From the rolling Prairies I ascended up the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Alberta. As I neared the mountains, they seemed to cut the sky with jagged peaks of steely grey. Rugged and unabashedly wild, they teased my spirits into flight.

.

The Rockies are such a wonder! I found myself thinking—well, wishing—that I had a geologist sitting in the passenger seat (instead of my companions Toulouse, Mouse and a car full of plants), telling me all about these stately mountains and their formations. All that folding, thrusting, scraping and eroding! So fascinating!

.

.

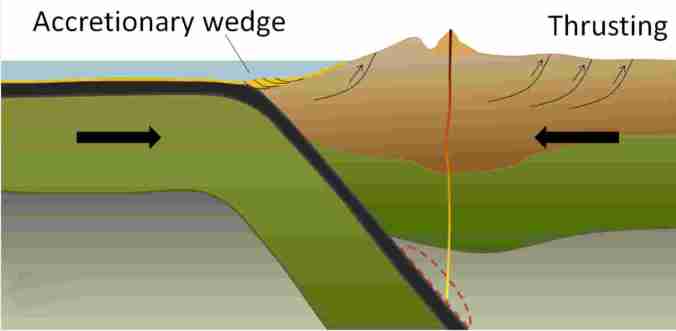

I did some research into The Canadian Rocky Mountains and discovered that they were formed through a combination of subduction and thrust faulting with an oceanic plate subducting beneath the North American plate.

.

.

The Canadian Rocky Mountains were originally part of an ancient shallow sea half a billion years ago and formed from pieces of continental crust over a billion years old during an intense period of plate tectonic activity. Their jagged peaks of mostly sedimentary limestone (originally part of the continental shelf) and shale (originally part of the deeper ocean waters) belonged to an ancient sea floor; during the Paleozoic Era (~5-2 hundred million years ago), western North America lay beneath a shallow sea, depositing kilometers of limestone and dolomite.

.

.

The current Canadian Rocky Mountains were raised by the Cordilleran Orogeny, a process of mountain-building when tectonic plates started colliding ~ 200 million years ago during much of the Mesozoic Era, which extends over 187 million years from the beginning of the Triassic (252 Ma) to the end of the Cretaceous (65 Ma). This era, I’m told, was a particularly important period for the geology of western Canada. During the plate and land mass collisions, ancient seabed layers were scraped, folded and thrust upwards (through a process called thrust faulting). As plates converged, entire sheets of sedimentary rock were slowly pushed on top of other sheets, creating a situation where older rocks lie on top of younger ones.

.

.

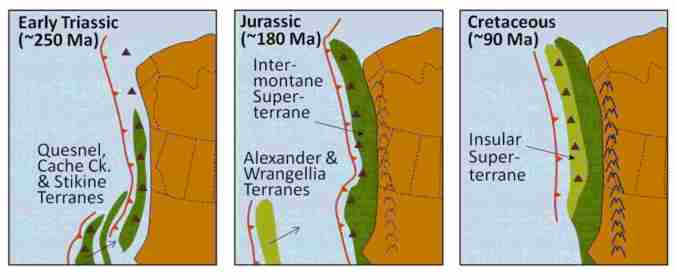

According to Earle and Panchuk, several continental collisions occurred along the west coast over the Mesozoic, resulting in the formation of the Rocky Mountains and the accretion (addition) of much of British Columbia’s land mass. Starting in the early Triassic (~250 Ma) through to the Cretaceous Period (~90 Ma), continued subduction sent several continental terranes (land masses) colliding into and accreting to the western edge of North America. The Quesnel, Cache Creek, and Stikine Terranes formed the Intermontane Superterrane, which now forms BC’s interior plateau between the Rockies and the Coast Range. A hundred million years later, during the Jurassic Period, a pair of terranes—Alexander and Wrangellia—collided with the west coast to form most of Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii as well as part of Alaska. During the Cenozoic Era, more terranes accreted with the western edge of North America.

.

.

In the Jurassic Period, the Intermontane Superterrane acted like a giant bulldozer, pushing, folding, and thrusting the existing Proterozoic and Paleozoic west coast sediments eastward and upward to form the Rocky Mountains. The same process continued into the Cretaceous as the Insular Superterrane collided with North America and pushed the Intermontane Superterrane farther east.

.

.

Canadian geologist/author Ben Gadd explains the Canadian Rocky Mountain building through the metaphor of a rug being pushed on a hardwood floor: the rug bunches up and forms wrinkles (mountains). In Canada, the subduction (downward movement) of an oceanic tectonic plate and the terranes (slabs of land) smashing into the continent are the feet pushing the rug, the ancestral rocks are the rug, and the Canadian Shield in the middle of the continent is the hardwood floor. The Rockies, writes Gadd, were like Tibet: a high plateau, 6,000 metres above sea level. Then, in the last 60 million years, glaciers—creeping forward at 50 feet per year—stripped away the high rocks, revealing the ancestral rocks beneath and carving out steep U-shaped valleys to form the current landscape of the Rockies: jagged peaks of soft sedimentary limestone and shale overlooking steep gorges and valleys. You can watch an excellent video of the 200-million-year formation of the Rocky Mountains by Spark.

.

.

When I stopped in Canmore, Alberta, for the night, I found all the hotels solidly booked, except for a few very expensive rooms in high end hotels. It was the weekend of the Calgary Stampede and the crowds had spilled out this far, I was told. I also acknowledged that I was plum in the middle of tourist season too. But I was dead tired and it would be dark soon; so, I bit the bullet and booked an expensive room in an expensive hotel. I recalled that I was repeating my mother’s trip across Canada to settle in Victoria many years ago; she’d also driven through here in her old Datsun, brim with plants, like my Benny, and stopped in Canmore for the night. Only, she found very reasonable accommodations when she came through over four decades ago. Canmore is located in the front ranges of the Rockies, with a wonderful view of the Three Sisters and Ha Ling Peak from my hotel room.

.

.

.

I gave Banff and Lake Louise a miss and opted for a breakfast at some remote viewpoint after crossing the border into British Columbia. As I ate my cereal from the tailgate of my car, I felt a strange but lovely warm joy spread through me like a deep soothing balm.

I was home…

.

.

I stopped at Faeder Lake, on the western side of Yoho National Park, with a view of the Ottertail Range and Mount Vaux. Faeder Lake’s clear tourquise water—a result of fine particles of rock dust called glacial flour—enticed me for a swim.

I stopped briefly for lunch in Golden in the Rocky Mountain Trench. The Rocky Mountain Trench is a long and deep valley walled by sedimentary, volcanic and igneous rock that extends some 1,500 km north south, spanning from Montana through British Columbia. The Trench is sometimes referred to as the “Valley of a Thousand Peaks” because of the towering mountain ranges on either side: the Rocky Mountains to the east and the Columbia, Omineca and Cassiar mountains to the west.

.

.

The Trench is a large fault—a crack in the Earth’s crust—and bordered along much of its length by smaller faults. Major structural features resulted from the shifting and thrusting of tectonic plates of the crust during the early Cenozoic Era (65 million years ago) during mountain formation discussed above. The ridges of fractured crust pulled apart and the land in between dropped, creating the floor of the Trench. Major rivers that flow through the trench include the Fraser, Liard, Peace and Columbia rivers.

.

The Rocky Mountain Trench features in two of my books: A Diary in the Age of Water (Inanna Publications) and upcoming novel Thalweg. In both novels, which take place in the near future, the trench has been flooded to create a giant inland sea to serve as water reservoir and hydropower to the USA. You can read an excerpt in my article “A Diary in the Age of Water: The Rocky Mountain Trench Inland Sea.” The article also talks about the original 1960s NAWAPA plan by Parsons Engineering to flood the trench to service dry sections of the US by diverting and storing massive amounts of Canadian water. Proponents are still talking about it!

.

.

I entered Glacier National Park, driving through several snow & avalanche sheds at Rogers Pass, in the heart of the Selkirk Range of the Columbia Mountains. This part of the drive was spectacular as mountains towered close and steep above me like sky scrapers, fanning out as the bright green vegetation crept resolutely up their scree slopes.

.

.

The highway followed the Illecillewaet River as it wound southwest to Arrow Lake from it’s the glaciers east. I soon reached Revelstoke National Park and stopped at the Giant Cedars Boardwalk Trail, located about 30 km east of Revelstoke, between the Monashee Mountains, west, and the Selkirk Range, east.

.

.

The Giant Cedars Boardwalk Park is a rare inland temperate rainforest ecosystem, receiving significant precipitation from Pacific weather systems that rise over the Columbia Mountains and dump here. It is a lush and humid old-growth forest with rich diversity of plant and animal life that resembles a coastal rainforest. Dominated by Western Red Cedars and Western Hemlocks—with some Douglas fir, paper birch and Bigleaf maple—the forest floor is a rich understory of salal, devil’s club, several berry shrubs and a diversity of ferns—oak fern, sword fern, and licorice fern. All was covered with a dense carpet of mosses, lichens, liverworts and fungi.

.

.

I followed the boardwalk through a cathedral of towering trees, among ancient cedars, whose fibrous, thick trunks loomed high to pierce the sky. Some are over 500 years old. I found that one large cedar trunk beside the boardwalk was ‘smooth from loving’ as I leaned against it and stroked its bark, no longer fibrous but burnished smooth and shiny.

.

.

I reached Revelstoke just after 6 pm and, to celebrate, I booked a room at the Regent Hotel. After a walk through the ski resort town, alive with young tourists, I returned to the hotel restaurant, I treated myself to a celebratory salmon dinner with garlic mashed potatoes and mixed veggies. I even I had a dessert—Tiramisu with a cup of tea—and went to bed sated, happy and tired. As soon as my head hit the pillow, I was in dreamland.

.

.

.

The next day, I descended southwest from the Selkirk Range, passing through Kamloops and then arriving at Merritt, in the heart of the Nicola Valley, an area of dry forests, grasslands, sagebrush, alpine meadows, and wetlands. This was range country, dry, golden and rolling with the peppery scent of sage. The most visible and dominant vegetation included big sage (Artemisia tridentata) and bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata) with the odd Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa) dotting the dry landscape.

.

.

From there, I drove south along the Coquihalla Highway in the Cascades Range to Hope, where I treated myself to an ice cream cone and ate it overlooking the mighty Fraser River. I followed the Fraser west to Vancouver, where it empties into the Pacific Ocean.

My last stop before reaching my good friend’s place in Ladner (where I would stay until I found my own place) was the Four Winds Brewery on Tilbury Road, where I bought a case of beer for the pizza we would share once I got there.

Home sweet home.

.

References:

Gadd, Ben. 2008. “Canadian Rockies Geology Road Tours.” Corax Press.

Earle, Steven and Karla Panchuk. 2019. “Physical Geology”, 2nd edition: Chapter 21: Geological History of Western Canada, 21.4, Western Canada during the Mesozoic.” BCcampus. OpenTextBC/Physical Geology

Munteanu, Nina. 2020. “A Diary in the Age of Water.” Inanna Publications, Toronto. 328 pp.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.