Since “Expanse”, I’ve been on the lookout for an equally sophisticated treatment of space exploration—something that doesn’t slide into horrific mind-numbing and gut-wrenching insult to the senses, unrealistic character twists and visceral shock devices. Something that delivers…

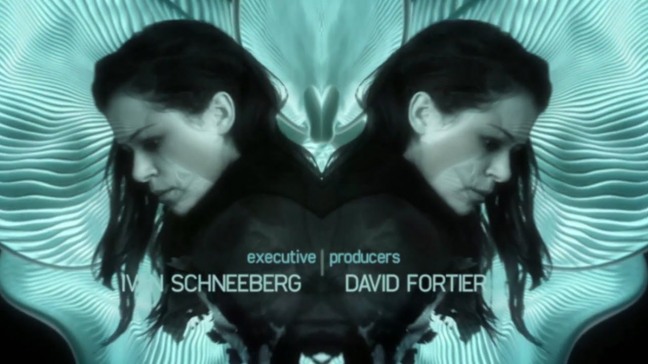

Season One of French TV series “Missions” has delivered in so many ways. Created by Henri Debeurme, Julien LaCombe and Ami Cohen, Season 1 (2017) of this series on the exploration of Mars has explored human evolution, ancient history, trans-humanism, artificial intelligence, and environmental issues in a thrilling package of intrigue, adventure and discovery. From the vivid realism of the Mars topography to the intricate, realistic and well-played characters and evocative music by Étienne Forget, “Missions” builds a multi-layered mystery with depth that thrills with adventure and complex questions and makes you think long after the show is finished.

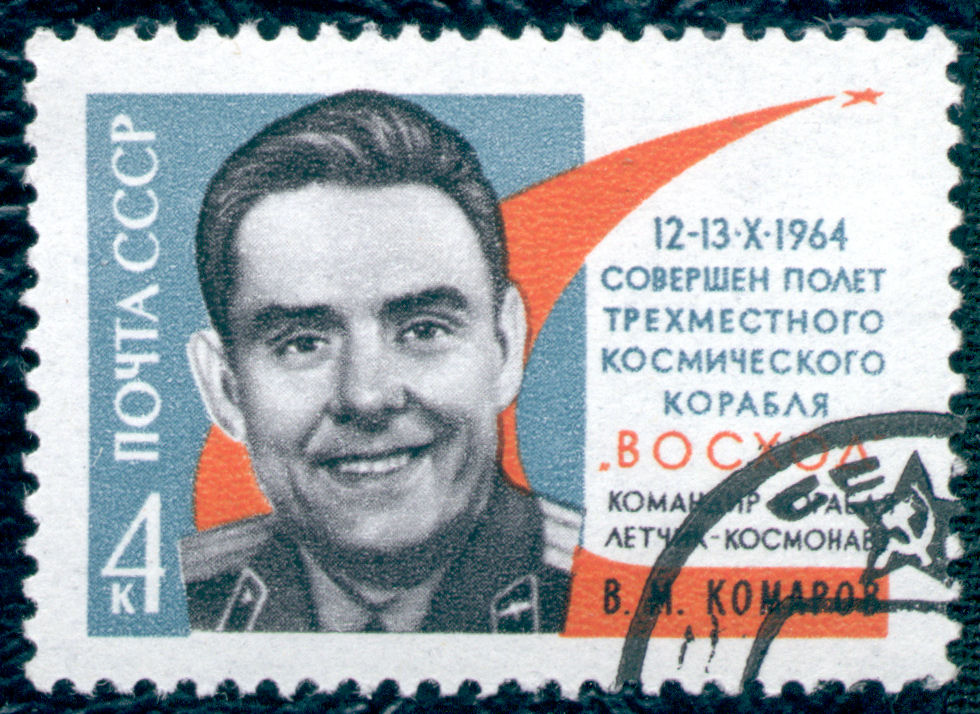

The first episode of the 10-episode Season One starts with a real tragedy: the first human to die in space flight; the 1967 fatal crash landing of the Russian Soyus 1 piloted by Cosmonaut Vladimir Komorov. In a stirring article on National Public Radio, Robert Krulwich provides incredible insight into this historic tragedy:

Starman by Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony, tells the story of a friendship between two cosmonauts, Vladimir Komarov and Soviet hero Yuri Gagarin, the first human to reach outer space. The two men were close; they socialized, hunted and drank together. In 1967, both men were assigned to the same Earth-orbiting mission, and both knew the space capsule was not safe to fly. Komarov told friends he knew he would probably die. But he wouldn’t back out because he didn’t want Gagarin to die. Gagarin would have been his replacement.

The story begins … when Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Soviet Union, decided to stage a spectacular mid-space rendezvous between two Soviet spaceships. The plan was to launch a capsule, the Soyuz 1, with Komarov inside. The next day, a second vehicle would take off, with two additional cosmonauts; the two vehicles would meet, dock, Komarov would crawl from one vehicle to the other, exchanging places with a colleague, and come home in the second ship. It would be, Brezhnev hoped, a Soviet triumph on the 50th anniversary of the Communist revolution. Brezhnev made it very clear he wanted this to happen.

The problem was Gagarin. Already a Soviet hero, the first man ever in space, he and some senior technicians had inspected the Soyuz 1 and had found 203 structural problems — serious problems that would make this machine dangerous to navigate in space. The mission, Gagarin suggested, should be postponed. The question was: Who would tell Brezhnev? Gagarin wrote a 10-page memo and gave it to his best friend in the KGB, Venyamin Russayev, but nobody dared send it up the chain of command. Everyone who saw that memo, including Russayev, was demoted, fired or sent to diplomatic Siberia.

With less than a month to go before the launch, Komarov realized postponement was not an option. He met with Russayev, the now-demoted KGB agent, and said, “I’m not going to make it back from this flight.” Russayev asked, Why not refuse? According to the authors, Komarov answered: “If I don’t make this flight, they’ll send the backup pilot instead.” That was Yuri Gagarin. Vladimir Komarov couldn’t do that to his friend. “That’s Yura,” the book quotes him saying, “and he’ll die instead of me. We’ve got to take care of him.” (italics mine).

In the opening scene of “Missions”, we never see the actual crash landing; instead, as Komarov hurtles to the ground, he suddenly sees a strange white light and then we cut to the present day. Now in an alternate present day, the international crew of the space ship Ulysses is readying for its journey to Mars. Days before the Ulysses mission takes off from Earth, psychologist Jeanne Renoir is asked to replace the previous psychologist who died suddenly in a freak accident.

We are introduced to Jeanne as she conducts a test at l’Université Paris with children on self-restraint using marshmallows. It’s a simple test: she leaves each child with one marshmallow and instructs that if they don’t eat it, she’ll give them a second one when she returns. Of course, the little girl can’t resist when left alone with the marshmallow and gobbles it down, giving up a second for her impatience. And we see that Jeanne correctly anticipates each child’s reaction.

Jeanne joins the international team of the Ulysses but maintains a detached relationship with them, refusing to get emotionally close to anyone; she cites her need as psychologist to remain impartial and objective and successfully hides a gentleness beneath an impenetrable layer of cold severity. The team consists of Captain Martin Najac and his estranged and depressed wife Alessandra (ship’s doctor), moody and laconic Simon Gramat (second in command), twitchy and paranoid Yann Bellocq (ship’s engineer), Basile (Baz), the sociopathic computer scientist who is more at ease with the ship’s AI Irène than the rest of the crew, and geologist Eva Müller, the target of Baz’s awkward advances.

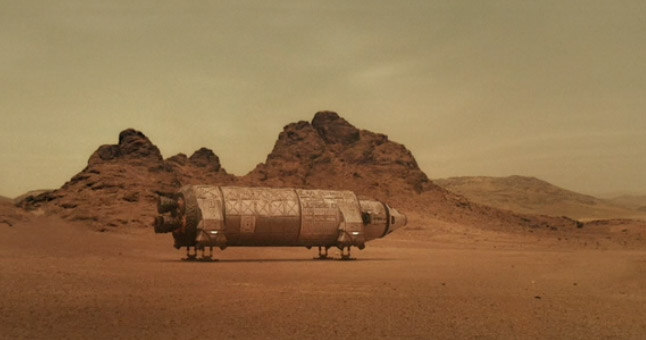

The eccentric Swedish corporate billionaire and David Bowie fan, William Meyer is also on board the Ulysses. His goal is to lead the first mission to land on Mars. However, shortly before they are scheduled to land, the crew discover that Z1—a ship sent by charismatic but highly unlikable Ivan Goldstein of rival corporation Zillion (partnered with NASA)—has overtaken them and has already landed on Mars. But the Z1 crew have not been heard from since sending a cryptic warning: “Don’t come here. Don’t try and save us… It’s too dangerous,” an intense Z1 astronaut warns.

After a rough landing through a major dust storm on Mars, the Ulysses crew struggle to fix an inoperable computer system (Irène) and life support system aboard their shuttle, which was presumably damaged by the landing. While not expecting to find any survivors of the Z1 crew, part of the Ulysses crew head to the Z1 landing site in a rover, looking for parts they can scavenge to power their shuttle. They find only remnants of the Z1 ship, but close by they discover someone alive in the Martian desert along with the ship’s black box. They presume he is from the American team but he insists that he is Russian and that his name is Vladimir Komarov…

So begins this surrealistic mystery that transcends history, identity and our concepts of reality with tantalizing notions of Atlantis, the mythical metal Orichalcum, programmable DNA-metal and much more. The first season of “Missions” focuses on cynical Jeanne Renoir as she unravels the mystery of Mars; a mystery that ties her inextricably to Komarov. When she first interviews Komarov, he surprises her by using her late father’s call to their favourite pastime of stargazing: “Mars delivers!” We then find that Komarov is her father’s hero for his selfless action to save his friend, and her father considered him “the bravest man of his time.” Jeanne is intrigued. Who—what—is this man they’ve rescued? Surely not the dead cosmonaut resurrected from 1967?

Throughout the series, choices and actions by each crew member weave narrative threads that lead to its overarching theme of self-discovery and the greater question of humanity’s existence. Yann Bellocq refuses to let the party who discovered Komarov back into the ship, citing oxygen depletion as his reason (“If you use oxygen to pressurize the airlock, you know what will happen. Better four survivors than eight corpses,” he says matter-of-factly as he dooms the four astronauts waiting to board). Eva later laments to Alex that “I thought I knew him.” Alex (who’s earlier terror had instigated the accidental death of her husband Captain Najac) tells Eva: “You’re young; there are situations which change people, for better or,” with a sideways glance at Bellocq, “worse.”

Intrigue builds quickly. By the third episode (Survivor), the crew make a startling discovery about Mars and humanity. After Komarov mysteriously leaves the ship and leads the small search party to a mysterious sentiently-created stone object, a stele, the ship’s computer Irène describes the hieroglyphs as ancient Earth-like. The main block, supported by four Doric columns is similar to the Segesta Temple in Sicily; its central designs are similar to Mayan Calakmul bas-reliefs; and its height-width ratio is equal to Phi, known as the golden ratio in ancient Greece.

Irène concludes that “either someone was inspired by our civilizations to build it…” “…Or our civilizations were inspired by it,” finishes Jeanne.

Alex, the ship’s doctor, informs the crew that the DNA of Mars-Komarov is identical to that of original-Komarov, except for an additional single strand; his DNA has three strands instead of two. She concludes, “He isn’t human.” Jeanne adds, “or he’s something more than human.” They also discover that the stone stele is actually an artificial alloy not known in any geology database but described in ancient script as the mythical substance ancient Greek and Roman texts called Orichalcum—the metal of Atlantis. Irène also identifies similar triple helix DNA in the rock, similar to Komarov’s, that is data-processing—which makes Komarov a living computer program, capable of controlling the ship.

Jeanne later confronts Komarov about the stone object; stating the need for expediency, she asks him what he meant to show them by leading them there. After telling her that humans need to discover truths for themselves before accepting them, Komarov slides into metaphor that reflects her previous psychology experiments on restraint and patience: “Imagine that your right hand holds all the answers about me and your left hand holds all the answers about you, Mars, and the universe. If you open your right hand, the left disappears.” Jeanne quips back, “I’d open the left first.” Komarov rejoins, ”That would be too easy. Some rules can’t be broken. Making a choice means giving something up.” She must wait before she can open her left hand. Like the child and the second marshmallow…

From the beginning, we glimpse a surreal connection between Jeanne and Komarov and ultimately between Earth and Mars: from her childhood admiration for the Russian’s heroism on Earth to the “visions” they currently share that link key elements of her past to Mars and Komarov’s strange energy-giving powers, to Jeanne’s own final act of heroism on Mars. “You’re the reason I’m here,” he confesses to her in one of their encounters. “You have an important decision to make; one you’ve made in the past…”

As the storyline develops, linking Earth and Mars in startling ways, and as various agendas—personal missions—are revealed, we finally clue in on the main question that “Missions”—through the actions of each crew member and the exchanges between Komarov and Jeanne—is asking: are we worth saving?

In a flashback scene of her interaction with Komarov, Jeanne recalls Komarov telling her that, “people dream of other places, while they can’t even look after their own planet… You must remember your past in order to think about your future. Do you think Earth has a future?” When she responds that she doesn’t know, he challenges with “Yes, you do. They eat their marshmallow right away, when they could have two…Or a thousand. Do you think humanity can continue like that? You know the answer and it terrifies you.”

In the sixth episode (Irène), Jeanne pieces together a complex scenario from her encounters with Komarov, compelling her to leave the ship to discover more.

Fearing for her safety and spurred on by a frank discussion with Komarov who recognizes how much Gramat cares for Jeanne (“You’re an impulsive man, especially when you talk about her…She’s counting on you, even if she’s too proud to say so”), Gramat pursues her on the surface of Mars. It is the first of two times that he will save her life, the second by using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. After they appear to cross a time-space portal, Komarov is waiting for them and the two astronauts learn Mars’s greatest secret: it was green and inhabited once, a very long time ago, by Martians who destroyed it then colonized Earth. Jeanne learns that she is an “evolutionary accident”: “You alone can save them … from themselves…or not,” says Komarov. She must return to Earth, he tells her, despite their ship not having enough fuel to get them off Mars.

Even after Zillion’s second ship, Z2, lands on Mars, giving the Ulysses crew a possible way off the planet, by season-end (Episode 10, Storm), it doesn’t look like Jeanne will leave Mars as the Ulysses crew meet with resistance from the other crew and a sudden storm surges toward them. Even if she does, will she return to save humanity or deliver them to their end? We’re not sure as we watch the ship take off with her still standing on Mars after dispatching their last impediment–one of the Z2 crew wishing to stop them. But she is not the same Jeanne we first met in episode one as she assures Gramat that she has no regrets—except for one (him, obviously). She follows with, “Let’s say you gave me the kiss of life…”

On to Season Two for more answers, and probably more questions…

The Lore—and the Lure—of Mars

When I was a child, my older brother told me that my parents found me in the huge garden behind our house and they brought me home out of pity. I scoffed back: ‘no, I wasn’t,’ I said with great confidence. I’d come down from Mars to study humans, I pronounced. I was born in April, after all; I’m an Aries and Mars is my planet.

Ancient Observations of Mars

In ancient times of Mars observation (before 1500) little was known about it except that it appeared as a fiery red star and followed a strange loop in the sky, unlike other stars. In Roman myth, Mars was a fierce warrior god, protector of Rome, with the wolf his symbol. To the Greeks, Mars was Ares and that’s what they named the star (planet). The Babylonians, who studied astronomy as early as 400 BC, called Mars Nergal, the great hero, the king of conflicts. The Egyptians noticed that five bright objects in the sky (Mercury, Mars, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn) moved differently from the other stars. They called Mars Har Decher, the Red One.

Mars in the 1600s and 1700s

In 1609 Johannes Kepler, a student of Tycho Brahe, published Astonomia Nova, which contained his first two laws of planetary motion. His first law assumed that Mars had an ellipitical orbit, which was revolutionary at the time. Then Galileo Galilei made the first telescopic observation of Mars in 1610 and within a century astronomers discovered distinct albedo features on the planet, including the dark patch Syrtis Major Planum and polar ice caps. They also determined the planet’s rotation period and axial tilt.

In 1659 Dutch astronomer Christian Huygens made the first useful sketch of Mars using an advanced telescope of his own design. He recorded a large dark spot or maria (probably Syrtis Major) and noticed that the spot returned to the same position at the same time the next day, which made him conclude that Mars had a 24 hour period. He later observed a white spot, likely the southern polar cap and likely assumed it was made of snow, ice or both. Huygens believed that Mars might be inhabited, perhaps even by intelligent creatures, and shared his belief with many other scientists. Giovanni Cassini later confirmed the polar caps and his nephew Giacomo Filippo Maraldi speculated that their changes showed evidence of seasons. In 1783, William Herschel confirmed that Mars experienced seasons; he is thought to be the first person to use the term “sea” for maria, though he was not the first to assume that maria actually contained liquid water. In 1860, Emmanuel Liais suggested that the variations in surface features were due to changes in vegetation (not flooding or clouds). Indeed, Father Pierre Angelo Secchi noticed in 1863 that maria changed colour, showing green, brown, yellow and blue.

The (In)Famous Canals of Mars

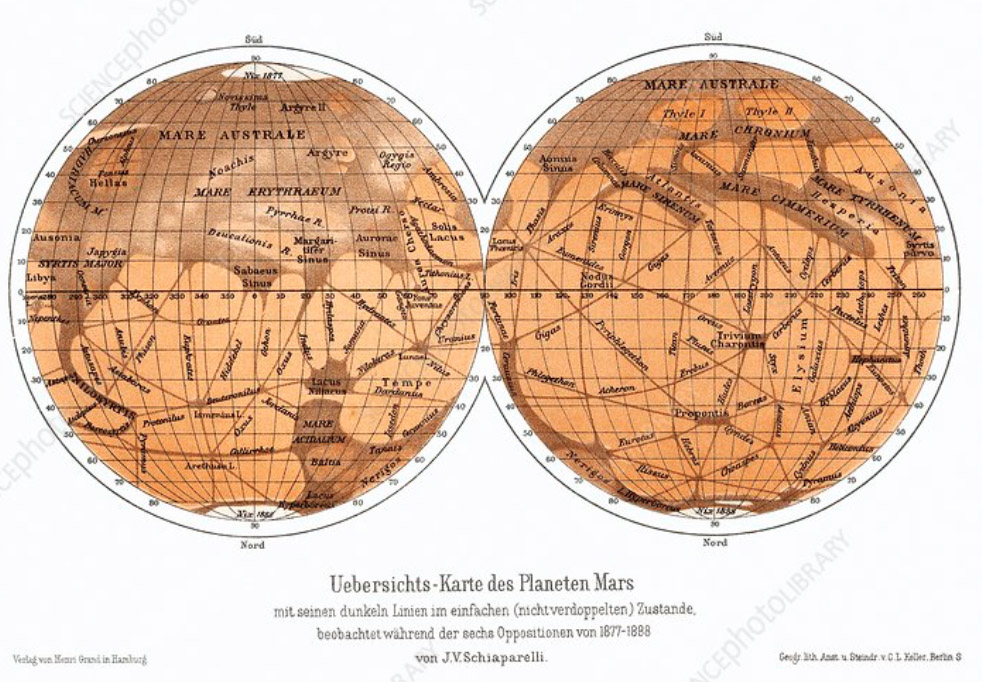

In the 1880s Giovanni Schiaparelli made a map of Mars that showed maria, but also connected by thin lines. He assumed the lines were natural landscape features and called them “canali,” which is Italian for “groove.” Translated into English it became “canal,” meaning something entirely different and opening speculation about an intelligent civilization on Mars. French astronomer Camille Flammarion wrote a book on Mars, suggesting that these canals might be signs of intelligent life.

Although Edward Emerson Barnard observed craters on Mars in 1892 (which suggested a lack of protective atmosphere and unlikely vibrant civilization there), public attention remained on the Martian canals, primarily through Percival Lowell’s efforts. His 1907 book “Mars and its Canals,” which suggested that the canals were built by Martians to transport water from the poles to the dry Martian plains, was widely read and embraced by a humanity eager for romantic adventure. That same year Alfred Russel Wallace (yes, the same scientist who came up with the theory of evolution based on natural selection before Darwin published On the Origin of Species, receiving full credit for its development) made a sound rebuttal with his own book that argued that Mars was completely uninhabitable; Wallace used measurements of light coming from Mars and argued that its surface temperature of minus 35 degrees Fahrenheit precluded the existence of liquid water. He also concluded correctly that the polar caps were frozen carbon dioxide, not water ice. But it didn’t matter; Wallace seemed doomed to be ignored, again… The idea of intelligent Martian life endured. The canal controversy was finally resolved in the 1960s with incontrovertible proof delivered by photographs taken by spacecraft on flybys or orbits around Mars. Mariner 4. Viking series. Pathfinder, the Mars Global Surveyor and Odyssey.

Mars in Literature and Film

Edgar Rice Burrough’s Barsoom series continued the romantic portrayal of Mars with its canals.And, of course a long tradition of portraying Martians as evil warmongering types is typified in the 1938 radio production by Orson Wells of the H.G. Wells 1897 work of fiction War of the Worlds, a story of Martians invading the Earth. The production was so convincing, that it set off a panic. In the 1940s Ray Bradbury wrote The Martian Chronicles, a poetic satire about humanity’s colonization of Mars and our inevitable destruction of its indigenous inhabitants–but not before the Martians attacked the settlers with their only weapon: telepathy. In the 1950 film Rocketship X-M, Martians are disfigured cave people who inhabit a barren wasteland, descendants of a nuclear holocaust. Martians have been depicted in various ways: enlightened and superior by Kurd Lasswitz in the 1897 novel Auf zwei Planeten, where the Martians visit Earth to share their more advanced knowledge with humans and gradually end up acting as an occupying colonial power. The 1934 short story “A Martian Odyssey” by Stanley G. Weinbaum describes the first ‘alien aliens’ in science fiction. The story broke new ground in portraying an entire Martian ecosystem unlike that of Earth—inhabited by species that are alien in anatomy and inscrutable in behaviour—and in depicting extraterrestrial life that is non-human and intelligent without being hostile. Several stories after the various Mariner and Viking probes had visited Mars, focused on its lifeless habitat and attempts to colonize it. The disappointment of finding Mars to be hostile to life is reflected in the 1970 novel Die Erde ist nah (The Earth is Near) by Ludek Pesek, which depicts members of an astrobiological expedition on Mars driven to despair by the realization that their search for life there is futile.

The theme of terraforming Mars later became prominent in the latter part of the 20th century, exemplified by Kim Stanley Robinson’s 1990s Mars Trilogy. The Expanse books and TV series portrays humans who have colonized Mars and in the process of terraforming it.

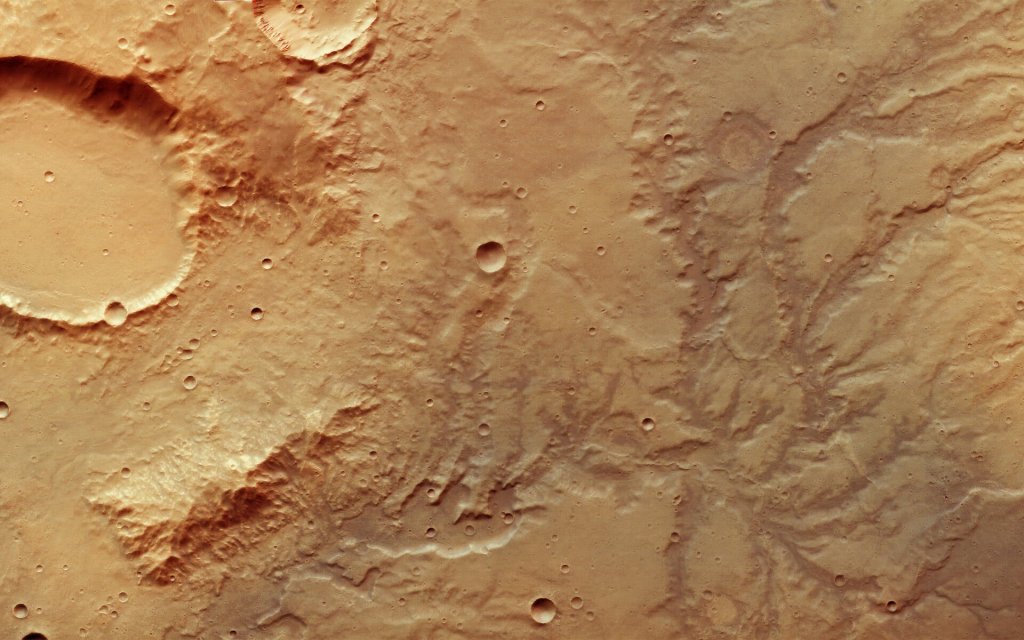

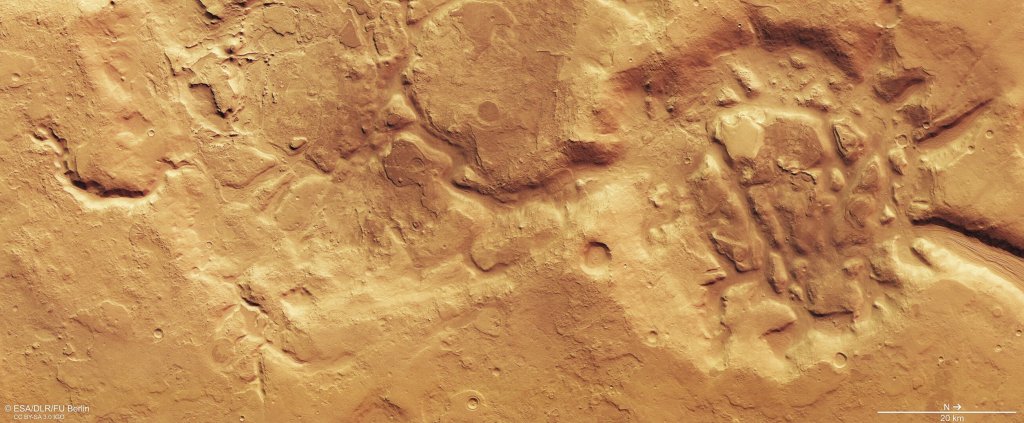

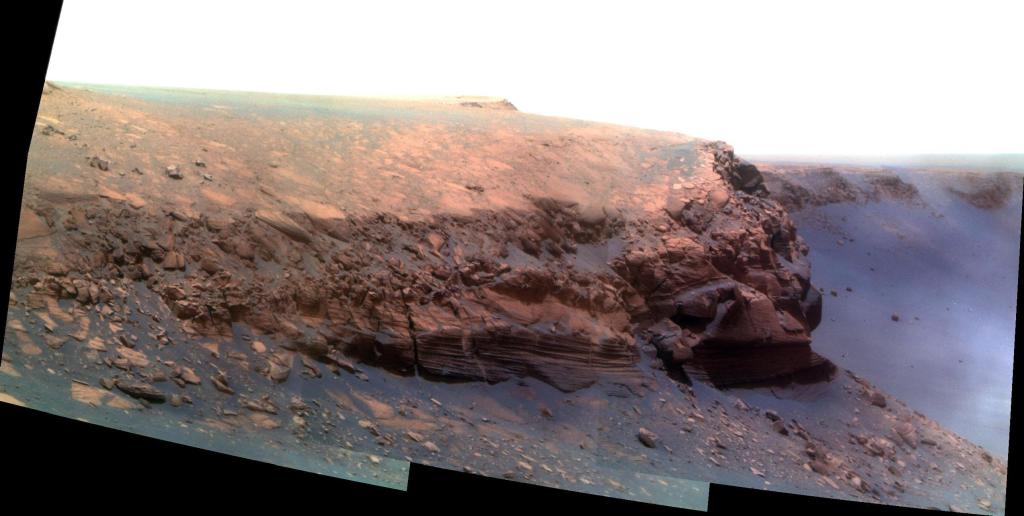

What Scientists Now Know About Mars

Thanks to NASA, ESA, and other science agencies with various countries, we now have a very different picture of Mars. Some parts of Mars have numerous craters like Mercury and the Moon, but other parts of Mars have plains, volcanoes, canyons and river channels. The volcanoes and canyons are bigger than any other known examples. Data prove Mars was warmer and had abundant liquid water in its early history. Today there is still water, but almost all is in the form of ice in the polar caps and below the surface (some locations on Mars may experience temperatures above the melting point of water, hence transient pools of liquid water are possible). There is also the possibility that Mars may have had tectonic plates like the Earth does now. The atmosphere of Mars is mostly carbon dioxide (95%) with nitrogen, argon and traces of oxygen, carbon monoxide, water, methane and other gases, along with dust. The polar caps are partly water ice and partly frozen carbon dioxide, with differences between the northern and southern polar caps.

Apparently, Viking 1 photographs taken in 1976 in the region known as Cydonia look like a human face, but later higher resolution MGS photographs of the same region look like a pile of rocks and it is likely a pareidolia (the tendency to perceive meaning in a natural pattern without significance, like the Man in the Moon).

The Curiosity, Opportunity and Perseverance missions of the Mars Exploration Program have helped determine whether Mars could ever have supported life, and the role of water. The Curiosity rover found that ancient Mars had the right chemistry to support living microbes. Curiosity found sulfur, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon—key ingredients necessary for life—in a sample drilled from the “Sheepbed” mudstone in Yellowknife Bay. Curiosity also found evidence of persistent liquid water on Mars in the past. Organic carbon, found in Mars rocks in samples drilled from Mount Sharp and surrounding plains, are the building blocks of life. The seasonally varying atmosphere of methane suggests links to life and water. Instrumentation also showed that the Martian atmosphere had more water in Mars’ past.

When I was a child—and to this day—I would look up at the deep night, dressed in sparkling stars, often find that red planet blazing in the darkness, and let my mind and heart wander. If given the choice to explore the deep sea or the deep of space, I’d instantly reply: space, of course. I used to wonder why I chose to look up and away, beyond my home, to the far reaches of the unknown blackness of space, and find some thrilling element that provided an abiding fulfillment. Why did I abandon my home? Maybe I didn’t…

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the

Scientists have suggested that we have now slid from the relatively stable Holocene Epoch to the  Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

Take water, for instance. Today, we control water on a massive scale. Reservoirs around the world hold 10,000 cubic kilometres of water; five times the water of all the rivers on Earth. Most of these great reservoirs lie in the northern hemisphere, and the extra weight has slightly changed how the Earth spins on its axis, speeding its rotation and shortening the day by eight millionths of a second in the last forty years. Ponder too, that an age has a beginning and an end. Is climate change the planet’s way of telling us that the

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

In the story, a secret military project sends signals into space to establish contact with aliens. An alien civilization on the brink of destruction captures the signal and plans to invade Earth. One of the main protagonists is Ye Wenjie, a young woman traumatized after witnessing the execution of her scientist father in a brutal cleansing at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Considered a traitor, young Wenjie is sent to a labour brigade in Inner Mongolia, where she witnesses further destruction by humans:

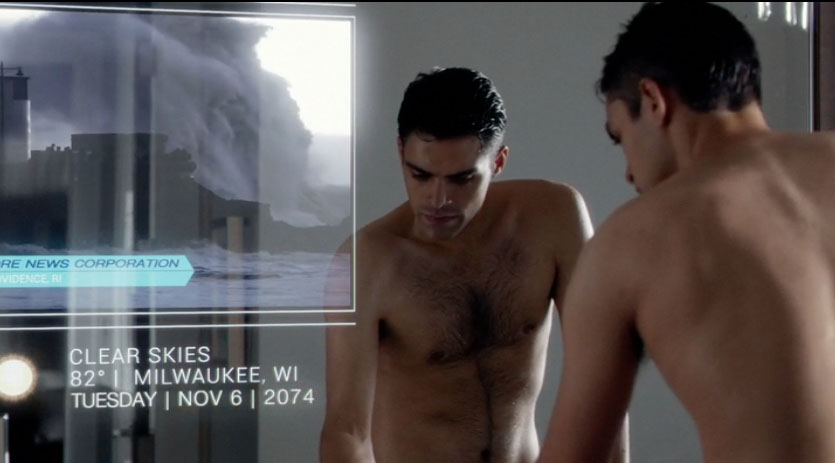

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Incorporated is less thriller than satire; it is less science fiction than cautionary tale.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

Every year the 97% send their 20-year olds to undergo The Process, a grueling Hunger Games-style contest run by the Offshore elite to replenish their numbers. Only 3% of the candidates will be considered worthy. They must pass psychological, emotional and physical tests to earn a place in Mar Alto.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

After the 1967 opening scene with Komarov, we go to the present day with psychologist Jeanne Renoir, conducting an experiment on a child: giving them one marshmallow and leaving the room with the instruction that if they don’t eat the marshmallow but wait for her to return, they’ll get two. Jeanne correctly anticipates the child will eat the marshmallow.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.

The Beyond’s climax, discovery and resolution is really more of a question. The movie doesn’t have a tidy end; its solution is veiled with more questions.