I’ve just returned from Montreal, where I was invited to participate in a two-day conference hosted by McGill University’s Bieler School of Environment at Esplanade Tranquil. Named after Kim Stanley Robinson’s eco-fiction novel New York 2140, the conference brought together a diverse assemblage of scientists, academic researchers, urban planners, speculative fiction writers, artists, and students in a small setting dedicated to encourage cross-pollination of ideas and visions through panels and workshops. I sat on a panel and a roundtable with other writers, urban planners, engineers, scientists and activists to discuss futures through science and story. Much of the event focused on the literary genre called Hopepunk—a sub-genre of Speculative Fiction devoted to optimistic themes of scientific transformation, discovery and empathy. Resulting dialogue explored forms of communication, expression, and ways not just to deal with growing solastalgia, eco-grief, and environmental anxiety but to move forward through action and hope.

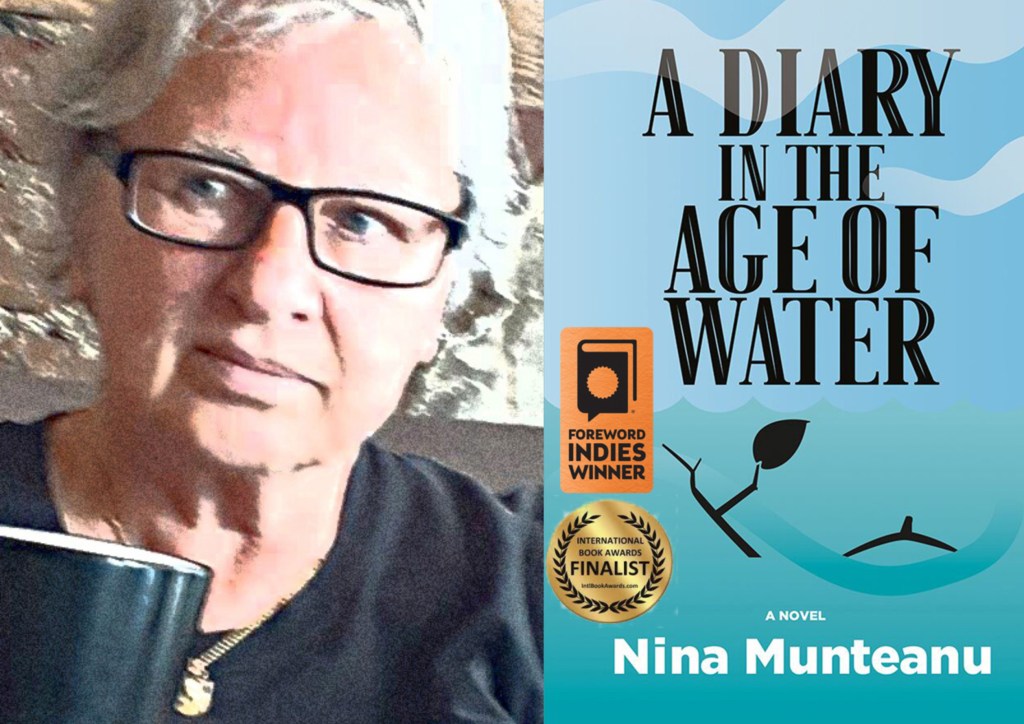

In the Thursday morning writer’s panel, in which we explored the role of science knowledge and hope in story, I shared the writing process I underwent with my latest published novel A Diary in the Age of Water, which I categorize as a hopeful dystopia (‘Hopeful dystopias’ are much more than an apparent oxymoron; they are in some fundamental way, the spearhead of the future—and ironically often a celebration of human spirit by shining a light through the darkness of disaster):

The main character in A Diary in the Age of Water was a limnologist like me who kept a journal (the diary referenced in the title of the book). This part of the story took place in the near-future when the water crisis and associated climate change phenomena had become calamitous. Being a scientist with so much intimate knowledge of the crisis, the diarist became cynical and lost her faith in humanity. I recall my own journey into despair as I did the research needed to convey the character’s knowledge and situation. I found myself creating a new character (the diarist’s daughter) much in the way a drowning swimmer takes hold of a life-saver, to pull me out of the darkness I’d tumbled into. The daughter’s hopeful nature and faith in humanity pulled both me and the reader out of the darkness. The cynical nature of the diarist came from a sense of being overwhelmed by the largeness of the crisis and froze her with feelings of powerlessness. The diarist’s daughter rose like an underground spring from the darkness by focusing on a single light: her friend and lover who pointed to a way forward. As Greta so aptly said once, “action leads to hope” and hope leads to action. Despite the dire circumstances in the novel, I think of A Diary in the Age of Water as a story of resilience. And ultimately of hope.

I came to the conference as a writer, scientist, mother, and environmental activist. What I discovered was an incredible solidarity with a group so diverse in culture, disciplines, expression and language—and yet so singularly united. It was heartwarming. Hopeful. And necessary. This conference ultimately felt like a lifeline to a world of possibilities.

Organizers brought in a wide variety of talent, skill, and interest and challenged everyone through well-run workshops to think, feel, discover, discuss, collaborate and express. Workshops, panels, and multimedia art incited co-participation with all attendees in imaginative and fun ways. On-site lunches and drinks helped keep everyone together and provided further space for interaction and discussion.

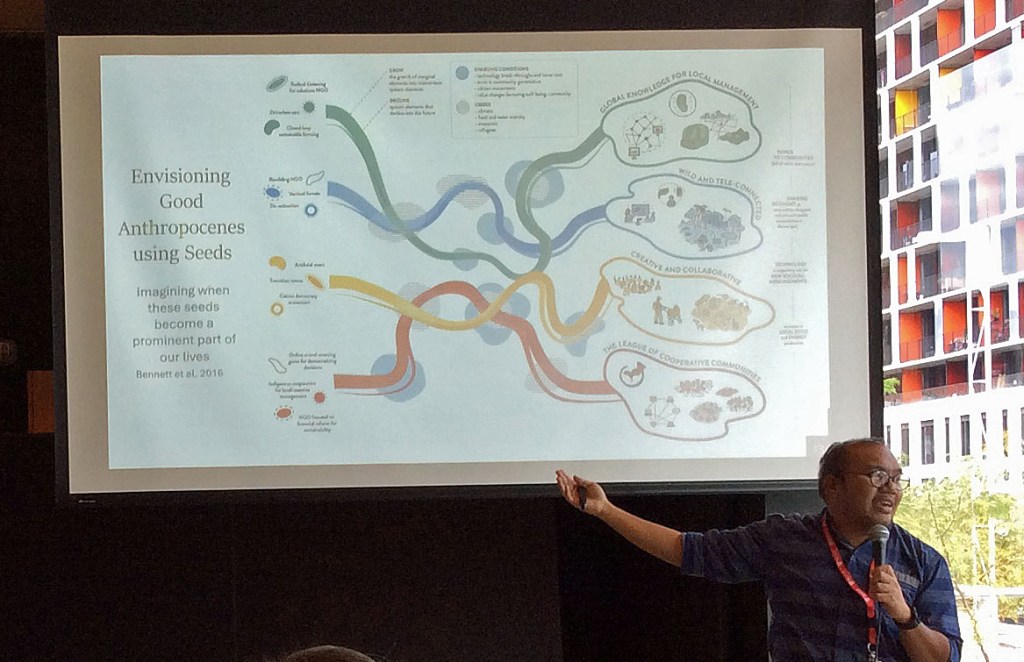

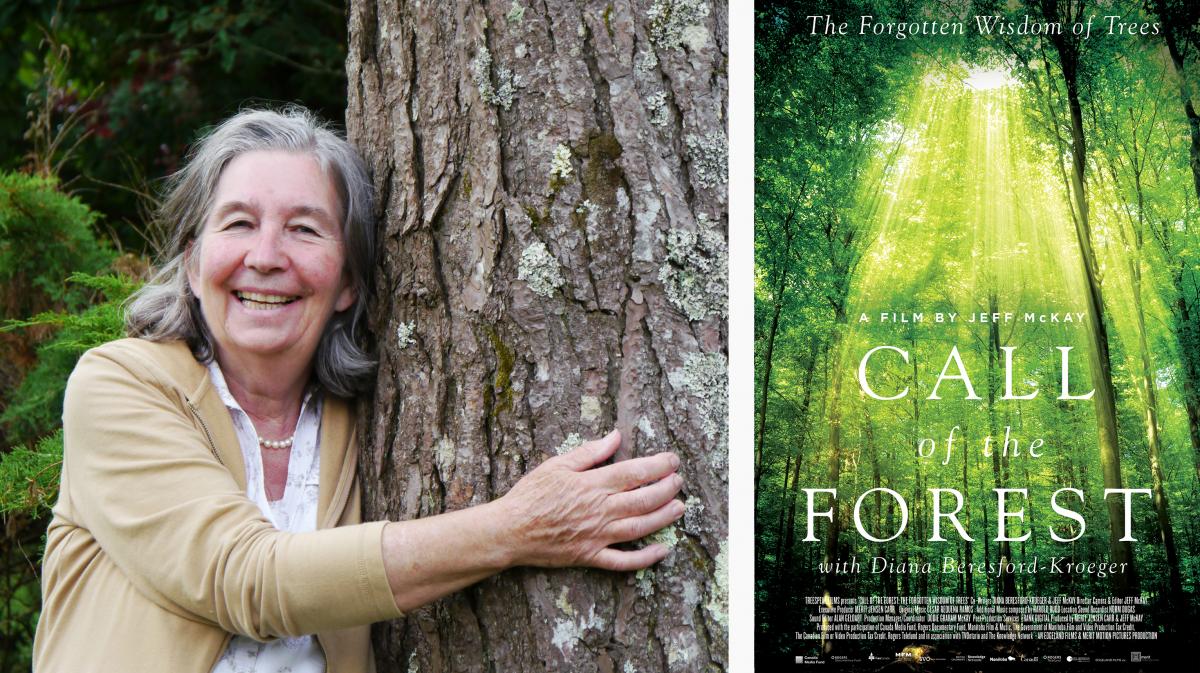

At every turn, I made contacts across disciplines and interests and had stimulating and meaningful conversations. I discovered many hopeful ‘stories’ of Montreal and elsewhere on hopeful visions and endeavors. These included “Seeds of good Anthropocenes” (small ground-rooted projects and initiatives aimed at shaping a future that is just, prosperous, and sustainable); turning scientific research into hopeful stories; and world building as resistance. I talked with artistic creators, students doing masters in Hopepunk literature and co-panelists on all manner of subjects from urban encampments, greening and rewilding Montreal, to how Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring informed a main character in Liu Cixin’s novel The Three Body Problem.

Conversations often led to an acknowledgement of art as an effective means of expression and creative therapy in the context of the climate crisis. I met creatives such as Marc-Olivier Lamothe and his colleagues at MAPP and had the chance to experiment first hand with his creative tools. I had wonderful discussions with storytelling visual artist Alina Gutierrez Mejia of Visual Versa, whose evolving mural of each day’s events was truly mesmerizing to watch—and rather revealing.

In future, I’ll post more on these and other creatives I encountered at the conference.

Program for Montreal 2140

THURSDAY morning began with an introduction by BDE Director Frédéric Fabry.

This was followed by a panel entitled Hopeful Stories Across Science and Fiction, in which I participated, along with fellow writers Su J. Sokol (author of Zee), Alyx Dellamonica (author of Gamechanger), Rich Larson (author of Annex and Ymir), Genevieve Blouin (author of Le mouroir des anges) and Andrea Renaud Simard (author of Les Tisseurs). The panel was moderated by McGill geographer Renee Sieber and McGill urban planner Lisa Bornstein.

After lunch, a panel entitled Faculty Workshop: Turning Research into Hopeful Stories was moderated by McGill researcher Kevin Manaugh and Annalee Newitz (journalist and author of Four Lost Cities). McGill researchers included: Caroline Wagner (bioengineering), Hillary Kaell (anthropology and religious studies); Jim Nicell (civil engineering); Sébastien Jodoin (law); and Michael Hendricks (biology).

The faculty panel was followed by the Student Workshop, Hope and the Future, led by McGill students Tom Nakasako, Rachel Barker, Tatum Hillier, and Lydia Lepki.

Annalee Newitz closed the day with their keynote presentation Worldbuilding Is Resistance that explored the dystopia binary of environmental science fiction. A theme to which the next keynote by Kim Stanley Robinson would touch on as well.

FRIDAY morning started with Elson Galang and Elena Bennett (McGill University), who led the Seeds of Good Anthropocenes Workshop, which introduced the concept of seeds programs then further explored through breakout discussion groups they moderated.

This was followed by faculty-led Teaching and Learning for Hopeful Futures Workshop, in which McGill instructors from varied disciplines (including education, political science, environment, urban planning and planetary sciences) discussed translating science into hopeful narratives.

I then participated in a roundtable of authors, scholars, researchers and planners entitled Telling the Story of the Future, moderated by Chris Barrington-Leigh (McGill BSE/Health and Social Policy). The roundtable included fellow authors Alyx Dellamonica and Su J. Sokol. Other participants of the roundtable included Stephanie Posthumus (languages, literatures, cultures at McGill), Jayne Engle (public policy at McGill) Richard Sheamur (urban planning at McGill), and limnologist Irene Gregory-Eaves (biology at McGill).

The final keynote was given by Kim Stanley Robinson (author of New York 2140 and The Ministry of the Future).

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit