Jungfrau, Switzerland (photo by Nina Munteanu)

The writer’s journey from the passion and vulnerability of innocence to the wisdom of experience can be a dark and twisted road. In fact, if you are a writer of any merit, I guarantee you that yours will be too. Think Dante in the forest…

Yellow Creek, Ontario (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Let me tell you a story … It starts in the early 1990s. I was an eager young sprite entering the novel publishing world with my newly finished science fiction novel: “Escape from Utopia”. I’d published a few short stories and many articles by then. In addition, I’d published many scientific papers and reports. Confident and cocky, I was proud of my novel and eager to share it with the world. And I thought I knew my way through that dark forest…

I zealously sent the manuscript to a bazillion agents and editors. I was rewarded for my zealous efforts with a tidal wave of rejection letters. Mostly form letters (see my amusing account of the evolution of rejection letters in my fiction writing guidebook, The Fiction Writer) and an excerpt in a previous post here: “Rejection, Part 2: the Evolution of Rejection”

Then it came: an enthusiastic letter from an agent (I can’t remember the name: Literary Bridge or something); they said my work had great promise and that with some help from an editing firm they would consider representing me if I had it edited and resubmitted.

They recommended Edit Ink.

Those of you in the know and with some history in the industry may recall the Edit Ink scandal of the 90s. In short, it was a bait-and-switch scam that Bill Appel and Denise Sterrs (of Edit Ink) and their associated literary agents ran for close to a decade. Edit Ink was a “book doctor” firm near Buffalo, New York. The State of New York eventually convicted Appel and Sterrs and associates for defrauding prospective writers of several million dollars.

I remember my heart swelling with gratitude and optimism. Finally, someone liked my book! I naively considered their recommendation. Soon after—within days—I got an invitational letter from the pro-active Edit Ink. I can’t remember the exact content, except that they assured me that only the most promising writers were recommended to them by this particular agent. I remember seriously considering their offer. Then I got two more letters, one from another agent who recommended Edit Ink and another invitational letter from Edit Ink. Alarm bells went off. I went from naively hopeful to cynically suspicious. I did some investigating (something I should have done initially); by then the buzz was already on the Internet on their questionable practices. The lawsuit by New York State had yet to happen.

The Science Fiction Writers Association (SFWA) runs a “writer Beware” page, where memorable cases are reviewed. It’s worthwhile perusing just for your general knowledge and edification.

Here’s what they said about Edit Ink:

Founded by the husband and wife team of Bill Appel and Denise Sterrs, Edit Ink was a New York State-based editing service that engaged in a kickback referral scheme with a wide network of literary agents. Here’s how the scheme worked.

- Participating agents sent letters to writers who’d submitted manuscripts the agents didn’t want to represent, saying that the writer’s work showed “promise” but “wasn’t quite ready for publication.” A useful service was recommended: Edit Ink, which for a fee would polish the ms. to make it more salable. Once the ms. had been edited, the agent would then be glad to reconsider it.

- The agent forwarded the writer’s name to Edit Ink, which sent off a solicitation letter claiming, among other things, that Edit Ink received referrals for only a “select few” manuscripts (false), and that most publishing houses insisted on receiving “professionally edited” work (falser).

- If the writer took the bait and paid for an edit, the referring agent received a kickback of 15%.

- Writers who resubmitted their edited manuscripts to referring agents, per the referring agents’ suggestions, were given the brushoff. Either the market had “changed in the interim”, or the agency was “no longer representing that genre.”

Edit Ink charged $5 per page–exorbitant at the time even for a qualified editorial service, which Edit Ink very definitely was not. Its staff mostly consisted of recent college graduates with no publishing experience, working long hours for minimum wage. The typical Edit Ink edit was slipshod and superficial, consisting mainly of basic copy editing suggestions, and omitting the kind of in-depth analysis of plot, theme, character, and structure that might make a professional edit worthwhile.

At its height, dozens of literary agencies participated in the scheme. Edit Ink even set up its own bogus agencies and publishers to funnel more manuscripts its way. It’s estimated that the company made in excess of $5 million.

Mounting complaints from writers, and efforts by writers’ advocacy groups, at last spurred New York State to take action. In January 1998 the NYS Attorney General announced a lawsuit against Edit Ink for deceptive business practices, false advertising, and fraud.

Throughout the appeals process, Edit Ink continued to operate. Many questionable agents continued to refer manuscripts, and Aardvark Literary Agents (one of Edit Ink’s original bogus agencies) was taken over by co-defendant Kelley Culmer so it could go on functioning as a conduit for Edit Ink referrals. Business was dwindling, however–in part as a result of media attention, but largely because of spreading word in the then relatively new environment of the Internet. Once the appeal was denied, the thrill was gone. In August 1999, Appel and Sterrs closed Edit Ink’s doors for good.

Shades of Edit Ink

Edit Ink is by no means unique in the publishing industry. “Book doctors”, associated kick-back agents and subsidy publishers are, in fact, on the rise. This is not surprising, in view of the current rise in self-publishing and associated models. The industry is currently inundated with a range of publishing models from straight printing-only firms to full service publishing houses and anything in-between.

Author Victoria Strauss on her blog “Writer Beware” shares this story:

Over the past couple of days, I’ve heard from several writers who queried agents at Objective Entertainment, a relatively new literary agency with a strong track record and experienced staff, and received the following response:

Dear [name retracted],

Thank you so much for contacting us at Objective Entertainment. We have reviewed your material and we would like to refer you to one of our Publishers who we trust and believe will be able to serve you best. In order to do this I need your permission and the following information so they can either contact you via Phone or Email. The following information we need is if you would like to receive their newsletter and special offers. I think this is an amazing opportunity for you.

Please reply with the information we asked so that we can get you that one step closer to getting your work published!

Best

Tracey Ravenelle

Objective Entertainment

When the writers, eager to know the name of the publisher, requested more information, they received this response from Ms. Ravenelle:

We work with Iuniverse and AuthorHouse. Iuniverse has the number 5 book this week on the NY Times Best Seller List!

The writers then asked why Objective was recommending a self-publishing service. As of this writing, only one has received a response, which Ms. Strauss reproduced below exactly as it was sent to her:

Because we believe they would be the most beneficial for you at this point in time. Then you would come back to us after the sales starting racking up and we go major! This is the best way for an author to get their work out their. One of their books is number 5 on this weeks upcoming NY Times Best Seller list. So we believe they can help our potential future clients immensely.

EEK… aside from their atrocious grammar, Objective made some questionable recommendations. The major one being that of referring rejected clients to a self-publishing service (of course, they got a fee for referring clients to the house).

Vanity and Subsidy Publishers

SFWA shares another story:

Thousands of writers worldwide entered into contracts with Commonwealth Publications of Canada, a vanity publisher founded in 1995 by fee-charging literary agent Donald Phelan. Phelan worked with a number of other fee-charging agents who, in exchange for a kickback, recommended Commonwealth’s vanity contracts to their clients. Phelan also advertised for manuscripts in magazines such as Writer’s Digest and Writer’s Journal. (Writers take note: this is just one example of why you shouldn’t trust the classified ads in writers’ magazines.)

Commonwealth, which identified itself as a “subsidy” publisher (the implication being that the writer was contributing only a portion of the cost) typically charged $4,500 for publication, with a promised print run of 10,000. Its glossy promotional material promised all kinds of support to its authors: editing, proofreading, marketing, international distribution. But few of these services were actually delivered–and there were many other problems. Publication dates were delayed. Authors didn’t receive the number of books they were promised. The quality of finished books was poor. Books never showed up in bookstores. Royalties from books supposedly sold were never paid.

Fee-Charging Agents

SWFA shares this recent story:

On January 7, 2010, UK literary agent/film producer Robin Price appeared in court, accused of stealing more than half a million pounds from clients.

Price is alleged to have encouraged authors to pay exaggerated literary fees and invest in non-existent film deals, and has been charged with six counts of theft, most committed over the course of several years.

Even successful established writers were taken in by this one.

Writer Brian Knight, who suffered a book doctor agent scam, shares this advice: “New writers need to know that these people are still out there, spewing false promises … patting us on the back with one hand and picking our pockets with the other.” He advises new writers to research every individual and business with which they intend to do business.

Reign in your excitement and enthusiasm. Breathe. Then do the research. “Google.com is your friend,” says Knight. “There are other online resources available to writers. In this era of the information super-highway, it has never been easier to arm yourself against the scumbags and swindlers who make their living off the trusting and naive.” Knight also suggests, www.duotrope.com.

A great site to check out anyone in the writing and publishing industry is “Preditors and Editors” (intentionally misspelled). A site I have come to rely on for excellent market advice is www.ralan.com.

The writer’s journey is a hero’s journey, fraught with obstacles, dangerous distractions, and great disappointments (see Christopher Vogel’s excellent book The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers for more). But it is a path illuminated by a beacon of passionate expression, great sharing and exquisite victory. Choose your hero archetype carefully: choose magician.

We are the shamans, the myth-makers of our community and society. The artist / writer carries her archetypal message through story to her tribe, her community, her society and her world. It is both fulfilling and a great responsibility.

After the Edit Ink debacle, I picked myself up—a little wiser and a little more careful—and went on to find a traditional publishing house who published my first and second novels. Escape from Utopia became Angel of Chaos published by Dragon Moon Press (Part 1 of the Darwin’s Paradox duology), and I went on to publish seven more novels through traditional, indie, and self-publishing models: a historical fantasy, an SF adventure trilogy, two romantic SF novels, a short story collection (Natural Selection) and two text books on writing.

I haven’t looked back since… except to write this article, that is.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Run Your Novel and Short Story Submissions Like a Bus Depot

Run Your Novel and Short Story Submissions Like a Bus Depot Munteanu, Nina. 2013. “Virtually Yours” in

Munteanu, Nina. 2013. “Virtually Yours” in

The knight standing in the mire is Vivianne.

The knight standing in the mire is Vivianne.

The Splintered Universe Trilogy by Nina Munteanu (Starfire). 2011-2014. This trilogy, starting with Outer Diverse, follows the quest of Galactic Guardian Rhea Hawke, a wounded hero who must solve the massacre of a spiritual sect that takes her on her own metaphoric journey of self-discovery to realize power in compassion and forgiveness.

The Splintered Universe Trilogy by Nina Munteanu (Starfire). 2011-2014. This trilogy, starting with Outer Diverse, follows the quest of Galactic Guardian Rhea Hawke, a wounded hero who must solve the massacre of a spiritual sect that takes her on her own metaphoric journey of self-discovery to realize power in compassion and forgiveness. Darwin’s Paradox by Nina Munteanu (Dragon Moon Press). 2007. An eco-thriller about a woman unjustly exiled for murder and her quest for justice in a world ruled by technology and scientists.

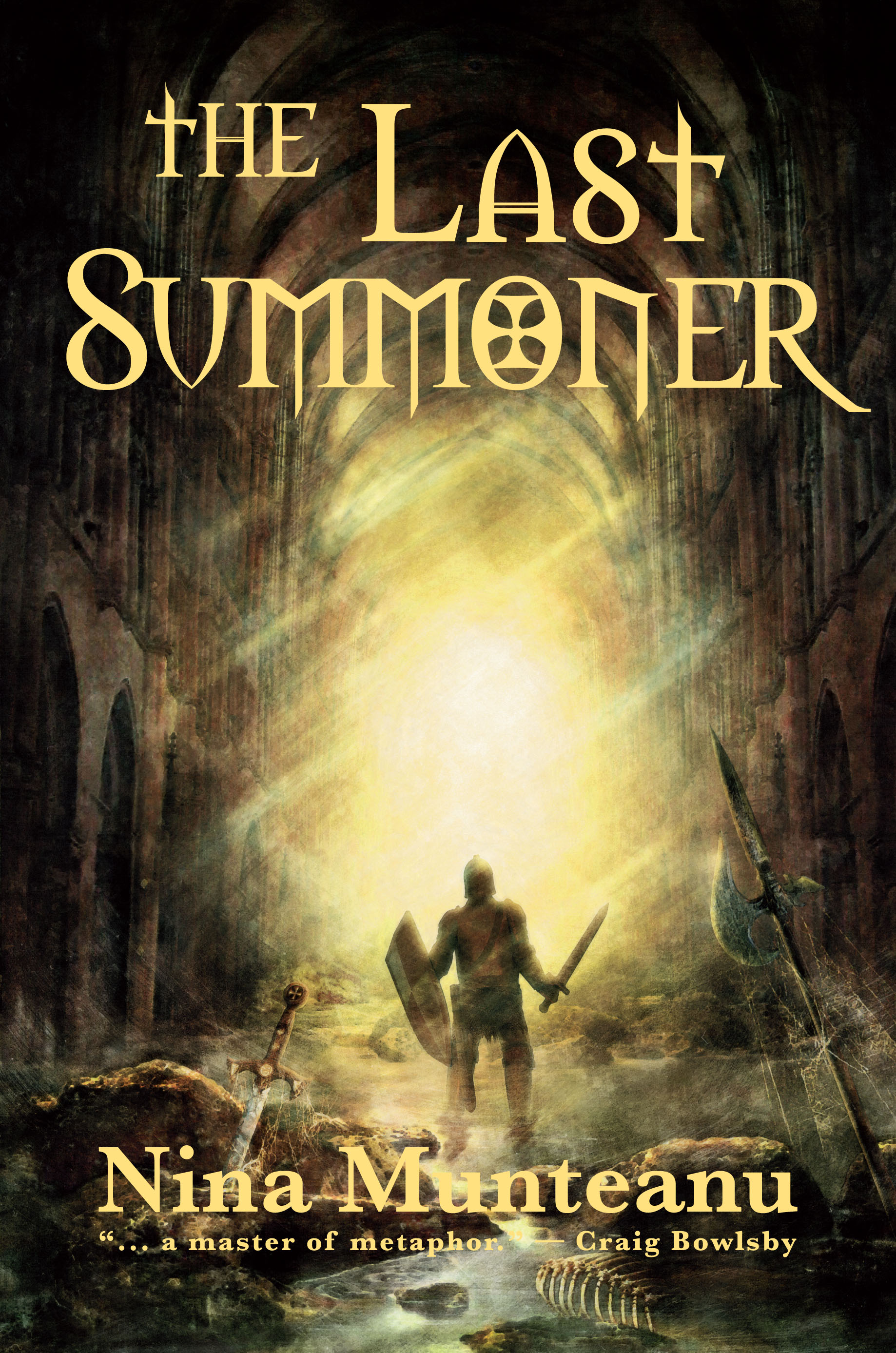

Darwin’s Paradox by Nina Munteanu (Dragon Moon Press). 2007. An eco-thriller about a woman unjustly exiled for murder and her quest for justice in a world ruled by technology and scientists. The Last Summoner by Nina Munteanu (Starfire). 2012. A young baroness discovers that her strange powers enable her to change history … but at a cost. Vivianne begins her journey in the year 1410, on the eve of a great battle. She dreams of her Ritter (knight), who will save her from her ill-fated marriage and the strange events that follow. But early on, she realizes that she is the Ritter she keeps dreaming about. She must save herself and her world.

The Last Summoner by Nina Munteanu (Starfire). 2012. A young baroness discovers that her strange powers enable her to change history … but at a cost. Vivianne begins her journey in the year 1410, on the eve of a great battle. She dreams of her Ritter (knight), who will save her from her ill-fated marriage and the strange events that follow. But early on, she realizes that she is the Ritter she keeps dreaming about. She must save herself and her world.

Père showed Vivianne how the height of the written area should equal the width of the whole page in a well-proportioned manuscript. Père also showed her how to rule the guidelines for the script and make the initial under-drawing of her illumination in plummet then in ink after which the gold leaf was applied. Vivianne had become adept at applying the gold leaf over the raised gesso, that she made of slaked lime and white lead mixed with pink clay, sugar, a dash of gum and egg glair glue. After painstakingly painting the gesso where she wanted the gold leaf to remain and letting it dry, Vivianne then carefully lowered the fragile tissue-thin leaf over the gesso and pressed down through a piece of silk then buffed the gold to a brilliant finish with a dog’s tooth by vigorously rubbing back and forth until it was smooth and the edges where there was no gessocrumbled away.

Père showed Vivianne how the height of the written area should equal the width of the whole page in a well-proportioned manuscript. Père also showed her how to rule the guidelines for the script and make the initial under-drawing of her illumination in plummet then in ink after which the gold leaf was applied. Vivianne had become adept at applying the gold leaf over the raised gesso, that she made of slaked lime and white lead mixed with pink clay, sugar, a dash of gum and egg glair glue. After painstakingly painting the gesso where she wanted the gold leaf to remain and letting it dry, Vivianne then carefully lowered the fragile tissue-thin leaf over the gesso and pressed down through a piece of silk then buffed the gold to a brilliant finish with a dog’s tooth by vigorously rubbing back and forth until it was smooth and the edges where there was no gessocrumbled away.