.

I’ve selected ten TV series that have intrigued me, moved me, and stayed with me for various reasons that touch on: abuse of justice, including eco-justice and environmental abuse; technology use and abuse; and the effects and horrors of climate change.

Some are well known; others not so well known. All approach storytelling with a serious dedication to depth of character, important themes, realistic world building, and excellent portrayal by actors. The world-building is extremely well done—in some cases rivalling Ridley Scott’s best—with convincing portrayals of worlds that are at times uncanny in their realism. Worlds that reflect story from an expansive landscape to the mundane minutiae of daily life: like the cracked phone device of Detective Miller in The Expanse or the dirty fingernails of engineer Juliette Nichols in the Down Deep of Silo. Stories vary in their treatment of important themes from whimsical and often humorous ironies to dark and moody treatises on existential questions. In my opinion, these TV series rival the best movies out there, often reflecting large budgets (but not always) and a huge commitment by producers. The ten TV series I’ve selected in this series come from around the world: Brazil, Germany, France, Norway, Canada and the United States.

In Part 2, I focus on five TV series that explore issues to do with resource allocation, adaptations to climate change and corporate / government biopolitics.

.

.

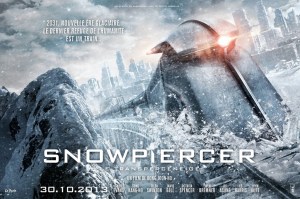

SNOWPIERCER: Capitalism is a Perpetual Motion Train in a Frozen World

.

Snowpiercer is an American post-apocalyptic dystopian thriller that reboots the 2013 film Snowpiercer by Bong Jooh-ho. Snowpiercer is a perpetually moving train that circles the globe carrying the remnants of humanity seven years after the world has become a frozen wasteland, thanks to a botched climate fix. The train is divided up by class – first class, where all the wealthy people live; second and third class where the workers reside, and the tail – the end of the train, where the poor starve, live in total darkness, and are exploited for sex and labor.

.

.

The train, of course, serves as a metaphor for class struggle, elitism and social injustices. The train’s self-contained closed ecosystem is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. The TV show, as with the film, isn’t so much about climate change—as a study on how society functions—or rather copes—within a decadent capitalist system, based on an edict of productivity: serve the machine of “life” and keep the order at all cost. Chief of Hospitality Melanie Cavill (secretly chief engineer of the train) as much as tells this to homicide detective Andre Layton (from the back of the train) when she enlists him to solve the first murder in the elite section of the train.

.

.

The TV show diverges from the film in several important ways.

My original review of the movie touched on style and political agenda:

Bong Joon-Ho’s 2013 motion picture Snowpiercer is a stylish post-climate change apocalypse allegory. A dark pastiche of surrealistic insanity, welded together with moments of poetic pondering and steam-punk slick in a frenzied frisson you can almost smell. Joon-Ho casts each scene in metallic grays and blues that make the living already look half-dead. The entire film plays like a twisted steampunkish baroque symphony. Violence personified in a garish ballet.

.

.

I drew on Aaron Bady’s commentary on the film in The New Inquiry which discussed reform capitalism* to conclude that the movie “Snowpiercer is about hard choices and transcendence. Save humanity but at the consequence of our souls? Or transcend the machine that has robbed us of our souls at the expense of our mortality? The film continually questions our definition of what life is and what makes life worth living … Ultimately, Bong Jung-Ho’s message with the ending of this baroque political allegory is the vindication of a choice against reform capitalism for something new, that there is indeed “Life after Capitalism”, not easy but worth living…”

The Snowpiercer TV series takes a different approach to the end of the world and capitalism metaphor, weaving in more intrigue in its plot (a murder) with elements of detecting by the only homicide detective left on the train and in the world—a self-styled revolutionary from the back of the train. Much of the entertaining tensions arise from the interactions of Detective Andre Layton (Daveed Diggs) and Hospitality head Melanie Cavill (Jennifer Connelly) and second in command Ruth Wardell (Alison Wright); there are also strong performances by the train’s Breakman, Bess Till (Mickey Sumner) and later Mr. Wilford (Sean Bean) who was supposedly running the train but had been secretly thrown off the train by head engineer Cavill.

.

.

The focus of the TV show has been more on the potential survival of a handful of what’s left of humanity with competing agendas on how this is best achieved, whether the freeze is indeed unfreezing and some part of the world has become hospitable or at least livable. Trading the film’s baroque metaphors to capitalism for a more literal approach to climate change and living in a post climate change world, the TV series focuses more on real questions facing this ragtag of humanity. How to keep it together when rifts naturally form based on unequal resource allocation and space in the limited ecosystem of the train. Given that the show plays out in several seasons, there is room to expand and further explore socialism, democracy, fascist rule and environmental activism. Class divisions are explored through a large cast of morally ambiguous characters, each with a plot arc, and more opportunities to explore not just first class but second and third class, showcasing more nuanced and varied elements to the class struggle and ambitions of people.

.

.

*Reform Capitalism: “Reform and revolution are shibboleths that distinguish liberals from radicals,” explains Aaron Bady of The New Inquiry. “While liberals want to reform capitalism, without fundamentally transforming it, radicals want to tear it up from the roots (the root word of “radical” is root!) and replace capitalism with something that isn’t capitalism…If you’re the kind of leftist who thinks that the means of production just need to be in better hands—Obama, for example, instead of George W. Bush, or Elizabeth Warren instead of Obama, or Bernie Sanders instead of Elizabeth Warren, and so on—then this movie buries a poison pill inside its protein bar: soylent green is people.”

.

Ten Significant Science Fiction TV Series:

Biohackers (Germany)

Orphan Black (Canada)

Occupied (Norway)

Missions (France)

Expanse (USA)

Incorporated (USA)

3% (Brazil)

Snowpiercer (USA)

Silo (USA)

Extrapolations (USA)

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction. I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it.

I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it. Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility).

Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility). The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Settings can not only have character; they can be a character in their own right. A novelist, when portraying several characters, may often find herself painting a portrait of “place”. This is setting being “character”. The setting functions as a catalyst, and molds the more traditional characters that animate a story. The central character is often really the place, which is often linked to the protagonist. In Lord of the Rings, for instance, Frodo is very much an extension of his beloved Shire.

Settings can not only have character; they can be a character in their own right. A novelist, when portraying several characters, may often find herself painting a portrait of “place”. This is setting being “character”. The setting functions as a catalyst, and molds the more traditional characters that animate a story. The central character is often really the place, which is often linked to the protagonist. In Lord of the Rings, for instance, Frodo is very much an extension of his beloved Shire.

Use similes, metaphors, and personification to breathe life into setting

Use similes, metaphors, and personification to breathe life into setting