Here is my current list of 30 favourite eco-fiction novels and short story collections that have impacted me, and incited me to think, to feel and to act.

Flight Behavior is a multi-layered metaphoric study of “flight” in all its iterations: as movement, flow, change, transition, beauty and transcendence. Flight Behavior isn’t so much about climate change and its effects and its continued denial as it is about our perceptions and the actions that rise from them: the motives that drive denial and belief. When Dellarobia questions Cub, her farmer husband, “Why would we believe Johnny Midgeon about something scientific, and not the scientists?” he responds, “Johnny Midgeon gives the weather report.” Kingsolver writes: “and Dellarobia saw her life pass before her eyes, contained in the small enclosure of this logic.”

.

The Overstory follows the life-stories of nine characters and their journey with trees–and ultimately their shared conflict with corporate capitalist America. At the heart of The Overstory is the pivotal life of botanist Patricia Westerford, who will inspire movement. Westerford is a shy introvert who discovers that trees communicate, learn, trade goods and services—and have intelligence. When she shares her discovery, she is ridiculed by her peers and loses her position at the university. What follows is a fractal story of trees with spirit, soul, and timeless societies–and their human avatars.

.

The Maddaddam Trilogy is a work of speculative dystopian fiction that explores the premise of genetic experimentation and pharmaceutical engineering gone awry. On a larger scale the cautionary trilogy examines where the addiction to vanity, greed, and power may lead. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy explores a world where everything from sex to learning translates to power and ownership. The dark poetry of Atwood’s smart and edgy slice-of-life commentary is a poignant treatise on our dysfunctional society. Atwood accurately captures a growing zeitgeist that has lost the need for words like honor, integrity, compassion, humility, forgiveness, respect, and love in its vocabulary. And she has projected this trend into an alarmingly probable future. This is subversive eco-fiction at its best.

.

Annihilation is a science fiction eco-thriller that explores humanity’s impulse to self-destruct within a natural world of living ‘alien’ profusion. Annihilation is a bizarre exploration of how our own mutating mental states and self-destructive tendencies reflect a larger paradigm of creative-destruction—a hallmark of ecological succession, change, and overall resilience. VanderMeer masters the technique of weaving the bizarre intricacies of ecological relationship, into a meaningful tapestry of powerful interconnection. Bizarre but real biological mechanisms such as epigenetically-fluid DNA drive aspects of the story’s transcendent qualities of destruction and reconstruction. On one level Annihilation acts as parable to humanity’s cancerous destruction of what is ‘normal’ (through climate change and habitat destruction); on another, it explores how destruction and creation are two sides of a coin.

.

Barkskins chronicles two wood cutters who arrive from the slums of Paris to Canada in 1693 and their descendants over 300 years of deforestation in North America. Proulx weaves generational stories of two settler families into a crucible of terrible greed and tragic irony. The bleak impressions by immigrants of a harsh environment crawling with pests underlies the combative mindset of the settlers who wish only to conquer and seize what they can of a presumed infinite resource. From the arrival of the Europeans in pristine forest to their destruction under the veil of global warming, Proulx lays out a saga of human-environmental interaction and consequence that lingers with the aftertaste of a bitter wine.

.

Memory of Water is a work of speculative fiction about a post-climate change world of sea level rise. Symbols of water as shapeshifter archetype and its omnipotent life- and death-giving associations flow throughout the story, from the ‘fishfires’ in the northern skies to the painted blue circles on the doors of water criminals about to die. Water couples to main character Tea Master Noria, to explore consequences of commodification and exploitation. Teamaster Noria Kaitio guards its secrets; she alone knows the location of the hidden water source, coveted by the new government. Told in the literary fiction style of emotional nuances, Itäranta’s lyrical narrative follows a deceptively quiet yet tense pace that builds like a slow tide into compelling crisis and a poignant end.

.

The Broken Earth Trilogy is a fantasy trilogy set in a far-future Earth devastated by periodic cataclysmic storms known as ‘seasons.’ These apocalyptic events last over generations, remaking the world and its inhabitants each time. Giant floating crystals called Obelisks suggest an advanced prior civilization. The first book of the trilogy introduces Essun, an Orogene—a person gifted with the ability to draw magical power from the Earth such as quelling earthquakes. The trilogy focuses on the dangers of marginalization, oppression, and misuse of power. Jemison’s cautionary dystopia explores the consequence of the inhumane profiteering of those who are marginalized and commodified.

.

The Windup Girl is a work of mundane science fiction that occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of predatory ag-biotech multinational giants that have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing genetic manipulations. The rivalry between Thailand’s Minister of Trade and Minister of the Environment represents the central conflict of the novel, reflecting the current global conflict of neoliberal promotion of globalization and unaccountable exploitation with the forces of sustainability and environmental protection. Given the setting, both are extreme and there appears no middle ground for a balanced existence using responsible and sustainable means. The Windup Girl, Emiko, who represents the future, is precariously poised.

.

Parable of the Sower is a science fiction dystopian novel set in 21stcentury America where civilization has collapsed due to climate change, wealth inequality and greed. Parable of the Soweris both a coming-of-age story and cautionary allegorical tale of race, gender and power. Told through journal entries, the novel follows the life of young Lauren Oya Olamina—cursed with hyperempathy—and her perilous journey to find and create a new home. What starts as a fight to survive inspires in Lauren a new vision of the world and gives birth to a new faith based on science: Earthseed. Written in 1993, this prescient novel and its sequel Parable of the Talent speak too clearly about the consequences of “making America Great Again.”

.

The Water Knife is set in the near-future in the drought-stricken American southwest, where corrupt state-corporations have supplanted the foundering national government. Water is the new gold—to barter, steal, and murder for. Corporations have formed militias and shut down borders to climate refugees, fomenting an ecology of poverty and tragedy. Massive resorts—arcadias—constructed across the parched landscape, flaunt their water-wealth in the face of exploited workers and gross ecological disparity. Water is controlled by corrupt gangsters and “water knives” who cleverly navigate the mercurial nature of water rights in a world where “haves” hydrate and “have nots” die of thirst.

.

A Diary in the Age of Water explores the socio-political consequences of corruption in Canada, now owned by China and America as an indentured resource ‘reservoir’; it is a story told through four generations of women and their unique relationship with water during a time of great unheralded change. Centuries from now, in a dying boreal forest in what used to be northern Canada, Kyo, a young acolyte called to service in the Exodus, yearns for Earth’s past—the Age of Water—before the “Water Twins” destroyed humanity. Looking for answers and plagued by vivid dreams of this holocaust, Kyo discovers the diary of Lynna, a limnologist from that time of severe water scarcity just prior to the destruction. In her work for a global giant that controls Earth’s water, Lynna witnesses and records in her diary the disturbing events that will soon lead to humanity’s demise.

.

Waste Tide is an eco-techno thriller with compelling light-giving characters who navigate the dark bleak world of profiteers and greedy investors. Mimi is a migrant worker off the coast of China who scavenges through piles of hazardous technical garbage to make a living. She struggles, like the environment, in a larger power struggle for profit and power; but she finds a way to change the game, inspiring others. The story of Mimi and Kaizong—who she inspires—stayed with me long after I put the book down.

.

Fauna is at once beautiful and terrifying. Vadnais’s liquid prose immersed me instantly in her flowing story about change in this Darwinian eco-horror ode to climate change. I felt connected to the biologist Laura as she navigated through a torrent of rising mists and coiling snakes and her own transforming body with the changing world around her. It was an emotional rollercoaster ride that made me think.

.

The Word for World is Forest chronicles the struggles of the indigenous people under the conquering settlers through empathetic characters. The irony of what the indigenous peoples must do to save themselves runs subtle but tragic throughout the narrative. Given its relevance to our own colonial history and present situation, this simple tale rang through me like a tolling bell.

.

The Breathing Hole story begins in 1535, when the Inuk widow Hummiktuq risks her life to save a lost one-eared polar bear cub on an ice floe and adopts him. She names him Angu’ruaq. We soon learn that Angu’ruaq is timeless when we encounter him in scenes over the centuries from the Franklin Expedition in 1845 (who he helps by bringing them food) to 2031 when Angu’ruaq—old, hungry, his fur yellowing—returns to the breathing hole where long-dead Hummiktuq rescued him. By then the glaciers have receded and the ground is slush. Murphy’s spare and focused narrative achieves a timeless, dreamlike quality that plays strongly on the emotional connections of the reader; it elicits immense empathy for the Other in a deeply moving saga on the tragic dance of colonialism and climate change.

.

The Bear by Andrew Krivak is a fable of a post-anthropocene Earth told through the point of view of a young girl—possibly the only remaining human in the world—and the bear that guides her. Unlike the polar bear of The Breathing Hole, who remains silent and is clearly victimized by humanity’s actions, the black bear of The Bear lives with agency in a post-anthropocene world; he proselytizes and tells stories to instruct the girl on living harmoniously with Nature. His actions and elegant use of speech reflect his archetype as mentor in this story. This is foreshadowed in the fairytale the girl’s father recounts to her of a bear that saved a village from a cruel despot through cleverness and a sense of community.

.

Dune uses powerful world building and symbols of desert, water and spice coupled to the indigenous Fremen, to address exploitation and oppression by colonial greed.

The novel chronicles the journeys of new colonists and indigenous peoples of the desert planet Arrakis, enslaved by its previous colonists. The planet known as Dune lies at the heart of an epic story about taking, giving and sharing. The planet also serves as symbol to any new area colonized by settlers and already inhabited by Othered indigenous. It is the Mars of Martian Chronicles, the Bangkok of The Windup Girl, the North America of Barkskins.

.

Camp Zero, set in the remote Canadian north, is a feminist climate fiction that explores a warming climate through the perilous journeys of several female characters, each relating to her environment in different ways. Each woman exerts agency in surprising ways that include love, bravery and shared community. The strength of female power carried me through the pages like a braided river heading to a singular ocean. These very different women journey through the dark ruins of violent capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy—flowing past and through hubristic men pushing north with agendas and jingoistic visions—to triumph in an ocean of solidarity. I empathized with each woman as she found her strength and learned to wield true heroism—one based on collaboration and humble honesty.

.

We, written in 1920, is a hopeful dystopic work of courageous and unprecedented feminism. While the story centres on logical D-503, a man vacuously content as a number in the One State, it is I-330—Zamyatin’s unruly heroine—who stole my attention. Confident, powerful and heroic, the liberated I-330 embraces the Green Wind of change to influence D-503. A force of hope and resilience, she braves torture to successfully orchestrate a revolution that breaches the Green Wall—feats typically relegated to a male protagonist in novels of that era. When pregnant O-90 refuses to surrender her child to the State, I-330 helps her escape to the outside, where the Green Wind of freedom blows. I resonated with Zamyatin’s cautionary tale on the folly of logic without love and Nature.

.

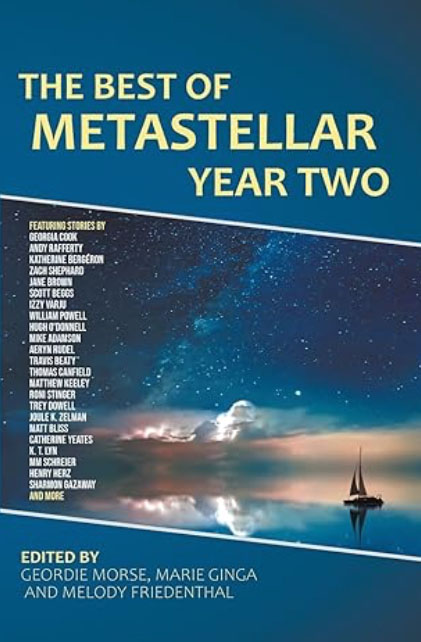

In Through the Portal: Tales from a Hopeful Dystopia, award-winning authors of speculative fiction Lynn Hutchinson Lee and Nina Munteanu present a collection that explores strange new terrains and startling social constructs, quiet morphing landscapes, dark and terrifying warnings, lush newly-told folk and fairy tales.

.

I list other significant and impactful eco-fiction books below:

- New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson

- Canadian Tales of Climate Change (edited) by Bruce Meyer

- Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

- Borne by Jeff Vandermeer

- Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad

- Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich

- Lost Arc Dreaming by Suyi Davies Okungbowa

- Greenwood by Micheal Christie

- Where the Crawdads Sing by Della Owens

- Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.