In her masters thesis published in November 2025 at the University of Graz, Austria, Şeyma Yonar uses my short story The Way of Water, along with several others to explore and discuss the importance of eco-literature in establishing ecological awareness and ultimately ecological and sustainable action.

.

.

.

Yonar draws on the work of Maria Löschnigg to argue that “as the environmental crisis encompasses not just physical challenges but also a crisis of imagination, posing questions about life in severely degraded environments, it becomes crucial to examine how literature can inspire interest in ecological issues and foster a deeper environmental awareness.” Yonar further draws on the works of Serpil Oppermann and Susan O’Brian to note that ecocriticism tends to neglect less conventional but equally meaningful speculative or experimental fiction in its critical gaze of relevant eco-literature and to question whether realism should be the dominant mode for ecological discourse.

.

.

“The Way of Water is a strong eco-story that possesses many layers and elements that strengthen its narrative while encouraging readers to engage with its world…The notion what water constitutes the essence of life is the central theme of the story … Munteanu’s knowledge as a scientist enables her to create a convincing scientist protagonist whom she embeds into a powerful fictional story. Water, particularly in this eco-story acts not only as a symbolic entity but also as a body of force…the agency of water is presented as a dynamic, living entity, central to the narrative’s ecological themes.”

“Munteanu’s impactful storytelling highlights her significant contribution to Canadian literature, particularly through her engagement with pressing environmental issues and her commitment to fostering ecological awareness through fiction.”

.

.

Yonar draws on the work of Serpil Oppermann, who points out in her book Blue Humanities, that water is deeply connected to social and cultural realities, and stories that highlight its narrative role are both essential and impactful. “Non-human-centred narratives reveal the dynamic and active nature of water, making its agency understandable and natural to the reader.”

Yonar quotes beginning lines of the short story to demonstrate how a powerful metaphor can become surprisingly literal: In this passage the main character Hilda thinks: water is a shape-shifter. It changes yet stays the same, shifting its face with the climate. It wanders the earth like a gypsy, stealing from where it is needed and giving whimsically where it isn’t wanted: “A statement,” Yonar writes, “that initially appears to be metaphorical rather than literal description of water. However, as the story expands, it becomes evident that this ‘shape-shifting’ feature is not an unrealistic trait, but rather a reflection of water’s dynamic and transformative nature.” She adds that, “this characterization of water points out its agency, suggesting its ability to adapt and influence the narrative in ways that transcend traditional understandings.”

.

.

Yonar notes that intertextuality used in The Way of Water—such as wCard, iTap and Schrödinger’s Water is a useful way to “foreground notions of relationality, interconnectedness and interdependence in modern cultural life” (Graham Allen). Intertextuality in The Way of Water reflects capitalist industrialism: the monetization, commodification and control of water by national utilities represented by CanadaCorp: the “corporate dominance, digital dependence, and pervasive nature of technology.” Yonar adds pithily, “In a manner analogous to how Apple products have become indispensable instruments in contemporary existence, the iTap within Munteanu’s narrative operates as an emblem of hyper-connectivity and authority, thereby amplifying the novel’s critique of technological dependency in modern society.” Yonar ponders that the thought experiment of Schrödinger’s Cat, reimagined through the element of water as Schrödinger’s Water, “reframes the original paradox within an ecological and environmental context, emphasizing the fluidity and uncertainty of water’s role in shaping human and non-human existence.”

Yonar shares with Meyer and Oppermann “a unified perspective on the collaborative role of writers and scientists in addressing the shared challenge of climate change.” Yonar concludes that The Way of Water introduces a powerful human-made cooperation that is at the same time political, suppresses people, and takes advantage of the scarcity of water. Even “the rain belonged to CanadaCorp,” she quotes from The Way of Water.

.

.

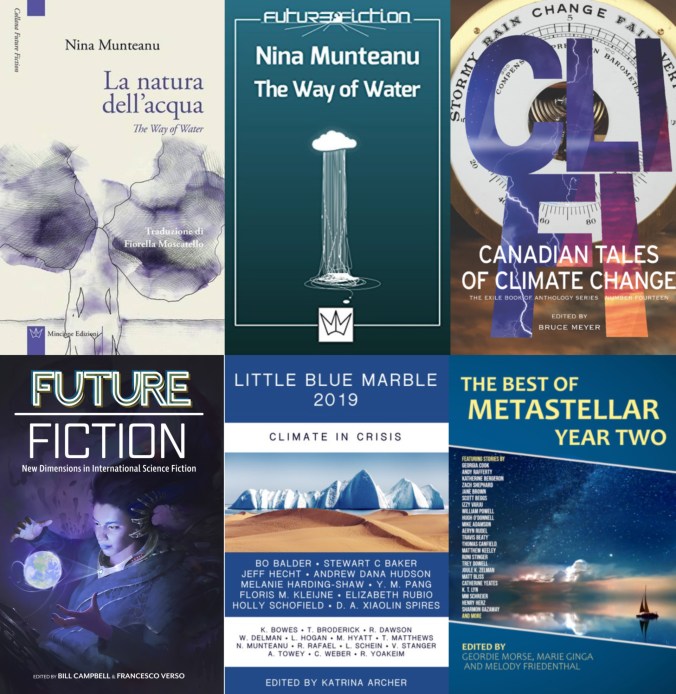

The Way of Water was first published as a bilingual print book by Mincione Edizioni (Rome) in Italian (La natura dell’acqua, translated by Fiorella Moscatello), and English along with a recounting of what inspired it: The Story of Water (La storia dell’acqua) in 2016. To date, The Way of Water has been published and republished eight times throughout the world and translated into Italian and German. I think this success is less a reflection of my writing than the immediacy and importance of the topic covered: growing water scarcity, its commodification, and its politicization.

.

I’ve written several articles on how The Way of Water came about. Briefly, it all started with an invitation in 2015 by my publisher in Rome to write about water and politics in Canada. I had long been thinking of potential ironies in Canada’s water-rich heritage. The premise I wanted to explore was the irony of people in a water-rich nation experiencing water scarcity: living under a government-imposed daily water quota of 5 litres as water bottling and utility companies took it all.

Latest publication of The Way of Water in Nova 37, translated into German as Der Weg des Wassers

.

.

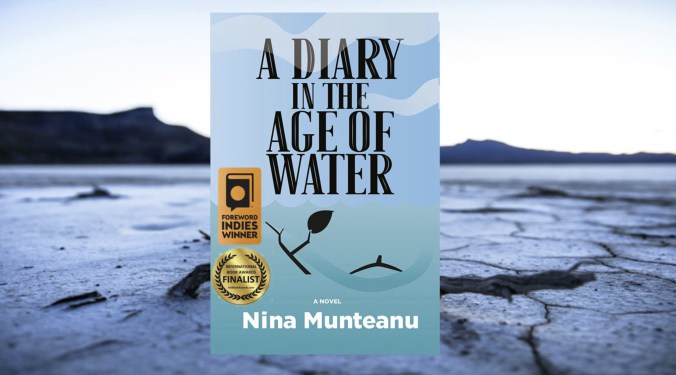

The Way of Water, in turn, inspired my dystopian novel A Diary in the Age of Water (Inanna Publications, 2020), which chronicles the lives of four generations of women and their relationship to water during a time of severe water restriction and calamitous climate change. The novel features the main character Hilda from The Way of Water and her limnologist mother; A Diary in the Age of Water is essentially the mother’s diary embedded in a larger story. Through a series of entries, the diarist reflects on the subtle though catastrophic occurrences that will eventually lead to humanity’s demise.

.

.

References:

Löschnigg, Maria. 2014. “The Contemporary Canadian Short Story in English: Continuity and Change.” Cultures in America in Transition, vol. 7, WVT.

Munteanu, Nina. “The Way of Water” Mincione Edizioni, Rome. 113pp.

Munteanu, Nina. “A Diary in the Age of Water.” Inanna Publications, Toronto, ON. 328pp.

Meyer, Bruce. 2017. “Introduction to “Cli Fi: Canadian Tales of Climate Change“

Fi: Anthology #14. Edited by Bruce Meyer. Exile Editions, Toronto.304pp.

O’Brian, Susan. 2001. “Articulating a World of Difference: Ecocriticism, Post colonialism and Globalization.” Canadian Literature vol. 170-171: 140-158.

Oppermann, Serpil. 2023. “Blue Humanities.” Cambridge University Press.

Yonar, Şeyma. 2025. “Short Texts—Long Term Effects: The Canadian Eco-Story.” Masters Thesis, University of Graz, Austria. 70pp.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning novelist and short story writer of eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy. She also has three writing guides out: The Fiction Writer; The Journal Writer; and The Ecology of Writing and teaches fiction writing and technical writing at university and online. Check the Publications page on this site for a summary of what she has out there. Nina teaches writing at the University of Toronto and has been coaching fiction and non-fiction authors for over 20 years. You can find Nina’s short podcasts on writing on YouTube. Check out this site for more author advice from how to write a synopsis to finding your muse and the art and science of writing. For more on her work as a limnologist and ecologist, see The Meaning of Water.

.

My short story “Out of the Silence,” which appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of

My short story “Out of the Silence,” which appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of

In her 1997 biography Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, historian and science biographer Linda Lear wrote:

In her 1997 biography Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, historian and science biographer Linda Lear wrote:

“Miss Rachel Carson’s reference to the selfishness of insecticide manufacturers probably reflects her Communist sympathies, like a lot of our writers these days. We can live without birds and animals, but, as the current market slump shows, we cannot live without business. As for insects, isn’t it just like a woman to be scared to death of a few little bugs! As long as we have the H-bomb everything will be O.K.”

“Miss Rachel Carson’s reference to the selfishness of insecticide manufacturers probably reflects her Communist sympathies, like a lot of our writers these days. We can live without birds and animals, but, as the current market slump shows, we cannot live without business. As for insects, isn’t it just like a woman to be scared to death of a few little bugs! As long as we have the H-bomb everything will be O.K.”