.

Twenty years ago, when I started seriously publishing short stories and novels, the environment was not recognized by the public or writers as an entity that deserved a literary category. Nature and environment were mostly portrayed and viewed as passive entities, to conquer, subdue, exploit and destroy at will (particularly in science fiction—with some notable exceptions such as The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury). Environment and Nature were not generally considered characters on a journey like the progatonist and other major characters; the environment lacked agency and was often ‘othered’ as dangerous, treacherous and unknowable.

Despite the fact that eco-fiction has in fact been in existence for centuries, use of this literary term is quite recent. Its first recognized use was in 1971, appearing as the title in John Stadler’s anthology published by Washington Square Press, which compiled environmental scifi works from the 1930s to the 1960s.

Defining Eco-Fiction

.

Author / scholar Mary Woodbury defines eco-fiction as “made up of fictional tales that reflect important connections, dependencies, and interactions between people and their natural environments.” In her article “Eco-Fiction—The SuperGenre Hiding in Plain Sight”, Judith defines eco-fiction as literature that “portrays aspects of the natural environment and non-human life as an evolving entity with agency in its relationship between and interaction with human characters.” In the preface to his 1995 book Where the Wild Boks Are: A field guide to Eco-Fiction, Jim Dwyer provides four criteria for eco-fiction:

- The nonhuman environment is present not merely as a framing device but as a presence that begins to suggest that human history is implicated in natural history

- The human interest is understood to be not the only legitimate interest

- Human accountability to the environment is part of the text’s ethical orientation

- Some sense of the environment as a process rather than as a constant or a given is at least implicit in the text.

These designations could be easily met by prehistoric cave art and first nations artwork and storytelling. These definitions also allow for the inclusion of many classics defined as eco-fiction from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native to John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids.

.

Evolving Eco-Fiction & Eco-SciFi

.

Like the environment it describes, Eco-Fiction is changing and evolving as a genre. Inventor/author Kyo Hwang Cho used the genre designation of Eco-SciFi when he recently identified me along with Kim Stanley Robinson, Jeff VanderMeer, and Richard Powers as Leading Voices in Eco-Science Fiction. Cho defines Eco-SciFi as: “a subgenre of SciFi that foregrounds ecological consciousness, blending speculative fiction with climate science, ethics, and planetary survival.” He includes a table that distinguishes Eco-SciFi from traditional Sci-Fi in several core areas from core theme, tone and motivation to protagonists and ‘message.’ The table can also be used to distinguish this sub-genre from other sub-categories within the umbrella term eco-fiction.

.

Cho described me as a Canadian ecologist and writer whose “stories explore how humans interact with the environment. Her narratives often examine the intersection of science, climate crisis, and spiritual transformation.” He described A Diary in the Age of Water as a noteworthy work of eco-science fiction: “a dystopian look at a future shaped by water scarcity, societal collapse, and ecological memory.”

.

Categories of Eco-Fiction

Partially due to this literature’s growing popularity there are currently many categories within and overlapping with eco-fiction; these include: climate fiction or clifi; solarpunk; eco literature, eco-horror, eco-punk, hopeful dystopia, mundane science fiction, speculative fiction, and weird fiction. Each of these focuses on particular idiosyncracies within the literary form that uniquely identify a work.

.

.

For instance, A Diary in the Age of Water has been variously described by reviewers and readers as eco-fiction, speculative fiction, science fiction or scifi, Fem-lit, mundane science fiction, hopeful dystopia, hopepunk or solarpunk, ecological science fiction or Eco-Sci-Fi. All to say that these designations and sub-genres are somewhat arbitrary and overlap; they may ultimately depend on the reader’s expectations of the work, and their own worldview and predilections. Given the still relevant reason for genre identification (to be able to best find the book in a brick and mortar or virtual bookstore), this makes sense; a work may easily satisfy several reader perspectives and therefore merit many sub-genre descriptors.

Eco-SciFi and mundane science fiction can be viewed this way. In an interview on Solarpunk Futures, I describe mundane science fiction as a sub-genre of science fiction that is very much like speculative fiction in that this sub-genre focuses on scenarios on Earth and involves matters to do with everyday life—hence the term mundane. Given the speculative aspect of mundane science fiction (e.g., set on Earth, often in the near-future), much of what Cho describes as Eco-SciFi also fits the designation of mundane science fiction. in my article “The Power of Diary in Fiction,” I describe Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, Emmi Itäranta’s Memory of Water and my own novel A Diary in the Age of Water as examples of mundane science fiction. Other good examples of mundane science fiction or Eco-SciFi include Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2041, Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s Bangkok Wakes to Rain and Michelle Min Sterling’s Camp Zero. These can all be labelled clifi as well. Min Sterling’s book also fits well under Femlit, Feminist Eco-Fiction, and Hopeful Dystopia.

The determining features provided by Cho that distinguish Eco-Sci-Fi help distinguish works that fall more easily into science fiction from those that better fit within the category of literary fiction or climate fiction.

Eco-Fiction—like Science Fiction—is a large category and provides a kind of umbrella term for all environmental fiction in which the environment plays a central role that informs the plot, theme and character-journey. In literature, it serves many literary works that do not include scifi aspects (e.g. fantastical or speculative); because of this, reserving the sub-genre of Eco-SciFi for those that do include fantastical elements makes sense. For non scifi works of Eco-Fiction, I would suggest using the term Eco-Lit (ecological literature), a term already in existence that incorporates the word ‘literature’ to suggest a type of literary fiction.

.

Ecological Literature or Eco-Lit

Eco-Lit—unlike Eco-SciFi—tends to restrict its narrative to the current time, does not include fantastical or speculative elements, and tends to use the ecological or climate elements more as metaphorical setting to examine personal drama. In all eco-fiction, however, the environmental setting/characteristic remains central to the story—as theme and/or premise— which would not work without it. Good examples of Eco-Lit include Migration and Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy, Flight Behavior and Prodigal Summer by Barbara Kingsolver, and Greenwood by Michael Christie. In each of these works, the environmental characteristic sparks, motivates, and helps direct the actions of the main protagonist. For instance, in Flight Behavior, if the protagonist Dellarobia Turnbow had not encountered the changed migration of the monarchs (as a result of climate change), she would not have taken a drastic turn in her own journey.

Thomas Hardy’s 1878 Return of the Native was a work of powerful literary eco-fiction (Eco-Lit) that gave Egdon Heath powerful agency over the other traditional characters: destroying, enabling, enlightening, strengthening, isolating.

.

Eco-Fiction as Hyperobject

Some have suggested that eco-fiction be considered a supergenre, given that it defies strict boundaries. Elements of eco-fiction can be found in many other genres, from romance or thriller to science fiction or historical, suggesting that it is more a state of being than a category with static boundaries; more like a door or a window than a room. In my opinion, eco-fiction encompasses more than a genre or category; it is a hyperobject that has been with us since storytelling was born. In his book Hyperobjects, philosopher Timothy Morton attempts to synthesize the still divergent fields of quantum theory (weirdness of tiny objects) and relativity (weirdness of large objects), inserting them into philosophy and art. According to Morton, a hyperobject is an entity that is massively distributed in space and time, making it difficult to grasp its totality or experience it as a single, unified object. Morton argues that the hyperobjects of the Anthropocene, such as global warming, climate or oil that have extensive time/space presence, have newly become visible to humans—mainly due to the very mathematics and statistics that helped to create these disasters. Glimpsing them through our copious data, hyperobjects “compel us to think ecologically, and not the other way around.”

.

I think that much of the fiction that authors write touches on climate and environment, whether they realize it or not, whether they are conscious of it or not. Climate and environment are both large, yet penetrating at the cellular level—influencing us in so many ways from obvious and literal to subtle and visceral. Try as we might—and we have for centuries tried—to separate ourselves and ‘other’ environment, we can’t escape it. “We are always inside an object,” says Morton. Hyperobjects show us that “there is no centre and we don’t inhabit it.”

.

I’ve created my own table, fashioned after Cho’s, and adapted to include Eco-Lit with pertinent examples:

| Categories of Fiction Genres Related to Ecology and Environment | |||

| SciFi | Eco-Fiction | ||

| Eco-SciFi | Eco-Lit | ||

| Setting | Science, technology, space, time travel, AI, aliens, etc.* driven by elements of science fact or fiction | Ecological systems, environmental collapse, climate change, sustainability.* Some element of science fact or fiction; speculative fiction | Ecological systems, environmental effects, climate change, sustainability |

| Tone | Often futuristic, space-based, dystopian, or technologically advanced societies* | Earth-centred or near-future settings deeply affected by ecological factors* | Earth-centred, mostly current settings, affected in some way by ecological factors; celebrates Nature in some way |

| Motivation | Curiosity, innovation, power struggles, survival in altered realities* | Preservation, adaptation, environmental justice, ethical stewardship* | Environmental awareness and action, human justice, introspection, reflection, identity |

| Story | Can be optimistic, dystopian, neutral, techno-utopian, or apocalyptic* often focussing on human justice, alternative civilizations; allegorical | Often cautionary, reflective, grounded in real world environmental urgency* often extrapolating into dystopian future, optimistic dystopia; metaphoric | Grounded in real and usually current world with undertones of environmental urgency, reflective, illuminating; literary |

| Protagonists | Scientists, explorers, rebels, AI, aliens, engineers* others | Environmentalists, ecologists, farmers, indigenous communities, climate activists* others connected to environment | Ordinary people, often linked in some intimate and actionable way to Nature |

| Examples | Dune (Herbert) I, Robot (Asimov) Neuromancer (Gibson) 1984 (Orwell) Brave New World (Huxley) The Martian Chronicles (Bradbury) Childhood’s End (Clarke) | The Ministry for the Future (Robinson) Annihilation (VanderMeer) A Diary in the Age of Water (Munteanu) The Windup Girl (Bacigalupi) Memory of Water (Itaranta) Waste Tide (Quifan) Camp Zero (Min Sterling) Bangkok Wakes to Rain (Sudbanthad) Lost Arc Dreaming (Okungbowa) | Flight Behavior (Kingsolver) Migration by (McConaghy) Greenwood (Christie) Barkskins (Proulx) The Overstory (Powers) Oil on Water (Habila) Where the Crawdads Sing (Owens) Return of the Native (Hardy) Moby Dick (Melville) |

| Message | Broad speculative insight into human potential* & survival, future tech, and evolution of civilization | Warns pf ecological degradation, offers alternative visions of coexistence* often through personal or community perspective | Exploration of the human spirit, growth and inspiration through personal environmental awareness and action |

| Structure | Often premise-based or plot-based; environment often ‘othered’ | Theme-based and character-based; environment often with agency | Character-based; environment may be metaphoric character with or without agency |

*descriptions taken directly from Cho’s article

.

References:

Morton, Timothy. 2013. “Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World.” University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. 240pp.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

“By failing to engage with climate change, artists and writers are contributing to an impoverished sense of the world, right at the moment when art and literature are most needed to galvanize a grassroots movement in favor of climate justice and carbon mitigation.”—Amitav Ghosh, 2017

“By failing to engage with climate change, artists and writers are contributing to an impoverished sense of the world, right at the moment when art and literature are most needed to galvanize a grassroots movement in favor of climate justice and carbon mitigation.”—Amitav Ghosh, 2017 What these novels have in common is that they are all

What these novels have in common is that they are all  According to Ghosh, plots and characters of contemporary literature tend to reflect the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depends on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature has been perceived as gradual (or static by some) and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely have been externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

According to Ghosh, plots and characters of contemporary literature tend to reflect the regularity of middle-class life and the worldview of the Victorian natural sciences, one that depends on a principle of uniformity. Change in Nature has been perceived as gradual (or static by some) and never catastrophic. Extraordinary or bizarre happenings were left to marginal genres like the Gothic tale and—of course—science fiction. The strange and unlikely have been externalized: hence the failure of modern novels and art to recognize anthropogenic climate change.

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.”

“To counteract this epidemic of short-term thinking,” says Fabiani, “it might be a good idea for more of us to read science fiction, specifically the post-apocalyptic sub-genre: that is, fiction dealing with the aftermath of major societal collapse, whether due to a pandemic, nuclear fallout, or climate change.” I recently shared a panel discussion with writer

I recently shared a panel discussion with writer  In 2015, I joined Lynda Williams of Reality Skimming Press in creating an optimistic science fiction anthology with the theme of water. My foreword to

In 2015, I joined Lynda Williams of Reality Skimming Press in creating an optimistic science fiction anthology with the theme of water. My foreword to

In my new writing guidebook

In my new writing guidebook

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In

Creative destruction … sounds like a paradox, doesn’t it? Nature—and God— is full of contradiction and paradox. There is so much that we do not understand (at least on the surface)… and apparent contradiction proves that to me. In  In my speculative fiction novel,

In my speculative fiction novel,

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before;

Suppression of spruce budworm populations in eastern Canada using insecticides partially protected the forest but left it vulnerable to an outbreak covering an area and of an intensity never experienced before; In my book

In my book

In a talk I give at conferences on “

In a talk I give at conferences on “ Terms such as

Terms such as  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the  Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions. Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

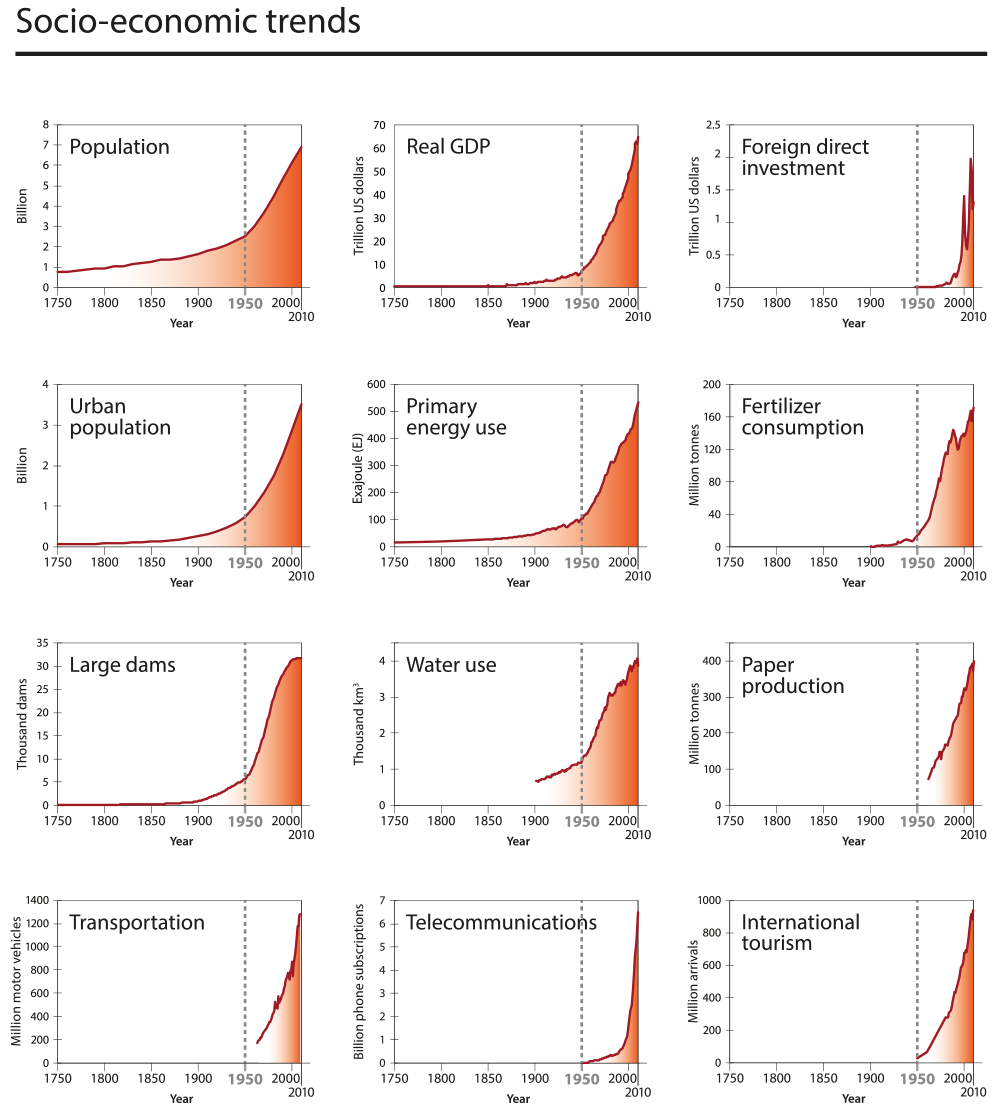

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II.

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II. The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society.

The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society. The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago.

The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago. In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’”

In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’” Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse.

Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse. Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking.

Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking. In my interview with Mary Woodbury on

In my interview with Mary Woodbury on  My own works of

My own works of  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit