In my article “Should You Judge a Book by its Cover”, I wrote about the importance of cover art for book sales and to maintain integrity and satisfaction with the story inside. In the article, I pointed out that, “If you don’t know the author of the book, the nature—and implied promise—of the cover becomes even more important. If the book does not deliver on the promise of the cover, it will fail with many readers despite its intrinsic value. A broken promise is still a broken promise. I say cover—not necessarily the back jacket blurb—because the front cover is our first and most potent introduction to the quality of the story inside. How many of us have picked up a book, intrigued by its alluring front cover, read the blurb that seemed to resonate with the title and image, then upon reading our cherished purchase been disillusioned with the story and decided we disliked it and its author?”

Liquid Silver’s romance / SF cover

Cover art provides an important aspect of writer and publisher branding. Cover artists understand this and address the finer nuances of the type and genre of the story to resonate with the reader and their expectations of story. This includes the image/illustration, typology, and overall design of the cover. A cover for a work of literary fiction will look quite different from a work of fantasy or romance. Within a genre, subtle qualities provide more clues—all of which the cover artist grasps with expertise.

I’ve been fortunate in my history as a professional writer to have had exceptional art work on the books I’ve written or collections and anthologies I’ve participated in (see the mosaic below of many but not all the covers my work has been associated with).

For most of my books, my publisher provided me with a direct link to the cover artist (e.g., Dragon Moon Press, Edge Publishing, eXtasy Books, Liquid Silver Books, Starfire, Pixl Press) and I retained some creative control. I even found and brought in the cover artist for two projects I had with Starfire.

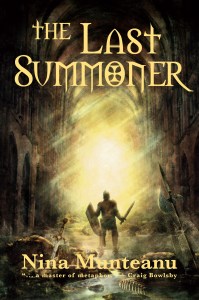

Tomislav Tikulin and “The Last Summoner”

Dragon Moon’s SF cover

Croation artist Tomislav Tikulin was the artist my Dragon Moon publisher had found for my 2007 book “Darwin’s Paradox”. For Darwin, I worked closely with Tikulin, who created the compelling hard science fiction cover of “future Toronto” that has attracted readers to the book for years. Tikulin has done cover designs for many publishers and bestselling writers from Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine and Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama to Amazing Stories Magazine.

Starfire’s fantasy cover

In perusing Tikulin’s website one day, I was transported by one of his illustrations—of an awestruck knight standing knee deep in a mire within a huge drowned cathedral. Shafts of golden light from the vaulted ceiling angled across, bathing the mire and the bemused knight beneath. There was a powerful story in that image, I thought, and wrote a whole book based on it: “The Last Summoner”. Imagine the feeling when I approached Tikulin to licence the image and then my Starfire publisher to use it—and both agreed! You’ll have to read the book to find out why the image was so important to the overall story. Graphic artist Costi Gurgu took Tikulin’s image and used his typology and design skills to create an extraordinary front and back cover and spine. You can learn more about Tikulin in my interview with him on The Alien Next Door.

Costi Gurgu and “The Splintered Universe Trilogy”

Starfire’s SF cover

I met Costi Gurgu and his wife Vali Gurgu at a science fiction convention in Montreal in 2009. Costi and Vali were successful graphic artists working on magazine covers and interiors for top magazines in Toronto. When I eventually moved there to teach at the University of Toronto, I discussed cover design with Costi. I was working on a detective thriller in space with kick-ass female detective and Galactic Guardian, Rhea Hawke. I’d initially envisioned the book as one entire novel with three parts, but it very soon became apparent to me that it was three actual books in a trilogy. The Splintered Universe Trilogy consists of Outer Diverse, Inner Diverse, and Metaverse.

I was intrigued by what Costi designed: a “Triptych” for the three books of The Splintered Universe Trilogy. In an interview I did on The Alien Next Door, I asked him what inspired him to come up with it and what did he like about it? Costi replied:

“Your main character, Rhea, undergoes a certain evolution from a regular human being to… let’s just say something else. And that evolution has three parts, one for each book of the trilogy and it also has a touch of divine. So, the triptych design, so often used for religious paintings, fits like a glove on the entire concept.”

Starfire’s SF cover

I was very taken by how the design for the triptych carried a powerful image that conjures a portal or gateway into another world (which is what the trilogy is about). The reader is drawn into an infinite landscape, looking in, and Rhea is looking out from within in Outer Diverse, bursting through in Inner Diverse, and walking outside with confidence in Metaverse. Costi explained the meaning behind the symbols and colours he used: “The initial idea was for the red ring to be a sort of mapping device and a radar combined into one, since Rhea travels great distances in her quest. Then I realized it might as well be a portal device on top of everything else and serve all her travelling needs.

There were two options —either we would look with her outside, to whatever target she had, or look towards her. I thought that it would be more powerful if we could look towards her and see her determined face, see the unflinching resolution in her eyes, while she’s pondering her next move and readying herself to use the device once again. But to look towards her and see her in a confining room of a space ship, or such, would have defeated the purpose. So, I needed to have her against the infinite landscape as the backdrop. She is in a continuous journey to discover herself and this journey takes her literally through the infinite spaces of not just one universe.”

Costi also shared some of the process in creating a cover design:

Starfire’s SF cover

“Technically speaking, I always start with sketches on paper, which I later scan. I mainly use Adobe Photoshop, but for this illustration I had to use Adobe Illustrator as well. Obviously, the layout and the typography were done in Adobe InDesign.”

Costi’s wife, Vali, was the model for Rhea Hawke. Some of the additional shoots can be seen in the Youtube book trailer). Costi shared that, “I had to decide how to treat her image. I could have gone towards a more glamorous, shiny look, like in a fashion image, or I could just simply keep it more realistic… I chose to keep it that way, because I wanted to offer a realistic image of an ex-police officer: a woman who was used to fighting and chasing criminals, rather than taking care of her appearance.”

You can read the complete interview with Costi on The Alien Next Door.

All Nina Munteanu books can be found on most Amazon sites.

Sampling of publication cover art for works by Nina Munteanu (to 2017)

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s recent book is the bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” (Mincione Edizioni, Rome). Her latest “Water Is…” is currently an Amazon Bestseller and NY Times ‘year in reading’ choice of Margaret Atwood.

I brought up the notion of history’s quantum properties, a braided flow of multi-dimensional and entangled realities. This served as premise for my alternative historical time-travel fantasy

I brought up the notion of history’s quantum properties, a braided flow of multi-dimensional and entangled realities. This served as premise for my alternative historical time-travel fantasy

Wonder Woman uses a unique weapon, the Golden Lasso, known as the Lasso of Truth—because it compels anyone wrapped by it to reveal the truth.

Wonder Woman uses a unique weapon, the Golden Lasso, known as the Lasso of Truth—because it compels anyone wrapped by it to reveal the truth.

In her book The Art of Slow Writing, Louise DeSalvo tells the story of how Ian McEwan composed his book Atonement.

In her book The Art of Slow Writing, Louise DeSalvo tells the story of how Ian McEwan composed his book Atonement.

I originally wrote the Paris section in Vivianne’s point of view, but it seemed flat with too obvious fish-out-of-water observations. I let the book sit, while I conducted more research on Paris, and then it came to me: give the narrative to François. This part of the book was his story. By giving François the only POV, I also gave his character agency to react and change to Vivianne’s role as “catalyst hero.” I rewrote this section, starting with François fleeing from a street crime he’d committed, when Vivianne literally appears and knocks him down. She then sweeps him up in a high-stakes chase that will change his worldview. When Vivianne returns to 1410 Poland in the last section of the book, her great journey of self-discovery and atonement begins.

I originally wrote the Paris section in Vivianne’s point of view, but it seemed flat with too obvious fish-out-of-water observations. I let the book sit, while I conducted more research on Paris, and then it came to me: give the narrative to François. This part of the book was his story. By giving François the only POV, I also gave his character agency to react and change to Vivianne’s role as “catalyst hero.” I rewrote this section, starting with François fleeing from a street crime he’d committed, when Vivianne literally appears and knocks him down. She then sweeps him up in a high-stakes chase that will change his worldview. When Vivianne returns to 1410 Poland in the last section of the book, her great journey of self-discovery and atonement begins. Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit