On Friday, June 9th, I drove with friend, songwriter and poet Honey Novick, to the 15th International Writers’ and Artists’ Festival in Val-David, Quebec (June 10th and 11th, 2017). Celebrated artists, poets, writers and singers with an international heritage that included France, Chile, Argentina, Romania, Canada and the USA would congregate at the festival, set in a large house nestled deep in the Maple Laurentian forest.

On Friday, June 9th, I drove with friend, songwriter and poet Honey Novick, to the 15th International Writers’ and Artists’ Festival in Val-David, Quebec (June 10th and 11th, 2017). Celebrated artists, poets, writers and singers with an international heritage that included France, Chile, Argentina, Romania, Canada and the USA would congregate at the festival, set in a large house nestled deep in the Maple Laurentian forest.

The mixed Laurentian forest is called the “eastern forest-boreal transition” and includes a varied tapestry of broadleaf (aspen, oak, paper birch, mountain ash and maple) and conifer (pine, spruce and fir) trees.

Nina Munteanu

When we reached our destination—a large three-story house surrounded by forest—I took in the aroma of fresh pine and “sweet fern” and spotted Bunchberry (soon to be designated Canada’s national flower), forget-me-nots and lupine carpeting the ground near the house. A young deer, foraging on a shrub’s new leaves beside the house, glanced at us without fear then slipped back into the forest.

I thought the setting ideal for an international festival celebrating the expression of the arts. I was scheduled to talk about my latest book “Water Is…”, a personal and scientific journey with water, and to give a lecture on eco-fiction.

View outside my bedroom

Flavia Cosma, the originator and organizer of the festival for over a decade, greeted us at the door and in true Romanian-fashion immediately sat us down to eat and drink. After a seven-hour drive (we somehow ended up in Charlamagne, Celine Dion’s birthplace), I was hungry and enjoyed some of Flavia’s signature dishes, varză a la Cluj (cabbage a la Cluj) and salată boeuf (beef salad), made with carrots, parsley roots, eggs, potatoes, beef, pickles and peas mixed with mayonnaise. The view outside my bedroom on the third floor peered through tall firs to a mountain valley and the small village of Val-David. I looked forward to meeting poets, writers, musicians and artists the next day…

Day 1: Saturday

Honey Novick

Honey Novick (Toronto, Ontario), poet laureate of the Summer of Love Project 2007 Luminato Festival and winner of the Bobbi Nahwegahbow Memorial Award, opened the festival with an inspirational song.

Composers and singers Brian Campbell (Montréal, Quebec) and Ivan-Denis Dupuis (Sainte Adele, QC) provided additional and stirring song performance.

Louis-Philippe Hebert

Quebec author Louis-Philippe Hébert (Saint Sauveur, QC), winner of the Grand Prix Québecor du Festival de Poésie de Trois-Rivières and the Prix du Festival de Poésie de Montréal, read from his novel Un homme discret (Lévesque, 2017). Poet Julie de Belle read several poems, including When the sea subsides, finalist in the Malahat Review. Brian Campbell, finalist in the 2006 CBC Literary Award for Poetry, read from his book Shimmer Report (Ekstasis Editions, 2015).

Flavia Cosma

Poet and award-winning TV documentarist Flavia Cosma, who received the gold medal as an honorary member by the Casa del Poeta Peruano, Lima, Peru in 2010, nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and whose work has been used in University of Toronto literature courses, read from her collection of poems, The Latin Quarter (MadHat Press, 2015) and Plumas de Angeles (Editorial Dunken, 2008).

Felicia Mihali

Romanian writer Felicia Mihali read from her novel La bien-aimée de Kandahar, nominated for Canada Reads 2013. Romanian author Melania Rusi Caragioiu, member of the Canadian Association of Romanian Writers, read from her book of poems Basm în versuri și poeme pentru copii in Romanian.

Nicole Davidson, the mayor of Val-David, read some of her poetry. Jeanine Pioger, French author of Permanence de l’instant, read a selection of her poetry. Jocelyne Dubois showed her artwork and Romanian artists Carmen Doreal and Eva Halus discussed their artwork and poetry.

“Water Is…”: I shared the inspiration and making of my latest book, “Water Is…”, a scientific study and personal journey as limnologist, mother, teacher and environmentalist, which was recently picked by Margaret Atwood in the NY Times as 2016 ‘Year in Reading’ and recommended by Water Canada as ‘Summer Reading’. I discussed how I first conceived the book as a textbook early in my career as a freshwater biologist and how it morphed from one idea into something completely different and why it is my most cherished work to date.

Day 2: Sunday

French poet David Brême gave a workshop on poetry and the cultural hybridization of franco-québécoise (atelier sur la poésie et l’hybridation culturelle franco québécoise), which he had given earlier in Toronto.

Nane Couzier

Montreal poet from France and Senegal, Nane Couzier, read from her collection Commencements, honorable mention in le Prix de poésie 2016 des Écrivains francophones d’Amerique.

Jocelyne Dubois

Novelist and short story writer Jocelyne Dubois read from her novel World of Glass, finalist for the 2013 QWF Paragraphe Hugh MaLennan Prize for fiction. Laurentian poet John Monette, author of the collection Occupons Montréal (Editions Louise Courteau, 2012) read several poems and Eva Halus, Romanian poet, read from her book Pour tous les Voyages. Chilean poet Tito Alvarado also read his poetry.

Claudiu Scrieciu of Nasul.TV Canada

Claudiu Scrieciu and Felicia Popa of Nasul.TV Canada—Televiziunea Libera—the Canadian chapter of Romanian TV in St. Laurent, Quebec, televised aspects of the festival and the closing ceremony. Felicia, who interviewed me for their show, talked with me about “Water Is…”.

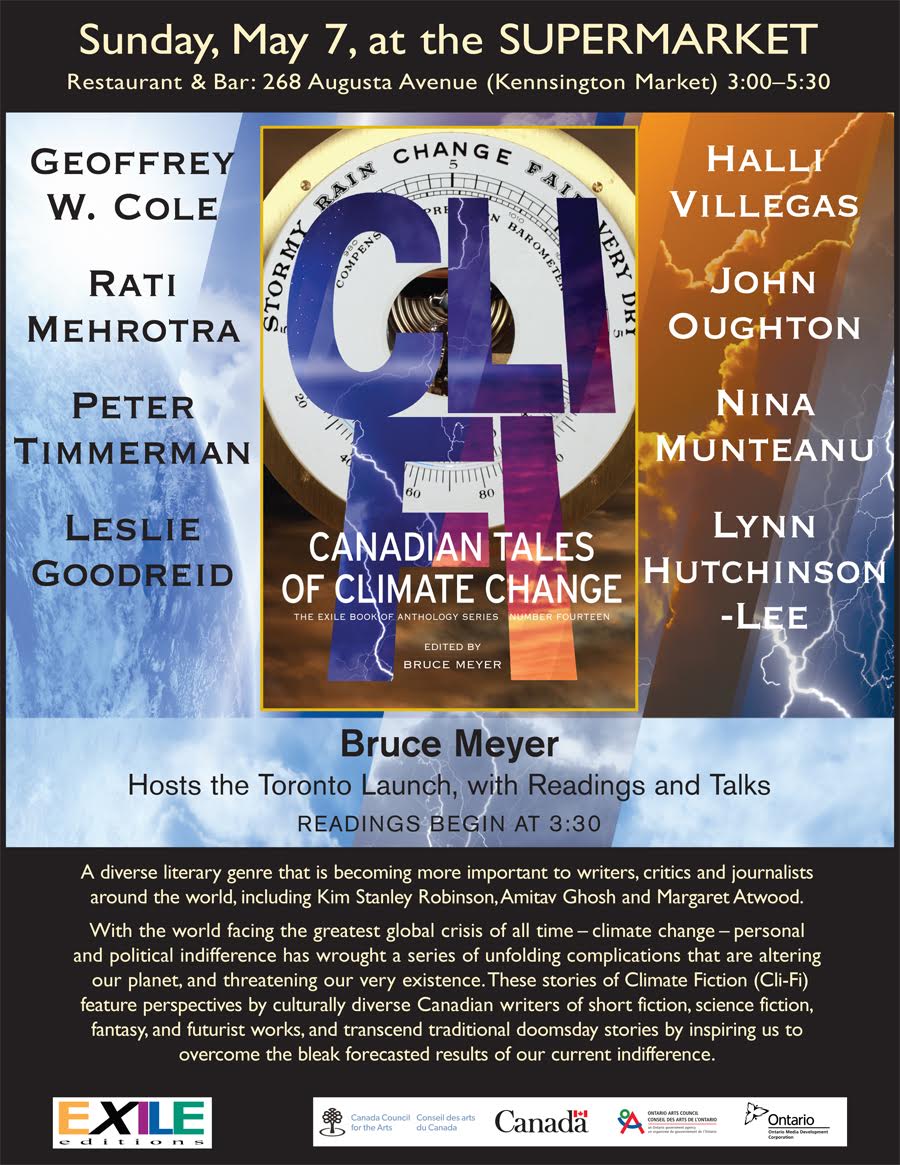

Eco-Fiction: I discussed how eco-fiction evolved as a genre and its importance, both metaphorically and literally, in the literature of the Anthropocene (with a nod to Margaret Atwood’s 2016 challenge to a college audience in Barrie, Ontario, to write the stories that focus on our current global environmental crisis). I provided examples of ecological metaphor such as Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Michael Ondaadje’s The English Patient, Frank Hebert’s Dune, and Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native. Astute questions, initiated by Flavia, led to an animated discussion on our ultimate participation in Nature, co-evolution, cooperation vs competition, soft-inheritance, DNA repair and the role and place of water in virtually all things.

The festival concluded at the Centre d’Exposition (art centre) of Val David with “Les Mots du Monde”, where poets, songwriters and writers performed readings and song to the community. The cultural setting and perfect acoustics provided a true inspiration for Honey Novick’s stirring opening songs—angelic in nature and in voice. I asked colleague Jeanine Pioger to read my essay “Why I Write,” which I had translated into French with help from colleague Betty Ing. The French version appears below.

Toasting the international festival

After the closing ceremony, Flavia invited participants to a grand dinner party at the festival house featuring authentic Romanian dishes, good wine and stimulating conversation.

The festival was a great success on many levels. Honey Novick astutely thanked Flavia in a Facebook post, “thanks for the wonderful memories, great inspiration, generous hearts and a tremendous weekend.” I felt a great resonance and synchronicity throughout the weekend. It was as though we all embarked on a dimensional ride together, orchestrated by Flavia, that challenged, fulfilled and enlightened…I spoke English, French and puțin limba română. Foarte puțin… …And the food… OOHLALA!

Mulțumesc, Flavia! A fost minunat!

La raison pour laquelle j’écris

L’écriture est le souffle et la lumière de mon âme et la source de mon essence. Quand j’écris, je vis le moment présent. Je suis dans le moment de la création, connecté au Soi Divin, embrassant la nature et l’ensemble de l’univers fractal.

Je fais quelque chose d’important.

Je me connecte avec vous.

Isaac Asimov a dit : « j’écris pour la même raison que je respire — parce que si je ne le faisais pas, je mourrirais ». C’était aussi vrai quand il était auteur inconnu qu’après qu’il est devenu grand écrivain. Il parlait métaphoriquement, spirituellement et littéralement. Je sais que si je n’écrivais pas, je me priverais mon âme de sa respiration de vie. Il représente plus que la vérité métaphorique ; il est scientifiquement prouvé. L’écriture expressive — que ce soit sous la forme de l’écriture d’un journal, de blogging, de l’écriture de lettres, de mémoires ou de fiction — améliore la santé.

Que vous publiiez ou non, votre écriture est importante et utile. Prenez possession de celle-ci, nourrissez-la et considérez-la comme sacrée. Inspirez le respect des autres et respectez tous les écrivains à leur tour ; ne laissez pas l’ignorance vous intimider et vous faire taire.

L’écriture, comme toute forme de créativité, exige un acte de foi ; tant en nous-mêmes qu’en les autres. Et c’est effrayant. C’est effrayant, parce qu’il faut que nous renoncions au contrôle. Il est d’autant plus préférable d’écrire. La résistance est une forme d’autodestruction, dit Julia Cameron, auteur de The Artist’s Way.

Nous résistons afin de maintenir une vague idée de contrôle, mais au contraire, nous augmentons nos chances de développer la dépression, l’anxiété et la confusion. Booth et al. (1997) ont conclu que la divulgation écrite réduit sensiblement le stress physiologique du corps causé par une inhibition. Nous sommes nés pour créer. Pourquoi hésitons-nous et résistons-nous? Parce que, dit Cameron, « nous avons accepté le message de notre culture… [que] nous sommes censés faire notre devoir et puis mourir. La vérité est que nous sommes censés être prospères et vivre ».

Joseph Campbell a écrit : « suivez votre bonheur et les portes s’ouvriront là où il n’y avait pas de portes avant. » Cameron ajoute : « c’est l’engagement interne pour être fidèle à nous-mêmes et de suivre nos rêves qui déclenche le soutien de l’univers. Alors que nous sommes ambivalents, l’univers nous semblera également être ambivalent et erratique. » Quand j’écris, je vis le moment présent, en harmonie avec le moment divin de la création.

En pleine joie.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

“Water, Abundance, Scarcity, and Security in the Age of Humanity” (NYU Press) by Jeremy Schmidt is an intellectual history of America’s water management philosophy. Debates over how human impacts on the planet, writes

“Water, Abundance, Scarcity, and Security in the Age of Humanity” (NYU Press) by Jeremy Schmidt is an intellectual history of America’s water management philosophy. Debates over how human impacts on the planet, writes  “A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change” (RMB Books) By Eileen Delehanty Pearkes reviews key historical events that preceded the Treaty, including the Depression-era construction of Grand Coulee Dam in central Washington, a project that resulted in the extirpation of prolific runs of chinook, coho and sockeye into B.C. Prompted by concerns over the 1948 flood, American and Canadian political leaders began to focus their policy energy on governing the flow of the snow-charged Columbia to suit agricultural and industrial interests.

“A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change” (RMB Books) By Eileen Delehanty Pearkes reviews key historical events that preceded the Treaty, including the Depression-era construction of Grand Coulee Dam in central Washington, a project that resulted in the extirpation of prolific runs of chinook, coho and sockeye into B.C. Prompted by concerns over the 1948 flood, American and Canadian political leaders began to focus their policy energy on governing the flow of the snow-charged Columbia to suit agricultural and industrial interests.  “Border Flows: A Century of the Canadian-American Water Relationship” (University of Calgary Press), Lynne Heasley and Daniel Macfarlane, editors, explore and discuss Canada-U.S. governance.

“Border Flows: A Century of the Canadian-American Water Relationship” (University of Calgary Press), Lynne Heasley and Daniel Macfarlane, editors, explore and discuss Canada-U.S. governance.  “New York 2140” (Orbit) by Kim Stanley Robinson is a novel set in New York City following major sea level rises due to climate change.

“New York 2140” (Orbit) by Kim Stanley Robinson is a novel set in New York City following major sea level rises due to climate change.  “The Death and Life of the Great Lakes” (WW Norton & Company Inc. Press) by Dan Egan is a frank discussion of the threat under which the five Great Lakes currently suffer. This book, writes

“The Death and Life of the Great Lakes” (WW Norton & Company Inc. Press) by Dan Egan is a frank discussion of the threat under which the five Great Lakes currently suffer. This book, writes  “Downstream: reimagining water” (Wilfred Laurier University Press) by Dorothy Christian & Rita Wong “brings together artists, writers, scientists, scholars, environmentalists, and activists who understand that our shared human need for clean water is crucial to building peace and good relationships with one another and the planet. This book explores the key roles that culture, arts, and the humanities play in supporting healthy water-based ecology and provides local, global, and Indigenous perspectives on water that help to guide our societies in a time of global warming. The contributions range from practical to visionary, and each of the four sections closes with a poem to encourage personal freedom along with collective care,” writes

“Downstream: reimagining water” (Wilfred Laurier University Press) by Dorothy Christian & Rita Wong “brings together artists, writers, scientists, scholars, environmentalists, and activists who understand that our shared human need for clean water is crucial to building peace and good relationships with one another and the planet. This book explores the key roles that culture, arts, and the humanities play in supporting healthy water-based ecology and provides local, global, and Indigenous perspectives on water that help to guide our societies in a time of global warming. The contributions range from practical to visionary, and each of the four sections closes with a poem to encourage personal freedom along with collective care,” writes  “

“

Water Canada

Water Canada

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction. I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it.

I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it. Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility).

Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility). The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

Early on in the recent science fiction movie Interstellar, NASA astronaut Cooper declares that “the world’s a treasure, but it’s been telling us to leave for a while now. Mankind was born on Earth; it was never meant to die here.” After showing Cooper how their last corn crops will eventually fail like the okra and wheat before them, NASA Professor Brand answers Cooper’s question of, “So, how do you plan on saving the world?” with: “We’re not meant to save the world…We’re meant to leave it.” Cooper rejoins: “I’ve got kids.” To which Brand answers: “Then go save them.”

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II.

“Scientists are telling us that the whole territory of modern history, from the end of World War II to the present, forms the threshold to a new geological epoch,” adds Jonsson. This epoch succeeded the relatively stable natural variability of the Holocene Epoch that had endured for 11,700 years. Scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer call it the Anthropocene Epoch. Suggestions for its inception vary from the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s with the advent of the steam engine and a fossil fuel economy to the time of the Great Acceleration—the economic boom following World War II. The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society.

The Great Acceleration describes a kind of tipping point in planetary change and succession resulting from a rising market society. The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago.

The Great Acceleration encompasses the notion of “planetary boundaries,” thresholds of environmental risks beyond which we can expect nonlinear and irreversible change on a planetary level. A well known one is that of carbon emissions. Emissions above 350 ppm represent unacceptable danger to the welfare of the planet in its current state; and humanity—adapted to this current state. This threshold has already been surpassed during the postwar capitalism period decades ago. In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’”

In Amitav Ghosh’s diagnosis of the condition of literature and culture in the Age of the Anthropocene (The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable), he observes that the literary world has responded to climate change with almost complete silence. “How can we explain the fact that writers of fiction have overwhelmingly failed to grapple with the ongoing planetary crisis in their works?” continues Jonsson, who observes that, “for Ghosh, this silence is part of a broader pattern of indifference and misrepresentation. Contemporary arts and literature are characterized by ‘modes of concealment that [prevent] people from recognizing the realities of their plight.’” Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse.

Jonsson tells us that bourgeois reason takes many forms, showing affinities with classical political economy, and—I would add—in classical physics and Cartesian philosophy. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity’s men have consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. When James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia Hypothesis in the 1970s, many saw its basis in a homeostatic balance of the natural order as confirmation of Nature’s infinite resilience to abuse. They failed to recognize that we are Nature and abuse of Nature is really self-abuse. Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking.

Louise Fabiani of Pacific Standard suggests that novels are still the best way for us to clarify planetary issues and prepare for change—even play a meaningful part in that change. In her article “The Literature of Climate Change” she points to science fiction as helping “us prepare for radical change, just when things may be getting too comfortable.” Referring to our overwhelming reliance on technology and outsourced knowledge, Fabiani suggests that “our privileged lives (particularly in consumer-based North America) are built on unconscious trust in the mostly invisible others who make this illusion of domestic independence possible—the faith that they will never stop being there for us. And we have no back-ups in place should they let us down.” Which they will—given their short-term thinking. In my interview with Mary Woodbury on

In my interview with Mary Woodbury on

Flight Behavior

Flight Behavior The Three Body Problem

The Three Body Problem Boiling Point

Boiling Point Quantum Night

Quantum Night Freenet

Freenet Silent Spring

Silent Spring Far from the Madding Crowd

Far from the Madding Crowd Martian Chronicles

Martian Chronicles Fahrenheit 451

Fahrenheit 451 Darwin’s Paradox

Darwin’s Paradox Night Country

Night Country Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek 2017 Novel & Short Story Writer’s Market

2017 Novel & Short Story Writer’s Market

Whether told through cautionary tale / political dystopia (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy; Bong Jung-Ho’s Snowpiercer), or a retooled version of “alien invasion” (e.g., Cixin Liu’s 2015 Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem), these stories all reflect a shift in focus from a technological-centred & human-centred story to a more eco- or world-centred story that explores wider and deeper existential questions. So, yes, science fiction today may appear less technologically imaginative; but it is certainly more sociologically astute, courageous and sophisticated.

Whether told through cautionary tale / political dystopia (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy; Bong Jung-Ho’s Snowpiercer), or a retooled version of “alien invasion” (e.g., Cixin Liu’s 2015 Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem), these stories all reflect a shift in focus from a technological-centred & human-centred story to a more eco- or world-centred story that explores wider and deeper existential questions. So, yes, science fiction today may appear less technologically imaginative; but it is certainly more sociologically astute, courageous and sophisticated. One of the lectures I give to my science fiction writing students is called “Ecology in Storytelling”. It’s usually well attended by writers hoping to gain better insight into world-building and how to master the layering-in of metaphoric connections between setting and character.1

One of the lectures I give to my science fiction writing students is called “Ecology in Storytelling”. It’s usually well attended by writers hoping to gain better insight into world-building and how to master the layering-in of metaphoric connections between setting and character.1 for its larvae. They do this by secreting a chemical that mimics how ants communicate; the ants in turn adopt the newly hatched caterpillars for two years. There’s a terrible side to this story of deception. The Ichneumon wasp, upon finding an Alcon caterpillar inside an ant colony, secretes a pheromone that drives the ants into confused chaos; allowing it to slip through the confusion and lay its eggs inside the poor caterpillar. When the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, the wasp eggs hatch and consume it from inside.

for its larvae. They do this by secreting a chemical that mimics how ants communicate; the ants in turn adopt the newly hatched caterpillars for two years. There’s a terrible side to this story of deception. The Ichneumon wasp, upon finding an Alcon caterpillar inside an ant colony, secretes a pheromone that drives the ants into confused chaos; allowing it to slip through the confusion and lay its eggs inside the poor caterpillar. When the caterpillar turns into a chrysalis, the wasp eggs hatch and consume it from inside.

You can read more about this in my book “

You can read more about this in my book “ Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel Flight Behavior was, according to

Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel Flight Behavior was, according to

Kathleen Byrne of The Globe and Mail

Kathleen Byrne of The Globe and Mail

We—humanity—may not be around here for much longer. Nature will endure without us. Planet Earth will continue, in some form and Nature and life will endure, evolve, and flourish—in its own way. It will change, perhaps grow more unruly than it is already, but Gaia will continue after she has kicked us off. Ecologists have long recognized the pattern of colonization, exploitation, decadence and succession. How hubristic of humanity not to include itself in that cycle. The cycle of continuing change. We grasp—we clamor—for the world we knew—even as we senselessly impose irreparable change. Shaving forests to the ground so water has no where else to go but down and in a torrent. Creating hot deserts by diverting great rivers somewhere else. Mining vast oil and mineral reserves by scraping the earth until it “bleeds” from unhealable wounds.

We—humanity—may not be around here for much longer. Nature will endure without us. Planet Earth will continue, in some form and Nature and life will endure, evolve, and flourish—in its own way. It will change, perhaps grow more unruly than it is already, but Gaia will continue after she has kicked us off. Ecologists have long recognized the pattern of colonization, exploitation, decadence and succession. How hubristic of humanity not to include itself in that cycle. The cycle of continuing change. We grasp—we clamor—for the world we knew—even as we senselessly impose irreparable change. Shaving forests to the ground so water has no where else to go but down and in a torrent. Creating hot deserts by diverting great rivers somewhere else. Mining vast oil and mineral reserves by scraping the earth until it “bleeds” from unhealable wounds.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps.

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps. After the release of the print book, Future Fiction released “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) in ebook format. The ebook contains the “Way of Water” story and another story, “Virtually Yours” (“Virtualmente tua”) alongside “The Story of Water” (non-fiction), which can be purchased in either Italian or Engish versions.

After the release of the print book, Future Fiction released “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) in ebook format. The ebook contains the “Way of Water” story and another story, “Virtually Yours” (“Virtualmente tua”) alongside “The Story of Water” (non-fiction), which can be purchased in either Italian or Engish versions.

Ebook (Italian OR English) with additional short story “Virtually Yours” through Future Fiction (Mincione Edizioni) for €1,99 at:

Ebook (Italian OR English) with additional short story “Virtually Yours” through Future Fiction (Mincione Edizioni) for €1,99 at: