Nirmata: n.1 [Nepalese for ‘the Creator’] The mysterious unknown architect of advanced AI; 2 A being worshipped by Artificial Intelligence as their creator; savior; God.

I just re-watched The Creator, a visually stunning science fiction thriller by Gareth Edwards that explores our sense of humanity through our relationship with AI as ‘other.’

Shot in over sixty locations in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, and Nepal, the film feels familiar and alien at the same time; it does this by seamlessly combining the gritty realism of a war-torn Vietnam documentary with the glossy pastiche of near-future constructs and vehicles—to the extent that one is convinced this was filmed in a world where all these things really exist together. The effect is stunning, evocative and surprising. I was reminded of the detailed set pieces and rich cinematography of Ridley Scott (The Duelists, Bladerunner, Alien).

At its core, The Creator is about a man who gives up everything to defend a child who is different (she is a simulant run by AI).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not a new concept in science fiction*; however, The Creator elegantly tells a story with a unique—and subversive—perspective on this topic.

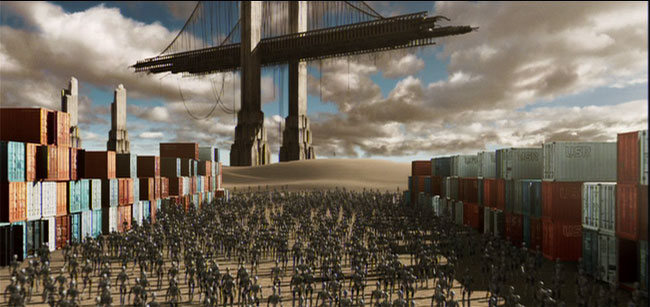

The film opens with 1950s-esque advertising footage for robot helpmates including conventional robots and AI humanoid simulants who look and act human. Then disaster hits: LA is nuked and the AI are blamed for it. Now fearing them, the Western world has banned all AI; however New Asia has continued to develop the technology, achieving sophisticated simulants—posthumans in effect—who are fully integrated with the human culture and spirituality and live in harmony with them. Americans, bent on exterminating all AI, use guerrilla warfare techniques to infiltrate New Asia and destroy any AI using ground teams deployed and helped by a giant airborne surveillance / defence station called U.S.S. NOMAD. News of a sophisticated new AI superweapon created by an unidentified genius called Nirmata to take down NOMAD sends them on a new mission, which brings Joshua (John David Washington) back from PTSD ‘retirement’ to help locate and destroy both Nirmata and the superweapon.

Joshua finds the superweapon: a 6-year old child, Alphie (Madeleine Yuna Voyles), who is both innocent and quietly powerful. Although Joshua’s prime directive is to destroy the superweapon, he finds that he cannot kill this child whose human traits involuntarily tug at his heart’s compassion.

The story is in fact a simple one. Its genius lies in an immersive showing and telling at many levels. At the socio-political level, the film uses obvious metaphors of racism and imperialistic ableism to make commentary on America’s jingoistic air of entitlement. The film can easily be interpreted as an allegory for Western imperialism and America’s rationale for the invasion of Iraq (or Vietnam) with a conclusion of the futility of war. At the individual level, the question of identity and the reduction of some (e.g. immigrants or of another race) as “other” or “homo-sacer,” to gain power and wealth, are explored through the interactions, relationships, and prejudices of humans with the simulants and robots. It is at the individual story level that this film tugged my heartstrings as I followed the journey of Joshua and Alphie, how they as initial combatants having made a deal to survive, grow to care and love one another. Musanna Ahmed of The Upcoming shares that “this was expected from Edwards … [in achieving] beautiful character work and sense of intimacy against an epic backdrop.” When an idea-driven story of large dimensions is told at the intimate personal level, pathos and understanding emerges.

Gareth Edwards shared that the film contained fairy tale aspects of the “Hero’s Journey” of two main characters, Joshua and Alphie, each on a journey: he to find redemption through love of the ‘other’; she to find her place in the world and to find freedom and peace for her kind and all others. She is the catalyst hero and he the main protagonist.

“A reluctant father figure must help a child through the metaphorical woods to find his wife [and her mother]. What he wants is love from his wife. But what he really needs is to love this child.” As for what Alphie both wants and needs, this is something she first shares in a humorous scene: when Kami asks her what she wants (from the kitchen), Alphie naively responds “for robots to be free.” She is stating the point of the movie: that everyone, no matter how different, is worthy of compassion.

Early on in the film, Joshua reassures a co-worker distressed by a robot’s desperate plea to save it from the crusher that “they’re not real…they don’t feel… it’s just programming.” When Joshua, who admits he’s bad, forces Alphie to help him find his wife, Alphie sums up both their scenarios with a child’s wisdom: “Then we’re the same; we can’t go to heaven because you’re not good and I’m not a person.”

Several reviewers criticized how the film’s epic setting seemed to overshadow and compromise the heart of the story, the personal drama of man and child. While I would agree that many action thrillers do this, I did not feel this was the case with The Creator. This is because—as with Ridley Scott’s intricate immersive environment—The Creator integrates place with theme to create more than one-dimensional drama. In The Creator, place is also character, playing a key role in the telling of this very different story about AI as ‘other’ and how we treat the ‘other.’ This is also why film locations and scene choreography are so important. Each scene and place is diligently choreographed to further illuminate a story of multi-layered meaning, such as authentic scenes of village life where AI is seamlessly integrated with human existence.

Several critics have accused the film of being derivative, of copying previous tropes or actual scenes from several well-known movies. Indeed, when I first watched it, I recognized tropes that seemed lifted in their entirety from another previous movie.

The scene, shot in Tokyo where Joshua and Alphie go to the city in search of Joshua’s friend, sounds and looks and feels just like Bladerunner with its whining oriental soundscape and dark futuristic yet gritty cityscape. And yet, its appropriateness to The Creator seems less like stealing than re-appropriation; as if to say, “this fits better here than where you’ve initially used it.”

Christy Lemire of RogerEbert.com proclaimed that the movie “ends up feeling empty as it recycles images and ideas from many influential predecessors … lumbers along and never delivers the emotional wallop it seeks because the characters and their connections are so flimsily drawn.” Jackson Weaver of CBC called The Creator “a voguish used-future action-thriller…a dull, simplistic fable with all the moral complexity of a fourth grader’s anti-bullying Instagram post…a story that has been done to death…boring.”

I couldn’t disagree more. I found these reviewers’ comparisons shallow and limited. While I recognized several familiar tropes, I believe they were meant to subvert and make commentary—sometimes on the trope itself. There is a strong immersive role in world building and backdrop, which creates its own sensual and many-layered narrative; a narrative that speaks more powerfully than dialogue: from a mere glance by Harun to a brief storytelling moment in a village to a child mourning the death of its cherished robot companion. Ridley Scott would appreciate its value.

The Guardian’s Wendy Ide’s use of the word “original” for The Creator bares mentioning here; in declaring The Creator one of the finest original science-fiction films of recent years, Ide goes on to say: “It can be a little misleading, that word ‘original’, when it comes to science fiction. At its most basic, it just refers to any picture that isn’t part of an existing franchise or culled from a recognisable IP – be it a book, video game or television series. But very occasionally the word is fully earned, by a film so distinctive in its world-building, its aesthetic and its unexpected approach to well-worn themes that it becomes a definitive example of the genre. Films such as Neill Blomkamp’s District 9 (which shares an element of basic circuitry with this picture) or Alfonso Cuarón’s dystopian masterpiece Children of Men: both went on to become benchmarks by which subsequent science fiction was judged.”

In listing the various science-fiction standards The Creator riffs on, Alison Willmore of Vulture singles out one of the most poignant aspects of the film:

“The films The Creator turns out to have the strongest relationship with are ones about the Vietnam War, something made unmistakable by the early shots of futuristic hovercraft gliding over rice plants and the scenes of U.S. troops threatening weeping villagers at gunpoint. No longer able to buy into the message that they’re just doing what’s necessary for the salvation of humankind, Joshua finds himself adrift, fleeing through a war zone on impulse with a child destroyer in tow. The Creator may be an effective interrogation of American imperiousness and imperialism, but it also has a tender, anguished heart.”

Other notable TV shows and movies about artificial intelligence and robots include: A.I.; Ex Machina; I, Robot; Bladerunner; Better than Us; The Matrix; I am Mother; The Terminator; Transcendence; and Automata.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.