Story is place, and place is character—Nina Munteanu

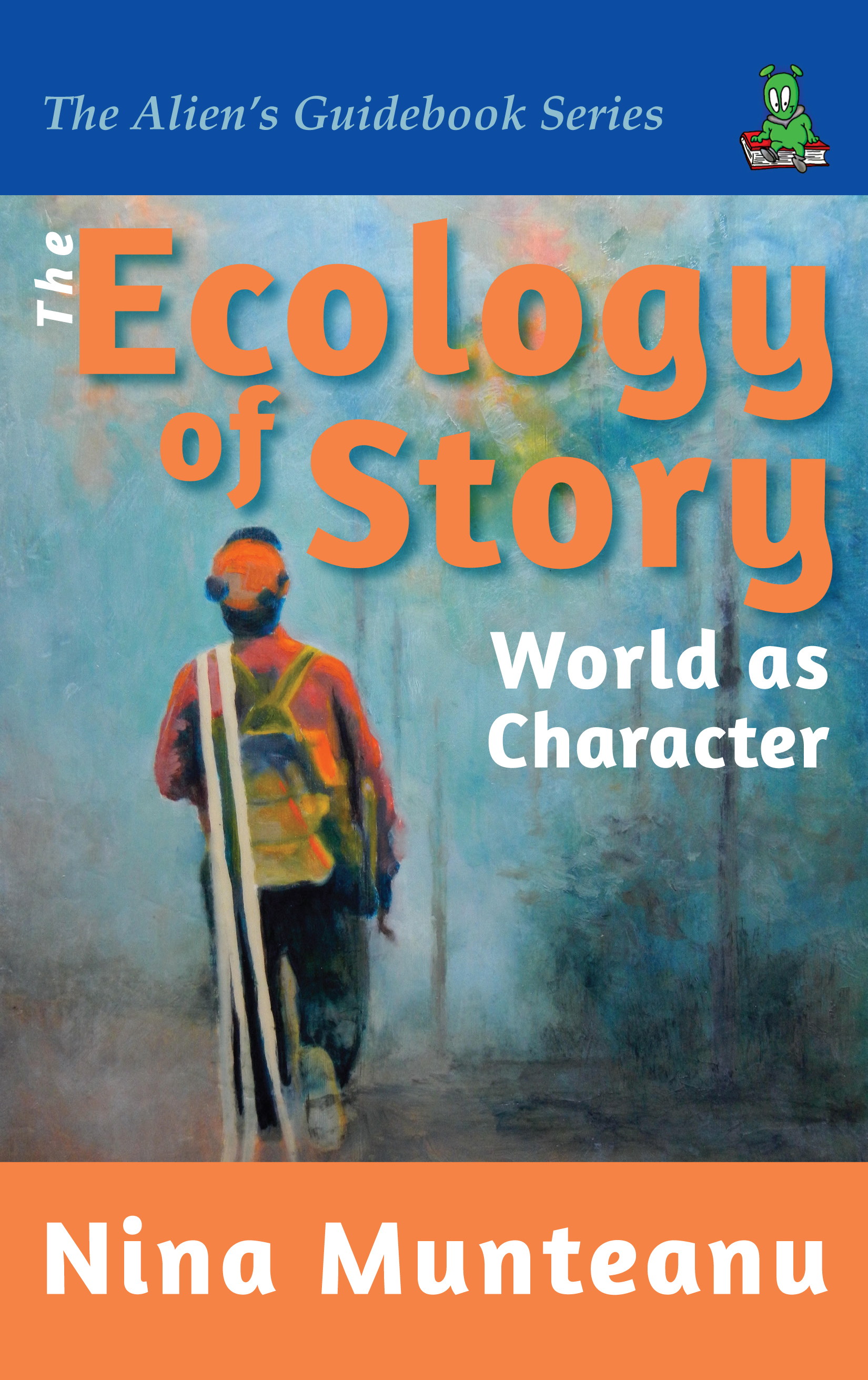

I remember a wonderful conversation I had several years ago at a conference with another science fiction writer on weird and wonderful protagonists and antagonists. Derek knew me as an ecologist—in fact I’d been invited to do a lecture at that conference entitled “The Ecology of Story” (also the name of my writing guidebook on treating setting and place as a character). We discussed the role that ecology plays in creating setting that resonates with theme and how to provide characters enlivened with metaphor.

I remember a wonderful conversation I had several years ago at a conference with another science fiction writer on weird and wonderful protagonists and antagonists. Derek knew me as an ecologist—in fact I’d been invited to do a lecture at that conference entitled “The Ecology of Story” (also the name of my writing guidebook on treating setting and place as a character). We discussed the role that ecology plays in creating setting that resonates with theme and how to provide characters enlivened with metaphor.

Derek was fascinated by saprotrophs and their qualities. Saprotrophs take their nutrition from dead and decaying matter such as decaying pieces of plants or animals by dissolving them and absorbing the energy through their body surface. They accomplish this by secreting digestive enzymes into the dead/decaying matter to absorb the soluble organic nutrients. The process—called lysotrophic nutrition—occurs through microscopic lysis of detritus. Examples of saprotrophs include mushrooms, slime mold, and bacteria.

I recall Derek’s eagerness to create a story that involved characters who demonstrate saprotrophic traits or even were genuine saprotrophs (in science fiction you can do that—it’s not hard. Check out Costi Gurgu’s astonishing novel Recipearium for a thrilling example). I wonder if Derek fulfilled his imagination.

I recall Derek’s eagerness to create a story that involved characters who demonstrate saprotrophic traits or even were genuine saprotrophs (in science fiction you can do that—it’s not hard. Check out Costi Gurgu’s astonishing novel Recipearium for a thrilling example). I wonder if Derek fulfilled his imagination.

I think of what Derek said, as I walk in my favourite woodland. It is early spring and the river that had swollen with snow melt just a week before, now flows with more restraint. I can see the cobbles and clay of scoured banks under the water. Further on, part of the path along the river has collapsed from a major bank scour the previous week. The little river is rather big and capricious, I ponder; then I consider that the entire forest sways to similar vagaries of wind, season, precipitation and unforeseen events. Despite its steadfast appearance the forest flows—like the river—in a constant state of flux and change, cycling irrevocably through life and death.

Cedar tree (photo by Nina Munteanu)

As I’m writing this, the entire world struggles with life and death in the deep throws of a viral pandemic. COVID-19 has sent many cities into severe lock down to prevent viral spread in a life and death conflict. I’ve left the city and I’m walking in a quiet forest in southern Ontario in early spring. The forest is also experiencing life and death. But here, this intricate dance has seamlessly partnered death and decay with the living being of the forest. Without the firm embrace of death and decay, life cannot dance. In fact, life would be impossible. What strikes me here in the forest is how the two dance so well.

Cedar log, patterns in sapwood (photo by Nina Munteanu)

I walk slowly, eyes cast to the forest floor to the thick layer of dead leaves, and discover seeds and nuts—the promise of new life. I aim my gaze past trees and shrubs to the nearby snags and fallen logs. I’m looking for hidden gifts. One fallen cedar log reveals swirling impressionistic patterns of wood grain, dusted with moss and lichen. Nature’s death clothed in beauty.

The bark of a large pine tree that has fallen is riddled with tiny beetle holes drilled into its bark. Where the bark has sloughed off, a gallery of larval tracks in the sapwood create a map of meandering texture, form and colour.

White pine bark scales with tiny beetle bore holes, Little Rouge, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Beetle larval tracks in pine sapwood (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Nearby, another giant pine stands tall in the forest. Its roughly chiselled bark is dusted in lichens, moss and fungus. The broad thick ridges of the bark seem arranged like in a jigsaw puzzle with scales that resemble metal plates. They form a colourful layered mosaic of copper to gray and greenish-gray. At the base of the tree, I notice that some critter has burrowed a home in a notch between two of the pine’s feet. Then just around the corner, at the base of a cedar, I spot several half-eaten black walnuts strewn in a pile—no doubt brought and left there by some hungry and industrious squirrel who prefers to dine here.

The forest is littered with snags and fallen trees in different stages of breakdown, decomposition and decay. I spot several large cedar, pine, oak and maple snags with woodpecker holes. The snags may remain for many decades before finally falling to the ground.

Fallen Heroes, Mother Archetypes & Saprophyte Characters

Woodpecker hole in a snag (photo by Nina Munteanu)

The forest ecosystem supports a diverse community of organisms in various stages of life and death and decay. Trees lie at the heart of this ecosystem, supporting a complex and dynamic cycle of evolving life. Even in death, the trees continue to support thriving detrivore and saprophytic communities that, in turn, provide nutrients and soil for the next generation of living trees. It’s a partnership.

Decomposition and decay are the yin to the yang of growth, writes Trees for Life; and together they form two halves of the whole that is the closed-loop cycle of natural ecosystems.

Snags and rotting logs on the forest floor provide damp shelter and food for many plants and animals. Most are decomposers, including earthworms, fungi, and bacteria. As the wood decays, nutrients in the log break down and recycle in the forest ecosystem. Insects, mosses, lichens, and ferns recycle the nutrients and put them back into the soil for other forest plants to use. Dead wood is an important reservoir of organic matter in forests and a source of soil formation. Decaying and dead wood host diverse communities of bacteria and fungi.

Turkey tail fungus, Little Rouge woodland (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Mother Archetypes

Wood tissues of tree stems include the outer bark, cork cambium, inner bark (phloem), vascular cambium, outer xylem (living sapwood), and the inner xylem (non-living heartwood). The outer bark provides a non-living barrier between the inner tree and harmful factors in the environment, such as fire, insects, and diseases. The cork cambium (phellogen) produces bark cells. The vascular cambium produces both the phloem cells (principal food-conducting tissue) and xylem cells of the sapwood (the main water storage and conducting tissue) and heartwood.

Forest ecologists defined five broad stages in tree decay, shown by the condition of the bark and wood and presence of insects and other animals. The first two stages evolve rapidly; much more time elapses in the later stages, when the tree sags to the ground. These latter stages can take decades for the tree to break down completely and surrender all of itself back to the forest. A fallen tree nurtures, much like a “mother” archetype; it provides food, shelter, and protection to a vast community—from bears and small mammals to salamanders, invertebrates, fungus, moss and lichens. This is why fallen trees are called “nursing logs.”

Uprooted tree covered in fungi, lichen and moss, Little Rouge, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Heralds, Tricksters and Enablers

Rotting maple log (photo by Nina Munteanu)

I stop to inspect another fallen tree lying on a bed of decaying maple, beech and oak leaves. When a fallen tree decomposes, unique new habitats are created within its body as the outer and inner bark, sapwood, and heartwood decompose at different rates, based in part on their characteristics for fine dining. For instance, the outer layers of the tree are rich in protein; inner layers are high in carbohydrates. This log—probably a sugar maple judging from what bark is left—has surrendered itself with the help of detrivores and saprophytes to decomposition and decay. The outer bark has mostly rotted and fallen away revealing an inner sapwood layer rich in varied colours, textures and incredible patterns—mostly from fungal infestations. In fact, this tree is a rich ecosystem for dozens of organisms. Wood-boring beetle larvae tunnel through the bark and wood, building their chambers and inoculating the tree with microbes. They open the tree to colonization by other microbes and small invertebrates. Slime molds, lichen, moss and fungi join in. The march of decay follows a succession of steps. Even fungi are followed by yet other fungi in the process as one form creates the right condition for another form.

Rotting maple log, covered in carbon cushion fungus, Little Rouge, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Most hardwoods take several decades to decompose and surrender all of themselves back to the forest. In western Canada in the westcoast old growth forest, trees like cedars can take over a hundred years to decay once they’re down. The maple log I’m studying in this Carolinian forest looks like it’s been lying on the ground for a while, certainly several years. The bark has fragmented and mostly fallen away, revealing layers of sapwood in differing stages of infestation and decay. Some sapwood is fragmented and cracked into blocks and in places looks like stacked bones.

Black lines as though drawn by a child’s paintbrush flow through much of the sapwood; these winding thick streaks of black known as “zone lines” are in fact clumps of dark mycelia, which cause “spalting,” the colouration of wood by fungus. According to mycologist Jens Petersen, these zone lines prevent “a hostile takeover by mycelia” from any interloping fungi. Most common trees that experience spalting include birch, maple, and beech. Two common fungi that cause spalting have colonized my maple log. They’re both carbon cushion fungi.

Spalting through zone lines by carbon cushion fungus, Little Rouge, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Hypoxylon fungus (photo N. Munteanu)

Brittle cinder (Kretzschmaria deusta) resembles burnt wood at maturity. Deusta means “burned up” referring to the charred appearance of the fungus. Hypoxylon forms a “velvety” grey-greenish cushion or mat (stroma). As the Hypoxylon ages, it blackens and hardens and tiny, embedded fruitbodies (perithecia) show up like pimples over the surface of the crust.

Green and Blue Stain fungus (photo N. Munteanu)

Much of the exposed outer wood layer looks as though it has been spray painted with a green to blue-black layer. The “paint” is caused by the green-stain fungus (Chlorociboria) and blue-stain fungus (Ceratocystis). The blue-green stain is a metabolite called xylindein. Chlorociboria and Ceratocystis are also spalter fungi, producing a pigment that changes the color of the wood where they grow. While zone lines that create spalting don’t damage wood, the fungus responsible most likely does.

Spalting is common because of the way fungi colonize, in waves of primary and secondary colonizers. Primary colonizers initially capture and control the resource, change the pH and structure of the wood, then must defend against the secondary colonizers now able to colonize the changed wood.

Details of 16th century German bureaus containing blue-green spalted wood by the elf-cup fungus Chlorociboria aeruginascens

Wood that is stained green, blue or blue-green by spalting fungi has been and continues to be valued for inlaid woodwork. In an article called “Exquisite Rot: Spalted Wood and the Lost Art of Intarsia” Daniel Elkind writes of how “the technique of intarsia–the fitting together of pieces of intricately cut wood to make often complex images–has produced some of the most awe-inspiring pieces of Renaissance craftsmanship.” The article explores “the history of this masterful art, and how an added dash of colour arose from the most unlikely source: lumber ridden with fungus.”

Shapeshifting Characters

Moss in forest litter (photo by Nina Munteanu)

I find moss everywhere in the forest, including beneath the forest floor. Moss is a ubiquitous character, adapting itself to different situations and scenarios. Like a shapeshifter, moss is at once coy, hiding beneath rotting leaf litter, stealthy and curious as it creeps up the feet of huge cedars, and exuberant as it unabashedly drapes itself over every possible surface such as logs, twigs and rocks, and then proceeds to procreate for all to see.

Moss is a non-vascular plant that helps create soil; moss also filters and retains water, stabilizes the ground and removes CO2 from the atmosphere. Science tells us that mosses are important regulators of soil hydroclimate and nutrient cycling in forests, particularly in boreal ecosystems, bolstering their resilience. Mosses help with nutrient cycling because they can fix nitrogen from the air, making it available to other plants.

Green moss gametophyte with sporophytes growing out of it (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Mosses thrive in the wet winter and spring, providing brilliant green to an otherwise brown-gray environment. Even when covered in snow (or a bed of leaves), moss continues its growth cycle, usually in the leafy gametophyte stage. When the winter is moderate, like it is near Toronto, sporophyte structures can already appear on stalks that hold a capsule full of spores. In the spring the capsules release spores that can each create a new moss individual. Moss is quietly, gloriously profligate.

Symbiotic Characters

Many twigs strewn on the leaf-covered forest floor are covered in grey-green lichen with leaf-like, lobes. On close inspection, the lichen thallus contains abundant cup-shaped fruiting bodies. I identify the lichen as Physchia stellaris, common and widespread in Ontario and typically pioneering on the bark of twigs—especially of poplars, and alders.

Physchia stellaris lichen with fruiting bodies (apothecia), Little Rouge, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

Lichens are a cooperative character; two characters in one, really. Lichens are a complex symbiotic association of two or more fungi and algae (some also partner up with a yeast). The algae in lichens (called phycobiont or photobiont) photosynthesize and the fungus (mycobiont) provides protection for the photobiont. Both the algae and fungus absorb water, minerals, and pollutants from the air, through rain and dust. In sexual reproduction, the mycobiont produces fruiting bodies, often cup-shaped, called apothecia that release ascospores. The spores must find a compatible photobiont to create a lichen. They depend on each other for resources—from food to shelter and protection.

Forest as Character

Sunset in Niagara on the Lake (photo by Nina Munteanu)

In Far from the Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy personified trees as interpreters between Nature and humanity: from the “sobbing breaths” of a fir plantation to the stillness of trees in a quiet fog, standing “in an attitude of intentness, as if they waited longingly for a wind to come and rock them.” Trees, meadows, winding brooks and country roads were far more than back-drop for Hardy’s world and his stories. Elements of the natural world were characters in their own right that impacted the other characters in a world dominated by nature.

Place ultimately portrays what lies at the heart of the story. Place as character serves as an archetype that story characters connect with and navigate in ways that depend on the theme of the story, particularly in allegories that rely strongly on metaphor. A story’s theme is essentially the “so what part” of the story. What is at stake for the character on their journey. Theme is the backbone—the heart—of the story, driving characters to journey through time and place toward some kind of fulfillment. There is no story without theme. And there is no theme without place.

—excerpted from The Ecology of Story: World as Character

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” will be released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

I write mostly eco-fiction. Even before it was known as eco-fiction, I was writing it. My first book—

I write mostly eco-fiction. Even before it was known as eco-fiction, I was writing it. My first book— Things to consider about

Things to consider about  Water has been used as a powerful archetype in many novels. In my latest novel,

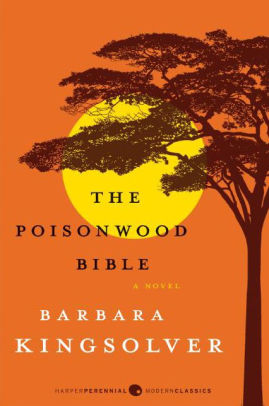

Water has been used as a powerful archetype in many novels. In my latest novel,  In these examples the environmental aspect serves as symbol and metaphoric connection to theme. They can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchel’s Gone With the Wind; the white pine forests for the Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; The animals for Beatrix Potter of the Susan Wittig Albert series.

In these examples the environmental aspect serves as symbol and metaphoric connection to theme. They can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchel’s Gone With the Wind; the white pine forests for the Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; The animals for Beatrix Potter of the Susan Wittig Albert series.

Nina: I guess that every weed was once a native somewhere. I also agree that times are changing—faster than many of us are ready for, humans included. If you were to identify with an archetype, which would you choose?

Nina: I guess that every weed was once a native somewhere. I also agree that times are changing—faster than many of us are ready for, humans included. If you were to identify with an archetype, which would you choose?

I remember a wonderful conversation I had several years ago at a conference with another science fiction writer on weird and wonderful protagonists and antagonists. Derek knew me as an ecologist—in fact I’d been invited to do a lecture at that conference entitled

I remember a wonderful conversation I had several years ago at a conference with another science fiction writer on weird and wonderful protagonists and antagonists. Derek knew me as an ecologist—in fact I’d been invited to do a lecture at that conference entitled  I recall Derek’s eagerness to create a story that involved characters who demonstrate saprotrophic traits or even were genuine saprotrophs (in science fiction you can do that—it’s not hard. Check out

I recall Derek’s eagerness to create a story that involved characters who demonstrate saprotrophic traits or even were genuine saprotrophs (in science fiction you can do that—it’s not hard. Check out

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

Jeremiah Wall, Nina Munteanu, Nancy R. Lange, Nicole Davidson, Carmen Doreal, MarieAnnie Soleil, Luis Raúl Calvo, Louis-Philippe Hébert, Melania Rusu Caragioiu, Anna-Louise Fontaine.

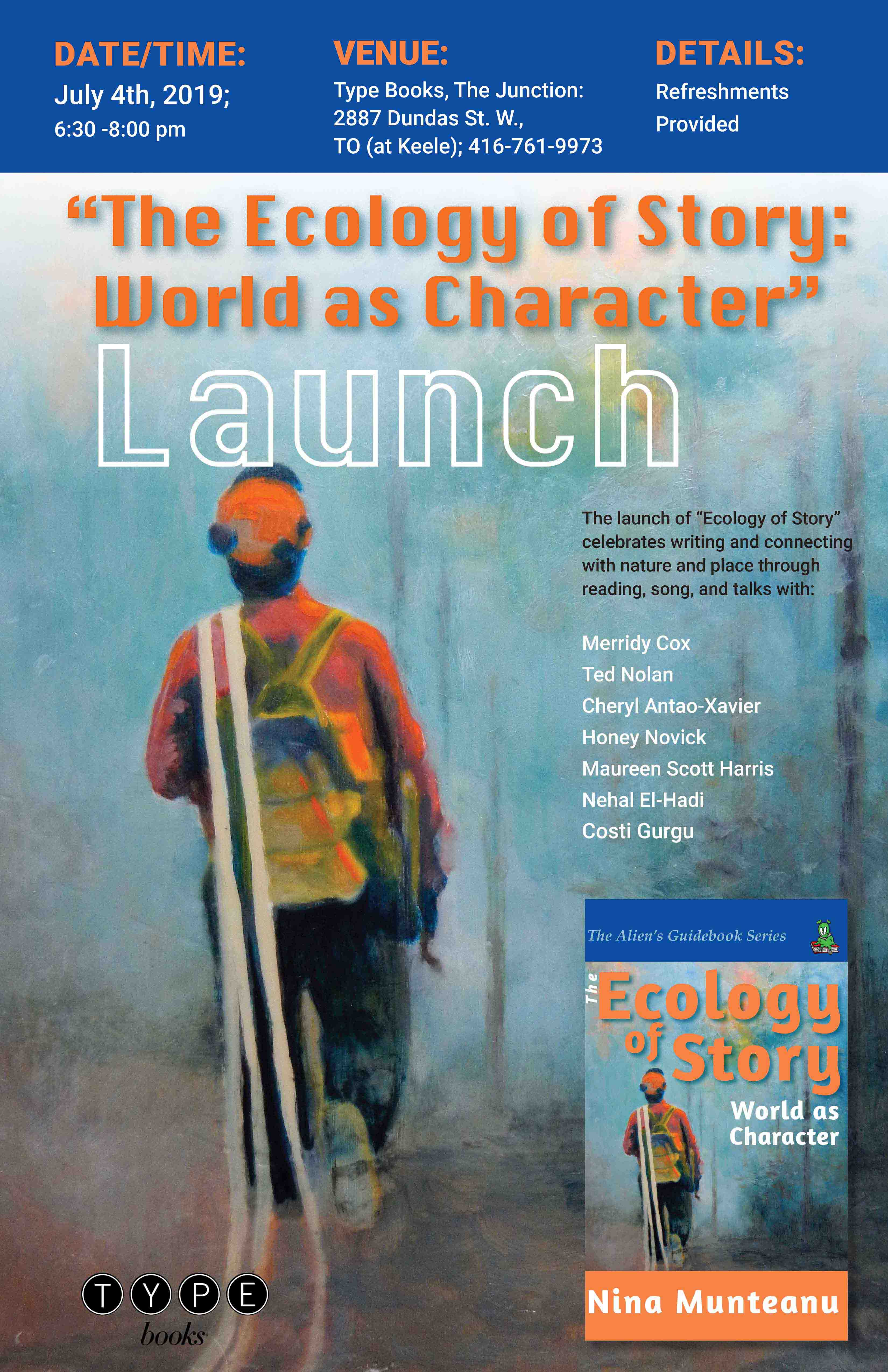

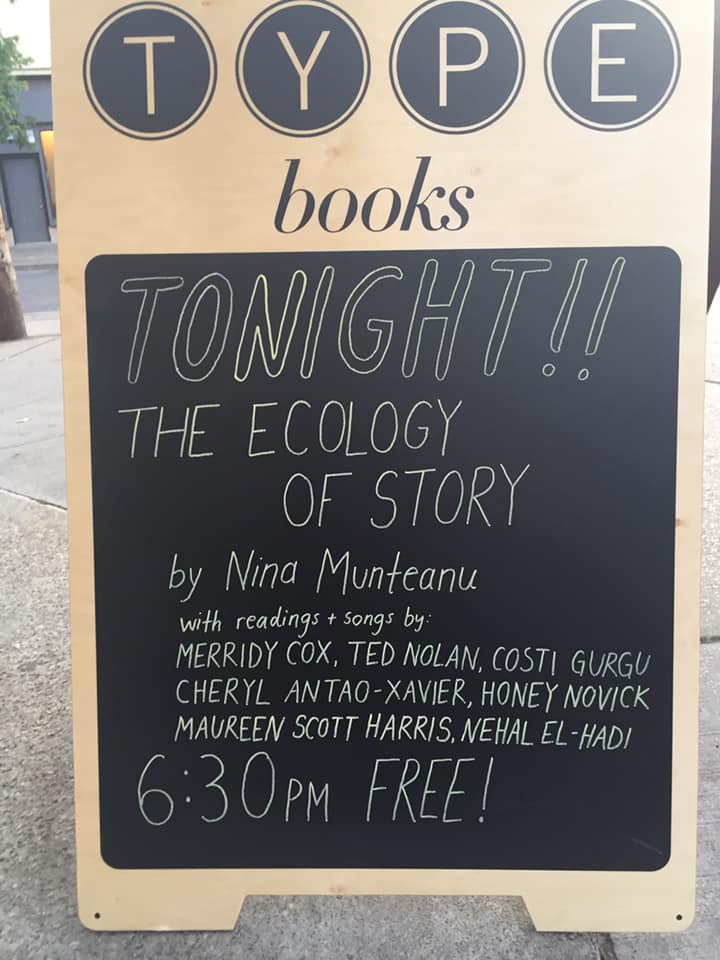

UofT instructor and writer Nina Munteanu launched the third book in her acclaimed “how to write” series at Type Books, Toronto, on July 4th, 2019. The launch of

UofT instructor and writer Nina Munteanu launched the third book in her acclaimed “how to write” series at Type Books, Toronto, on July 4th, 2019. The launch of

Honey Novick is a poet, voice teacher, singer and songwriter. Honey is the winner of the Empowered Poet Award, CAPAC, Yamaha Classical Music Competition in Japan, among others. Honey wrote music for CBC’s Morningside and sang for Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

Honey Novick is a poet, voice teacher, singer and songwriter. Honey is the winner of the Empowered Poet Award, CAPAC, Yamaha Classical Music Competition in Japan, among others. Honey wrote music for CBC’s Morningside and sang for Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau. Ted Nolan—E. Martin Nolan—is a poet, essayist, editor and voice of the trees. He teaches in the Engineering Communication Program at the University of Toronto and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics at York University. His latest work is a chapbook written in collaboration with some trees entitled: “Trees Hate Us.”

Ted Nolan—E. Martin Nolan—is a poet, essayist, editor and voice of the trees. He teaches in the Engineering Communication Program at the University of Toronto and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics at York University. His latest work is a chapbook written in collaboration with some trees entitled: “Trees Hate Us.” Maureen Scott Harris is a poet, essayist, and rare books cataloguer. A UofT grad in Library Science, she received the Trillium Book Award for poetry for Drowning Lessons and was the first non-Australian to be awarded the 2009 WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize for her essay, “Broken Mouth: Offerings for the Don River, Toronto.”

Maureen Scott Harris is a poet, essayist, and rare books cataloguer. A UofT grad in Library Science, she received the Trillium Book Award for poetry for Drowning Lessons and was the first non-Australian to be awarded the 2009 WildCare Tasmania Nature Writing Prize for her essay, “Broken Mouth: Offerings for the Don River, Toronto.” Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, researcher, editor and journalist, who explores the intersections of body, technology, and space. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, literary magazines, and forthcoming in anthologies and edited collections. She is currently a visiting scholar at York University and sessional faculty at the University of Toronto.

Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, researcher, editor and journalist, who explores the intersections of body, technology, and space. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, literary magazines, and forthcoming in anthologies and edited collections. She is currently a visiting scholar at York University and sessional faculty at the University of Toronto. Merridy Cox is a naturalist, photographer, editor, indexer and poet. She is also managing editor of Lyrical Leaf Publishing. Merridy has a degree in biology and museum studies; her poetry focuses mostly on the natural world around her; her poems and photographs are published in several literary anthologies. She has edited several books, including this one!

Merridy Cox is a naturalist, photographer, editor, indexer and poet. She is also managing editor of Lyrical Leaf Publishing. Merridy has a degree in biology and museum studies; her poetry focuses mostly on the natural world around her; her poems and photographs are published in several literary anthologies. She has edited several books, including this one! Costi Gurgu is a graphic designer and illustrator as well as an award-winning science fiction and fantasy novelist and short story writer who is published in anthologies and magazines throughout the world. He is a former lawyer and was art director for lifestyle and fashion magazines in Europe before moving to Canada. His latest novel—RecipeArium—was called the new new weird by Robert J. Sawyer and was nominated for an Aurora Award.

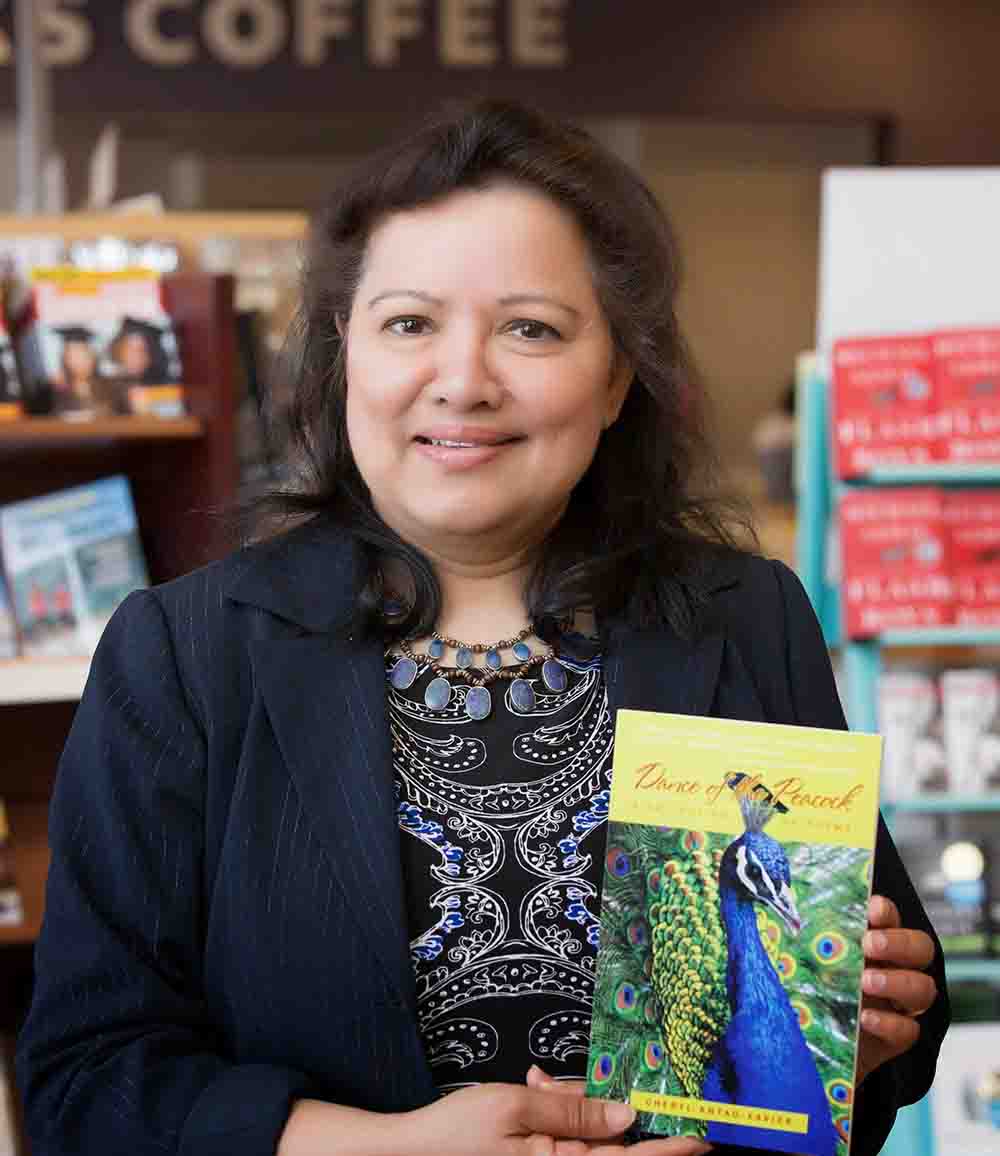

Costi Gurgu is a graphic designer and illustrator as well as an award-winning science fiction and fantasy novelist and short story writer who is published in anthologies and magazines throughout the world. He is a former lawyer and was art director for lifestyle and fashion magazines in Europe before moving to Canada. His latest novel—RecipeArium—was called the new new weird by Robert J. Sawyer and was nominated for an Aurora Award. Cheryl Antao-Xavier is an editor, interior book designer and publisher with IOWI. She has been publishing emergent writers since 2008 and continues to offer self-publishing solutions to writers and companies and organizations. She recently released her book: “Self-Publishing the Professional Way: 5 Steps from Raw Manuscript to Publishing.”

Cheryl Antao-Xavier is an editor, interior book designer and publisher with IOWI. She has been publishing emergent writers since 2008 and continues to offer self-publishing solutions to writers and companies and organizations. She recently released her book: “Self-Publishing the Professional Way: 5 Steps from Raw Manuscript to Publishing.”

She is inhumanly alone. And then, all at once, she isn’t. A beautiful animal stands on the other side of the water. They look up from their lives, woman and animal, amazed to find themselves in the same place. He freezes, inspecting her with his black-tipped ears. His back is purplish-brown in the dim light, sloping downward from the gentle hump of his shoulders. The forest’s shadows fall into lines across his white-striped flanks. His stiff forelegs play out to the sides like stilts, for he’s been caught in the act of reaching down for water. Without taking his eyes from her, he twitches a little at the knee, then the shoulder, where a fly devils him. Finally he surrenders his surprise, looks away, and drinks. She can feel the touch of his long, curled tongue on the water’s skin, as if he were lapping from her hand. His head bobs gently, nodding small, velvet horns lit white from behind like new leaves.

She is inhumanly alone. And then, all at once, she isn’t. A beautiful animal stands on the other side of the water. They look up from their lives, woman and animal, amazed to find themselves in the same place. He freezes, inspecting her with his black-tipped ears. His back is purplish-brown in the dim light, sloping downward from the gentle hump of his shoulders. The forest’s shadows fall into lines across his white-striped flanks. His stiff forelegs play out to the sides like stilts, for he’s been caught in the act of reaching down for water. Without taking his eyes from her, he twitches a little at the knee, then the shoulder, where a fly devils him. Finally he surrenders his surprise, looks away, and drinks. She can feel the touch of his long, curled tongue on the water’s skin, as if he were lapping from her hand. His head bobs gently, nodding small, velvet horns lit white from behind like new leaves.  An oligotrophic lake is basically a young lake. Still immature and undeveloped, an oligotrophic lake often displays a rugged untamed beauty. An oligotrophic lakes hungers for the stuff of life. Sediments from incoming rivers slowly feed it with dissolved nutrients and particulate organic matter. Detritus and associated microbes slowly seed the lake. Phytoplankton eventually flourish, food for zooplankton and fish. The shores then gradually slide and fill, as does the very bottom. Deltas form and macrophytes colonize the shallows. Birds bring in more creatures. And so on. Succession is the engine of destiny and trophic status its shibboleth.

An oligotrophic lake is basically a young lake. Still immature and undeveloped, an oligotrophic lake often displays a rugged untamed beauty. An oligotrophic lakes hungers for the stuff of life. Sediments from incoming rivers slowly feed it with dissolved nutrients and particulate organic matter. Detritus and associated microbes slowly seed the lake. Phytoplankton eventually flourish, food for zooplankton and fish. The shores then gradually slide and fill, as does the very bottom. Deltas form and macrophytes colonize the shallows. Birds bring in more creatures. And so on. Succession is the engine of destiny and trophic status its shibboleth.

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self- conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.

They met in the lobby of a shabby downtown Toronto hotel. Hilda barely knew what she looked like but when Hanna entered the lobby through the front doors, Hilda knew every bit of her. Hanna swept in like a stray summer rainstorm, beaming with the self- conscious optimism of someone who recognized a twin sister. She reminded Hilda of her first boyfriend, clutching flowers in one hand and chocolate in the other. When their eyes met, Hilda knew. For an instant, she knew all of Hanna. For an instant, she’d glimpsed eternity. What she didn’t know then was that it was love.  This article is an excerpt from

This article is an excerpt from