I’ve been a coaching writers for over two decades. I help fiction and non-fiction writers get published. I teach courses on novel writing and tutor technical and scientific writers at the University of Toronto writing centres. I’ve helped with plot, theme, characterization, and setting. I’ve worked with writers on establishing directed narratives and clarifying content. When it comes to grammar and punctuation, there is one punctuation that students of writing all too often misuse, abuse, or outright ignore: the semi-colon. They really don’t get it…And I’m trying to change that.

Recently, Dena Bain Taylor (my former supervisor in the University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre), wrote a rousing post about this dear but often neglected and misused punctuation. It resonated with my experience and I just had to share it here:

The Sad Death of the Semi-Colon

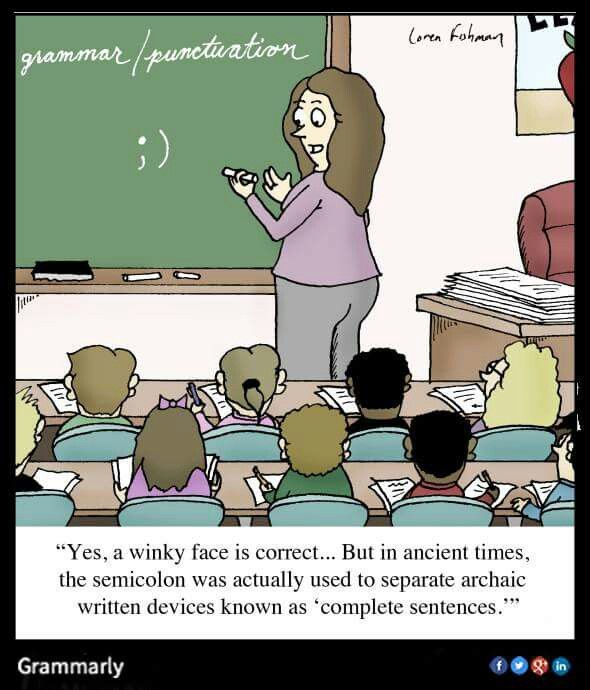

As you drown your lockdown sorrows in that last bottle of wine, spare a thought for the semi-colon. Its demise, slow and terrible, long predates the pandemic.

The semi-colon is a particularly elegant piece of punctuation and doesn’t deserve its fate. I can think of a number of emojis I’d happily consign to the dustbin if it meant saving the semi-colon.The elegance of the semi-colon lies in its ability to both join and separate. It is, after all, a combination of a period and a comma.

In its glory days, the semi-colon filled two main functions.

One was to join two independent clauses; in other words, you have two elements that could stand as separate sentences but their ideas come together to make a single point. These days, people often replace the semi-colon with a period, splitting the thought into two sentences. I can live with that. What I can’t live with is replacing the semi-colon with a comma.

Its other function is to separate elements in a list that themselves contain internal commas. See how much easier this is to read because of the semi-colons:

The breakfast menu included toast, eggs and bacon; refried rice, beans and tortillas; and coffee or juice.

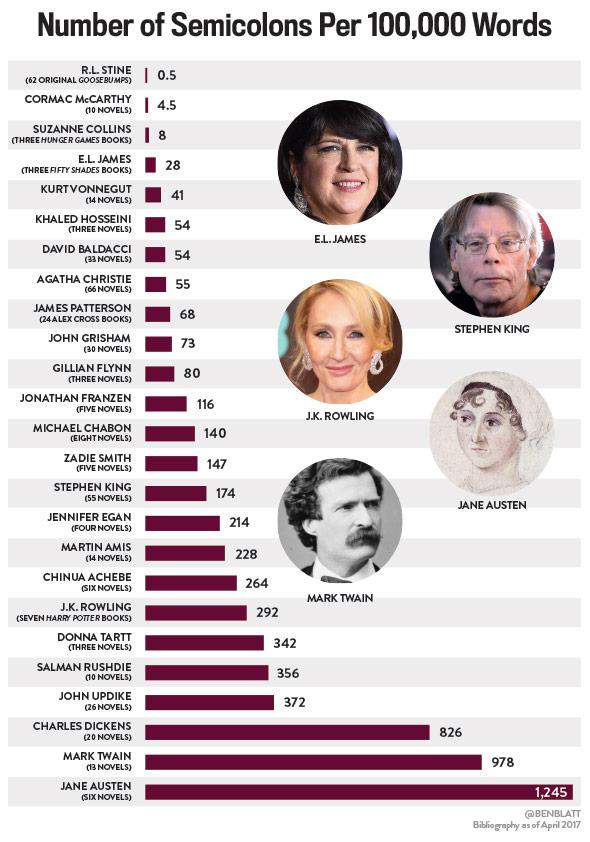

Some might say that “a semi-colon was used when a sentence could have been ended; but it wasn’t.” This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Some of you may recall Kurt Vonnegut’s scathing edict in his 2005 book A Man Without a Country to all would-be creative writers: “First Rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college.” This was followed by novelist John Irving’s pithy observation: “No one knows what they are anymore. If you’re not in the habit of reading nineteenth-century novels, you think that the author has killed a fruit fly directly above a comma—semicolons have become nothing but a distraction.” And yet, author Gordon Gravley tells us that “John Irving (once a student of Vonnegut) is quite liberal with semicolons; they cover the pages of his novels like acne on the face of a fast-food restaurant employee. He loves them.” Irving was, after all, the anti-Hemingway; he often used long sentences with subordinate clauses punctuated by semi-colons. Author John Pistelli gives Irving credit for his own love of the semicolon: “Insofar as I aspired to write fiction that felt as densely fated as [Irving’s], both complex and unified, it seemed useful to adopt the mark of punctuation that stood for complexity and unity.” Who’d have thought this innocuous hybrid of comma and colon would stir such vehement condemnation, confusion, and self-denial?

Of the semi-colon, Abraham Lincoln once wrote: I must say I have a great respect for the semicolon; it’s a very useful little chap. While Cormac McCarthy noted simply: No semicolons. Even George Orwell proclaimed: I had decided about this time that the semicolon is an unnecessary stop and that I would write my next book without one.

I submit that it is the semi-colon’s very quality of eluding an exact definition that gives it so much versatility. That is its power over both period and comma; like Schrödinger’s cat, it is neither, yet both. The true power of the semi-colon—aside from its quantum properties—lies in how it brings two otherwise independent thoughts together (that may share something of significance even if elusive) to elegantly compare or contrast. And to create wonderful irony. Wonderful and subtle irony!

“Semi-colons signal, rather than shout, a relationship … A semi-colon is a compliment from the writer to the reader. It says: ‘I don’t have to draw you a picture; a hint will do.’”

George Will, Washington Post columnist

In the thread that followed Dena Bain Taylor’s article, one writer shared that his fiction editor had admonished him for using the semi-colon, proclaming that: “It’s generally not the practice in fiction.” Nabokov, Chekhov, and Woolf certainly ignored that prognosis. I have noted its use in many other excellent works of fiction; I use it in my own fiction.

Responding to Bain Taylor’s Linked In post, John Collins, strategic and creative marketer, wrote: “A comma gives you pause; a semi-colon leaves you room to breathe. The world is full of LOLs and BRBs, but there is still room for the intentioned difference that timely breathing engenders. And because its use is becoming rarer, it becomes even more meaningful and impactful if wielded properly.”

Returning to John Irving, here is what he wrote in an essay on Dickens:

It was relatively late in his life that he began to give public readings, yet his language was consistently written to be read aloud—the use of repetition, of refrains; the rich, descriptive lists that accompany a newly introduced character or place; the abundance of punctuation. Dickens overpunctuates; he makes long and potentially difficult sentences slower but easier to read—as if his punctuation is a form of stage direction, when reading aloud; or as if he is aware that many of his readers were reading his novels in serial form and needed nearly constant reminding. He is a master of that device for making short sentences seem long, and long sentences readable—the semicolon!

–John Irving, The King of the Novel

Author John Pistelli attempts an explanation for the evolution of the growing controversy of the semi-colon, which was certainly used more in classic literature: “Dickens used commas and semicolons to give direction to breath, a script for performance. Over the course of the last century, however, we have split text from speech, literature from orature. Poetry and fiction may trace their roots to song and stage, but modern technology and reading habits have removed the voice from literature. We read silently, whether in public or private.” Despite this, Pistelli draws on the work of Christian Thorne, to extol how the semi-colon’s “push-pull suggests the tense relationship of the clauses it both marries and divorces”:

It is through punctuation marks that even ordinary writing overcomes its own ingrained positivism, its tendency to reduce the world to rubble, static things and discrete events. Commas introduce relation to the simplest sentences, as periods do disjunction. Dashes and semicolons establish relation and disjunction at once; they sunder even as they join, which makes them the typographical face of dialectical thought.

Christian Thorne

I have often used not so much typography but topography to metaphorically describe the three dimensional face of narrative: how verbs, nouns and prepositions conspire with idea to create relief; how sentences–passive / active, short or long–flow into larger relief. If words and sentences are the bones of our thoughts, then punctuation is the connective tissue of their meaning in a three-dimensional world.

With that last remark, I urge you to rethink this under-used tool. Include it in your Writer’s Toolkit and join the great writers and thinkers—from unknown to famous—who have masterfully embraced the semi-colon:

“Celebrate failure; it means you took a risk.”—Anonymous

“I think; therefore I am.”—Rene Descartes

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”—Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

“The decline of literature indictes the decline of a nation. Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.”—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“Love does not dominate; it cultivates.”—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Journalist, urbanist and futurist Greg Lindsay gave a rousing keynote speech to start the conference. Greg spoke about the future of cities, technology, and mobility. He is the director of applied research at NewCities and director of strategy at its mobility offshoot CoMotion. He also co-authored the international bestseller

Journalist, urbanist and futurist Greg Lindsay gave a rousing keynote speech to start the conference. Greg spoke about the future of cities, technology, and mobility. He is the director of applied research at NewCities and director of strategy at its mobility offshoot CoMotion. He also co-authored the international bestseller

We then discussed future implications of water scarcity (and geopolitical conflict) and some of the things individuals and communities can do. Much of the talk drew from my recent book

We then discussed future implications of water scarcity (and geopolitical conflict) and some of the things individuals and communities can do. Much of the talk drew from my recent book

Research what you’ve found on the Internet; find out more about something you’ve observed. For instance, why does the willow have such a shaggy bark? Why do alders grow so well near the edges of streams? What role do sowbugs play in the ecosystem? What do squirrels eat? What is that bird doing on my lawn? Start a phenology study (how something changes over the seasons). Keep tabs on the birds you see and what they’re doing. You can find several examples of mine in the links below.

Research what you’ve found on the Internet; find out more about something you’ve observed. For instance, why does the willow have such a shaggy bark? Why do alders grow so well near the edges of streams? What role do sowbugs play in the ecosystem? What do squirrels eat? What is that bird doing on my lawn? Start a phenology study (how something changes over the seasons). Keep tabs on the birds you see and what they’re doing. You can find several examples of mine in the links below.

Expressive writing — whether in the form of journaling, blogging, writing letters, memoir or fiction — improves health. Over the past twenty years, a growing body of literature has shown beneficial effects of writing about traumatic, emotional and stressful events on physical and emotional health. In control experiments with college students, Pennebaker and Beall (1986) demonstrated that college students who wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings for only 15 minutes over four consecutive days, experienced significant health benefits four months later. Long term benefits of expressive writing include improved lung and liver function, reduced blood pressure, reduced depression, improved functioning memory, sporting performance and greater psychological well-being. The kind of writing that heals, however, must link the trauma or deep event with the emotions and feelings they generated. Simply writing as catharsis won’t do.

Expressive writing — whether in the form of journaling, blogging, writing letters, memoir or fiction — improves health. Over the past twenty years, a growing body of literature has shown beneficial effects of writing about traumatic, emotional and stressful events on physical and emotional health. In control experiments with college students, Pennebaker and Beall (1986) demonstrated that college students who wrote about their deepest thoughts and feelings for only 15 minutes over four consecutive days, experienced significant health benefits four months later. Long term benefits of expressive writing include improved lung and liver function, reduced blood pressure, reduced depression, improved functioning memory, sporting performance and greater psychological well-being. The kind of writing that heals, however, must link the trauma or deep event with the emotions and feelings they generated. Simply writing as catharsis won’t do. In Chapter K of my writing guidebook

In Chapter K of my writing guidebook

According to

According to

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

Notice how the use of active verbs also unclutters sentences and makes them more succinct and accurate. This was achieved not only by choosing active verbs but power-verbs that more accurately portray the mood and feel of the action. Most of the verbs used in the Passive column are weak and can be interpreted in many ways; words such as “walk” “were” “sit” and “stare”; each of these verbs begs the question ‘how’, hence the inevitable adverb. So we end up with “walk slowly” “were now struggling” “sit up” and “stare angrily.” When activated with power-verbs, we end up with “sidle” “struggled” “rear up” and “glared”—all more succinctly and accurately conveying a mood and feeling behind the action.

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.