Montreux, Switzerland (photo by Nina Munteanu)

In Part 1, Gnosis, I explored the nature of our current worldview, its shifting face and how literature and women writers have both contributed and enlightened this shift.

I talked with four women, all in the science fiction or eco-fiction genres; two are writers, and two are publishers. We discussed this shift, what it looks like, what the “feminine archetype” means and the nature of “Optimistic SF.”

When asked to describe SF today, Lynda Williams, author of the Okal Rel series, argued that, “SF is mainstream now … It has grown up, emotionally, from being about wish-fulfilling technologies … to embracing the social implications of change.” Stephanie Johanson, editor and co-publisher of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, notes that, “Science fiction often reflects the views of the day, following and expanding on newer technologies.” Williams adds that SF fiction has gained a literary presence, but at some expense: “now there’s a sordid fascination, in a lot of self-consciously dark SF, with self-interested cynicism and extended analogies to drug addiction as a means of coping with reality.” Johanson provided a different perspective. “Stories that predict doom have been around since the beginning of SF,” she argued. “But lately perhaps there might be more stories with a glimmer of hope … perhaps it won’t be science that destroys us … the right sciences might actually save us.” Editor and Publisher of On Spec Magazine, Diane Walton shares that she is seeing a lot of Post-Apocalyptic submissions, “mainly because it’s interesting to put your characters in a setting where the rules don’t apply any more. They have to try to rebuild the life and security and order they used to have, or else revert to savagery, or else adapt to a whole new set of circumstances—the choices are endless. Except zombies. I don’t want to see any more zombies.”

When asked if SF had a role in literature, Johanson suggested that, “SF has fewer limitations and more frontiers to explore than other genres.” Both Johanson and Walton suggest that its main role is to challenge our preconceived notions of the world and “open up the mind to new possibilities.” Walton and Williams agree that SF is recognized more today as “real” literature rather than being dismissed as “escapism.” Williams shares that SF’s roots are as old as myth. “Like myths and bible stories, SF is an instructive literature, pointing out how things can go wrong (or right) and why. The growing up SF has done since the 1950s lies in an increasing recognition that [humanity is its] own worst enemy and a better understanding of human nature is crucial to the problems we face, not just the hard sciences.”

I shared that I had witnessed (at least in my classrooms and writing workshops) a rising ecological awareness, reflected in a higher percentage of new writers bringing in works-in-progress (WIPs) that were decidedly “eco-fiction” or “climate fiction.”

“I have always gravitated towards, and often found, literature with ecological components,” Sarah Kades, author of Claiming Love confides. She then adds, “But I do agree with you that ecological awareness is not only gaining momentum, it is front and centre for many, and as such, we are naturally finding it more and more in literature.”

“I never thought of my own work as ecological,” shares Williams. “But it’s true: the underlying issue in it is how does, or can, the collective will prevent groups or individuals from destroying what is irreplaceably precious…Yes, I think SF has graduated from a fascination with building bigger death rays to tackling questions of how we avoid committing the unthinkable while still indulging in lots of entertaining conflict. Because conflict must exist in any story. We wouldn’t be human without it. There’s plenty of conflict in an ecosystem, too, but it stays balanced. SF used to be optimistic about scientific discoveries shifting the system out of balance in the direction of net gain for humankind. And this has happened. Even today’s poor are richer than yesterday’s. What worries us, increasingly, is whether some sudden imbalance could tip us into irreversible catastrophe because unlike 1950s readers we don’t trust smart and powerful people to act sanely in their quest for power.”

“I think that authors have come to a realization that the setting of a book can be just as strong a character (and character-builder) as the people in it,” says Walton. “Humans are so vulnerable, and must depend on their brains and skills at manipulating the environment to be able to adapt to harsh and potentially life-threatening situations…We don’t have fur, for example, or the ability to burrow under the sand to find shelter from a hot sun. So the books that embrace the environment, and that use it to present character-building challenges to the protagonists, can be more interesting than just a ‘good guys against bad guys’ story in any genre.”

Johanson provokes with the concept of awareness-guided perception—itself a valid cultural metric: “Perhaps there is an increase of ecological awareness in literature, or perhaps we are just noticing stories that have always been there.” This notion was discussed in a recent panel on Eco-Fiction in which I participated with Susan Forrest, Michael J. Martineck, Hayden Trenholm, and Sarah Kades at the writer’s festival When Words Collide in Calgary. One author pointed out that environmental fiction has been written for years and it is only now—partly with the genesis of the term eco-fiction—that the “character” and significance of environment is being acknowledged beyond its metaphor; for its actual value. It may also be that the metaphoric symbols of environment in certain classics are being “retooled” through our current awareness much in the same way that Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World or George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four are being re-interpreted—and newly appreciated— in today’s world of pervasive surveillance and bio-engineering. Johanson cites Brian Aldiss’ Helliconia trilogy, John Varley’s Titan trilogy, Joan D. Vinge’s The Snow Queen, and the works of Jules Verne. Classic titles Walton remembers from her younger days include John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar and Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Word for World is Forest; and more recently, The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi. Walton includes the 1965 Dune series by Frank Herbert, given that the environment of the desert and how humanity has adapted to it plays a major role in the series.

I proposed that an awakening to the feminine archetype (cooperation, compassion, relationship, altruism) is occurring and currently reflected in literature. Johanson suggested that, “If [cooperation, compassion, relationship, and altruism] are used in balance with science and logic, there can be an optimistic future.” Had she seen this increasing in literature? “I don’t think so, but perhaps I have been reading the wrong stories,” Johanson admits. Kades shares a different perception. “I would definitely agree there is an awakening to the feminine archetype in our culture as a whole, and literature is reflecting this,” she argues. “The books that resonate most strongly for me are the ones that honour and celebrate both the feminine and masculine, stories that demonstrate mutual respect and successful collaboration between men and women. Throw humour and romance in there, too, and it’s irresistible.”

Walton observes that, “It’s definitely something that drives a story in a different direction from the more “male” pursuits of taking everything by force, or the lone-wolf hero solving problems without any collaboration with others.” She confides, “I loved the new Mad Max film, where compassion and collaboration made the story come alive. And yet, it has been accused, by some, of being a feminist propaganda film.”

Williams answers with a tale of two characters. “Amel, my prince-raised-as-pauper, is a hero of the pol virtues. Loosely speaking, we could call the pol virtues feminine. Horth Nersal, on the other hand, is an alpha male—a hero of the rel variety in Okal Rel theology. There are important female characters in my saga, but I have to confess my teenage self was simply more fascinated with heroic males for reasons inaccessible to my older, sager self. So, in my own work I could make the case that Amel’s problem-solving and character development is absolutely an example of an awakening to the feminine archetype. And he does wind up in power. But even as Amel gets his act together, after book six, and learns to use his more subtle kind of influence to make the world behave, Horth Nersal starts stealing the spotlight. I don’t quite know how this happened. And maybe Amel’s central, anchoring role throughout the series argues in favor of the feminine principle dominating. But I think the Amel/Horth dilemma isn’t unique to my own work. I see it crop up in other SF where, on the face of things, one might say the feminine archetype is in ascendance.”

Can we (as writers and editors and otherwise) foster such a change in worldview and gain a sense of place, purpose and meaning in our lives through it?

“If writers are writing stories to change the world, and I hope some are, then they should write stories that first entertain,” Johanson advises writers. “It doesn’t matter how great a theory, or how good an idea, if it doesn’t entertain, fewer people will read it. This also applies to editors. Karl and I decided early on that we wanted to teach people with the stories we published in Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine. We wanted our readers so entertained that they wouldn’t necessarily realize that their views had just been broadened.”

“As a writer I feel a rather persuasive responsibility to help foster positive social change,” says Kades. “For me it is considerable motivation of the stories that take turns between calming, weaving, and banging around in my head, eager to get out. And stories don’t have to tackle epic social issues to be a conduit of positive social change. Stories that create new ‘normals’ of compassion, respect and tolerance are just as important and interesting as stories that address specific social issues. To create change, first we must imagine it. Writers can help with that.”

“I’ve been reading and thinking a lot about meaning and purpose these days,” Williams confides. “First, we need to foster creativity in others and respect it in ourselves. But in both cases we must challenge our creative cravings to do work. I personally believe the richest entertainment comes not just from simple wish-fulfillment narratives – although these are fun and perfectly at home in epic literature – but from touching a raw nerve here and there, and making sure the ‘bad guys’ are at least as realistic as the heroes, not just straw men defeated by a better ray guy. Best of all, can a resolution be found in which the bad guys co-exist with their conquerors? At least think about it, and how your society might avoid problems cropping up again, and make that part of the fabric of your tale.”

“I’m not sure I agree with this being part of my role as an editor,” Walton shared. “It may be that I am drawn more to the kinds of books and stories that espouse this concept, and thus more likely to buy them to publish. We are all gatekeepers of some kind or another. One thing that is interesting is the recent brouhaha over the Hugo awards, where, I think, the various ‘puppy’ slates would look on any sort of eco-fiction that embraced the feminine archetype as being something only a Social Justice Warrior would like. Some people just don’t want their worldview changed, I guess.”

…Which brings me to “Optimistic SF” and what it represents. In a recent discussion with Lynda Williams over several Schofferhofers at Sharkey’s Pub in Vancouver, we shared our thoughts on how the evolution of the science fiction genre and the place that optimism holds in literature and art, generally. Is “saving the world” and “The Hero’s Journey” still viable in literature today? And how many Schofferhofers does it take to get there?

“I’ve asked people to help me define ‘Optimistic SF’ on my blog,” Lynda shares. “Check out what we’ve got so far at http://realityskimming.com/2015/09/10/fall2015optimisticsf/ and leave your own suggestions if something springs to mind. My own definition has to do with how a story makes me feel. If I’m entertained and emerge feeling there’s some point to living another day rather than convinced human beings are a bad idea best eliminated quickly before they do more harm, it’s optimistic SF. I want to encourage the notion that it’s not dumb or simple minded to strive for improving the world or defending moral behavior when feasible.”

Johanson adds that, “I became a fan of SF, because of stories that I might now classify as ‘Optimistic SF’, stories that made me look forward to the future, characters that I would love to have as friends, and places I wanted to explore. Optimistic literature to me isn’t free from problems. It wouldn’t be a story if everything was splendid. It is conflict that makes a story, but optimistic SF solves problems, and by the end of the story things are looking that much brighter. Anne McCaffrey wrote a lot of ‘Optimistic SF’. I was very fond of her Dragons of Pern series, though the later books by her son Todd McCaffrey seem far less optimistic in nature. I found many of Larry Niven’s novels to be optimistic, like the Ringworld books. Lynda Williams’ Okal Rel novels have a lot of suffering in them, but her series has always seemed like ‘Optimistic SF’.” For Johanson, optimistic SF has at least one optimistic character, one positive goal achieved and a positive [resolved as opposed to ‘happy’] ending, not “leaving evil posed to strike.” She suggests that this includes “overcoming adversity, exploring, discovering, and/or self-growth.”

Walton submits that optimistic SF is, in fact, a challenge to write, “because you still need to have some kind of antagonist (be it human, alien or environment) to make the protagonist want or need something enough to take risks and go on that literary journey. Maybe the optimism comes from stories that are ‘less dark’ than others?”

Lynda Williams openly shared her ambitions for her recent publishing venture, Reality Skimming Press: “Reality Skimming Press is my answer to how to continue being creative now I’m post-published. Not just to keep the Okal Rel Saga in print, although that’s my core motivation for even considering becoming a publisher. But to be brazen enough to talk about ideas and art and what it means to be optimistic, for example, instead of bowing to the demands of commercial success and elusive, fickle fame. Arguably, Reality Skimming Press is the ultimate feminine solution where the meaningfulness of the work and quality of the relationships, on and off the page, trump the call to do battle for the big prizes. Success is lovely, of course. And showers of gold and fame wouldn’t be scornfully rejected. It’s more a case of asking the question: ‘Would I do this even if I never got rich or famous?’ And if the answer is ‘yes’ to have the courage to keep enjoying the journey.”

Sarah Kades echoed my initial discovery in “responsibility and connection,” noted in my first article, with her admission: “It was rather startling [to] first realize [that] the responsibility I feel [in writing] socially relevant stories is not universally held among writers. It is not, which is of course just fine; it just surprised me because of how [strong] it is in me. The knowledge brought my writing and my voice into sharper focus for me.”

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning Canadian ecologist and novelist. In addition to eight published novels, she has authored short stories, articles and non-fiction books, which have been translated into several languages throughout the world. She is currently an editor of European zine Europa SF and writes for Amazing Stories. Nina teaches writing at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Her latest book “Water Is…” (release May 10 2016 by Pixl Press; available for pre-order April 12) is a non-fiction examination of the meaning of water.

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning Canadian ecologist and novelist. In addition to eight published novels, she has authored short stories, articles and non-fiction books, which have been translated into several languages throughout the world. She is currently an editor of European zine Europa SF and writes for Amazing Stories. Nina teaches writing at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Her latest book “Water Is…” (release May 10 2016 by Pixl Press; available for pre-order April 12) is a non-fiction examination of the meaning of water.

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and editor of the growing collection of works by Hal Friesen, Craig Bowlsby, Krysia Anderson, Elizabeth Woods, Nina Munteanu, Randy McCharles and others writing works set in the ORU. As a publisher, she is working with Kyle Davidson, Jeff Doten, Sarah Trick, Jennifer Lott, Paula Johanson, Lynn Perkins and Yukari Yamamoto in re-inventing publishing through Reality Skimming Press. Lynda holds three degrees and works as Learning Technology Analyst and manager of the Learn Tech support team at Simon Fraser University. She teaches part-time at BCIT.

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and editor of the growing collection of works by Hal Friesen, Craig Bowlsby, Krysia Anderson, Elizabeth Woods, Nina Munteanu, Randy McCharles and others writing works set in the ORU. As a publisher, she is working with Kyle Davidson, Jeff Doten, Sarah Trick, Jennifer Lott, Paula Johanson, Lynn Perkins and Yukari Yamamoto in re-inventing publishing through Reality Skimming Press. Lynda holds three degrees and works as Learning Technology Analyst and manager of the Learn Tech support team at Simon Fraser University. She teaches part-time at BCIT.

Sarah Kades hung up her archaeology trowel and bid adieu to Traditional Knowledge facilitation to share her love of the natural world and happily-ever-afters. She writes literary romantic eco-fiction where nature, humour and love meet. She lives in Calgary, Canada with her family. Connect with Sarah on Facebook, Twitter and www.sarahkades.com.

Sarah Kades hung up her archaeology trowel and bid adieu to Traditional Knowledge facilitation to share her love of the natural world and happily-ever-afters. She writes literary romantic eco-fiction where nature, humour and love meet. She lives in Calgary, Canada with her family. Connect with Sarah on Facebook, Twitter and www.sarahkades.com.

Stephanie Johanson is the art director, assistant editor, and co-owner of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, publishing since 2003. She is an artist who has worked in a variety of media, though painting and soapstone carving are her passions. Stephanie paints realism with a hint of fantasy, often preferring landscapes as her subjects. Examples of her work can be viewed on the Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine website at www.neo-opsis.ca/art.

Stephanie Johanson is the art director, assistant editor, and co-owner of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, publishing since 2003. She is an artist who has worked in a variety of media, though painting and soapstone carving are her passions. Stephanie paints realism with a hint of fantasy, often preferring landscapes as her subjects. Examples of her work can be viewed on the Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine website at www.neo-opsis.ca/art.

.

Diane Walton is currently serving a life sentence as Managing Editor of On Spec Magazine, and loving every minute of it. She and her lovely and talented husband, Rick LeBlanc, share their rural Alberta home with three very entitled cats.

Diane Walton is currently serving a life sentence as Managing Editor of On Spec Magazine, and loving every minute of it. She and her lovely and talented husband, Rick LeBlanc, share their rural Alberta home with three very entitled cats.

After she and fellow colonists crash land on the hostile jungle planet of Mega, rebel-scientist Izumi, widower and hermit, boldly sets out against orders on a hunch that may ultimately save her fellow survivors—but may also risk all. As the other colonists take stock, Izumi—obsessed with discovery and the need to save lives—plunges into the dangerous forest, which harbors answers, not only to their freshwater problem, but ultimately to the nature of the universe itself. Mega was a goldilocks planet—it had saltwater and supported life—but the planet also possessed magnetic-electro-gravitational anomalies and a gravitational field that didn’t match its size and mass. The synchronous dance of its global electromagnetic field suggested self-organization to Izumi, who slowly pieced together Mega’s secrets: from its “honeycomb” pools to the six-legged uber-predators and jungle infrasounds—somehow all connected to the water. Still haunted by the meaningless death of her family back on Mars, Izumi’s intrepid search for life becomes a metaphoric and existential journey of the heart that explores how we connect and communicate—with one another and the universe—a journey intimately connected with water.

After she and fellow colonists crash land on the hostile jungle planet of Mega, rebel-scientist Izumi, widower and hermit, boldly sets out against orders on a hunch that may ultimately save her fellow survivors—but may also risk all. As the other colonists take stock, Izumi—obsessed with discovery and the need to save lives—plunges into the dangerous forest, which harbors answers, not only to their freshwater problem, but ultimately to the nature of the universe itself. Mega was a goldilocks planet—it had saltwater and supported life—but the planet also possessed magnetic-electro-gravitational anomalies and a gravitational field that didn’t match its size and mass. The synchronous dance of its global electromagnetic field suggested self-organization to Izumi, who slowly pieced together Mega’s secrets: from its “honeycomb” pools to the six-legged uber-predators and jungle infrasounds—somehow all connected to the water. Still haunted by the meaningless death of her family back on Mars, Izumi’s intrepid search for life becomes a metaphoric and existential journey of the heart that explores how we connect and communicate—with one another and the universe—a journey intimately connected with water. Fingal’s Cave

Fingal’s Cave Fingal’s Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The cave is formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns in a Paleocene lava flow (similar to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland). Its entrance is a large archway filled by the sea. The eerie sounds made by the echoes of waves in the cave, give it the atmosphere of a natural cathedral. Known for its natural acoustics, the cave is named after the hero of an epic poem by 18th century Scots poet-historian James Macpherson. Fingal means “white stranger”.

Fingal’s Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The cave is formed entirely from hexagonally jointed basalt columns in a Paleocene lava flow (similar to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland). Its entrance is a large archway filled by the sea. The eerie sounds made by the echoes of waves in the cave, give it the atmosphere of a natural cathedral. Known for its natural acoustics, the cave is named after the hero of an epic poem by 18th century Scots poet-historian James Macpherson. Fingal means “white stranger”.

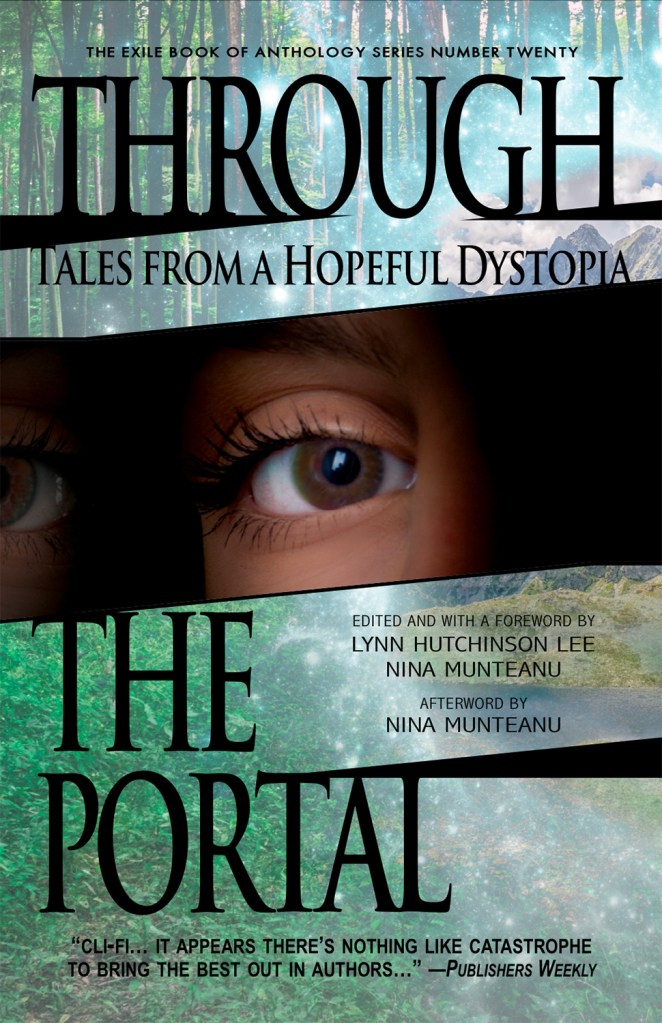

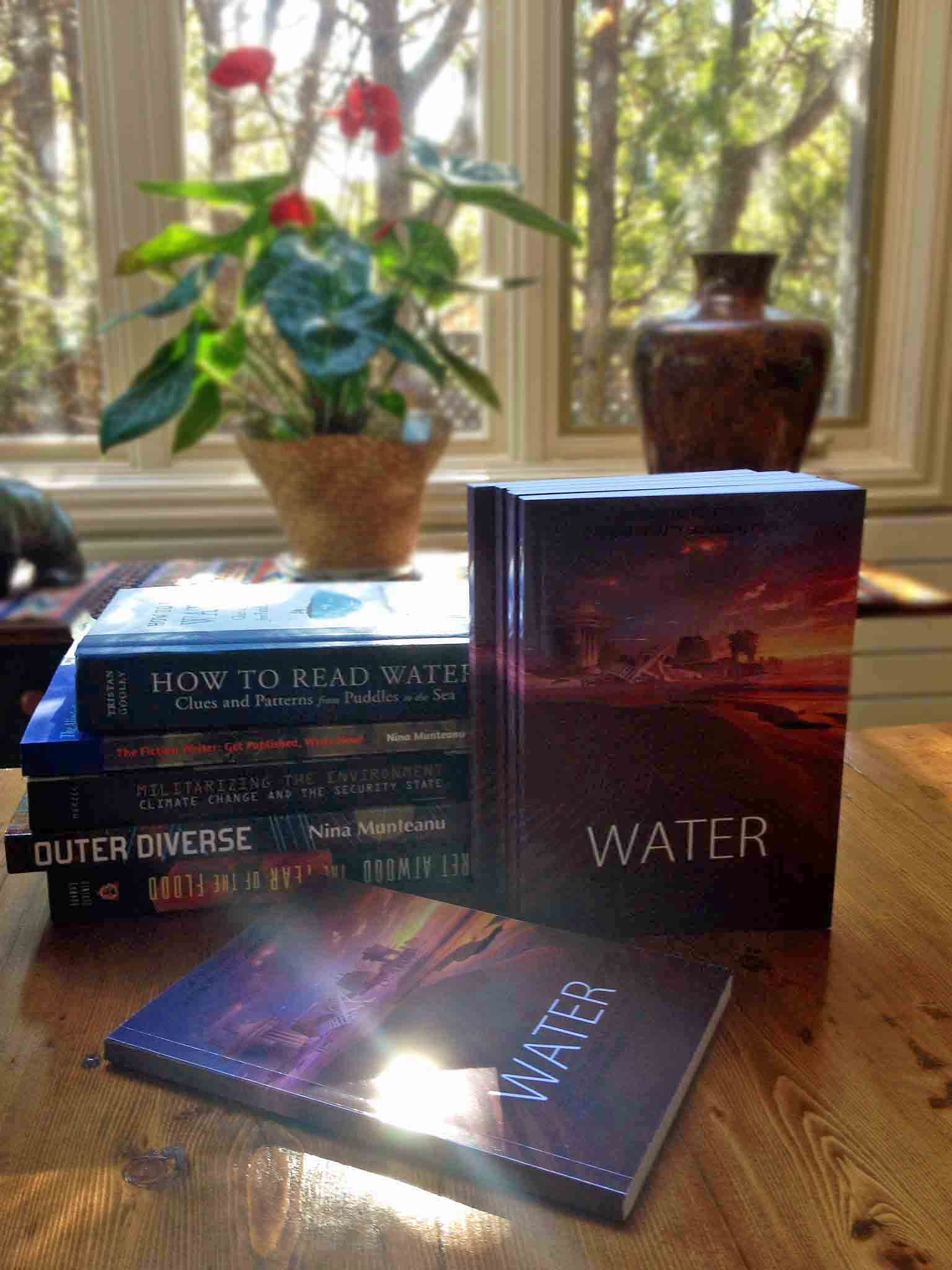

In December 2017, “Water”, the first of Reality Skimming Press’s Optimistic Sci-Fi Series was released in Vancouver, BC. I was invited to be one of the editors for the anthology, given my passion for and experience with water.

In December 2017, “Water”, the first of Reality Skimming Press’s Optimistic Sci-Fi Series was released in Vancouver, BC. I was invited to be one of the editors for the anthology, given my passion for and experience with water.

In the years that followed, Reality Skimming Press published several works, including the “Megan Survival” Anthology for which I wrote a short story, “

In the years that followed, Reality Skimming Press published several works, including the “Megan Survival” Anthology for which I wrote a short story, “

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Whether told through cautionary tale / political dystopia (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy; Bong Jung-Ho’s Snowpiercer), or a retooled version of “alien invasion” (e.g., Cixin Liu’s 2015 Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem), these stories all reflect a shift in focus from a technological-centred & human-centred story to a more eco- or world-centred story that explores wider and deeper existential questions. So, yes, science fiction today may appear less technologically imaginative; but it is certainly more sociologically astute, courageous and sophisticated.

Whether told through cautionary tale / political dystopia (e.g., Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy; Bong Jung-Ho’s Snowpiercer), or a retooled version of “alien invasion” (e.g., Cixin Liu’s 2015 Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem), these stories all reflect a shift in focus from a technological-centred & human-centred story to a more eco- or world-centred story that explores wider and deeper existential questions. So, yes, science fiction today may appear less technologically imaginative; but it is certainly more sociologically astute, courageous and sophisticated. Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and editor of the growing collection of works by Hal Friesen, Craig Bowlsby, Krysia Anderson, Elizabeth Woods, Nina Munteanu, Randy McCharles and others writing works set in the ORU. As a publisher, she is working with Kyle Davidson, Jeff Doten, Sarah Trick, Jennifer Lott, Paula Johanson, Lynn Perkins and Yukari Yamamoto in re-inventing publishing through Reality Skimming Press. Lynda holds three degrees and works as Learning Technology Analyst and manager of the Learn Tech support team at Simon Fraser University. She teaches part-time at BCIT.

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and editor of the growing collection of works by Hal Friesen, Craig Bowlsby, Krysia Anderson, Elizabeth Woods, Nina Munteanu, Randy McCharles and others writing works set in the ORU. As a publisher, she is working with Kyle Davidson, Jeff Doten, Sarah Trick, Jennifer Lott, Paula Johanson, Lynn Perkins and Yukari Yamamoto in re-inventing publishing through Reality Skimming Press. Lynda holds three degrees and works as Learning Technology Analyst and manager of the Learn Tech support team at Simon Fraser University. She teaches part-time at BCIT. Sarah Kades hung up her archaeology trowel and bid adieu to Traditional Knowledge facilitation to share her love of the natural world and happily-ever-afters. She writes literary romantic eco-fiction where nature, humour and love meet. She lives in Calgary, Canada with her family. Connect with Sarah on

Sarah Kades hung up her archaeology trowel and bid adieu to Traditional Knowledge facilitation to share her love of the natural world and happily-ever-afters. She writes literary romantic eco-fiction where nature, humour and love meet. She lives in Calgary, Canada with her family. Connect with Sarah on  Stephanie Johanson is the art director, assistant editor, and co-owner of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, publishing since 2003. She is an artist who has worked in a variety of media, though painting and soapstone carving are her passions. Stephanie paints realism with a hint of fantasy, often preferring landscapes as her subjects. Examples of her work can be viewed on the Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine website at

Stephanie Johanson is the art director, assistant editor, and co-owner of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, publishing since 2003. She is an artist who has worked in a variety of media, though painting and soapstone carving are her passions. Stephanie paints realism with a hint of fantasy, often preferring landscapes as her subjects. Examples of her work can be viewed on the Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine website at  Diane Walton is currently serving a life sentence as Managing Editor of On Spec Magazine, and loving every minute of it. She and her lovely and talented husband, Rick LeBlanc, share their rural Alberta home with three very entitled cats.

Diane Walton is currently serving a life sentence as Managing Editor of On Spec Magazine, and loving every minute of it. She and her lovely and talented husband, Rick LeBlanc, share their rural Alberta home with three very entitled cats.

I mentioned that the majority of my stories are science fiction (SF). SF is a literature of allegory and metaphor and deeply embedded in culture. It draws me because it is the literature of consequence exploring large issues faced by humankind. In a February 2013 interview in The Globe and Mail I described how by its very nature SF is a symbolic meditation on history itself and ultimately a literature of great vision: “Speaking for myself, and for the other women I know who read science fiction, the need is for good stories featuring intelligent women who are directed in some way to make a difference in the world…The heroism [of women] may manifest itself through co-operation and leadership in community, which is [often] different from their die-hard male counterparts who want to tackle the world on their own. Science fiction provides a new paradigm for heroism and a new definition of hero as it balances technology and science with human issues and needs.”

I mentioned that the majority of my stories are science fiction (SF). SF is a literature of allegory and metaphor and deeply embedded in culture. It draws me because it is the literature of consequence exploring large issues faced by humankind. In a February 2013 interview in The Globe and Mail I described how by its very nature SF is a symbolic meditation on history itself and ultimately a literature of great vision: “Speaking for myself, and for the other women I know who read science fiction, the need is for good stories featuring intelligent women who are directed in some way to make a difference in the world…The heroism [of women] may manifest itself through co-operation and leadership in community, which is [often] different from their die-hard male counterparts who want to tackle the world on their own. Science fiction provides a new paradigm for heroism and a new definition of hero as it balances technology and science with human issues and needs.” We’ve progressed from the biological to the mechanical to the purely mental, from the natural world to a manufactured world to a virtual world, writes philosopher and writer Charles Eisenstein. According to Carolyn Merchant, professor at UC Berkley, early scientists of the 1600s used metaphor, rhetoric, and myth to develop a new method of interrogating nature as “part of a larger project to create a new method that would allow humanity to control and dominate the natural world.”

We’ve progressed from the biological to the mechanical to the purely mental, from the natural world to a manufactured world to a virtual world, writes philosopher and writer Charles Eisenstein. According to Carolyn Merchant, professor at UC Berkley, early scientists of the 1600s used metaphor, rhetoric, and myth to develop a new method of interrogating nature as “part of a larger project to create a new method that would allow humanity to control and dominate the natural world.” Competition is a natural reaction based on distrust—of both the environment and of the “other”—both aspects of “self” (as part) separated from “self” (as whole). The greed for more than is sustainable reflects an urgent fear of failure and a sense of being separate. It ultimately perpetuates actions dominated by self-interest and is the harbinger of “the Tragedy of the Commons”.

Competition is a natural reaction based on distrust—of both the environment and of the “other”—both aspects of “self” (as part) separated from “self” (as whole). The greed for more than is sustainable reflects an urgent fear of failure and a sense of being separate. It ultimately perpetuates actions dominated by self-interest and is the harbinger of “the Tragedy of the Commons”. Examples of creative cooperatives exist throughout the world, offering an alternative to the traditional model of competition. Cultural creatives are changing the world, Ruche tells us. These creatives, while being community-oriented with an awareness of planet-wide issues, honor and embody feminine values, such as empathy, solidarity, spiritual and personal development, and relationships. Mechanisms include reciprocity, trust, communication, fairness, and a group-sense of belonging. I give examples in my upcoming book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press, due in Spring 2016.

Examples of creative cooperatives exist throughout the world, offering an alternative to the traditional model of competition. Cultural creatives are changing the world, Ruche tells us. These creatives, while being community-oriented with an awareness of planet-wide issues, honor and embody feminine values, such as empathy, solidarity, spiritual and personal development, and relationships. Mechanisms include reciprocity, trust, communication, fairness, and a group-sense of belonging. I give examples in my upcoming book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press, due in Spring 2016.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit