I started writing and drawing as soon as I could hold a pencil. Even before I could read, I wanted to become a “paperback writer” like in the old Beatles song.

It was an incredible moment of clarity for me and despite being challenged by my stern and unimaginative primary school teacher, who kept trying to corral me into being “normal”, I wasn’t going to let anyone stem my creativity and eccentric — if not wayward — approach to literature, language and writing. I was a little brat and I knew it. She and I didn’t exactly get along. But I did okay and, despite her acidic commentary, Miss House awarded me some A’s and B’s…

I wrote some fan fiction but quickly found my own creations far more interesting and less limiting.

As a teenager, I wrote, directed and recorded “radio plays” with my sister. When we weren’t bursting into riotous laughter, it was actually pretty good. She and I shared a bedroom in the back of the house and at bedtime we opened our doors of imagination to a cast of thousands. We fed each other wild stories of space travel, adventure and intrigue, whispering and giggling well into the dark night, long after our parents were snoring in their beds.

Those days scintillated with liberating originality, excitement and joy.

(Photo: Nina Munteanu and sister Doina Maria Munteanu at Grouse Mountain, BC)

I also enjoyed animation and drew several cartoon strips, peopled with crazy characters. I dreamt of writing graphic novels like Green Lantern and Spiderman. My hero was science fiction author and futurist, Ray Bradbury; I vowed to write profoundly stirring tales like he did.

I had found what excites me — my passion for telling stories—and I’d inadvertently stumbled upon an important piece of the secret formula for success: 1) having discovered my passion, I decided on a goal; 2) I found and wished to emulate a “hero” who’d achieved that goal and therefore had a “case study”; 3) I applied myself to the pursuit of my goal. Oops … the third one, well … it went downhill from there … Life got in the way.

I grew up.

Well, that, and the environment intervened. In several ways. It started with my parents. Recognizing my talent and interest in the fine arts (I was good in visual arts), they pushed me to get a fine arts degree in university and go into teaching or advertizing. They didn’t see fiction writing as a viable career or a strength of mine (I was lousy at spelling and, despite my ability to tell stories and my love for graphic novels, I didn’t read books much). I can still remember my father’s lecture to me about how perfect the teaching or nursing profession was for me. I wasn’t enamored by either. The second blow to my author-ego came in the form of a school “interest-ability” test, meant to prepare us for our career decisions. I remember the test consisting of an IQ portion (spatial, English and math), and a psychology portion (including problem-solving and scenarios meant to tease out our affinity for a particular career). Secretly harboring my paperback novelist dream, I filled out my forms with great excitement. I still remember the deflating results, which suggested that I was best suited to be a sergeant in the army. “Writing” as a career barely made it on the graph, and scored well below “computer programmer” and “mechanic”; none of which interested me.

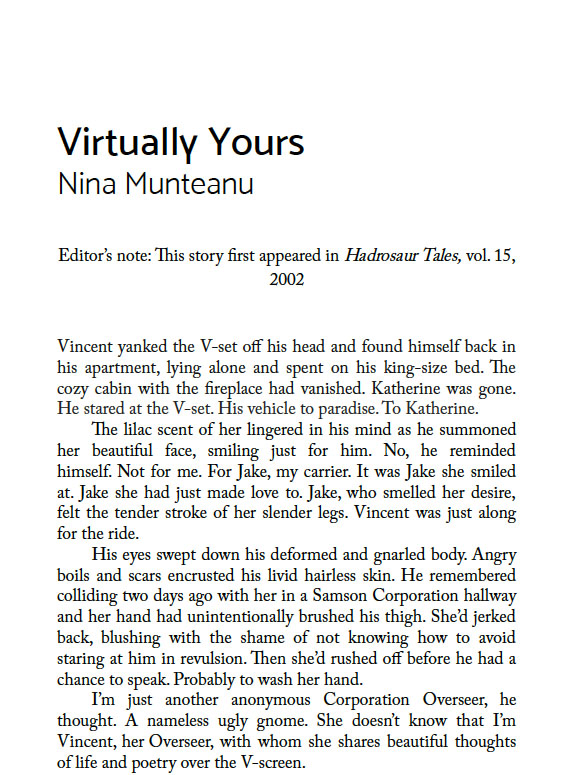

I got involved in the environmental movement, while quietly holding my dream of being a paperback novelist close to my heart. I got several degrees in ecology and consulted for various companies to help protect the environment. I wrote a lot in those days, although it was more about the ecology of creeks and about industrial pollution. But my passion for writing fiction continued to simmer. Magazines started publishing my articles—my first sale was to Shared Vision Magazine in 1995 on environmental citizenship—and my published articles became my entrance into the world of fiction. Once I began publishing fiction stories—my first short fiction sale was “Arc of Time” to Armchair Aesthete in 2002—I never looked back.

Eventually, I was publishing a novel and several short stories every year. My fiction most often focused on environmental issues, humanity’s relationship with the natural world, and how we reconcile our reliance on technology with our respect for the natural world.

Throughout my writer’s journey, and particularly early in my journey, I weathered the threshold guardians, tricksters and shadows: friends and family who called what I did a hobby, something I did just to pass the time; people who didn’t believe in me, envied my drive or simply thought I was wasting my time; even industry scammers who preyed on my dreams and wanted my money for nothing in return; and ultimately my own fears and frustrations on query after query and rejection after rejection. Throughout it all, I never stopped dreaming.

I’ve travelled through Europe, Africa, parts of Asia, and Australia. I raised a family and lived all over Canada from the Pacific to the Atlantic coast. I worked as a barista, shopkeeper and science lab instructor, then as environmental consultant, writing instructor and writing coach. During these wonderful life-adventures, I never stopped writing.

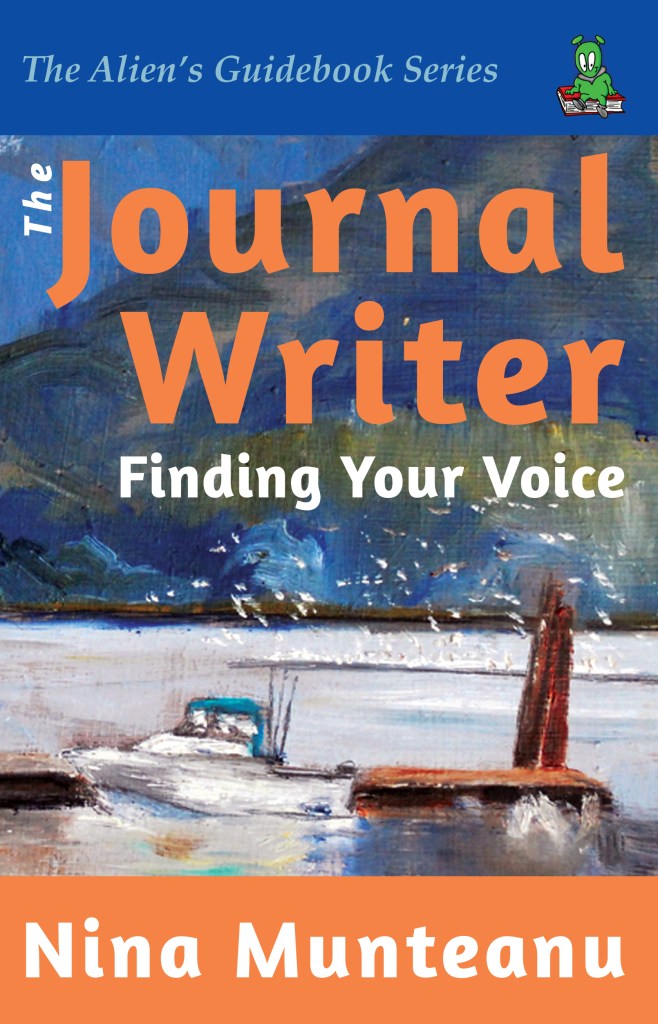

To date, I have written and sold over three dozen eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy novels, non-fiction books, short stories and articles. I have sold short stories to magazines in Canada and the U.S. with translations and reprints in Israel, Poland, Greece, and Romania. My short fiction has appeared in Neo-Opsis Science Fiction Magazine, Chiaroscuro, subTerrain, Apex Magazine, Metastellar, and several anthologies. I’ve seen my short stories nominated for the Aurora Prix Award (Canada’s premier award for writing science fiction and fantasy) and the Foundation of Speculative Fiction Fountain Award. Recognition for my work includes the Midwest Book Review Reader’s Choice Award, finalist for Foreword Magazine’s Book of the Year Award, the SLF Fountain Award, and The Delta Optimist Reviewers Choice Award.

I’ve published nine novels so far with nominations for the Aurora Prix, Foreword Magazine Book of the Year (several times), and various Reader’s Choice awards. My non-fiction book “Water Is…” (Pixl Press)—a scientific study and personal journey as limnologist, mother, and teacher—was Margaret Atwood’s pick in 2016 in the New York Times ‘The Year in Reading.’ My recent eco-novel released in 2020 by Inanna Publications “A Diary in the Age of Water“—about four generations of women and their relationship to water in a rapidly changing world—was a silver medalist for the Literary Titan Award, the Bronze winner of Foreword Magazine’s Book of the Year in 2020, longlisted for the Miramichi Review’s ‘Very Best Book of the Year Award,’ and a finalist for the 2021 International Book Award. Reviewers have described it as “lyrical…thought-provoking…unique and captivating…insightful…profound and brilliant…unsettling and yet deliciously readable…” One reviewer described it as a “a bit of a hybrid” and the writer “a risk taker”—which I quite liked. Another reviewer acknowledged that this was not a book for everyone and yet she found it “strangely compelling.”—which I found delicious.

It’s been twenty years since I seriously started my writing career with my first publication in 1995; my work is now recognized and translated throughout the world and I frequently get writing commissions from reputable magazines and publications. I am also frequently invited for speaking engagements and radio/podcast/TV interviews about my science and my writing. In short, I’ve come home; I’d taken a rather long detour but I’ve acquired some tools along the way. It’s been and continues to be a wonderful and exciting journey; and part of what made it so was that I never stopped dreaming and writing.

“…If you have nothing at all to create, then perhaps you create yourself…”

Carl Jung

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.