“Water Is…” leads Atwood’s Pick for Books of 2016

Every year, near Christmas, The New York Times puts out “The Year in Reading” in which they ask notably avid readers—who also happen to be poets, musicians, diplomats, filmmakers, novelists, actors and artists—to share the books that accompanied them through that year.

Every year, near Christmas, The New York Times puts out “The Year in Reading” in which they ask notably avid readers—who also happen to be poets, musicians, diplomats, filmmakers, novelists, actors and artists—to share the books that accompanied them through that year.

For the 2016 Year In Reading, The Times asked a prestigious and diverse readership, including Junot Diaz, Paul Simon, Carl Bernstein, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Elizabeth Banks, Samantha Power, Philip Pullman, Ann Pratchett, Orhan Pamuk, Drew Gilpin Fause, Anne Tyler, and many others to share their books of 2016.

There was also Booker Prize-winning and celebrated Canadian author and poet Margaret Atwood.

Margaret Atwood is a winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature as well as the Booker Prize (several times) and the Governor General’s Award. Animals and the environment feature in many of her books, particularly her speculative fiction, which reflects a strong view on environmental issues.

Margaret Atwood is a winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature as well as the Booker Prize (several times) and the Governor General’s Award. Animals and the environment feature in many of her books, particularly her speculative fiction, which reflects a strong view on environmental issues.

Several of her latest works (e.g., Oryx and Crake, Year of the Flood, MaddAddam) are eco-fiction and may be considered climate fiction. Atwood and partner, novelist Graeme Gibson, are the joint honorary presidents of the Rare Bird Club within BirdLife International. Atwood’s highly popular graphic novel Angel Catbird reflects an environmental sensitivity to the balance between wildlife and humans and their pets in urban settings.

Atwood’s choice for 2016 books came from her active, astute and compassionate environmentalism. Suggesting that many of her ‘The Year in Reading’ co-readers would emphasize fiction, history and politics, Atwood chose her books “instead from a still-neglected sector. All hail, elemental spirits! You’re making a comeback!”

Here are the four books Atwood recommends and why:

“Water Is…: The Meaning of Water” (Pixl Press) by Nina Munteanu. “We can’t live without it, so maybe we should start respecting it,” says Atwood. “This beautifully designed book by a limnologist looks at water from 12 different angles, from life and motion and vibration to beauty and prayer.” Water is emerging as one of the single most important resources of Planet Earth. Already scarce in some areas, it has become the new “gold” to be bought, traded, coveted, cherished, hoarded, and abused worldwide. It is currently traded on the Stock Exchange…Some see water as a commodity like everything else that can make them rich; they will claim it as their own to sell. Yet it cannot be “owned” or kept. Ultimately, water will do its job to energize you and give you life then quietly take its leave; it will move mountains particle by particle with a subtle hand; it will paint the world with beauty then return to its fold and rejoice; it will travel through the universe and transform worlds; it will transcend time and space to share and teach.

“Water Is…: The Meaning of Water” (Pixl Press) by Nina Munteanu. “We can’t live without it, so maybe we should start respecting it,” says Atwood. “This beautifully designed book by a limnologist looks at water from 12 different angles, from life and motion and vibration to beauty and prayer.” Water is emerging as one of the single most important resources of Planet Earth. Already scarce in some areas, it has become the new “gold” to be bought, traded, coveted, cherished, hoarded, and abused worldwide. It is currently traded on the Stock Exchange…Some see water as a commodity like everything else that can make them rich; they will claim it as their own to sell. Yet it cannot be “owned” or kept. Ultimately, water will do its job to energize you and give you life then quietly take its leave; it will move mountains particle by particle with a subtle hand; it will paint the world with beauty then return to its fold and rejoice; it will travel through the universe and transform worlds; it will transcend time and space to share and teach.

“The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World” (Greystone Books) by Peter Wohlleben. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben shares his deep love of woods and forests and explains the amazing processes of life, death, and regeneration he has observed in the woodland and the amazing scientific processes behind the wonders of which we are blissfully unaware. Much like human families, tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, and support them as they grow, sharing nutrients with those who are sick or struggling and creating an ecosystem that mitigates the impact of extremes of heat and cold for the whole group. As a result of such interactions, trees in a family or community are protected and can live to be very old. In contrast, solitary trees, like street kids, have a tough time of it and in most cases die much earlier than those in a group. Drawing on groundbreaking new discoveries, Wohlleben presents the science behind the secret and previously unknown life of trees and their communication abilities; he describes how these discoveries have informed his own practices in the forest around him. As he says, a happy forest is a healthy forest, and he believes that eco-friendly practices not only are economically sustainable but also benefit the health of our planet and the mental and physical health of all who live on Earth.

“The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World” (Greystone Books) by Peter Wohlleben. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben shares his deep love of woods and forests and explains the amazing processes of life, death, and regeneration he has observed in the woodland and the amazing scientific processes behind the wonders of which we are blissfully unaware. Much like human families, tree parents live together with their children, communicate with them, and support them as they grow, sharing nutrients with those who are sick or struggling and creating an ecosystem that mitigates the impact of extremes of heat and cold for the whole group. As a result of such interactions, trees in a family or community are protected and can live to be very old. In contrast, solitary trees, like street kids, have a tough time of it and in most cases die much earlier than those in a group. Drawing on groundbreaking new discoveries, Wohlleben presents the science behind the secret and previously unknown life of trees and their communication abilities; he describes how these discoveries have informed his own practices in the forest around him. As he says, a happy forest is a healthy forest, and he believes that eco-friendly practices not only are economically sustainable but also benefit the health of our planet and the mental and physical health of all who live on Earth.

“Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants” (Ecco) by Richard Mabey. “They’re better for you than you think,” says Atwood. “They hold the waste spaces of the world in place, and you can eat some of them.” Ever since the first human settlements 10,000 years ago, weeds have dogged our footsteps. They are there as the punishment of ‘thorns and thistles’ in Genesis and , two millennia later, as a symbol of Flanders Field. They are civilisations’ familiars, invading farmland and building-sites, war-zones and flower-beds across the globe. Yet living so intimately with us, they have been a blessing too. Weeds were the first crops, the first medicines. Burdock was the inspiration for Velcro. Cow parsley has become the fashionable adornment of Spring weddings. Weaving together the insights of botanists, gardeners, artists and poets with his own life-long fascination, Richard Mabey examines how we have tried to define them, explain their persistence, and draw moral lessons from them. One persons weed is another’s wild beauty.

“Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants” (Ecco) by Richard Mabey. “They’re better for you than you think,” says Atwood. “They hold the waste spaces of the world in place, and you can eat some of them.” Ever since the first human settlements 10,000 years ago, weeds have dogged our footsteps. They are there as the punishment of ‘thorns and thistles’ in Genesis and , two millennia later, as a symbol of Flanders Field. They are civilisations’ familiars, invading farmland and building-sites, war-zones and flower-beds across the globe. Yet living so intimately with us, they have been a blessing too. Weeds were the first crops, the first medicines. Burdock was the inspiration for Velcro. Cow parsley has become the fashionable adornment of Spring weddings. Weaving together the insights of botanists, gardeners, artists and poets with his own life-long fascination, Richard Mabey examines how we have tried to define them, explain their persistence, and draw moral lessons from them. One persons weed is another’s wild beauty.

“Birds and People” (Jonathan Cape) by Mark Cocker. “Vast, historical, contemporary, many-levelled,” says Atwood. “We’ve been inseparable from birds for millenniums. They’re crucial to our imaginative life and our human heritage, and part of our economic realities.” Vast in both scope and scale, the book draws upon Mark Cocker’s forty years of observing and thinking about birds. Part natural history and part cultural study, it describes and maps the entire spectrum of our engagements with birds, drawing in themes of history, literature, art, cuisine, language, lore, politics and the environment. In the end, this is a book as much about us as it is about birds.

“Birds and People” (Jonathan Cape) by Mark Cocker. “Vast, historical, contemporary, many-levelled,” says Atwood. “We’ve been inseparable from birds for millenniums. They’re crucial to our imaginative life and our human heritage, and part of our economic realities.” Vast in both scope and scale, the book draws upon Mark Cocker’s forty years of observing and thinking about birds. Part natural history and part cultural study, it describes and maps the entire spectrum of our engagements with birds, drawing in themes of history, literature, art, cuisine, language, lore, politics and the environment. In the end, this is a book as much about us as it is about birds.

“Time to pay attention to the nonhuman life around us, without which human life would fail,” Atwood concludes.

As we enter a new year of great uncertainty, particularly on how we and our environment will fare in a shifting political wind, these books offer diverse insight, a fresh and needed perspective and critical connection with our natural world–and each other through it.

Buy them, discuss them, share them. And save this planet.

Happy New Year!

Jungfrau, Switzerland (photo by Nina Munteanu)

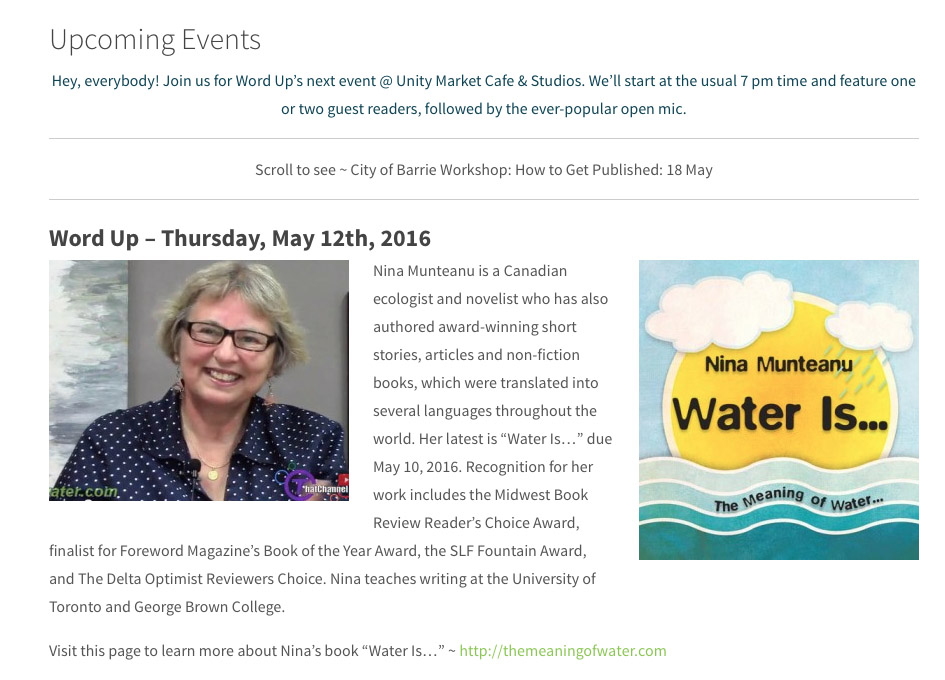

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction.

At Calgary’s When Words Collide this past August, I moderated a panel on Eco-Fiction with publisher/writer Hayden Trenholm, and writers Michael J. Martineck, Sarah Kades, and Susan Forest. The panel was well attended; panelists and audience discussed and argued what eco-fiction was, its role in literature and storytelling generally, and even some of the risks of identifying a work as eco-fiction. I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it.

I submit that if we are noticing it more, we are also writing it more. Artists are cultural leaders and reporters, after all. My own experience in the science fiction classes I teach at UofT and George Brown College, is that I have noted a trend of increasing “eco-fiction” in the works in progress that students are bringing in to workshop in class. Students were not aware that they were writing eco-fiction, but they were indeed writing it. Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility).

Just as Bong Joon-Ho’s 2014 science fiction movie Snowpiercer wasn’t so much about climate change as it was about exploring class struggle, the capitalist decadence of entitlement, disrespect and prejudice through the premise of climate catastrophe. Though, one could argue that these form a closed loop of cause and effect (and responsibility). The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

The self-contained closed ecosystem of the Snowpiercer train is maintained by an ordered social system, imposed by a stony militia. Those at the front of the train enjoy privileges and luxurious living conditions, though most drown in a debauched drug stupor; those at the back live on next to nothing and must resort to savage means to survive. Revolution brews from the back, lead by Curtis Everett (Chris Evans), a man whose two intact arms suggest he hasn’t done his part to serve the community yet.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

In my latest book Water Is… I define an ecotone as the transition zone between two overlapping systems. It is essentially where two communities exchange information and integrate. Ecotones typically support varied and rich communities, representing a boiling pot of two colliding worlds. An estuary—where fresh water meets salt water. The edge of a forest with a meadow. The shoreline of a lake or pond.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit  A while ago I wrote about the importance of an effective—and accurately portrayed—

A while ago I wrote about the importance of an effective—and accurately portrayed—

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps.

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps. After the release of the print book, Future Fiction released “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) in ebook format. The ebook contains the “Way of Water” story and another story, “Virtually Yours” (“Virtualmente tua”) alongside “The Story of Water” (non-fiction), which can be purchased in either Italian or Engish versions.

After the release of the print book, Future Fiction released “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) in ebook format. The ebook contains the “Way of Water” story and another story, “Virtually Yours” (“Virtualmente tua”) alongside “The Story of Water” (non-fiction), which can be purchased in either Italian or Engish versions.

Ebook (Italian OR English) with additional short story “Virtually Yours” through Future Fiction (Mincione Edizioni) for €1,99 at:

Ebook (Italian OR English) with additional short story “Virtually Yours” through Future Fiction (Mincione Edizioni) for €1,99 at:

Some time ago, I was invited by writer and editor

Some time ago, I was invited by writer and editor

In her book The Art of Slow Writing, Louise DeSalvo tells the story of how Ian McEwan composed his book Atonement.

In her book The Art of Slow Writing, Louise DeSalvo tells the story of how Ian McEwan composed his book Atonement.

I originally wrote the Paris section in Vivianne’s point of view, but it seemed flat with too obvious fish-out-of-water observations. I let the book sit, while I conducted more research on Paris, and then it came to me: give the narrative to François. This part of the book was his story. By giving François the only POV, I also gave his character agency to react and change to Vivianne’s role as “catalyst hero.” I rewrote this section, starting with François fleeing from a street crime he’d committed, when Vivianne literally appears and knocks him down. She then sweeps him up in a high-stakes chase that will change his worldview. When Vivianne returns to 1410 Poland in the last section of the book, her great journey of self-discovery and atonement begins.

I originally wrote the Paris section in Vivianne’s point of view, but it seemed flat with too obvious fish-out-of-water observations. I let the book sit, while I conducted more research on Paris, and then it came to me: give the narrative to François. This part of the book was his story. By giving François the only POV, I also gave his character agency to react and change to Vivianne’s role as “catalyst hero.” I rewrote this section, starting with François fleeing from a street crime he’d committed, when Vivianne literally appears and knocks him down. She then sweeps him up in a high-stakes chase that will change his worldview. When Vivianne returns to 1410 Poland in the last section of the book, her great journey of self-discovery and atonement begins. 2012 and remained a Canadian bestseller on Amazon for several months. It represents my first historical fantasy in an otherwise repertoire of hard science fiction. The cover of the book is indeed the original image that had inspired the book in the first place; and was kindly acquired by my publisher. The Polish and Lithuanians celebrate June 14th with pride, erecting mock-ups of the battle annually. Some day I hope to participate.

2012 and remained a Canadian bestseller on Amazon for several months. It represents my first historical fantasy in an otherwise repertoire of hard science fiction. The cover of the book is indeed the original image that had inspired the book in the first place; and was kindly acquired by my publisher. The Polish and Lithuanians celebrate June 14th with pride, erecting mock-ups of the battle annually. Some day I hope to participate.