windowpane.” Was Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four a failed novel because the real 1984 didn’t turn out quite like his 1984? Hugo Award-winning novelist Robert J. Sawyer suggests that we consider it a success, “because it helped us avoid that future. So just be happy that the damn dirty apes haven’t taken over yet.”

Dystopian and utopian literature, like all good allegory, provides us with scenarios predicated on a concrete premise. What if we kept doing this?…What if that went on unchecked?… What if we decided to end this?…

A hundred years before 1984, Edward Bellamy published Looking Backward, “a romance of an ideal world”. It tells the story of a young man who falls into a hypnotic sleep in 1887, waking up in 2000 when the world has evolved into a great socialist paradise. It sold over a million copies and ranked only behind Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ as the top best-seller of the era. Looking Backward laid out a futuristic socialism, or was it a socialistic future?

A hundred years before 1984, Edward Bellamy published Looking Backward, “a romance of an ideal world”. It tells the story of a young man who falls into a hypnotic sleep in 1887, waking up in 2000 when the world has evolved into a great socialist paradise. It sold over a million copies and ranked only behind Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ as the top best-seller of the era. Looking Backward laid out a futuristic socialism, or was it a socialistic future?

At any rate, it influenced a large number of intellectuals and generated an unprecedented political mass movement. The book spawned experiments in communal living and fed socialist movements that promoted the nationalization of all industry and the elimination of class distinctions. Bellamy’s book was cited in many Marxist polemic works. Groups all over the world praised and embraced its ideals: Crusading Protestant ministers, American feminists, Australian trade unionists, British town planners, Bolshevik propagandists, French technocrats, German Zionists, and Dutch welfare-state advocates.

Bellamy’s conviction that cooperation among humans is healthier than competition formed the basis of Looking Backward. He predicted a revolution in retail that resembled today’s warehouse clubs and big-box stores. He also predicted a card system much like a modern debit card and people using enhanced telephone lines to listen to shows and music.

“Socialism, of course, had different connotations in the 19th century when it rose, principally as a backlash to the brutalities of industrialization and the exploitation of the workers by the ruling class,” says Tony Long of Wired Magazine. Bellamy’s socialism is perhaps best described as a syndicalism than what most of us think of as socialism today. Long somberly adds, “Were he alive today, Bellamy might note, with interest, that while the worst excesses of the industrial age are gone, the exploitation continues. Had Bellamy lived to the ripe old age of 150, he no doubt would have been disappointed to find capitalism running amok, and his fellow man no less greedy and self-serving than in his own time. But he didn’t live to be 150. In fact, Bellamy was still a relatively young man when he died of tuberculosis in 1898.”

So, what happens when history catches up to the vision?

In a foreward to a later printing of Brave New World years after it was first published, Aldous Huxley explained why, when given the chance to revise the later edition, he left it exactly as it was initially written twenty years earlier:

In a foreward to a later printing of Brave New World years after it was first published, Aldous Huxley explained why, when given the chance to revise the later edition, he left it exactly as it was initially written twenty years earlier:

Chronic remorse, as all the moralists are agreed, is almost an undesirable sentiment. If you have behaved badly, repent, make what amends you can and address yourself to the task of behaving better next time. On no account brood over your wrongdoing. Rolling in the muck is not the best way of getting clean.

Art also has its morality, and many of the rules of this morality are the same as, or at least analogous to, the rules of ordinary ethics. Remorse, for example is as undesirable in relation to our bad art as it is in relation to our bad behavior. The badness should be hunted out, acknowledged and, if possible, avoided in the future. To pore over the literary shortcomings of twenty years ago, to attempt to patch a faulty work into the perfection it missed at its first execution, to spend one’s middle age in trying to mend the artistic sins committed and bequeathed by that different person who was oneself in youth–all this is surely vain and futile. And that is why this new Brave New World is the same as the old one. Its defects as a work of art are considerable; but in order to correct them I should have to rewrite the book–and in the process of rewriting, as an older, other person, I should probably get rid not only of some of the faults of the story, but also of such merits as it originally possessed. And so, resisting the temptation to wallow in artistic remorse, I prefer to leave both well and ill alone and to think about something else.

And with that, I leave you with a quote:

“…the past gives you an identity and the future holds the promise of salvation, of fulfillment in whatever form. Both are illusions.”–Eckhart Tolle

Snowing in New York City (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

We are now living in the Age of Water. Water is the new “gold”, with individuals, corporations and countries positioning themselves around this precious resource. Water is changing everything. The Age of Water Podcast covers anything of interest from breaking environmental news to evergreen material. This also includes human interest stories, readings of eco-literature, discussion of film and other media productions of interest.

We are now living in the Age of Water. Water is the new “gold”, with individuals, corporations and countries positioning themselves around this precious resource. Water is changing everything. The Age of Water Podcast covers anything of interest from breaking environmental news to evergreen material. This also includes human interest stories, readings of eco-literature, discussion of film and other media productions of interest. Proulx immerses the reader in rich sensory detail of a place and time, equally comfortable describing a white pine stand in Michigan and logging camp in Upper Gatineau to a Mi’kmaq village on the Nova Scotia coast or the stately Boston home of Charles Duquet. The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect and a fierce hunger for “more.”

Proulx immerses the reader in rich sensory detail of a place and time, equally comfortable describing a white pine stand in Michigan and logging camp in Upper Gatineau to a Mi’kmaq village on the Nova Scotia coast or the stately Boston home of Charles Duquet. The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect and a fierce hunger for “more.” “The reader comes to realize that the novel isn’t really about the human characters so much as it is about the forests,” Gus Powell of

“The reader comes to realize that the novel isn’t really about the human characters so much as it is about the forests,” Gus Powell of  In my recent novel

In my recent novel  The endocrine system is a set of glands and the hormones they produce that help guide and regulate the development, growth, reproduction and behavior of most living things (yes plants too!). Some hormones are also released from parts of the body that aren’t glands, like the stomach, intestines or nerve cells. These usually act closer to where they are released. The endocrine system is made up of glands, which secrete hormones, and receptor cells which detect and react to the hormones. Hormones travel throughout the body, acting as chemical messengers, and interact with cells that contain matching receptors. The hormone binds with the receptor, like a key into a lock. Some chemicals, both natural and human-made, may interfere with the hormonal system. They’re called endocrine disruptors.

The endocrine system is a set of glands and the hormones they produce that help guide and regulate the development, growth, reproduction and behavior of most living things (yes plants too!). Some hormones are also released from parts of the body that aren’t glands, like the stomach, intestines or nerve cells. These usually act closer to where they are released. The endocrine system is made up of glands, which secrete hormones, and receptor cells which detect and react to the hormones. Hormones travel throughout the body, acting as chemical messengers, and interact with cells that contain matching receptors. The hormone binds with the receptor, like a key into a lock. Some chemicals, both natural and human-made, may interfere with the hormonal system. They’re called endocrine disruptors.

My short story “Out of the Silence,” which appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of

My short story “Out of the Silence,” which appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of

In her 1997 biography Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, historian and science biographer Linda Lear wrote:

In her 1997 biography Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, historian and science biographer Linda Lear wrote:

“Miss Rachel Carson’s reference to the selfishness of insecticide manufacturers probably reflects her Communist sympathies, like a lot of our writers these days. We can live without birds and animals, but, as the current market slump shows, we cannot live without business. As for insects, isn’t it just like a woman to be scared to death of a few little bugs! As long as we have the H-bomb everything will be O.K.”

“Miss Rachel Carson’s reference to the selfishness of insecticide manufacturers probably reflects her Communist sympathies, like a lot of our writers these days. We can live without birds and animals, but, as the current market slump shows, we cannot live without business. As for insects, isn’t it just like a woman to be scared to death of a few little bugs! As long as we have the H-bomb everything will be O.K.”

Journalist, urbanist and futurist Greg Lindsay gave a rousing keynote speech to start the conference. Greg spoke about the future of cities, technology, and mobility. He is the director of applied research at NewCities and director of strategy at its mobility offshoot CoMotion. He also co-authored the international bestseller

Journalist, urbanist and futurist Greg Lindsay gave a rousing keynote speech to start the conference. Greg spoke about the future of cities, technology, and mobility. He is the director of applied research at NewCities and director of strategy at its mobility offshoot CoMotion. He also co-authored the international bestseller

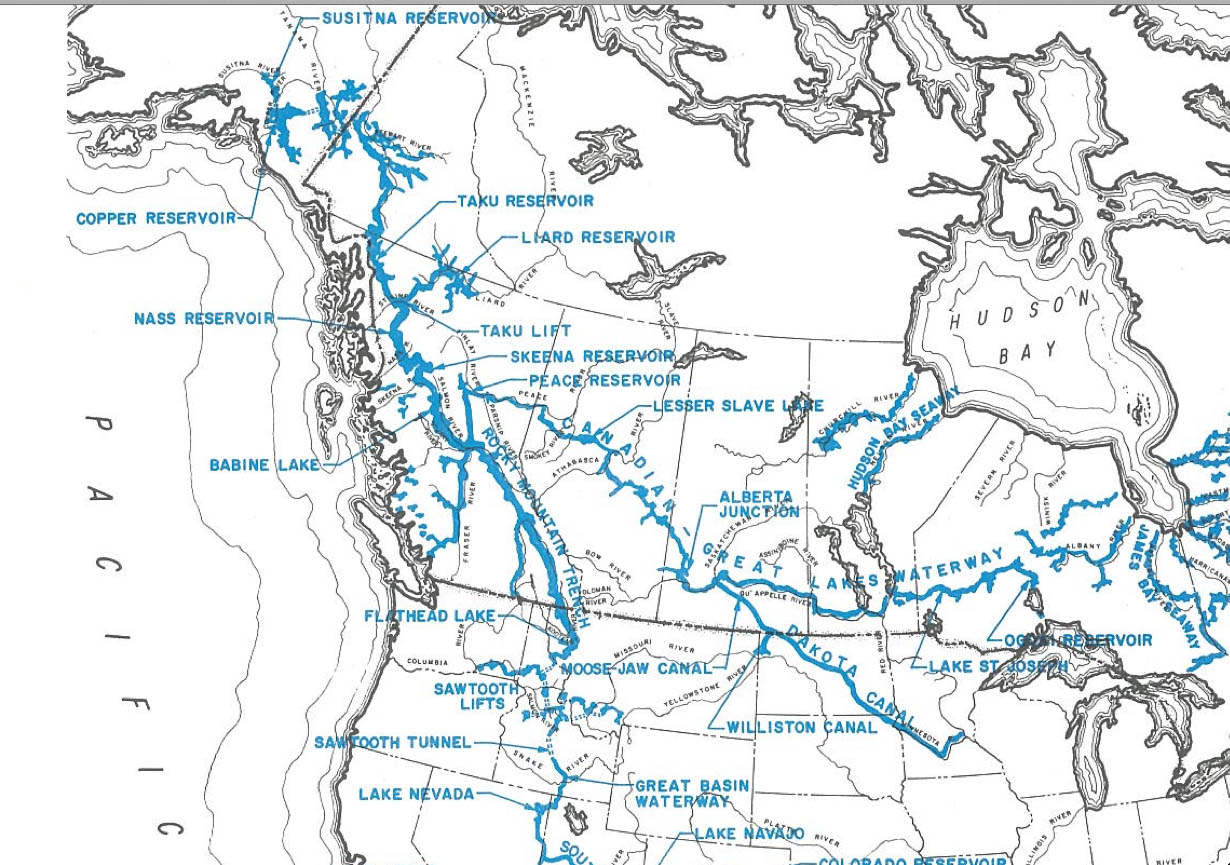

We then discussed future implications of water scarcity (and geopolitical conflict) and some of the things individuals and communities can do. Much of the talk drew from my recent book

We then discussed future implications of water scarcity (and geopolitical conflict) and some of the things individuals and communities can do. Much of the talk drew from my recent book  Craig Russell begins his eco-thriller Fragment with a TV interview of glaciologist Kate Sexsmith in Scott Base Antarctica. The interview is interrupted by what turns out to be four runaway glaciers that have avalanched into the back of the Ross Ice Shelf and a fragment the size of Switzerland surges out into the open sea. Hence the title: Fragment.

Craig Russell begins his eco-thriller Fragment with a TV interview of glaciologist Kate Sexsmith in Scott Base Antarctica. The interview is interrupted by what turns out to be four runaway glaciers that have avalanched into the back of the Ross Ice Shelf and a fragment the size of Switzerland surges out into the open sea. Hence the title: Fragment.

In my novel “

In my novel “

Both Daniels are talking about the alarming rate at which

Both Daniels are talking about the alarming rate at which  Research shows that consumption and/or exposure to many common constituents of urban living can decrease fertility, increase miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, and lower auto-immune systems. Examples include car exhaust, pesticides, common detergents, hair dyes, cleaning solvents, oil based paints, adhesives, gasoline; and consumption of MSG, coffee, alcohol.

Research shows that consumption and/or exposure to many common constituents of urban living can decrease fertility, increase miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, and lower auto-immune systems. Examples include car exhaust, pesticides, common detergents, hair dyes, cleaning solvents, oil based paints, adhesives, gasoline; and consumption of MSG, coffee, alcohol.

Leaning on his microscope, Daniel went on, “Wherever there’s a sewage treatment plant, pulp and paper mill, or herbicides and pesticides in a stream, you get endocrine disruption, which causes more female or intersex fish populations…[Degradation products of surfactants used in commercial and household detergents] inhibit breeding in male fish. And herbicides like atrazine—”

Leaning on his microscope, Daniel went on, “Wherever there’s a sewage treatment plant, pulp and paper mill, or herbicides and pesticides in a stream, you get endocrine disruption, which causes more female or intersex fish populations…[Degradation products of surfactants used in commercial and household detergents] inhibit breeding in male fish. And herbicides like atrazine—” Dr. Marilyn F. Vine at the University of North Carolina demonstrated that smoking men had lower sperm counts by 13-17%. Smokers also had more abnormal sperm. Likewise, women who smoked experienced more spontaneous abortions, early menopause and abnormal oocytes. Follicular fluid also contained high levels of cadmium, a heavy metal present in cigarettes, and cotininie, a metabolite of nicotine.

Dr. Marilyn F. Vine at the University of North Carolina demonstrated that smoking men had lower sperm counts by 13-17%. Smokers also had more abnormal sperm. Likewise, women who smoked experienced more spontaneous abortions, early menopause and abnormal oocytes. Follicular fluid also contained high levels of cadmium, a heavy metal present in cigarettes, and cotininie, a metabolite of nicotine.

In his book

In his book

For more on “ecology” and a good summary and description of environmental factors like aggressive symbiosis and other ecological relationships, read my book

For more on “ecology” and a good summary and description of environmental factors like aggressive symbiosis and other ecological relationships, read my book