What is to give light must endure burning —Victor Frankl

Deer Lake Park, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

“Any writing lays the writer open to judgment about the quality of his work and thought,” writes Ralph Keyes, author of The Courage to Write. “The closer [the writer] gets to painful personal truths, the more fear mounts—not just about what he might reveal, but about what he might discover should he venture too deeply inside. But to write well, that’s exactly where we must venture.”

So, why do it, then? Why bother? Is it worth it to make yourself totally vulnerable to the possible censure and ridicule of your peers, friends, and relatives? To serve up your heart on a platter to just have them drag it around as Stevie Nicks would say?…

Welcome to the threshold of your career as a writer. This is where many aspiring writers stop: in abject fear, not just of failure but of success. The only difference between those that don’t and those that do, is that the former come to terms with their fears, in fact learn to use them as a barometer to what is important.

“Everyone is afraid to write,” says Keyes. “They should be. Writing is dangerous…To love writing, fear writing and pray for the courage to write is no contradiction. It’s the essence of what we do.”

Unravelling the Secret…

How do you get past the fear of being exposed, past the anticipated disappointment of peers, past the terror of success?

The answer is passion. If you are writing about something you are passionate about, you will find the courage to see it through. “The more I read, and write,” says Keyes:

The more convinced I am that the best writing flows less from acquired skill than conviction expressed with courage. By this I don’t mean moral convictions, but the sense that what one has to say is something others need to know.—Ralph Keyes

This is ultimately what drives a writer to not just write but to publish: the need to share one’s story, over and over again. To prevail, persist, and ultimately succeed, a writer must have conviction and believe in his or her writing. You must believe that you have something to say that others want to read. Ask yourself why you are a writer. Your answer might surprise you.

Every writer is an artist. And every artist is a cultural reporter. One who sometimes holds the world accountable. “Real art,” says Susan Sontag, “makes us nervous.”

The first step, then, is to acknowledge your passion and own it. Flaunt it, even. Find your conviction, define what matters and explore it to the fullest. You will find that such an acknowledgement will give you the strength and fortitude to persist and persevere, particularly in the face of those fears. Use the fears to guide you into that journey of personal truths. Frederick Busch described it this way: “You go to dark places so that you can get there, steal the trophy and get out.”

John Steinbeck, author of Grapes of Wrath, said:

If there is a magic in story writing, and I am convinced that there is, no one has ever been able to reduce it to a recipe that can be passed from one person to another. The formula seems to lie solely in the aching urge of the writer to convey something he feels important to the reader.—John Steinbeck

Finding Success Through Meaning

Victor Frankl survived Auschwitz to become an important neurologist and psychiatrist of our time and to write Man’s Search for Meaning.

Blogger Gavin Ortlund wrote: “What gripped me most about [Frankl’s] book, and has stayed with me to this day, is not the horror and barbarity of his experiences in concentration camps—when you pick up a book about the holocaust, you expect that. What really struck me was Frankl’s repeated insistence that even there, in the most inhumane and horrific conditions imaginable, the greatest struggle is not mere survival. The greatest struggle is finding meaning. As I was reading, I was struck with this thought: going to a concentration camp is not the worst thing that can happen to a person. The worst that can happen to a person is not having a transcendent reason to live. Life is about more than finding comfort and avoiding suffering: it’s about finding what is ultimate, whatever the cost.”

Victor Frankl wisely said:

The more you aim at success and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. Success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side effect of one’s personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. Then you will live to see that in the long-run—in the long-run, I say!—success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think about it.—Victor Frankl

Frankl is talking about passion. “If you long to excel as a writer,” says Margot Finke, author of How to Keep Your Passion and Survive as a Writer, “treasure the passion that is unique within yourself. Take the irreplaceable elements of your life and craft them into your own personal contribution to the world.” It’s what has you up to 2 am, pounding the keys. It follows you down the street and to work with thoughts of another world. It puts a notebook and pen in your hand as you drive to the store, ready to record thoughts about a character, scene or place. “For the passionate, writing is not a choice; it’s a force that cannot be denied.”

Deer Lake, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Finke says it astutely: You need to be passionate about everything to do with your book—the writing and rewriting, your critique group, your research, your search for the best agent/editor, plus your query letter. Not to mention the passion that goes into promoting your book. Nothing less will assure your survival—and success—as a writer.

Follow your inner moonlight, don’t hide the madness—Allen Ginsberg, American poet

This article is an excerpt from The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now! by Nina Munteanu

References:

Finke, Margot. 2008. “How to Keep Your Passion and Survive as a Writer.” In: The Purple Crayon, http://www.underdown.org/mf_ writing_passion

Frankl, Victor. (1946) 1997. Man’s Search for Meaning. Pocket Books. 224 pp.

Keyes, Ralph. 1999. The Writer’s Guide to Creativity. Writer’s Digest, 1999.

Munteanu, Nina. 2009. The Fiction Writer: Get Published, Write Now. Starfire World Syndicate. 294pp

Ortlund, Gavin. 2008. “Frankl, the holocaust and meaning.” In: Let Us Hold Fast. http://gro1983.blogspot.com/2008/02/frankl-holocaust-and-meaning.html

Slonim Aronie, Nancy. 1998. Writing from the Heart: Tapping the Power of Your Inner Voice. Hyperion. 256pp.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Writer Timea Noemi selected

Writer Timea Noemi selected

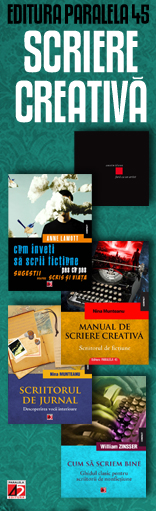

Timea Noemi also recommended the Romanian translated version of

Timea Noemi also recommended the Romanian translated version of

Cu plecere, Timi!

Cu plecere, Timi! My father is originally from Romania and grew up in Bucharest. So, I was delighted to attend the launch of

My father is originally from Romania and grew up in Bucharest. So, I was delighted to attend the launch of  Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist, limnologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Part 2 of the Beginning Novelist will focus on language.

Part 2 of the Beginning Novelist will focus on language. Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Some years ago, I was interviewed by Michael Stackpole (New York Times bestselling author of over 40 novels, including “I, Jedi” and “Rogue Squadron”) and Michael Mennenga (CEO of “Slice of Sci-Fi”) on

Some years ago, I was interviewed by Michael Stackpole (New York Times bestselling author of over 40 novels, including “I, Jedi” and “Rogue Squadron”) and Michael Mennenga (CEO of “Slice of Sci-Fi”) on  We talked about my book “

We talked about my book “

Here is an excerpt from

Here is an excerpt from