In two excellent articles in Climate Cultures entitled “A History of Eco-fiction, Part 1 and 2”, eco-fiction author and critic Mary Woodbury starts out with several rather long definitions of eco-fiction—one provided by Jim Dwyer in his 2010 book Where the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to Eco-Fiction.

She also includes simpler descriptions. For instance, Ashland Creek Press calls it “fiction with a conscience,” and co-founder John Yunker insightfully labelled it a super-genre.

Woodbury then muses: “I think of eco-fiction as not so much a genre than as a way to intersect natural landscape, environmental issues, and wilderness—and human connection to these things—into any genre and make it come alive.” Not a fan of labels, she argues that eco-fiction is broad and has a rich history (of existence long before its label was coined in 1971 in the preface to an anthology by Washington Square Press) and brings up examples such as The Stolen Child by Victorian author and poet WB Yeats. “Eco-fiction has no boundaries in time or space,” argues Woodbury. “It can be set in the past, present, or future. It can be set in other worlds…I think of eco-fiction as a way to bring alive the wild in any genre, whether romance, adventure, mystery, you name it.”

Eco-fiction—like climate change—is a hyperobject. In his 2014 book Hyperobjects, Timothy Morton explains that hyperobjects are immense, non-local entities that challenge our traditional understanding of objects; things so massively distributed in time and space that they defy human perception, given they exist beyond our immediate sensory grasp yet affecting us profoundly. Examples include anthropogenic global warming / climate change, but also pervasive phenomena, like plastic and oil, that have far reaching impacts beyond their simple physical presence.

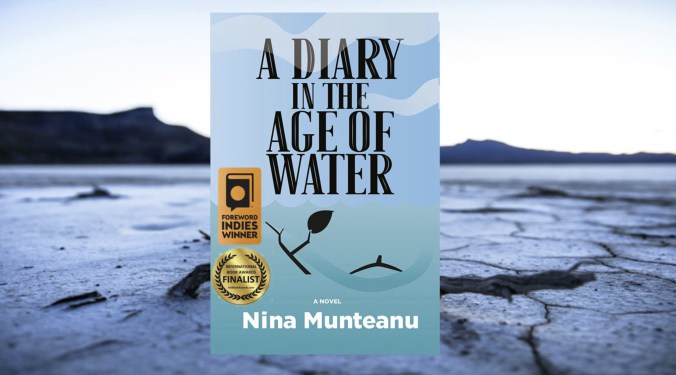

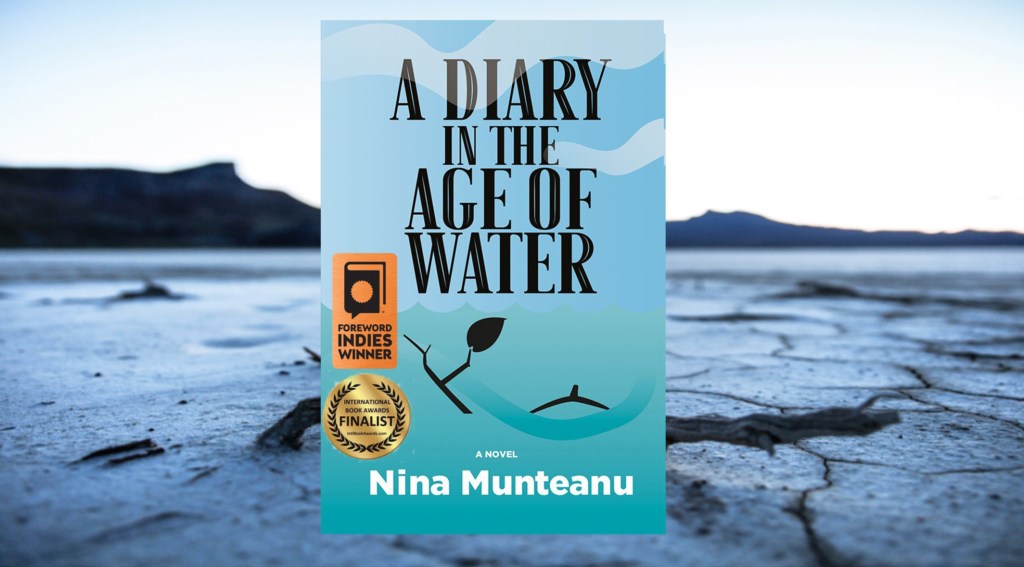

My own definition (from a previous article in Solarpunk Magazine) embraces the hyperobject nature of eco-fiction: eco-fiction (short for ecological fiction) is a kind of fiction in which the environment—or one aspect of the environment—plays a major role in story, either as premise or as character. For instance, several of my eco-fiction stories give Water a voice as character. In my latest novel, A Diary in the Age of Water, each of the four women characters reflects on her relationship with water and, in turn, her view of and journey in a changing world.

Through its vision of our future, eco-fiction encourages conversations and an outward perspective. Eco-fiction can trigger a sense of wonder about the natural world; it may connect with our sense of loss or mourning—our solastalgia—for our changing home. Cautionary tales may nudge people to action and encourage alternative futures. By encouraging empathy and imagination, eco-fiction reaches deep into our souls, where we care. It is only when we care that we act.

A recent survey conducted by Woodbury revealed that, “Fiction exploring humanity’s impacts on nature is becoming more popular [and] has the distinct ability to creatively engage and appeal to readers’ emotions.” Woodbury’s 2020 survey showed that “88% of its participants were inspired to act after reading ecological fiction.”

A few years ago, I wrote an article entitled “Why Ecofiction Will Save the World” which appeared in Issue #1 of Solarpunk Magazine. In it, I mentioned how I’d noticed in my university science fiction course that more and more students were bringing in WIPs on ecological and global environmental issues. Many of the stories involved a premise of environmental calamity, but not in the same vein as previous environmental disasters that depict “man” against Nature. Instead, these works gave the Earth or Nature (or an aspect of Nature) an actual voice—as a character—and had a protagonist who learns to interact with the Earth/Nature character, often cooperatively. This represents a palpable and gestalt cultural awakening of what eco-feminists have called the “feminine archetype” by providing a voice for “the other” in story.

.

This shift reflects what lies at the heart of eco-fiction.

Eco-fiction explores the world and the consequences of humanity’s actions on the environment and ourselves (by inference) through dramatization. The stories that stir our hearts come from deep inside, through symbols, archetypes and metaphor, where the personal meets the universal. In my short story “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”), water’s connection with love flows throughout the story:

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self-conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.

In a world of severe water scarcity through climate catastrophe and geopolitical oppression, the bond of these two girls—to each other through water and with water—is like the shifting covalent bond of a complex molecule, a bond that fuses a relationship of paradox linked to the paradoxical properties of water. Just as two water drops join, the two women find each other in the wasteland of environmental intrigue. Hilda’s relationship with Hanna—as with water—is both complex and shifting according to the bonds they make and break. Hilda navigates her dystopia by learning meaningful lessons—lessons that pertain directly to our reader in their current world. This is because the premise of a dystopia lies squarely in the present world. Good dystopias enlighten and suggest possibilities; they can warn and herald. At the very least, they incite the necessary conversation.

Our capacity—and need—to share stories is as old as our ancient beginnings. From the Paleolithic cave paintings of Lascaux to our blogs on the Internet, humanity has left a grand legacy of ‘story’ sharing. By providing context to knowledge, story moves us to care, to cherish, and, in turn, to act. What we cherish, we protect. It’s really that simple.

.

“Morton’s book is a queasily vertiginous quest to synthesize the still divergent fields of quantum theory (the weirdness of small objects) and relativity (the weirdness of big objects) and insert them into philosophy and art, which he notes are far behind ontologically speaking (page 150). Morton’s wager is that for the first time, we in the Anthropocene are able to see snapshots of hyperobjects, and that these intimations more or less will force us to undergo a radical reboot of our ontological toolkit and (finally) incorporate the weirdness of physics”—Cara Daggett

.

.

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning novelist and short story writer of eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy. She also has three writing guides out: The Fiction Writer; The Journal Writer; and The Ecology of Writing and teaches fiction writing and technical writing at university and online. Check the Publications page on this site for a summary of what she has out there. Nina teaches writing at the University of Toronto and has been coaching fiction and non-fiction authors for over 20 years. You can find Nina’s short podcasts on writing on YouTube. Check out this site for more author advice from how to write a synopsis to finding your muse and the art and science of writing.

.