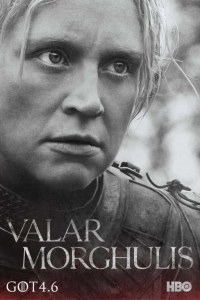

She’s called The Angel of Verdun. You also see another name scrawled in bright red over a London bus: Full Metal Bitch. When we first see her, angry and fierce in her battle gear (which resembles a modern-day knight’s armour) she’s heading out to battle, stomping out of the bunker, surrounded by an entourage, and summarily knocks an acolyte down who gets in her way. She’s badass. She’s the Full Metal Bitch.

Her real name is Rita Vrataski. She wields a sharpened helicopter blade as her weapon of choice and serves as the poster girl for the United Defense Force to recruit more into the fight.

Rita (Emily Blunt) is a very different kind of poster girl for the war effort of the recent SF action movie Edge of Tomorrow, directed by Doug Liman and written by Christopher McQuarrie. There is an “edge of tomorrow” in this military SF story that explores how much we’ve changed since the time of World War I and II. And that change is most apparent in how women are seen and act.

Edge of Tomorrow makes subtle and not so subtle reference to both world wars: from its June 6th release (70th anniversary of D-Day and the massive and decisive Normandy landing) to its reference to the trenches of Verdun in WWI, the Nazi or German Empire forces as the original seat of the Omega entity and many more.

The premise is straight-forward science fiction stuff: Earth is under attack by an alien species, who have seeded themselves with a meteor shower. The aliens have conquered Russia and China and now threaten France and England. Evoking echoes of World War II’s Normandy invasion, the United States joins the fray in support of their allies.

American Major William Cage (Tom Cruise), who is with the PR staff of the war effort, gets unwillingly drafted to the front as a rookie private and dies in the first five minutes of landing on the shores of Normandy—but not before he kills an alpha alien, which covers him in blue blood. This sends him into a vicious time loop, where he must relive and die over and over in that horrendous bloodbath. Each time, he glimpses the Angel of Verdun repeatedly killed. On one occasion, Vrataski runs across him, lying injured in the mud. He can’t move, sure victim to the aliens. She snatches his battery pack and moves on, leaving him there to die. Astonished at the Angel’s apparent lack of compassion, Cage will later mimic her “let him die” attitude when he knowingly lets fellow soldier Kimmel get crushed.

In a later iteration he finally meets Vrataski on the battlefield, where she realizes (having gone through the time loop and lost it) that he is now in a time loop and therefore the key to their victory; she tells him to find her when he wakes up just seconds before she lets herself get blown up and they begin their looping journey together.

To his complaint, “I’m not a soldier,” Vrataski replies, “No, you’re a weapon.” That’s how she sees him. And to that end, she mentors him in the art and science of soldiering. When things go awry she time and again unflinchingly shoots him dead to reset the time. Cage tries to engage her in casual conversation and finds her taciturn. “You don’t talk much,” he observes, to which she quips, “Not a fan.” She’s all about the business of defeating the enemy before the human race is wiped out.

Edge of Tomorrow provides a refreshing kind of woman hero; someone who is equal to her male protagonist in skill, intelligence and heroic stature. What I mean by heroic stature is that her heroic journey of transformation does not play subservient to her male counterpart’s journey. This almost happens on two occasions when Cage gives her an “out” to stay behind and let him take over. She declines. In fact, Cruise lets her character take the lead, even though this it truthfully Cage’s story of metaphoric transformation from “onlooker” to “participant”.

In so many androcentric storylines, the female—no matter how complex, interesting and tough she starts out being—must demure to the male lead; as if only by bowing down to his superior abilities can she help ensure his heroic stature. Returning us right back to the cliché role of the woman supporting the leading man to complete his hero’s journey. And this often means serving as the prize for his chivalry. We see this in so many action thrillers and action adventures today: Valka in How to Train Your Dragon, Wyldstyle in The Lego Movie, Neytiri in Avatar, Trinity in The Matrix, and so many more. There’s even a name for it: the Trinity Syndrome.

Tasha Robinson writes in her excellent article entitled, We’re losing all our Strong Female Characters to Trinity Syndrome: “The idea of the Strong Female Character—someone with her own identity, agenda, and story purpose—has thoroughly pervaded the conversation about what’s wrong with the way women are often perceived and portrayed today, in comics, video-games, and film especially…it’s still rare to see films in the mainstream action/horror/science-fiction/fantasy realm introduce women with any kind of meaningful strength, or women who go past a few simple stereotypes.”

I give Cruise, Liman and McQuarrie full credit for not doing this. For example, after Cage makes his case to his Squadron to go find the Omega in Paris, they remain reluctant until Vrataski emerges. “I don’t expect you to follow me,” says Cage. “I do expect you to follow her.” The Angel of Verdun—or better yet, the badass Full Metal Bitch. And why not? Who wouldn’t follow her?

Is this one of the reasons that this movie didn’t do so well in the North American box office as it did overseas, whose audience may reflect a more mature, open and enlightened audience?

When a female lead is stronger than the male protagonist, some reviewers (OK—male reviewers) treat and categorize that movie as a “woman’s story”. I’ve been told by some of my male friends that they couldn’t possibly empathize with such a character—mainly because she is a woman and she is stronger than the male lead “they want to be”. Invariably, in many of these, the male counterpart is so much “milk-toast” compared to that awesome female-warrior. And have you ever noticed that, while the male hero gets the girl, the female hero usually ends up alone? Great examples include: Buffy the Vampire Slayer; Xena: Warrior Princess; Sarah in The Terminator and of course Vasquez in Aliens. These women are amazons; they stand apart, goddess-like, unrelenting, unflinching—untouchable. It’s actually no wonder that my ex-husband dislikes Sigourney Weaver to this day—she could crush him underfoot and eat him for breakfast at a moment’s notice. And probably would!

In a superb article in NewStatesman entitled I hate Strong Female Characters, Sophia McDougall says:

“…I want to point out two things that Richard has, that Bond and Captain America and Batman also have, that Peggy (Carter of Captain America), however strong she is, cannot attain. They are very simple things, even more fundamental than “agency”.

- 1) Richard has the spotlight. However weak or distressed or passive he may be, he’s the main goddamn character.

- 2) Richard has huge range of other characters of his own gender around him, so that he never has to act as any kind of ambassador or representative for maleness. Even dethroned and imprisoned, he is free to be uniquely himself.

On the posters [women are] posed way in the back of the shot behind the men, in the trailers they may pout or smile or kick things, but they remain silent. Their strength lets them, briefly, dominate bystanders but never dominate the plot. It’s an anodyne, a sop, a Trojan Horse – it’s there to distract and confuse you, so you forget to ask for more.”

There is another type of female hero. She is equal to her male counterpart. Her story is not secondary to his story; her heroic status and hero’s journey is equal to his; in fact they may share the same journey. Examples include: The Expanse; Aeon Flux; Farscape; Battlestar Galactica, Hunger Games, The Beyond, Missions, Orphan Black, Advantageous…

And now Edge of Tomorrow. As with the above examples, Vrataski and Cage form a team, in which together they are more than the sum of their parts. A marriage of independent autopoiesis, combining skills, abilities and vision. This is also why, in my opinion, the ending of Edge of Tomorrow is totally appropriate: not because it’s “the happy ending”; but because it carries the message of enduring collaboration of equals.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Outer Diverse is the first book of the Splintered Universe Trilogy, set in and around the Milky Way Galaxy. The first book begins as Galactic Guardian Rhea Hawke intestigates the massacre of an entire religious sect, catapulting her into a treacherous storm of politics, conspiracy and self-discovery. Her quest for justice leads her into the heart of a universal struggle and toward an unbearable truth she’s hidden from herself since she murdered an innocent man.

Outer Diverse is the first book of the Splintered Universe Trilogy, set in and around the Milky Way Galaxy. The first book begins as Galactic Guardian Rhea Hawke intestigates the massacre of an entire religious sect, catapulting her into a treacherous storm of politics, conspiracy and self-discovery. Her quest for justice leads her into the heart of a universal struggle and toward an unbearable truth she’s hidden from herself since she murdered an innocent man.

In the androcratic model, a woman “hero” often presupposes she shed her feminine nurturing qualities of compassion, kindness, tenderness, and inclusion, to express those hero-defining qualities that are typically considered “male”. I have seen too many 2-dimensional female characters limited by their own stereotype in the science fiction genre—particularly in the adventure/thriller sub-genre. If they aren’t untouchable goddesses or “witches” in a gynocratic paradigm, they are often delegated to the role of enabling the “real hero” on his journey through their belief in him: as Trinity enables Neo; Hermione enables Harry; Mary Jane enables Spiderman; Lois enables Superman; etc. etc. etc.

In the androcratic model, a woman “hero” often presupposes she shed her feminine nurturing qualities of compassion, kindness, tenderness, and inclusion, to express those hero-defining qualities that are typically considered “male”. I have seen too many 2-dimensional female characters limited by their own stereotype in the science fiction genre—particularly in the adventure/thriller sub-genre. If they aren’t untouchable goddesses or “witches” in a gynocratic paradigm, they are often delegated to the role of enabling the “real hero” on his journey through their belief in him: as Trinity enables Neo; Hermione enables Harry; Mary Jane enables Spiderman; Lois enables Superman; etc. etc. etc.

liberator for Belters but is really a terrorist revolutionary group, looking to shift the balance of power); she naively joined to help the lowly belters achieve justice and a voice in the oppressive squeeze by Martian and Earth corporate interests. In “Back to the Butcher”, a colleague of Julie’s relates how she selflessly helped injured minors on Calisto in a tunnel collapse with cadmium poisoning: “I never saw her shed a tear over the fact that she’d have to take anti-cancer meds for the rest of her life.” The only time she cried, he shares, was when she was acknowledged as being a true “beltalowda.”

liberator for Belters but is really a terrorist revolutionary group, looking to shift the balance of power); she naively joined to help the lowly belters achieve justice and a voice in the oppressive squeeze by Martian and Earth corporate interests. In “Back to the Butcher”, a colleague of Julie’s relates how she selflessly helped injured minors on Calisto in a tunnel collapse with cadmium poisoning: “I never saw her shed a tear over the fact that she’d have to take anti-cancer meds for the rest of her life.” The only time she cried, he shares, was when she was acknowledged as being a true “beltalowda.”

from a higher calling, not from lust for power or self-serving greed. She’s seeks the truth. And, like Miller, she struggles with a conscience. Chrisjen is a complex and paradoxical character. Her passionate and unrelenting search for the truth together with unscrupulous methods, make her one of the most interesting characters in the growing intrigue of The Expanse. Avasarala is a powerful character on many levels—none the least in her potent presence (thanks to Shohreh Aghdashloo’s powerful performance); when Avasarala walks into a scene, all eyes turn to her.

from a higher calling, not from lust for power or self-serving greed. She’s seeks the truth. And, like Miller, she struggles with a conscience. Chrisjen is a complex and paradoxical character. Her passionate and unrelenting search for the truth together with unscrupulous methods, make her one of the most interesting characters in the growing intrigue of The Expanse. Avasarala is a powerful character on many levels—none the least in her potent presence (thanks to Shohreh Aghdashloo’s powerful performance); when Avasarala walks into a scene, all eyes turn to her.

operative and she finds herself ironically defending the Belt and Belters in the struggle between Earth and Mars. “We need to stick together,” she tells fellow Belter Miller and helps Fred Johnson’s team. Driven to help those in need, Naomi selflessly puts herself in harm’s way to save Belters used as lab rats on Eros or those left to die on Ganymede after a Mars and Earth skirmish. In an intimate moment with Holden after the atrocity on Eros with the proto-molecule experiment, Naomi reminds him: “We did not choose this but this is our fight now. We’re the only ones who know what’s going on down there; we’re the only ones with a chance to stop it.”

operative and she finds herself ironically defending the Belt and Belters in the struggle between Earth and Mars. “We need to stick together,” she tells fellow Belter Miller and helps Fred Johnson’s team. Driven to help those in need, Naomi selflessly puts herself in harm’s way to save Belters used as lab rats on Eros or those left to die on Ganymede after a Mars and Earth skirmish. In an intimate moment with Holden after the atrocity on Eros with the proto-molecule experiment, Naomi reminds him: “We did not choose this but this is our fight now. We’re the only ones who know what’s going on down there; we’re the only ones with a chance to stop it.”

Station. A complex character with mysterious connections and intuitive skills for people, Drummer gives one the impression that she can nimbly navigate between hard-line OPA and Fred’s Earther-version of OPA justice for Belters. In “Pyre”, she shows her mettle when—after being shot and held hostage by a militant faction on Tycho—she finds the strength to summarily execute them.

Station. A complex character with mysterious connections and intuitive skills for people, Drummer gives one the impression that she can nimbly navigate between hard-line OPA and Fred’s Earther-version of OPA justice for Belters. In “Pyre”, she shows her mettle when—after being shot and held hostage by a militant faction on Tycho—she finds the strength to summarily execute them.

Bobbie Draper (Frankie Adams) is a staunch hard-fighting Martian marine who dreams of a terraformed Mars with lakes and vegetation and breathable atmosphere. Because of Earth’s Vesta blockade, Draper realizes that she will not realize her childhood dream of seeing Mars “turned from a lifeless rock into a garden.” The blockade forced Mars to ramp up its military at the expense of terraforming. Draper laments that, “with all those resources moved to the military, none of us will live to see an atmosphere over Mars” and bears a strong resentment against Earth. However, when Bobbie discovers her own government’s culpability with an Earth weapons manufacturer that used her own marines as guinea pigs, she chooses honour over loyalty and defects to seek justice.

Bobbie Draper (Frankie Adams) is a staunch hard-fighting Martian marine who dreams of a terraformed Mars with lakes and vegetation and breathable atmosphere. Because of Earth’s Vesta blockade, Draper realizes that she will not realize her childhood dream of seeing Mars “turned from a lifeless rock into a garden.” The blockade forced Mars to ramp up its military at the expense of terraforming. Draper laments that, “with all those resources moved to the military, none of us will live to see an atmosphere over Mars” and bears a strong resentment against Earth. However, when Bobbie discovers her own government’s culpability with an Earth weapons manufacturer that used her own marines as guinea pigs, she chooses honour over loyalty and defects to seek justice.

The Secretary General (who she had a previous friendship that soured over some dubious event) has called Anna in to write a stirring speech to unite Earth behind the war erupting between Earth and Mars. Anna enters the political intrigue with naive hope and is badly used; but her inner strength, keen intelligence and courage propels her on an amazing trajectory of influence to the outer reaches of the solar system where first contact is imminent. Like a quiet summer rainstorm, Anna brings a fresh perspective on heroism through faith, hope and inclusion.

The Secretary General (who she had a previous friendship that soured over some dubious event) has called Anna in to write a stirring speech to unite Earth behind the war erupting between Earth and Mars. Anna enters the political intrigue with naive hope and is badly used; but her inner strength, keen intelligence and courage propels her on an amazing trajectory of influence to the outer reaches of the solar system where first contact is imminent. Like a quiet summer rainstorm, Anna brings a fresh perspective on heroism through faith, hope and inclusion.

to name just a few. The gender of the hero I empathized with was irrelevant. What remained important was their sensibilities and their actions of respect and integrity on behalf of humanity, all life and the planet.

to name just a few. The gender of the hero I empathized with was irrelevant. What remained important was their sensibilities and their actions of respect and integrity on behalf of humanity, all life and the planet.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and editor of the growing collection of works by Hal Friesen, Craig Bowlsby, Krysia Anderson, Elizabeth Woods, Nina Munteanu, Randy McCharles and others writing works set in the ORU. As a publisher, she is working with Kyle Davidson, Jeff Doten, Sarah Trick, Jennifer Lott, Paula Johanson, Lynn Perkins and Yukari Yamamoto in re-inventing publishing through Reality Skimming Press. Lynda holds three degrees and works as Learning Technology Analyst and manager of the Learn Tech support team at Simon Fraser University. She teaches part-time at BCIT.

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and editor of the growing collection of works by Hal Friesen, Craig Bowlsby, Krysia Anderson, Elizabeth Woods, Nina Munteanu, Randy McCharles and others writing works set in the ORU. As a publisher, she is working with Kyle Davidson, Jeff Doten, Sarah Trick, Jennifer Lott, Paula Johanson, Lynn Perkins and Yukari Yamamoto in re-inventing publishing through Reality Skimming Press. Lynda holds three degrees and works as Learning Technology Analyst and manager of the Learn Tech support team at Simon Fraser University. She teaches part-time at BCIT. Sarah Kades hung up her archaeology trowel and bid adieu to Traditional Knowledge facilitation to share her love of the natural world and happily-ever-afters. She writes literary romantic eco-fiction where nature, humour and love meet. She lives in Calgary, Canada with her family. Connect with Sarah on

Sarah Kades hung up her archaeology trowel and bid adieu to Traditional Knowledge facilitation to share her love of the natural world and happily-ever-afters. She writes literary romantic eco-fiction where nature, humour and love meet. She lives in Calgary, Canada with her family. Connect with Sarah on  Stephanie Johanson is the art director, assistant editor, and co-owner of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, publishing since 2003. She is an artist who has worked in a variety of media, though painting and soapstone carving are her passions. Stephanie paints realism with a hint of fantasy, often preferring landscapes as her subjects. Examples of her work can be viewed on the Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine website at

Stephanie Johanson is the art director, assistant editor, and co-owner of Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine, publishing since 2003. She is an artist who has worked in a variety of media, though painting and soapstone carving are her passions. Stephanie paints realism with a hint of fantasy, often preferring landscapes as her subjects. Examples of her work can be viewed on the Neo-opsis Science Fiction Magazine website at  Diane Walton is currently serving a life sentence as Managing Editor of On Spec Magazine, and loving every minute of it. She and her lovely and talented husband, Rick LeBlanc, share their rural Alberta home with three very entitled cats.

Diane Walton is currently serving a life sentence as Managing Editor of On Spec Magazine, and loving every minute of it. She and her lovely and talented husband, Rick LeBlanc, share their rural Alberta home with three very entitled cats.