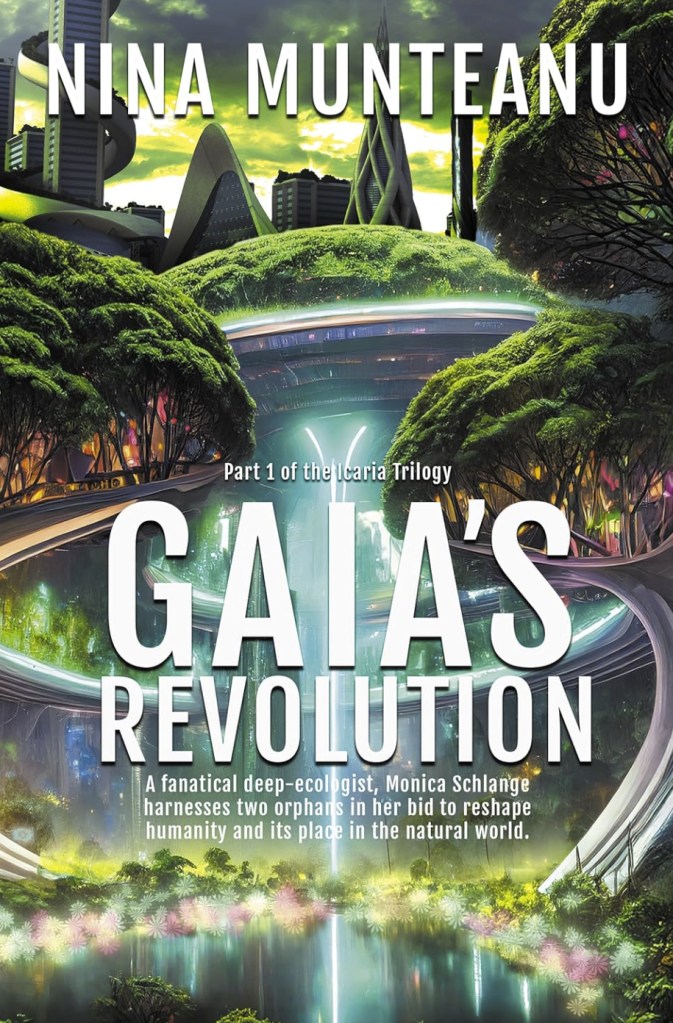

A fanatical deep-ecologist, Monica Schlange, harnesses two orphans in her bid to reshape humanity and its place in the natural world.

.

My upcoming book Gaia’s Revolution (Book 1 of The Icaria Trilogy by Dragon Moon Press) explores a collapsing capitalist society in Canada through ravages of climate change and a failing technology. The story is told through the lives of ambitious twin brothers Eric—a gifted engineer—and Damien Vogel—a brilliant scientist and deep ecologist*—and the woman who plays them like chess pieces in her gambit to ‘rule the world.’

.

The brothers meet at Treffpunkt, a café near Humboldt University in Berlin, nursing Kellerbiers over a late lunch of Einsbein mit Sauerkraut. They argue ideology and reform. Canada represents an ideal canvas for revolution, argues Eric. Damien is puzzled by this. To him Canada represents a quietly reposed nation of polite intellectuals who accept a healthy multicultural society and whose practical leaders are connected with their people. Not a restive rabble ripe for change.

As if reading his brother’s mind, Eric replies:

“Because it’s a huge nation with a lot of space and few people,” Eric argues. “Did you know that Canada holds on average only 4 people per square kilometer? Germany stuffs 240 people in the same area. And China, which is virtually the same size as Canada, holds 153 people per square kilometer.” He picks up Walden Two and waves it at Damien. “Canada is a perfect place to start these [Walden Two colonies called Icarias*]. And, with global warming, we could settle in the boreal.” He then slides the book back in his pocket and leans back, eyes sparkling with purpose. “But the real reason to start a revolution there is because, like you, Canadians are naïve. Even their leaders. And this is because, unlike the rest of the world, they are still asleep…

“Climate is not our enemy, Dame; it’s our friend. Climate is our fierce archangel of change. And let’s not forget that ‘crisis is opportunity…” … He grins, self-pleased, like a wolf in a hen house. Then he practically snarls out, “We must first destroy before we can create. We must be unruly like climate. We must be relentless like climate. We must ride that wave before we can become the wave, Bruder. And then by being that wave, we change the world.”

.

.

The brothers escape the growing racial violence of Berlin, to ‘peaceful’ Canada in a rivalry to control the evolution of the human race. Years later, Eric Vogel, who has created a niche for himself in the technocratic government*, sits in the Canadian prime minister’s office and imagines what a post-capitalist world will look like and how his twin brother Damien—left behind in Germany—would disagree with his vision:

Damien too easily prescribes to the old leftist shibboleth of Nature being the answer to everything and Market being evil. His deep ecology utopia would spring from an atavistic rejection of modern life, a return to ‘the ancient farm.’ But how that fantasy could be achieved without a drastic population reduction is beyond his brother’s imagination. Damien fetishizes the natural world. Just like he does their mother. The naïve fool is a blind romantic, refusing to see reality right in front of him: that Nature is ultimately cruel, cold, and preoccupied with its own survival. Just like their mother.

.

.

Each brother plans to create a new humanity: one to control through gene manipulation and behaviour engineering; the other to empower through biotechnology and transhumanist AI. The warring brothers end up in Canada and set off a violent revolution that destroys the Canadian technocratic government and whose weapons ultimately risk the survival of humanity. Deep ecologist Monica Schlange snares the brothers in her gambit to reshape humanity and its place in the natural world. Three orphaned children, caught in the web of intrigue and violence, will ultimately determine the direction of humanity by introducing the first veemelds (people who can communicate with machines), a new environmental disease (Darwin), and a new set of rules neither brother envisioned.

.

.

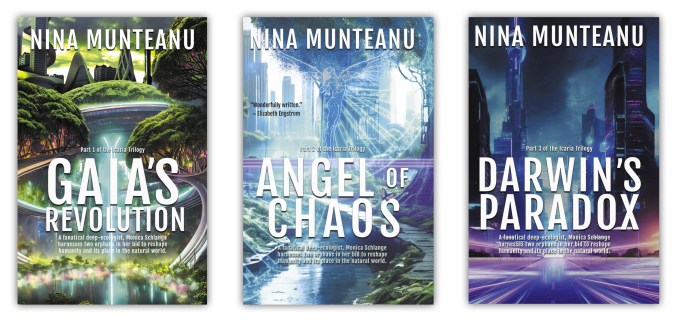

You can pre-order the ebook of Gaia’s Revolution on Amazon. Release date is March 10, 2026. The print version will release soon after. Book 2 (Angel of Chaos) and Book 3 (Darwin’s Paradox) of The Icaria Trilogy are already available in both ebook and print form.

.

.

References:

Munteanu, Nina. 2026. “Gaia’s Revolution, Part 1 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 369 pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2010. “Angel of Chaos, Part 2 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 518 pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2007. “Darwin’s Paradox, Part 3 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 294 pp.

Sessions, George, Bill Devall. 2000. “Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered.” Gibbs Smith. 267pp.

Skinner, B.F. 1948. “Walden Two” The Macmillan Company, New York. 301pp.

.

.

Terminology:

*Deep Ecology: An environmental philosophy and social movement advocating that all living beings have intrinsic value, independent of their utility to human needs. Coined by Arne Naess in 1972, it promotes a holistic, ecocentric worldview—often termed “ecosophy”—that demands radical, structural changes to human society to prioritize nature’s flourishing.

*Icaria: the name of Étienne Cabet’s utopia. Cabet was a French lawyer in Dijon, who published his novel Voyage en Icarie in 1839. The novel was a sort of manifesto-blueprint of utopian socialism, with elements of communism (abolished private property and individual enterprise), influenced by Fourierist and Owenite thinking. Key elements, such as the four-hour work day, are reflected in B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two. The novel explores a society in which capitalist production is replaced by workers’ cooperatives with a focus on small communities.

*Technocracy: A form of government in which the decision-maker(s) are selected based on their expertise in a given area; any portion of a bureaucracy run by technologists. Technocracies control society or industry through an elite of technical experts. The term was initially used to signify the application of the scientific method to solving social problems.

.

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning novelist and short story writer of eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy. She also has three writing guides out: The Fiction Writer; The Journal Writer; and The Ecology of Writing and teaches fiction writing and technical writing at university and online. Check the Publications page on this site for a summary of what she has out there. Nina teaches writing at the University of Toronto and has been coaching fiction and non-fiction authors for over 20 years. You can find Nina’s short podcasts on writing on YouTube. Check out this site for more author advice from how to write a synopsis to finding your muse and the art and science of writing.

.