“We shall break down all walls—to let the green wind blow free from end to end—across the earth.”

I-330 in ‘We’

Just last week, I read for the first time Yevgeny Zamyatin’s masterpiece We. My first thought upon finishing it was: why have I waited until now to read it? I’m rather embarrassed to say that I’d only heard of its existence recently during some research I’d conducted on another article. The novel, written in 1920, decades before Brave New World and 1984 (two novels it is often compared to and which I read when I was a budding writer, long ago), was suppressed in Russia. It has remained in the shadows of these two works since. Mesmerized by Zamyatin’s fluid metaphoric prose, I read it in a few days.

I usually savour a good novel, but this one compelled me to take it in like an infusion.

The book jacket of the Harper Voyager edition provides the following tagline and description:

“Before Brave New World…before 1984…there was…We. In the One State of the great Benefactor, there are no individuals, only numbers. Life is an ongoing process of mathematical precision, a perfectly balanced equation. Primitive passions and instincts have been subdued. Even nature has been defeated, banished behind the Green Wall…”

.

We is told through a series of entries by the main protagonist D-503, mathematician and chief engineer of the Integral (the ship that will take humanity to space). The novel takes place in a glass-enclosed Panopticon-like city of straight lines, and scientifically managed using Taylor’s principles of scientific management. No one knows or cares about the outside environment from which they have been separated. Citizens in the totalitarian society of One State are regulated hourly by the Table of Hours, and ruled by the ‘Benefactor’ who dispenses order through arcane methods such as The Machine (a modern ‘guillotine’ of sorts that literally liquidates its victim, reducing them to a puff of smoke and a pool of water), The Cube, The Gas Bell, and the ruthless precision and vigilance of the Bureau of Guardians. All this is “sublime, magnificent, noble, elevated, crystally pure,” writes D-503, because “it protects our unfreedom—that is, our happiness.” In the foreword to the Penguin edition of We, New Yorker journalist Masha Gessen reminds us that, “Zamyatin imagined [We] twenty years before Nazi Germany began sanitized, industrial mass murder of people who had been reduced to numbers.”

Citizens subsist on synthetic food and march in step in fours to the anthem of the One State played through loudspeakers. There is no marriage, and every week citizens are given a “sex hour” and provided a pink slip to let them draw down the shades of their glass apartment. Every year, on Unanimity Day, the Benefactor is re-elected by the entire population, through an open (not secret) vote that is naturally unanimous—given the singular “we” nature of the population.

.

On Zamyatin’s novel, Michael Brendan Dougherty writes that, “Equality is enforced, to the point of disfiguring the physically beautiful. Beauty–as well as its companion, art–are a kind of heresy in the One State, because ‘to be original means to distinguish yourself from others. It follows that to be original is to violate the principle of equality.”

According to Mirra Ginsburg, who translated the book into English in 1972, Zamyatin and his book explores the oppression of two principles of human existence: eternal change and the individual’s freedom to choose, to want, to create according to his own need and his own will.

In some ways, Zamyatin’s satire is as much about our separation from the chaos, ever-evolving and functional diversity of nature as it is about our separation from the unruly thoughts and emotions of the individual. Both are feared and must be defeated, controlled and commodified (I refer to Foucault’s concept of biopolitics).

D-503 writes in his journal: “we have extracted electricity from the amorous whisper of the waves; we have transformed the savage, foam-spitting beast into a domestic animal; and in the same way we have tamed and harnessed the once wild element of poetry. Today poetry is no longer the idle, impudent whistling of a nightingale; poetry is civic service, poetry is useful.”

D-503’s thirteenth entry takes place on a particularly foggy day. When new friend I-330 ‘innocently’ asks him if he likes the fog, he responds, “I hate the fog. I’m afraid of it.” To this, I-330 says, “That means you love it. You are afraid of it because it is stronger than you; you hate it because you are afraid of it; you love it because you cannot subdue it to your will. Only the unsubduable can be loved.”

.

D-503 appears content as a ‘number’ within a larger unity of regimentation and draws comfort from a universe of logic and rationality, represented by the predictive precision of mathematics. For example, he is disturbed by the concept of the square root of -1, the basis for imaginary numbers (imagination being reviled by the One State and which will eventually be lobotomized out of citizens through the mandatory Great Operation). The spaceship’s name Integral represents the integration of the grandiose cosmic equation following the Newtonian hegemony of a machine universe.

.

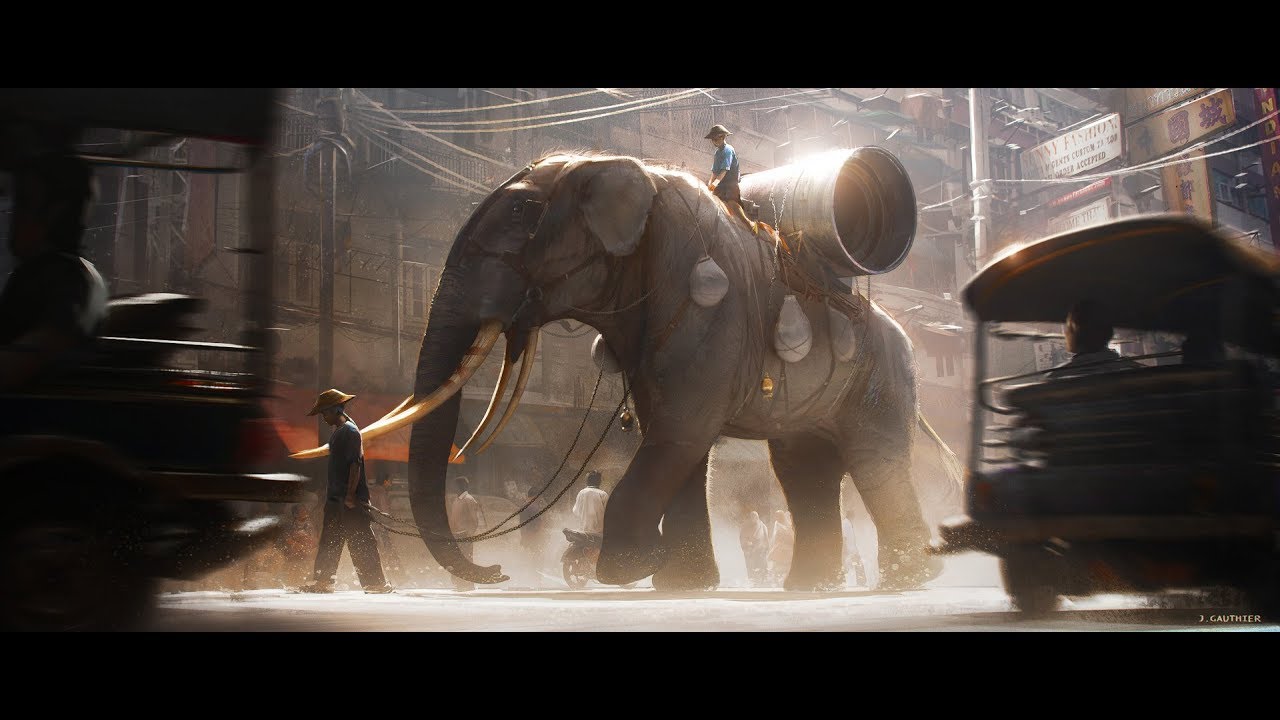

In the following scene in which D-503 watches men work on the spacecraft Integral—itself likened to a giant slumbering machine-human—I am reminded of an iconic scene from Fritz Lang’s 1927 Metropolis:

“I watched the men below move in regular, rapid rhythm…bending, unbending, turning like the levers of a single huge machine. Tubes glittered in their hands; with fire they sliced the glass walls, angles, ribs, brackets. I saw transparent glass monster cranes rolling slowly along glass rails, turning and bending as obediently as the men, delivering their loads into the bowels of the Integral. And all of this was one: humanized machines, perfect men…Measured movements; firmly round, ruddy cheeks; mirror-smooth brows, untroubled by the madness of thought.”

.

All is indeed sublime … Until he meets I-330, Zamyatin’s unruly heroine who is determined to change D-503’s perspective—and his vacuous state of dutiful ‘happiness.’ She is, of course, a member of an underground resistance, Mephi, bent on overthrowing the One State. I-330 is the herald of change and wishes to use D-503’s connection to the Integral to incite a revolution. In a particularly pithy scene, I-330 challenges D-503’s complacent logic with mathematics to make her point:

“Do you realise that what you are suggesting is revolution?” [says D-503]

“Of course, it’s revolution. Why not?”

“Because there can’t be a revolution. Our revolution was the last and there can never be another. Everybody knows that.”

“My dear, you’re a mathematician: tell me, which is the last number?”

“But that’s absurd. Numbers are infinite. There can’t be a last one.”

“Then why do you talk about the last revolution? There is no final revolution. Revolutions are infinite.”

Confident, powerful and heroic, the liberated I-330 is clearly the driving force of change and the philosophical voice of Zamyatin’s central theme. Her competent manipulations within the system successfully orchestrates a revolution which includes interfering with the unanimous vote, breaching the Green Wall, and braving torture to the end–all the kind of feats usually relegated to a male protagonist in novels of that era. It all starts with a tiny crime and escalates from there. Early in the novel, I-330 lures D-503 to the Medical Office, where the Mephi doctor gives them a sick card so they can play hooky from work. D-503 doesn’t even realize how I-330 has so completely caught him. His description of the facility and the officer is telling:

“A glass room filled with golden fog. Glass ceilings, colored bottles, jars. Wires. Bluish sparks in tubes. And a tiny man, the thinnest I had ever seen. All of him seemed cut out of paper, and no matter which way he turned, there was nothing but a profile, sharply honed: the nose a sharp blade, lips like scissors.”

Biblical references appear throughout We, the One State likened to ‘Paradise’, D-503 to the naïve ‘Adam’, I-330 to the herald temptress ‘Eve’, and S-4711 to the clever snake, with his ‘double-curved body,’ who turns out to be a double-agent. The revolutionary organization named Mephi appears to be after Mephistopheles, who rebelled against Heaven and ‘paradise.’ While these similarities suggest a criticism of organized religion, the novel clearly embodies so much more. It is also so much more than a political statement. Journalist and translator Mirra Ginsburg calls We “a complex philosophical novel of endless subtlety and nuance, allusion and reflections. It is also a profoundly moving human tragedy and a study in the variety of human loves … And, though the people are nameless ‘numbers,’ they are never schematic figures; each is an individual, convincingly and movingly alive.”

Zamyatin wrote We years before the word “totalitarianism” appeared in political speech and he predicted its defining condition: the destruction of the individual. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt argued that totalitarianism was a novel oppression: previous tyrants demanded obedience; but obedience was not enough for the totalitarian regime, which sought to occupy the entire person and obliterate their very core. As the self disintegrates, humans—like worker bees—fuse into what Arendt called “one man of gigantic dimensions.” Zamyatin’s word for it was: “we.”

“In a world without personal boundaries, a world without deviation, serendipity, difference, a world without ‘I,’ there can be no ‘us.’ The ‘we’ of We is a mass rather than a community of people. Arendt wrote about loneliness as the defining condition of totalitarianism. She drew a distinction between loneliness—a sense of isolation—and solitude, a condition necessary for thinking. One could be lonely in a crowd. But in Zamyatin’s world of transparent houses and uniform lives, one could not have solitude.”

Masha Gessen on the ‘we’ of We

.

Comparison of We with Brave New World and 1984

As I was reading We, I could not help comparing it to George Orwell’s 1984, written over twenty-five years later. Similarities in plot and theme abound, right down to the inverted language of the government: the tyrant is the ‘Benefactor’ just as Orwell’s Ministry of Love is where dissidents are tortured or Oceana’s paradoxical ministry slogans–Freedom is Slavery … Ignorance is Strength … War is Peace. Three years before the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1949, Orwell reviewed We and compared it with Huxley’s Brave New World, published in 1932:

“The first thing anyone would notice about We is the fact—never pointed out, I believe—that Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World must be partly derived from it. Both books deal with the rebellion of the primitive human spirit against a rationalised, mechanised, painless world, and both stories are supposed to take place about six hundred years hence. The atmosphere of the two books is similar, and it is roughly speaking the same kind of society that is being described though Huxley’s book shows less political awareness and is more influenced by recent biological and psychological theories.”

George Orwell, 1946 review of “We”

.

While Orwell criticizes Zamyatin’s book as being “less well put together—it has a rather weak and episodic plot which is too complex to summarize,” he praises it for making a political point that according to him Huxley’s book lacks (for the record, I disagree with Orwell on this; Huxley’s political point is just more subtle, just as his characters are). Orwell found Zamyatin’s We more convincing and relevant than Huxley’s Brave New World given that in the technocratic totalitarian state of We “many of the ancient human instincts are still there,” not eradicated by eugenics and medication (such as soma). Citing the many executions in Zamyatin’s Utopia, all taking place publicly in the presence of the Benefactor and accompanied by “triumphal odes recited by the official poets”, Orwell suggested that, “It is this intuitive grasp of the irrational side of totalitarianism—human sacrifice, cruelty as an end in itself, the worship of a Leader who is credited with divine attributes—that makes Zamyatin’s book superior to Huxley’s.”

.

Noam Chomsky considered We more perceptive than Brave New World or 1984, the latter which he called “wooden and obvious” despite clever and original nuances such as “newspeak,” which provided a medium for the world view and principles of Ingsoc and to make other forms of thought impossible (“it’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words…” says Syme in 1984). I agree with Chomsky. Next to the bleak and hopeless polemic of Nineteen Eighty-Four, We is less dialectic, more visceral, it is full-bodied, ribald, tender, emotional and immediate. But above all, it is hopeful. Again, Mirra Ginsburg says it best:

“We is more multifaceted, less hopeless than Orwell’s 1984, written more than twenty-five years later and directly influenced by Zamyatin’s novel. Despite its tragic ending, We still carries a note of hope. Despite the rout of the rebellion, ‘there is still fighting in the western parts of the city.’ Many ‘numbers’ have escaped beyond the Wall. Those who died were not destroyed as human beings—they died fighting and unsubmissive. And though the hero is reduced to an obedient automaton, certain that “Reason” and static order will prevail, though the woman he loved briefly and was forced into betraying dies (as do the poets and rebels she led), the woman who loves him, who is gentle and tender, is safe beyond the Wall. She will bear his child in freedom. And the Wall has been proved vulnerable after all. It has been breached—and surely will be breached again.”

Mirra Ginsburg, on ‘We’

.

It may seem like a tragic end, particularly for the two main protagonists: D-503 is lobotomized into an obedient drone of the sterile system and betrays his lover; I-330 is no doubt liquidated under The Machine, after refusing to submit and betray her comrades. To the end, she is the messenger of hope and resilience and the force for removal of barriers. The wall does come down–even if for just a moment towards the end of the book–and the Green Wind blows furiously through the land, bringing with it birds and other creatures previously unseen along with the scent of change.

Zamyatin’s We is ultimately a cautionary tale on the folly of logic without love and a profound call to connect to our natural world to nurture our souls. Before he is rendered inert by the Great Operation, D-503 gives O-90 a child. It is no mistake that O-90, who tenderly and selflessly loved and refused to surrender her child to the One State, makes it outside (with the help of I-330) into the natural world. Driven by love (not rationality), she represents the future.

.

About the Author and His Work

Yevgeny Zamyatin was born in 1884 in Lebedyan, Russia, which according to Mirra Ginsburg was “one of the most colourful towns in the heart of the Russian black-earth belt, some two hundred miles southeast of Moscow—a region of fertile fields, of ancient churches and monasteries, of country fairs, gypsies and swindlers, nuns and innkeepers, buxom Russian beauties, and merchants who made and lost millions overnight.”

Showing influences by Jerome K. Jerome’s 1891 short story The New Utopia and H.G. Wells’ 1899 novel When the Sleeper Wakes and the Expressionist works of Kandinsky, Yevgeny Zamyatin created We in 1920. His political satire was denied publication in Russia but Zamyatin managed to smuggle the manuscript to New York, where it was published in English in 1924 by Dutton. Mirra Ginsburg writes of Zamyatin’s death in 1937: “[it] went unmentioned in the Soviet press. Like the rebellious poet in We, and like so many of the greatest Russian poets and writers of the twentieth century, he was literally ‘liquidated’—reduced to nonbeing. His name was deleted from literary histories and for decades he has been unknown in his homeland.” The first publication of We in Russia had to wait until 1988—after more than sixty years of suppression—when glasnost resulted in it appearing alongside Orwell’s 1984.

Zamyatin called We “my most jesting and most serious work.” His credo, written in 1921 in I am Afraid, proclaimed that “true literature can exist only where it is created, not by diligent and trustworthy officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics.”

We directly inspired the following literary works: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, Invitation to a Beheading by Vladimir Nabokov, Anthem by Ayn Rand, Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell, Player Piano by Kurt Vonnegut, Logan’s Run by William F. Nolan and George Clayton, This Perfect Day by Ira Levin, and The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin.

The Penguin classics edition describes We as “the archetype of the modern dystopia, or anti-Utopia: a great prose poem detailing the fate that might befall us all if we surrender our individual selves to some collective dream of technology and fail in the vigilance that is the price of freedom.”

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Craig Russell begins his eco-thriller Fragment with a TV interview of glaciologist Kate Sexsmith in Scott Base Antarctica. The interview is interrupted by what turns out to be four runaway glaciers that have avalanched into the back of the Ross Ice Shelf and a fragment the size of Switzerland surges out into the open sea. Hence the title: Fragment.

Craig Russell begins his eco-thriller Fragment with a TV interview of glaciologist Kate Sexsmith in Scott Base Antarctica. The interview is interrupted by what turns out to be four runaway glaciers that have avalanched into the back of the Ross Ice Shelf and a fragment the size of Switzerland surges out into the open sea. Hence the title: Fragment.

Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 biopunk science fiction novel The Windup Girl occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of ag-biotech multinational giants such as AgriGen, RedStar, and PurCal—predatory companies who have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing and sterilizing genetic manipulations. The story’s premise could very easily be described as “what would happen if Monsanto got its way?”

Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 biopunk science fiction novel The Windup Girl occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of ag-biotech multinational giants such as AgriGen, RedStar, and PurCal—predatory companies who have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing and sterilizing genetic manipulations. The story’s premise could very easily be described as “what would happen if Monsanto got its way?” It’s difficult not to always be aware of those high walls and the pressure of the water beyond. Difficult not to think of the City of Divine Beings as anything other than a disaster waiting to happen. But the Thais are stubborn and have fought to keep their revered city of Krung Thep from drowning. With coal-burning pumps and leveed labor and a deep faith in the visionary leadership of their Chakri Dynasty they have so far kept at bay that thing which has swallowed New York and Rangoon, Mumbai and New Orleans.

It’s difficult not to always be aware of those high walls and the pressure of the water beyond. Difficult not to think of the City of Divine Beings as anything other than a disaster waiting to happen. But the Thais are stubborn and have fought to keep their revered city of Krung Thep from drowning. With coal-burning pumps and leveed labor and a deep faith in the visionary leadership of their Chakri Dynasty they have so far kept at bay that thing which has swallowed New York and Rangoon, Mumbai and New Orleans.