In this series of articles, I draw from key excerpts of my textbook on how to write fiction The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now! whose 26 chapters go from A to Z on the key aspects of writing good and meaningful fiction.

M is for Master the Metaphor & Other Things

During a brainstorming session, my business partner quizzed me on the major problems that writers face: “What are their Waterloos?” She was using metaphor to make a point. You don’t have to look very far to find examples; everyday speech is full of them: like “raining cats and dogs; “table leg”; and “old flame”.

Metaphor directly compares seemingly unrelated subjects. It is, therefore, considered more powerful than an analogy, which may acknowledge differences. Other rhetorical devices in the ‘metaphor family’ that involve comparison include metonymy, synecdoche, personification, simile, allegory and parable. While these share common attributes with metaphor, each compares in a different way.

The term synecdoche substitutes a part for a whole or a whole for a part (e.g., the expression “all hands on deck” refers to the men; or the expression “use your head” refers to your brain). Synecdoche is a common way to emphasize an important aspect of a character.

Metonymy uses one word to describe and represent another (e.g. the suits from Wall Street). Metonymy works by association whereas metaphor works through similarity.

Personification gives an idea, object or animal the qualities of a person (e.g., the darkness embraced her; the creek babbled over the rocks).

Similes can imply comparison (e.g., His mind is like a sword) or be explicit (e.g., His mind is sharp like a sword). This is what makes the simile such a useful tool to the writer: you can choose to be vague, letting the reader infer the relationship, or be direct.

Simile: His love was like a slow dance

Metaphor: Love danced in her heart

Allegory is an extended metaphor in which an object, person or action is equated with the meaning that lies outside the narrative. In other words, allegory has both a literal and a representative meaning.

The kinds of metaphor you use (extended metaphors particularly) rely a great deal on your narrative voice, the type of story you’re telling, and the language you’re using. Here are two from Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye:

His hair was bone white.

I got the drunk up [the stairs] somehow. He was eager to help but his legs were rubber.

The metaphor is often tied in to the overall theme or plot line of the story, providing tone to the story and sometimes foreshadowing.

N is for Now It’s Time for Revision

Ten things you should consider when revising your first (and subsequent) draft(s).

1. Let your work breathe: once you’ve completed your draft, set it aside for a while. This lets you make objective observations about your writing when you return.

2. Dig deep: now that you have the whole story before you, you can restructure plotlines, subplots, events and characters to best reflect your overall story. Don’t be afraid to remove large sections; you will likely add others. You may also merge two characters into one or add a character or change a character’s gender or age.

3. Take Inventory: it’s good to take stock of how each chapter contributes to plotline and theme; root out the inconsistencies as you relate the minutiae to the whole.

4. Highlight the Surges: some passages will stand out as being particularly stunning; pay attention to them in each chapter and apply their energy to the rest of your writing.

5. Purge & Unclutter: make a point of shortening everything; this forces you to use more succinct language, replacing adjectives and adverbs with power-verbs. Liken it to writing for a magazine with only so much space (check out Chapter U for more ideas). Doing this will tighten prose and make it more clear. Reading aloud, particularly dialogue, can help streamline your prose.

6. Point of view: this is the time to take stock of whether you’ve chosen the best point of view for the story. You may wish to experiment with different points of view at this stage and the results may surprise you.

7. Make a plot promise: given that you are essentially making a promise to your readers, it is advisable that you revisit that promise. Tie up your plot points; don’t leave any hanging unless you’re intentionally doing this, but be aware that readers don’t generally like it. Similarly, if you’ve written a scene that is lyrical, beautiful and compelling but doesn’t contribute to your plotline, nix it. But keep it for another story; chances are, it will work elsewhere. The trick is to file it where you can later find it.

8. Deepen your characters: the revision process is an ideal time to add subtle detail to your main characters. A nervous scratch of his beard, an absent twisting of the ring on her finger, the frequent use of a particular expression: all these can be worked in throughout the story, in your later drafts. Even minor characters can shine and be unique. When you paint your minor characters with more detail, you create a more three-dimensional tapestry for your main characters to walk through. This heightens realism in your story and involvement of your reader.

9. Write scenes: use the revision process to convert flat narrative into “scene” through dramatization. Narrative summaries read like lecture or polemic. They tend to be passive, slow, and less engaging. Scenes include action, tension and conflict, dialogue and physical movement.

10. Be concrete: Rosenfeld describes your novel as a world in which your reader enters and wants to stay in for a while. You make it easy for her by adding concrete details for her to envision and relate to. Ground your characters in vivid setting, rich but unobtrusive detail. Don’t abandon them to a generic and prosaic setting, drinking “beverages” and driving “vehicles” on “roads”; instead brighten up their lives by having them speeding along Highway 66 in a Mini Cooper, while sipping a Pinot Noir.

O is for Outline or Synopsis?

A synopsis is NOT an outline. Both are useful to the writer, yet each serves a very different purpose. An outline is a tool (usually just for the writer) that sketches plot items of a book. It provides a skeleton or framework of plot, people, places and their relationships to the storyline. It permits the writer to ultimately gauge scene, setting, and character depth or even determine whether a character is required (every character must have a reason to be in the book, usually to move the plot). To put it basically, the outline describes what happens when and to whom, while the synopsis includes why.

Elizabeth Lyon, author of The Sell Your Novel Toolkit, suggests that a synopsis should usually include these seven items:

• Theme

• Setting and Period

• Plot summary

• Character sketches

• Dialogue

• Emotional turning points

• Subplots

The theme, explains Lyons, “provides a rudder for an entire novel.” She suggests condensing it into one sentence or phrase: to have a friend you must be a friend; cooperation lies at the heart of evolution; love is the true source of human wealth; there’s no place like home. You can also portray your theme in a single word (e.g., forgiveness, revenge, trust, prejudice, evolution).

Lyon suggests that the plot summary is like a skeleton upon which to flesh out character and theme. Two things you need to consider are that 1) you must summarize the complete novel (beginning, middle and end) and 2) you should not confuse a plot summary (essentially an outline) with a synopsis, which incorporates more than plot. “The best-written and most impressive synopses,” says Lyon, “are those that make it clear that a story is character driven.” Lyon recommends that you limit your sketches to the main characters that drive principle theme in the story.

The first sentence of my synopsis of Collision with Paradise focuses on the main character:

When Genevieve Dubois, Zeta Corp’s hot shot starship pilot accepts a research mission aboard ZAC I to the mysterious planet Eos, she not only collides with her guilty past but with her own ultimate fantasy.

While the sentence conveys information about the plot, it is given from the viewpoint of a character’s motivations and feelings. The reader is informed at the outset that character development is at the heart of the story.

The emotional turning points are the focal events that are directly linked to the theme of the story. These are the “so what” parts of the story plot—where the character reaches an epiphany and, as a result, changes—and are ultimately linked to the climax of the story.

The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now! (Starfire World Syndicate) May 2009. Nominated for an Aurora Prix Award. Available through Chapters/Indigo, Amazon, The Book Depository, and Barnes & Noble.

The Fiction Writer is a digest of how-to’s in writing fiction and creative non-fiction by masters of the craft from over the last century. Packaged into 26 chapters of well-researched and easy to read instruction, novelist and teacher Nina Munteanu brings in entertaining real-life examples and practical exercises. The Fiction Writer will help you learn the basic, tried and true lessons of a professional writer: 1) how to craft a compelling story; 2) how to give editors and agents what they want’ and 3) how to maintain a winning attitude.

“…Like the good Doctor’s Tardis, The Fiction Writer is larger than it appears… Get Get Published, Write Now! right now.”

David Merchant, Creative Writing Instructor

Click here for more about my other guidebooks on writing.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

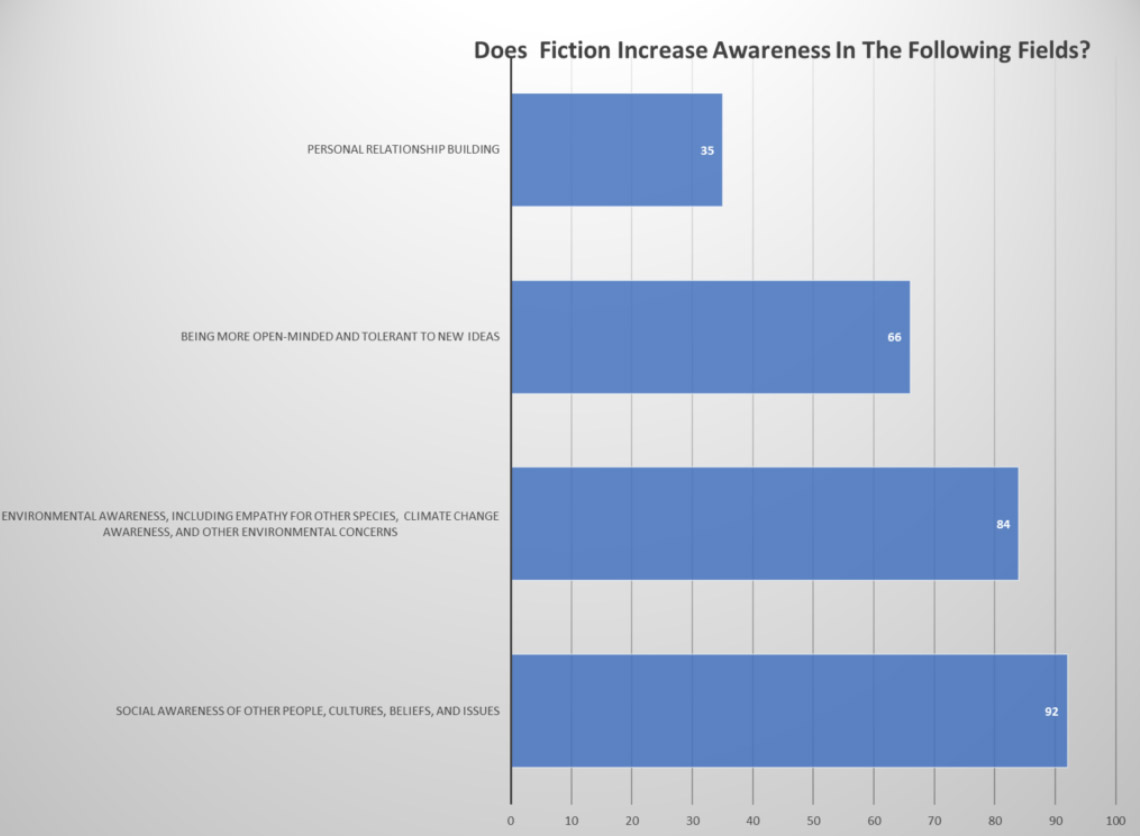

Some of the most impactful novels according to the readers surveyed include Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series.

Some of the most impactful novels according to the readers surveyed include Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series.

In my writing guidebook

In my writing guidebook  They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.  Environmental forces—such as weather, climate, forests, mountains, water systems—convey the mood and tone of both story and character. These environmental forces are not just part of the scenery. To a writer, they are devices used in plot, theme and premise. They may also be a compelling character, particularly in eco-fiction, climate-fiction, and speculative fiction. Dystopian fiction often explores a violent world of contrast between the affluent and vulnerable poor that often portrays the aftermath of economic and environmental collapse (e.g., Maddaddam Trilogy, The Windup Girl, Snowpiercer, Interstellar, Mad Max). In any fiction genre it is important to get the science right. Readers of fiction with strong environmental components, however, expect to learn as much from the potential reality as from the real science upon which the premise depends.

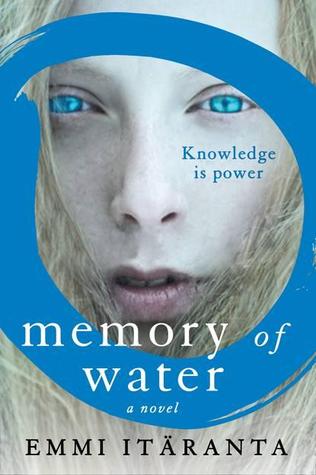

Environmental forces—such as weather, climate, forests, mountains, water systems—convey the mood and tone of both story and character. These environmental forces are not just part of the scenery. To a writer, they are devices used in plot, theme and premise. They may also be a compelling character, particularly in eco-fiction, climate-fiction, and speculative fiction. Dystopian fiction often explores a violent world of contrast between the affluent and vulnerable poor that often portrays the aftermath of economic and environmental collapse (e.g., Maddaddam Trilogy, The Windup Girl, Snowpiercer, Interstellar, Mad Max). In any fiction genre it is important to get the science right. Readers of fiction with strong environmental components, however, expect to learn as much from the potential reality as from the real science upon which the premise depends. Water is the most versatile of all elements … Water walks with the moon and embraces the earth, and it isn’t afraid to die in fire or live in air. When you step into it, it will be as close as your own skin, but if you hit it too hard, it will shatter you … Death is water’s close companion. The two cannot be separated, and neither can be separated from us, for they are what we are ultimately made of: the versatility of water, and the closeness of death. Water has no beginning and no end, but death has both. Death is both. Sometimes death travels hidden in water, and sometimes water will chase death away, but they go together always, in the world and in us.

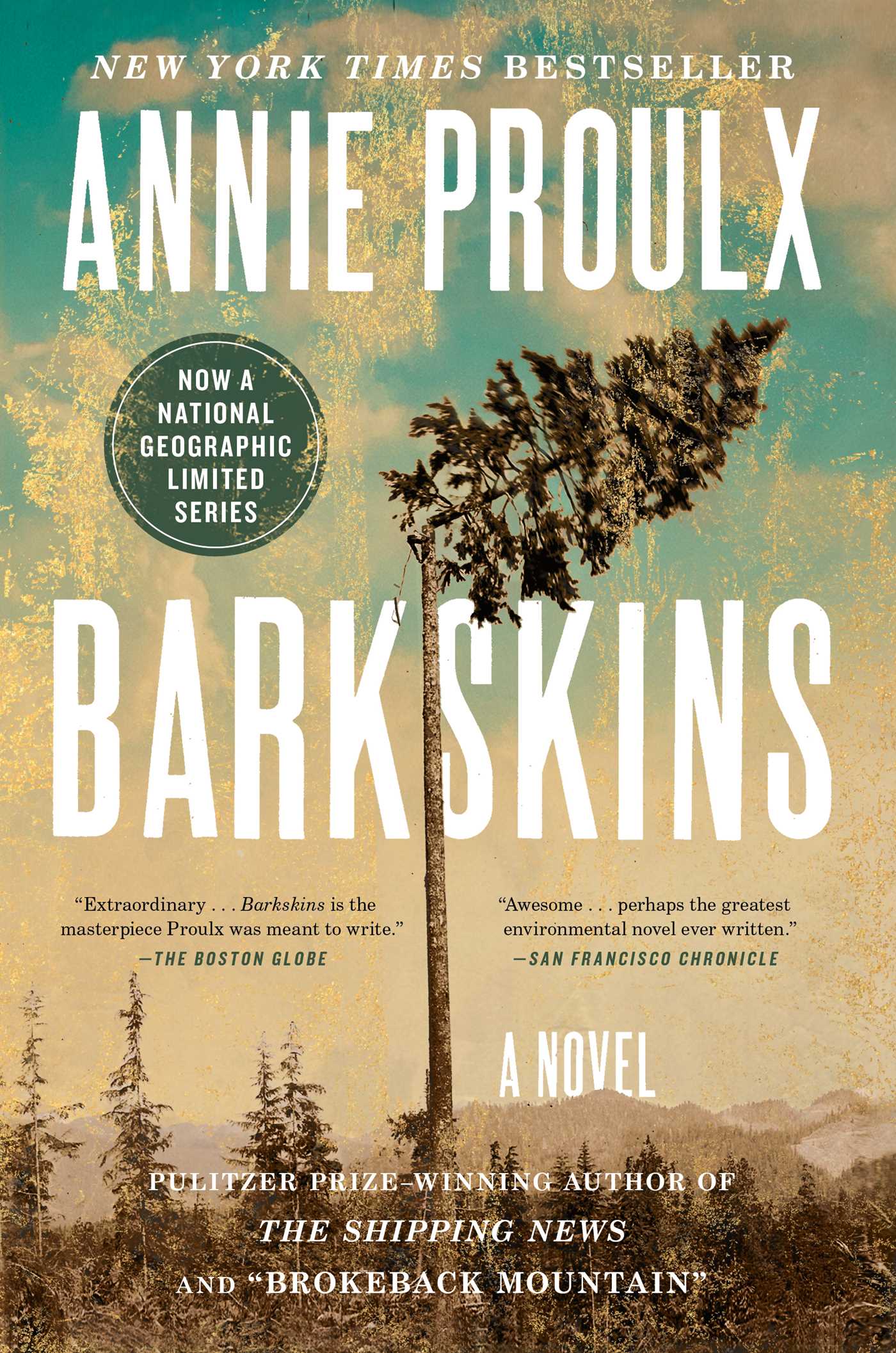

Water is the most versatile of all elements … Water walks with the moon and embraces the earth, and it isn’t afraid to die in fire or live in air. When you step into it, it will be as close as your own skin, but if you hit it too hard, it will shatter you … Death is water’s close companion. The two cannot be separated, and neither can be separated from us, for they are what we are ultimately made of: the versatility of water, and the closeness of death. Water has no beginning and no end, but death has both. Death is both. Sometimes death travels hidden in water, and sometimes water will chase death away, but they go together always, in the world and in us.  Annie Proulx opens her novel Barkskins with a scene in which René Sel and fellow barkskins (woodcutters) arrive from France in the late seventeenth century to the still pristine wilderness of Canada to settle, trade and accumulate wealth:

Annie Proulx opens her novel Barkskins with a scene in which René Sel and fellow barkskins (woodcutters) arrive from France in the late seventeenth century to the still pristine wilderness of Canada to settle, trade and accumulate wealth:

I write mostly eco-fiction. Even before it was known as eco-fiction, I was writing it. My first book—

I write mostly eco-fiction. Even before it was known as eco-fiction, I was writing it. My first book— Water has been used as a powerful archetype in many novels. In my latest novel,

Water has been used as a powerful archetype in many novels. In my latest novel,  In these examples the environmental aspect serves as symbol and metaphoric connection to theme. They can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchel’s Gone With the Wind; the white pine forests for the Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; The animals for Beatrix Potter of the Susan Wittig Albert series.

In these examples the environmental aspect serves as symbol and metaphoric connection to theme. They can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchel’s Gone With the Wind; the white pine forests for the Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; The animals for Beatrix Potter of the Susan Wittig Albert series.

Nina: I guess that every weed was once a native somewhere. I also agree that times are changing—faster than many of us are ready for, humans included. If you were to identify with an archetype, which would you choose?

Nina: I guess that every weed was once a native somewhere. I also agree that times are changing—faster than many of us are ready for, humans included. If you were to identify with an archetype, which would you choose?