.

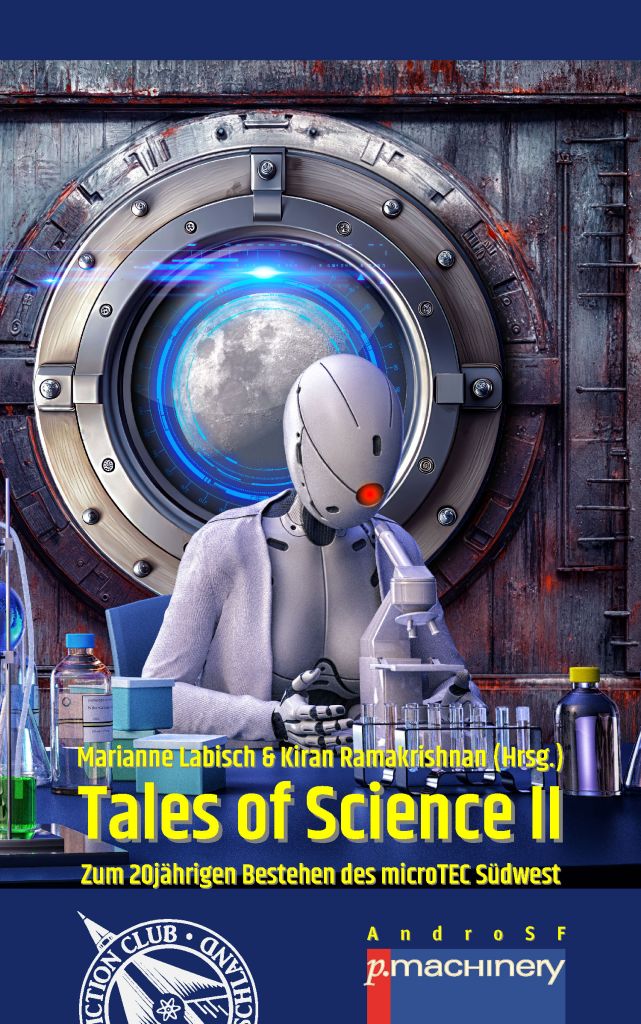

A few weeks ago, I looked into my mail box and found my contributor’s copy of “Tales of Science II” Anthology (edited by Marianne Labisch & Kiran Ramakrishnan) with my short story Die Polywasser-Gleichung (“The Polywater Equation”) inside. Beaming, I did a little dance because the anthology was marvelous looking! And it was all in German! (My mother is German, so I could actually read it; bonus!).

This science-fiction anthology, for which I was invited to contribute, collected seventeen short stories, all based on sound science. Here’s how the book jacket blurb (translated from German) describes the anthology:

.

It’s all just fiction. Someone made it up; it has nothing to do with reality, right? Well, in this anthology, there’s at least a grain of truth in all the stories, because scientific sponsors collaborated with authors. Here, they looked into the future based on current research What does such an experiment look like? See for yourself what the authors and scientific sponsors have come up with: about finding a way to communicate with out descendants, finding the ideal partner, conveying human emotions to an AI, strange water phenomena [that’s my story], unexpected research findings, lonely bots, and much more. The occasion for this experiment is the 20th anniversary of the microsystems technology cluster microTEC Südwest e. V.

(cover image and illustrations by Mario Franke and Uli Benkick)

.

In our initial correspondence, editor Marianne Labisch mentioned that they were “looking for short stories by scientists based on their research but ‘spun on’ to create a science fiction story;” she knew I was a limnologist and was hoping I would contribute something about water. I was glad to oblige her, having some ideas whirling in my head already. That is how “The Polywater Equation” (Die Polywasser-Gleichung) was born.

I’d been thinking of writing something that drew on my earlier research on patterns of colonization by periphyton (attached algae, mostly diatoms) in streams using concepts of fluid mechanics. Elements that worked themselves into the story and the main character, herself a limnologist, reflected some aspects of my own conflicts as a scientist interpreting algal and water data (you have to read the story to figure that out).

.

My Work with Periphyton

As I mentioned, the short story drew on my scientific work, which you can read about in the scientific journal Hydrobiologia. I was studying the community structure of periphyton (attached algae) that settled on surfaces in freshwater streams. My study involved placing glass slides in various locations in my control and experimental streams and in various orientations (parallel or facing the current), exposing them to colonizing algae. What I didn’t expect to see was that the community colonized the slides in a non-random way. What resulted was a scientific paper entitled “the effect of current on the distribution of diatoms settling on submerged glass slides.”

.

.

For more details of my work with periphyton, you can go to my article called Championing Change. How all this connects to the concept of polywater is something you need to read in the story itself.

.

The Phenomenon of Polywater

The phenomenon started well before the 1960s, with a 19th century theory by Lord Kelvin (for a detailed account see The Rise and Fall of Polywater in Distillations Magazine). Kelvin had found that individual water droplets evaporated faster than water in a bowl. He also noticed that water in a glass tube evaporated even more slowly. This suggested to Kelvin that the curvature of the water’s surface affected how quickly it evaporated.

.

.

In the 1960s, Nikolai Fedyakin picked up on Lord Kelvin’s work at the Kostroma Technological Institute and through careful experimentation, concluded that the liquid at the bottom of the glass tube was denser than ordinary water and published his findings. Boris Deryagin, director of the Institute of Physical Chemistry in Moscow, was intrigued and his team confirmed that the substance at the bottom of the glass tube was denser and thicker than ordinary water and had additional anomalous properties. This phase of water had a thick, gel-like consistency; it also had a higher stability, like a polymer, over bulk water. It demonstrated a lower freezing point, a higher boiling point, and much higher density and viscosity than ordinary water. It expanded more than ordinary water when heated and bent light differently. Deryagin became convinced that this “modified water” was the most thermodynamically stable form of water and that any water that came into contact with it would become modified as well. In 1966, Deryagin shared his work in a paper entitled “Effects of Lyophile Surfaces on the Properties of Boundary Liquid Films.” British scientist Brian Pethica confirmed Deryagin’s findings with his own experiments—calling the odd liquid “anomalous water”—and published in Nature. In 1969, Ellis Lippincott and colleagues published their work using spectroscopic evidence of this anomalous water, showing that it was arranged in a honeycomb-shaped network, making a polymer of water—and dubbed it “polywater.” Scientists proposed that instead of the weak Van der Waals forces that normally draw water molecules together, the molecules of ‘polywater’ were locked in place by stronger bonds, catalyzed somehow by the nature of the surface they were adjacent to.

.

.

This sparked both excitement and fear in the scientific community, press and the public. Industrialists soon came up with ways to exploit this strange state of water such as an industrial lubricant or a way to desalinate seawater. Scientists further argued for the natural existence of ‘polywater’ in small quantities by suggesting that this form of water was responsible for the ability of winter wheat seeds to survive in frozen ground and how animals can lower their body temperature below zero degrees Celsius without freezing.

When one scientist discounted the phenomenon and blamed it on contamination by the experimenters’ own sweat, the significance of the results was abandoned in the Kuddelmuddel of scientific embarrassment. By 1973 ‘polywater’ was considered a joke and an example of ‘pathological science.’ This, despite earlier work by Henniker and Szent-Györgyi, which showed that water organized itself close to surfaces such as cell membranes. Forty years later Gerald Pollack at the University of Washington identified a fourth phase of water, an interfacial water zone that was more stable, more viscous and more ordered, and, according to biochemist Martin Chaplin of South Bank University, also hydrophobic, stiffer, more slippery and thermally more stable. How was this not polywater?

.

The Polywater Equation

In my story, which takes place in Berlin, 2045, retired limnologist Professor Engel grapples with a new catastrophic water phenomenon that looks suspiciously like the original 1960s polywater incident:

The first known case of polywater occurred on June 19, 2044 in Newark, United States. Housewife Doris Buchanan charged into the local Water Department office on Broad Street with a complaint that her faucet had clogged up with some kind of pollutant. She claimed that the faucet just coughed up a blob of gel that dangled like clear snot out of the spout and refused to drop. Where was her water? she demanded. She’d paid her bill. But when she showed them her small gel sample, there was only plain liquid water in her sample jar. They sent her home and logged the incident as a prank. But then over fifty turbines of the combined Niagara power plants in New York and Ontario ground to a halt as everything went to gel; a third of the state and province went dark. That was soon followed by a near disaster at the Pickering Nuclear Generating Station in Ajax, Ontario when the cooling water inside a reactor vessel gummed up, and the fuel rods—immersed in gel instead of cooling water—came dangerously close to overheating, with potentially catastrophic results. Luckily, the gel state didn’t last and all went back to normal again.

If you read German, you can pick up a copy of the anthology in Dussmann das KulturKaufhaus or Thalia, both located in Berlin but also available through their online outlets. You’ll have to wait to read the English version; like polywater, it’s not out yet.

.

.

References:

Chaplin, Martin. 2015. “Interfacial water and water-gas interfaces.” Online: “Water Structure and Science”: http://www1.lsbu.ac.uk/water/interfacial_water.html

Chaplin, Martin. 2015. “Anomalous properties of water.” Online: “Water Structure and Science: http://www1.lsbu.ac.uk/water/water_anomalies.html

Henniker, J.C. 1949. “The depth of the surface zone of a liquid”. Rev. Mod. Phys. 21(2): 322–341.

Kelderman, Keene, et. al. 2022. “The Clean Water Act at 50: Promises Half Kept at the Half-Century Mark.” Environmental Integrity Project (EIP). March 17. 75pp.

Munteanu, N. & E. J. Maly, 1981. The effect of current on the distribution of diatoms settling on submerged glass slides. Hydrobiologia 78: 273–282.

Munteanu, Nina. 2016. “Water Is…The Meaning of Water.” Pixl Press, Delta, BC. 584 pp.

Pollack, Gerald. 2013. “The Fourth Phase of Water: Beyond Solid, Liquid and Vapor.” Ebner & Sons Publishers, Seattle WA. 357 pp.

Ramirez, Ainissa. 2020. “The Rise and Fall of Polywater.” Distillations Magazine, February 25, 2020.

Szent-Györgyi, A. 1960. “Introduction to a Supramolecular Biology.” Academic Press, New York. 135 pp.

Roemer, Stephen C., Kyle D. Hoagland, and James R. Rosowski. 1984. “Development of a freshwater periphyton community as influenced by diatom mucilages.” Can. J. Bot. 62: 1799-1813.

Schwenk, Theodor. 1996. “Sensitive Chaos.” Rudolf Steiner Press, London. 232 pp.

Szent-Györgyi, A. 1960. “Introduction to a Supramolecular Biology.” Academic Press, New York. 135 pp.

Wilkens, Andreas, Michael Jacobi, Wolfram Schwenk. 2005. “Understanding Water”. Floris Books, Edinburgh. 107 pp.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

In 1963 science fiction writer Kurt Vonnegut used the fictionalized concept of ice-IX—a crystalline polymorph of ice that remains stable at room temperature—in his novel Cat’s Cradle. Ice-nine was a form of water so stable that it never melted and would crystallize all water it touched. It was the Ebola of water…

In 1963 science fiction writer Kurt Vonnegut used the fictionalized concept of ice-IX—a crystalline polymorph of ice that remains stable at room temperature—in his novel Cat’s Cradle. Ice-nine was a form of water so stable that it never melted and would crystallize all water it touched. It was the Ebola of water…

The media spread a panic about polywater-contaminated oceans of “jelly” aka Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle.

The media spread a panic about polywater-contaminated oceans of “jelly” aka Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle.