Twin brothers—a brilliant scientist and a gifted engineer—escape the growing racial violence of Berlin, to ‘peaceful’ Canada in a rivalry to control the evolution of the human race.

.

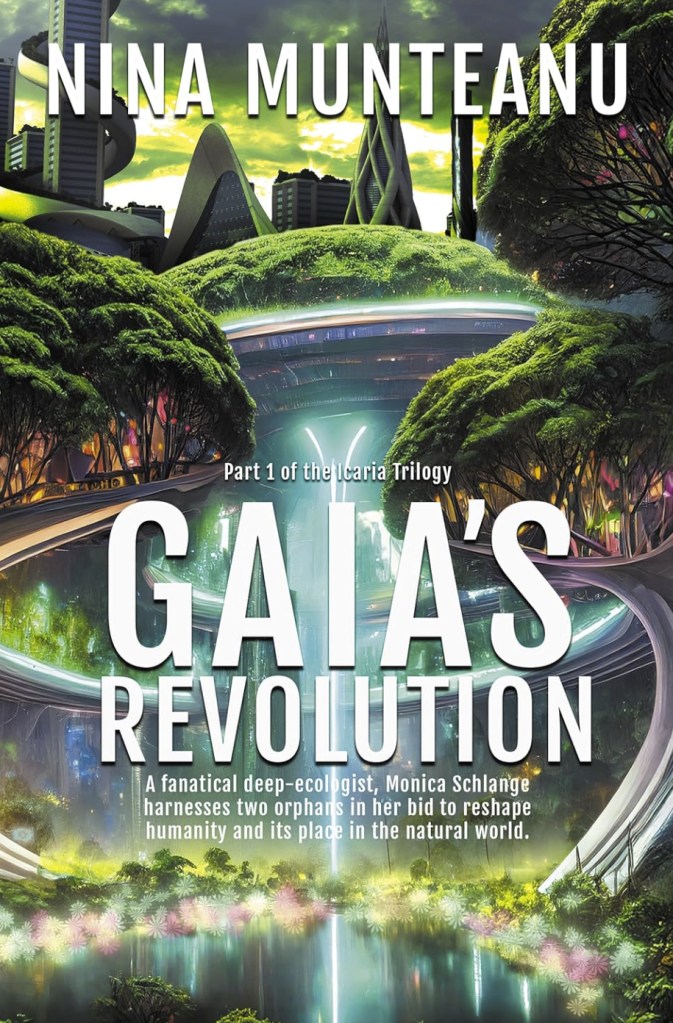

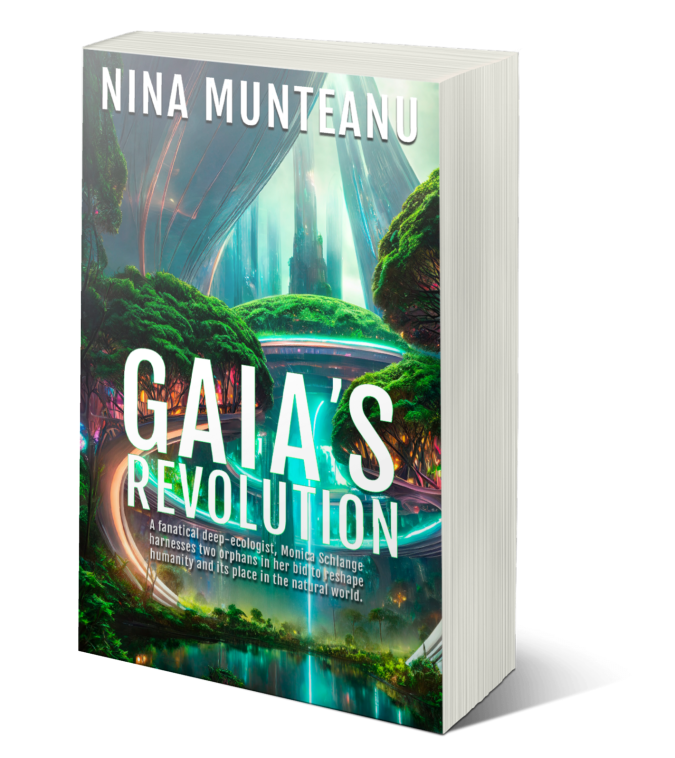

My novel Gaia’s Revolution, the first of The Icaria Trilogy—releasing March 10, 2026, by Dragon Moon Press—explores a collapsing capitalist society in Canada through ravages of climate change, water shortages, plague, and a failing technology. The story is told through the lives of ambitious twin brothers Eric and Damien Vogel, and the woman who plays them like chess pieces in her gambit to rule the world.

.

The novel starts on December 13th, 2022, in Berlin, the day several members of the climate activist group Letzte Generation* to which Damien belongs, are raided by police who seize their computers and phones. Damien is a quiet scholar, an introvert and deep ecologist*, devoted to the teachings of Arne Næss and George Sessions, who promoted an environmental philosophy of eight basic principles of deep ecology. Næss and Sessions advocated that all living beings have intrinsic value, independent of their utility to human needs. Their philosophy has become a movement that promotes a holistic, eco-centric worldview demanding radical, structural changes to human society to prioritize nature’s flourishing.

.

.

Damien later meets with his extrovert anarchist brother in Treffpunkt, near the university campus, and they argue ideology and revolution. Eric contends that the only way humanity will survive is to adapt to climate change by somehow overthrowing the bourgeois plutocrats through violent revolution: preventing the small ruling class carving out a comfortable life for itself while the rest of the world suffers terrible deprivation. Eric pulls out the worn copy of B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two from his jacket pocket, slaps it on the table and pushes it toward Damien. “That’s the answer, Dame.”

Each brother plans to create a new humanity: Eric’s plan is to control humanity through gene manipulation and behaviour engineering (aka Walden Two); Damien’s plan is to draw on deep ecology and use environmental triggers with biotechnologies to empower humanity with physical/chemical abilities to adapt to climate and its changing environment via transhumanist AI.

Neither addresses the elephant in the room: population. Only a much-reduced population will ensure success for either plan.

To this point, Eric, who is far more cynical and ruthless, thinks Damien naïve and feckless in his deep ecological view:

Damien too easily prescribes to the old leftist shibboleth of Nature being the answer to everything and Market being evil. His deep ecology utopia would spring from an atavistic rejection of modern life, a return to ‘the ancient farm.’ But how that fantasy could be achieved without a drastic population reduction is beyond his brother’s imagination. Damien fetishizes the natural world. Just like he does their mother. The naïve fool is a blind romantic, refusing to see reality right in front of him: that Nature is ultimately cruel, cold, and preoccupied with its own survival. Just like their mother.–Eric Vogel, Gaia’s Revolution

.

.

Eight Basic Principles of Deep Ecology*

In 1984, ecologists Arne Næss and George Sessions set out the following Basic Principles of Deep Ecology:

- The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman Life on Earth have value in themselves (synonyms: intrinsic value, inherent value). These values are independent of the usefulness of the non-human world for human purposes.

- Richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves.

- Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs.

- The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of nonhuman life requires such a decrease.

- Present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening.

- Policies must therefore be changed. These policies affect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures. The resulting state of affairs will be deeply different from the present.

- The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent value) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great.

- Those who subscribe to the foregoing points have an obligation directly or indirectly to try to implement the necessary changes.

.

.

Eric plans to address the 5th Basic Principle of Deep Ecology—present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive and the situation is rapidly worsening— by using nefarious means to meet the 4th Basic Principle of Deep Ecology: the flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population and the flourishing of nonhuman life requires such a decrease. With a reduced population, he plans to make the remaining principles (e.g. 6th and 7th) realizable through his behaviour engineering.

But Eric hasn’t accounted for fanatical deep ecologist / eco-terrorist Monica Schlange in his plan… (More on this shapeshifting character in Part 2).

.

.

You can pre-order the ebook of Gaia’s Revolution by Dragon Moon Press on Amazon. Release date is March 10, 2026. The print version will release soon after. Book 2 (Angel of Chaos) and Book 3 (Darwin’s Paradox) of theThe Icaria Trilogy are already available in both ebook and print form.

.

.

References:

Munteanu, Nina. 2026. “Gaia’s Revolution, Part 1 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 369 pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2010. “Angel of Chaos, Part 2 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 518 pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2007. “Darwin’s Paradox, Part 3 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 294 pp.

Sessions, George, Bill Devall. 2000. “Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered.” Gibbs Smith. 267pp.

Skinner, B.F. 1948. “Walden Two” The Macmillan Company, New York. 301pp.

.

Terminology:

*Deep Ecology: An environmental philosophy and social movement advocating that all living beings have intrinsic value, independent of their utility to human needs. Coined by Arne Næss in 1972, it promotes a holistic, ecocentric worldview—often termed “ecosophy”—that demands radical, structural changes to human society to prioritize nature’s flourishing.

*Letzte Generation: a prominent European climate activist group, founded in 2021, known for its acts of civil disobedience—such as roadblocks, defacing art, and vandalizing structures—to pressure governments on climate action. The term was chosen because they considered themselves to be the last generation before tipping points in the earth’s climate system would be reached. They are mostly active in Germany, Italy, Poland and Canada. In Germany, they have faced accusations of forming a criminal organization, leading to police raids.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. For the latest on her books, visit www.ninamunteanu.ca. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.