Nina presents Diana Beresford-Kroeger with a copy of “Water Is…”

I recently participated in the 2018 Ontario Climate Symposium “Adaptive Urban Habitats by Design” at OCAD University in Toronto, hosted by the Ontario Climate Consortium and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority.

Day 1 opened with a ceremony by Chief R. Stacey Laforme of the Mississauga of the New Credit First Nation, followed by keynote address by Dr. Faisal Moola, associate professor of the University of Guelph.

A three-track panel stream provided diverse and comprehensive programming that helped further the goal to foster important discussions for how art and design can play a role in developing adaptive, low carbon cities. Panels sparked much networking among a diverse group of participants, who clustered around the refreshments in the Great Hall, where my “Water Is…” exhibit was located.

The Great Hall, where participants networked over refreshments

one participant clutches “Water Is…”

Water Is… was also there for sale, as part of my exhibit on water, along with Environment and Climate Change Canada, Green Roofs, Waste, and the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario. I had several lively and insightful conversations with participants and I’m glad to say that Water Is… made it into several people’s hands at the symposium. Water is, after all, a key component of climate and climate action.

The film “Call of the Forest: The Forgotten Wisdom of Trees” was screened and scientist Diana Beresford-Kroeger participated in a question and answer period then signed her latest book.

“Call of the Forest” was called “a folksy and educational documentary with a poetic sort of alarmism about disappearing forests,” by the Globe and Mail. The film “takes us on a journey to the ancient forests of the northern hemisphere, revealing the profound connection that exists between trees and human life and the vital ways that trees sustain all life on this planet.” The movie describes the numerous health-giving aerosols that trees use to communicate. Diana’s genuine and earnest concern illuminates her simple yet powerful narrative, such as when she says that the forests are “haunted by silence and a certain quality of mercy.” Featuring forests from Japan and Germany’s Black Forest to Canada’s boreal forest, this documentary is a powerful manifesto for sustainability.

Diana lecturing in High Park

On Day 2, I toured the Black Oak savanna in High Park with Diana Beresford-Kroeger (author of The Global Forest). The tour was refreshing and enlightening. Diana is a genuine advocate for the forest and showed some of the medicinal properties of forest plants. An example is the common weed, Goldenrod; its astringent and antiseptic qualities tighten and tone the urinary system and bladder, making goldenrod useful for UTI infections; Its kidney tropho-restorative abilities both nourishe and restore balance to the kidneys.

Diana spoke from the heart and brought a wealth of scientific knowledge to us in ways easy to understand—like the biochemistry of photosynthesis or quantum coherence. Diana shared how over 200 tree aerosols help combat anything from asthma to cancer. I also talk about this in the “Water Is Life” chapter of my book, Water Is…, which I gave a copy to Diana.

Shops in Lunenburg, NS (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

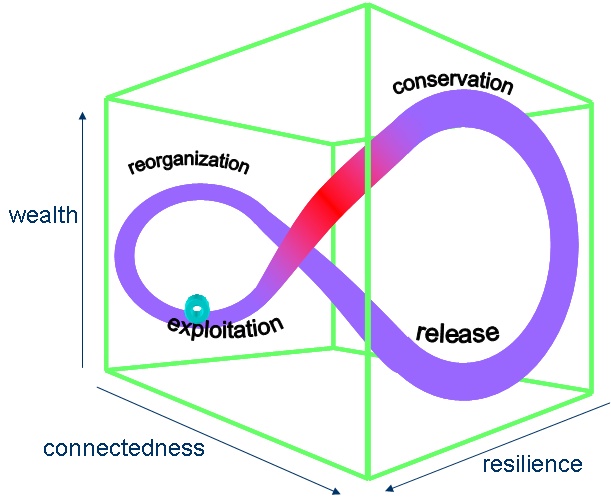

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In  In my speculative fiction novel,

In my speculative fiction novel,

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before;

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before; In my book

In my book

These weren’t ordinary ottomans—they were all animals! Hippos, bears, moose, elephants and pigs stood on stout legs, begging for a nice home to live in.

These weren’t ordinary ottomans—they were all animals! Hippos, bears, moose, elephants and pigs stood on stout legs, begging for a nice home to live in.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

J.K. Rowling was an unemployed single mother on public assistance when she wrote the first book. The book was rejected by over a dozen publishers before a small British publisher, Bloomsbury, said yes.

J.K. Rowling was an unemployed single mother on public assistance when she wrote the first book. The book was rejected by over a dozen publishers before a small British publisher, Bloomsbury, said yes. John Steinbeck worked through many odd jobs before earning enough to work as a full time writer. His day jobs included: apprentice painter, fruit picker, estate caretaker and Madison Square Garden construction worker. He also ran a fish hatchery in Lake Tahoe and did guided tours there.

John Steinbeck worked through many odd jobs before earning enough to work as a full time writer. His day jobs included: apprentice painter, fruit picker, estate caretaker and Madison Square Garden construction worker. He also ran a fish hatchery in Lake Tahoe and did guided tours there. Margaret Atwood worked in a coffee shop. She says her first job experience was NOT ideal: She had to deal with a difficult cash register, a rude ex-boyfriend who would come by just to stare at her and barely tip, and fellow employees who were definitely not friendship material.

Margaret Atwood worked in a coffee shop. She says her first job experience was NOT ideal: She had to deal with a difficult cash register, a rude ex-boyfriend who would come by just to stare at her and barely tip, and fellow employees who were definitely not friendship material. Before his writing career blossomed, William Faulkner worked for the postal service, as postmaster at the University of Mississippi. In his resignation note, he summarized the struggle of art and commerce faced by most authors: “As long as I live under the capitalist system I expect to have my life influenced by the demands of moneyed people. But I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp. This, sir, is my resignation.”

Before his writing career blossomed, William Faulkner worked for the postal service, as postmaster at the University of Mississippi. In his resignation note, he summarized the struggle of art and commerce faced by most authors: “As long as I live under the capitalist system I expect to have my life influenced by the demands of moneyed people. But I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp. This, sir, is my resignation.” In a 1953 interview, J.D. Salinger shared that he had served as entertainment director on the HMS Kungsholm, a Swedish luxury liner. He drew on the experience for his short story “Teddy”, which takes place on a liner.

In a 1953 interview, J.D. Salinger shared that he had served as entertainment director on the HMS Kungsholm, a Swedish luxury liner. He drew on the experience for his short story “Teddy”, which takes place on a liner. Ursula Le Guin struggled initially to be published in the mainstream fiction world, but her first three novels, Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions, put her on the sci-fi map.

Ursula Le Guin struggled initially to be published in the mainstream fiction world, but her first three novels, Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions, put her on the sci-fi map. An accomplished tenor, James Joyce made money singing for his supper before his work was published.

An accomplished tenor, James Joyce made money singing for his supper before his work was published. Harper Lee worked as a reservation clerk for Eastern Air Lines for several years, writing stories in her spare time. A windfall came when a friend offered her a Chirsmas gift of one year’s wages and one year off to write whatever she pleased; she wrote the first draft of “To Kill a Mockingbird”.

Harper Lee worked as a reservation clerk for Eastern Air Lines for several years, writing stories in her spare time. A windfall came when a friend offered her a Chirsmas gift of one year’s wages and one year off to write whatever she pleased; she wrote the first draft of “To Kill a Mockingbird”. Stephen King was a janitor for a high school as he struggled to get his fiction published. His time wheeling the cart through the halls inspired him to write the opening girl’s locker room scene in “Carrie”, his breakout novel.

Stephen King was a janitor for a high school as he struggled to get his fiction published. His time wheeling the cart through the halls inspired him to write the opening girl’s locker room scene in “Carrie”, his breakout novel. Kurt Vonnegut managed Americas first Saab dealership in Cape Cod during the late 1950s, a job he joked about in a 2004 essay, “I now believe my failure as a dealer … explains what would otherwise remain a deep mystery: why the Swedes have never given me a Nobel prize for literature.”

Kurt Vonnegut managed Americas first Saab dealership in Cape Cod during the late 1950s, a job he joked about in a 2004 essay, “I now believe my failure as a dealer … explains what would otherwise remain a deep mystery: why the Swedes have never given me a Nobel prize for literature.” When Virginia Woolf’s brilliant novels failed to find a publisher, she and her husband Leonard bought a printing press and set up their own publishing compay Hogarth Press in their living room. They published Woolf’s masterful novels, such as Orlando and To The Lighthouse, as well as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, among other classics of the era.

When Virginia Woolf’s brilliant novels failed to find a publisher, she and her husband Leonard bought a printing press and set up their own publishing compay Hogarth Press in their living room. They published Woolf’s masterful novels, such as Orlando and To The Lighthouse, as well as T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, among other classics of the era. T.S. Eliot worked as a clerk for Lloyds Bank of London. During that time, he composed “The Waste Land”.

T.S. Eliot worked as a clerk for Lloyds Bank of London. During that time, he composed “The Waste Land”. Franz Kafka served as the Chief Legal Secretary of the Workmen’s Accident Insurance Institute. Obviously.

Franz Kafka served as the Chief Legal Secretary of the Workmen’s Accident Insurance Institute. Obviously. and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams was no exception: At one point, he served as a bodyguard for a wealthy Arabian family while he wrote for radio shows and Monty Python. Good writers are good multitaskers!

and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams was no exception: At one point, he served as a bodyguard for a wealthy Arabian family while he wrote for radio shows and Monty Python. Good writers are good multitaskers! James A. Michener was a teacher before writing only at age 40. He Michener is notable more for his output than his age. The Tales of the South Pacific author (whose Pulitzer Prize-winning book would later be adapted into a Broadway musical) wrote a staggering 40 books after the age of 40—nearly a

James A. Michener was a teacher before writing only at age 40. He Michener is notable more for his output than his age. The Tales of the South Pacific author (whose Pulitzer Prize-winning book would later be adapted into a Broadway musical) wrote a staggering 40 books after the age of 40—nearly a  book a year—after spending much of his life as a teacher.

book a year—after spending much of his life as a teacher. Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  Nina Munteanu’s near-future speculative short story “The Way of Water” in Bruce Meyer’s (editor) “Cli Fi: Canadian Tales of Climate Change”, published by

Nina Munteanu’s near-future speculative short story “The Way of Water” in Bruce Meyer’s (editor) “Cli Fi: Canadian Tales of Climate Change”, published by  A bilingual print book by

A bilingual print book by  ” ‘The Way of Water’ is to be ‘a shapeshifter,’ says Nina Munteanu in her dystopian narrative, where she draws a dark scenario and, unfortunately, not too improbable in the near future. In the universe of the story water has become a very precious commodity: rationed consumption, credits (always of water) accounted for and debts collected…The Chinese multinationals have exchanged the public debt of other states with their water reserves with which, now, they can control the climate, deciding when and where it will rain. Who understands this dirty game has been silenced, like Hilda’s mother, a limnologist, inexplicably arrested and never returned; like the daughter of two water vendors, mysteriously disappeared, after having decided not to bow to economic powers: Hanna, who now prefers secure virtual identities to evanescent real appearances. Water. The two, like the covalent bond of a complex molecule, develop a relationship of attraction and repulsion that will first make them meet and then, little by little, will change into a tormented love but, at the same time, so pure as to cause Hilda at great risk, to make an extreme decision that will allow Hanna to realize the strange prophecy that the internal voice, perhaps the consciousness of water, had resonated in the two women for a long time.

” ‘The Way of Water’ is to be ‘a shapeshifter,’ says Nina Munteanu in her dystopian narrative, where she draws a dark scenario and, unfortunately, not too improbable in the near future. In the universe of the story water has become a very precious commodity: rationed consumption, credits (always of water) accounted for and debts collected…The Chinese multinationals have exchanged the public debt of other states with their water reserves with which, now, they can control the climate, deciding when and where it will rain. Who understands this dirty game has been silenced, like Hilda’s mother, a limnologist, inexplicably arrested and never returned; like the daughter of two water vendors, mysteriously disappeared, after having decided not to bow to economic powers: Hanna, who now prefers secure virtual identities to evanescent real appearances. Water. The two, like the covalent bond of a complex molecule, develop a relationship of attraction and repulsion that will first make them meet and then, little by little, will change into a tormented love but, at the same time, so pure as to cause Hilda at great risk, to make an extreme decision that will allow Hanna to realize the strange prophecy that the internal voice, perhaps the consciousness of water, had resonated in the two women for a long time. “The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s

“The Way of Water” will also appear alongside a collection of international works (including authors from Greece, Nigeria, China, India, Russia, Mexico, USA, UK, Italy, Canada (yours truly), Cuba, and Zimbabwe) in Bill Campbell and Francesco Verso’s