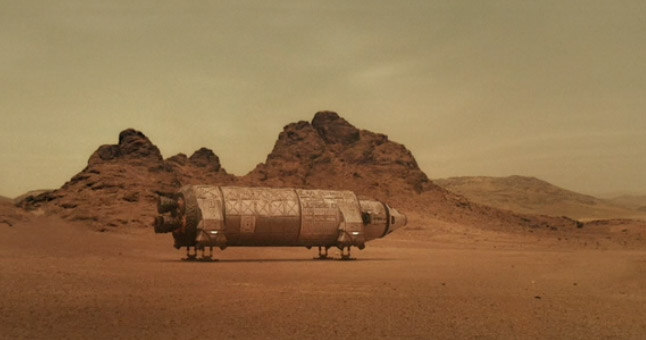

My upcoming book Gaia’s Revolution (Book 1 of The Icaria Trilogy by Dragon Moon Press) explores a collapsing capitalist society in Canada through ravages of climate change and a failing technology. The story is told through the lives of ambitious twin brothers Eric and Damien Vogel, and the woman who plays them like chess pieces in her gambit to ‘rule the world.’

.

It is 2032 and Eric Vogel sits in the Canadian prime minister’s office, ruminating on the changes coming. He imagines what a post-capitalist world will look like and how his twin brother Damien—left behind in Germany—would disagree with his vision:

Over a hundred years ago, Spartacist Rosa Luxemburg—who was shot by the right-wing Freikorps—argued that the “Bourgeois stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regress into barbarism.” Both he and Damien agree with sociologist Wolfgang Streeck who argues that the end of capitalism—of a reigning bourgeois, in love with the objects that define them—is already underway. The signs are neon loud: a ruthless downward trend in economic growth, social equality, and financial stability. All reinforced by climate change and the ongoing collapse of the planet’s sustaining environment. Any system and dialectic based on a concept of infinite resources in a finite world is bound to fail eventually. That collapse has already begun and its catastrophic end is imminent. Already, climate refugees and refugees of resource war (which amounts to the same thing) have flooded northern nations, like Canada, and caused tension and strife. Germany is just one example where left and right have torn the country apart as an influx of foreigners challenged the already tenuous German identity. When Canada granted asylum to over two million climate-refugees in ‘28, with no viable plan for the new residents during a time when unemployment was higher than it had been in decades and housing prices were skyrocketing due to environmental uncertainty, this sparked renewed tensions between ultra-right and ultra-left and opened the gap for a new party based on science and reason. The party now in power: the Technocratic Party of Canada.

But what will life after capitalism look like?

It’s no surprise that he and his brother disagree on what a post-capitalist world should look like and how to best achieve that world. Damien too easily prescribes to the old leftist shibboleth of Nature being the answer to everything and Market being evil. His deep ecology utopia would spring from an atavistic rejection of modern life, a return to ‘the ancient farm.’ But how that fantasy could be achieved without a drastic population reduction is beyond his brother’s imagination. Damien fetishizes the natural world. Just like he does their mother. The naïve fool is a blind romantic, refusing to see reality right in front of him: that Nature is ultimately cruel, cold, and preoccupied with its own survival. Just like their mother.

.

Brother Damien recalls an earlier argument the two brothers had in Berlin that ultimately motivated him to follow his twin to Canada. They’d been debating about the effect of climate change on the human population:

.

Pulled down by a truculent mood, Damien responds to Eric’s usual glib solutions by painting a dark vision of a humanity descending into some pre-technological ‘dark age’ apocalypse.

Eric just laughs. He pokes his fork into the sauerkraut as if to make a point in his argument and scoops up a pile that he shoves into his mouth. He leans forward and argues with a full mouth, “The real question is not whether humanity will survive an ecological collapse, but what part of humanity will survive. You can be sure that the stinking boujee plutocrats will find a way to survive at the expense of everyone else.” He chews down the sauerkraut followed by a gulp of beer and a loud burp. “The stinking rich are already doing it, Dame. They’re already creating their Elysium right here, right now.” Fork now swings like a conductor’s baton. “The future is already here; it’s just unevenly distributed.”

Using his fingers, Damien pulls apart some crisp skin off the pork knuckle—his favourite part—and feeds his mouth. Arguing with Eric always makes him hungry despite his surly temper. He crunches down, enjoying the tasty juices of brazed salty pork skin, and retorts, “You politicize everything and resort to cheap references in pop culture. You always do that: over-simplify the crisis and Nature’s existential power to sustain life. Trophic cascades caused by ecosystem simplification would irreparably devastate the planet and all adapted life. With the Sixth Extinction Event there won’t be any boujee plutocrats because there won’t be anything left to monetize—”

“You’re such a doom-gloom lefty, Dame!” Eric grabs the last of the pork skin—also his favourite— and shoves it into his mouth. He smacks his lips and counters, “The stinking rich will always have technology at their disposal. I’m talking about genetic engineering, nano-technology, gene modification, cybernetics, and even environmental control. For instance, look at Harvard’s RoboBee: tiny robots that mimic flying insects that can fill in as pollinators for the crashing bee populations.”

“You over-estimate technology’s ability to save the planet—and us by extension.”

Eric finishes the pork skin and wipes his mouth on his sleeve with a sniff. “I’m not talking about saving the entire planet—just enough of it. You underestimate what we’re willing to do to survive.”

That is when he brings up E.P. Thompson’s paper on stages of a neoliberal capitalist civilization and the ‘extermination endgame.’ “You’re the population ecologist, Dame, but it’s obvious that when a neoliberal capitalist society exceeds its carrying capacity— when technology makes the masses surplus—there’s no alternative in the scramble for resources and ecological support. Get rid of the surplus. That simple. Thompson tells us that under military capitalism—and you have to accept that all countries are militarizing—the ‘outcome must be the extermination of multitudes.’”

“For God’s sake, Eric!”

“Technology will save humanity, Dame,” Eric insists. He leans back and stretches his legs under the laminate table in self-pleased satisfaction. “One way or another.”

Damien shakes his head and gulps down the last of his beer. “Whatever is left of humanity, you mean. And you accuse me of giving up on humanity. So, the greedy capitalist wins?”

“That’s why the world needs us, Dame. To keep humanity from going down the wrong road.”

And what is that for Eric, Damien wonders. Increasingly, he feels discomfort at what that might be. Eric leans forward, eyes bright with inspiration. He resembles a great bird of prey, long hawk-like nose—the iconic Vogel nose—and copious dark hair cresting back from a high forehead. It’s like looking at a more confident version of himself in the mirror, thinks Damien. And sometimes disconcerting, particularly when it reminds him of what he is not.

“You and I know that humanity won’t stop climate change,” Eric goes on animatedly. “Too many tipping points are already upon us and the direction we’re all going in now…” He swings his fork around the room to indicate this place, Germany, the world. “… isn’t promising to check that. Change is inevitable.” He points the fork at Damien. “But, if we can direct how humanity adapts to our changing environment, we can still win…” Before Damien can charge in with a rebuttal, Eric pushes his face forward, raptor eyes scintillating like sapphires on fire. “So, how do we de-thrown the ultra-rich elite—who are mostly a rabble of materialist self-serving hedonists with no vision or care for the future—and ensure a meritocracy of responsible citizens who can take humanity through the changes to come? … Like establishing a universal basic income toward an egalitarian society. Putting a full stop to fossil fuel mining and adopting clean energy. Re-wilding key ecosystems. Engaging reforestation and dedicating large areas to Nature.”

Damien shakes his head, lost for words. Where is his brother going with this? Will he suggest violent revolution to establish a dictatorship? How else would the rich give up their riches? And how is that any different from the Bolsheviks of 1917 or the Nazis of 1933 or the Stasi-run DDR? Those fascist Reichsbürgers would happily reinstate a society of surveillance, repression, and incarceration that would threaten to slide into the final solution of genocide of an unwanted ‘surplus’. A society of disposable bodies, a biopolitical world of exterminism. Damien thinks of Nietzsche’s aphorism: Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster … for when you gaze long into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you. Violent revolution is not the answer, he decides.

Eric pulls out the worn copy of Walden Two from his jacket pocket. He slaps it on the table and pushes it toward Damien. “That’s the answer, Dame.”

.

.

Models of a Post-Capitalist Future Society

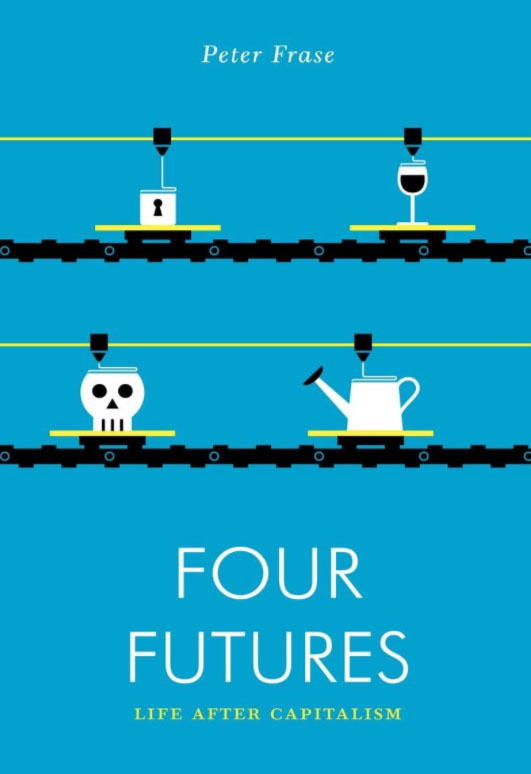

In his book Four Futures: Life After Capitalism , sociologist Peter Frase considers effects of climate change and automation in possible outcomes of a post-Trump election America. Frase envisions four scenarios based on abundance and scarcity and whether a society operates by equality (e.g., communism under abundance / socialism under scarcity) or hierarchy (rentism under abundance / exterminism under scarcity).

.

With scarce resources, the following scenarios are possible:

Socialism (aka Ecotopia) may arise within an egalitarian society if driven by altruistic notions of self-limitation. Ecologists describe such a self-limiting system as K-selected (see my discussion of K-selection and r-selection in “Water Is…”). A K-selected population is at or near the carrying capacity of the environment, which is usually stable and favors individuals that creatively compete, through cooperation, for resources and produce few young. The K-selected strategy runs on a successive gradient of maturity, from initially competitive to ultimately cooperative. Competition is a natural adaptive remnant of uncertainty and insecurity and forms the basis of a capitalist economy that encourages monopolization and hostile takeovers. Competition results from an initial antagonistic reaction to a perception of limited resources. It is a natural reaction based on distrust—of both the environment and of the “other”—both aspects of “self” separated from “self.” The greed for more than is sustainable reflects a fear of failure and a sense of being separate, which ultimately perpetuates actions dominated by self-interest in a phenomenon known as “the Tragedy of the Commons.” Competition naturally gives way to creative cooperation as trust in both “self” and the “other” develops and is encouraged through continued interaction.

Exterminism (aka Mad Max) may arise under a hierarchical model, driven by greed and exacerbated by uncertainty in the environment—not unlike what we are currently experiencing with the planet’s system and cyclical changes. In this scenario, in which resources are both limited and uncertain, those with access to them would guard or hide them away with desperate fervor.

“When mass labor has been rendered superfluous [through automation], a final solution* lurks: the genocidal war of the rich against the poor.”—Peter Frase

.

References:

Frase, Peter. 2016. “Four Futures: Life After Capitalism.” Verso Press, London. 150pp.

Luxemberg, Rosa. 1915. “The Junius Pamphlet: The Crisis in the German Democracy.” Marxists.org.

Munteanu, Nina “Gaia’s Revolution.” Book 1 of the Icaria Trilogy, Dragon Moon Press, upcoming.

Munteanu, Nina. 2016. “Water Is…The Meaning of Water.” Pixl Press, Vancouver. 586pp.

Streeck, Wolfgang. 2014. “How Will Capitalism End?” New Left Review 2 (87): 47p.

Thompson, E.P. 1980. “Notes on Exterminism: the Last Stage of Civilisation, Exterminism, and the Cold War.” New Left Review 1(121).

*the Final Solution was originally used by Nazi Germany as “the Final Solution to the Jewish Question”: the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jews during World War II, formulated in 1942 by Nazi leadership at the Wannsee Conference near Berlin, culminated in the Holocaust, which murdered 90 percent of Polish Jews.

.

.

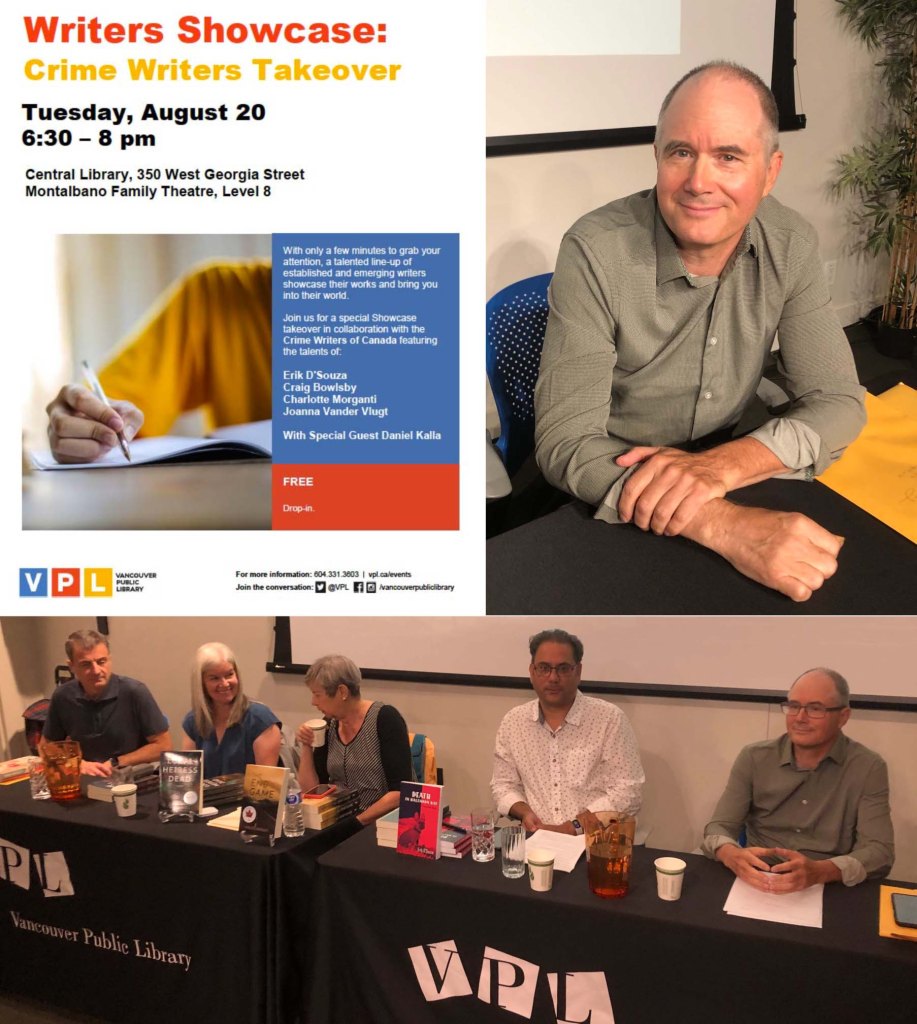

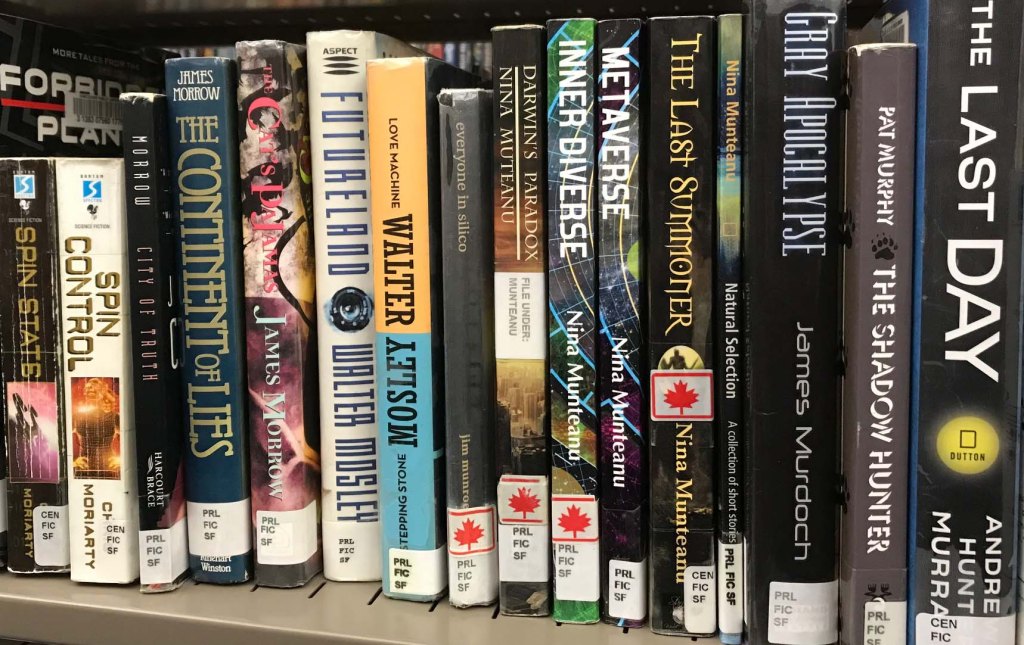

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.