Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 biopunk science fiction novel The Windup Girl occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of ag-biotech multinational giants such as AgriGen, RedStar, and PurCal—predatory companies who have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing and sterilizing genetic manipulations. The story’s premise could very easily be described as “what would happen if Monsanto got its way?”

Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 biopunk science fiction novel The Windup Girl occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of ag-biotech multinational giants such as AgriGen, RedStar, and PurCal—predatory companies who have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing and sterilizing genetic manipulations. The story’s premise could very easily be described as “what would happen if Monsanto got its way?”

Bacigalupi’s story opens in Bangkok, “City of Angels”, now below sea level and precariously protected by a giant sea wall and pumps that run on bio-power:

It’s difficult not to always be aware of those high walls and the pressure of the water beyond. Difficult not to think of the City of Divine Beings as anything other than a disaster waiting to happen. But the Thais are stubborn and have fought to keep their revered city of Krung Thep from drowning. With coal-burning pumps and leveed labor and a deep faith in the visionary leadership of their Chakri Dynasty they have so far kept at bay that thing which has swallowed New York and Rangoon, Mumbai and New Orleans.

It’s difficult not to always be aware of those high walls and the pressure of the water beyond. Difficult not to think of the City of Divine Beings as anything other than a disaster waiting to happen. But the Thais are stubborn and have fought to keep their revered city of Krung Thep from drowning. With coal-burning pumps and leveed labor and a deep faith in the visionary leadership of their Chakri Dynasty they have so far kept at bay that thing which has swallowed New York and Rangoon, Mumbai and New Orleans.

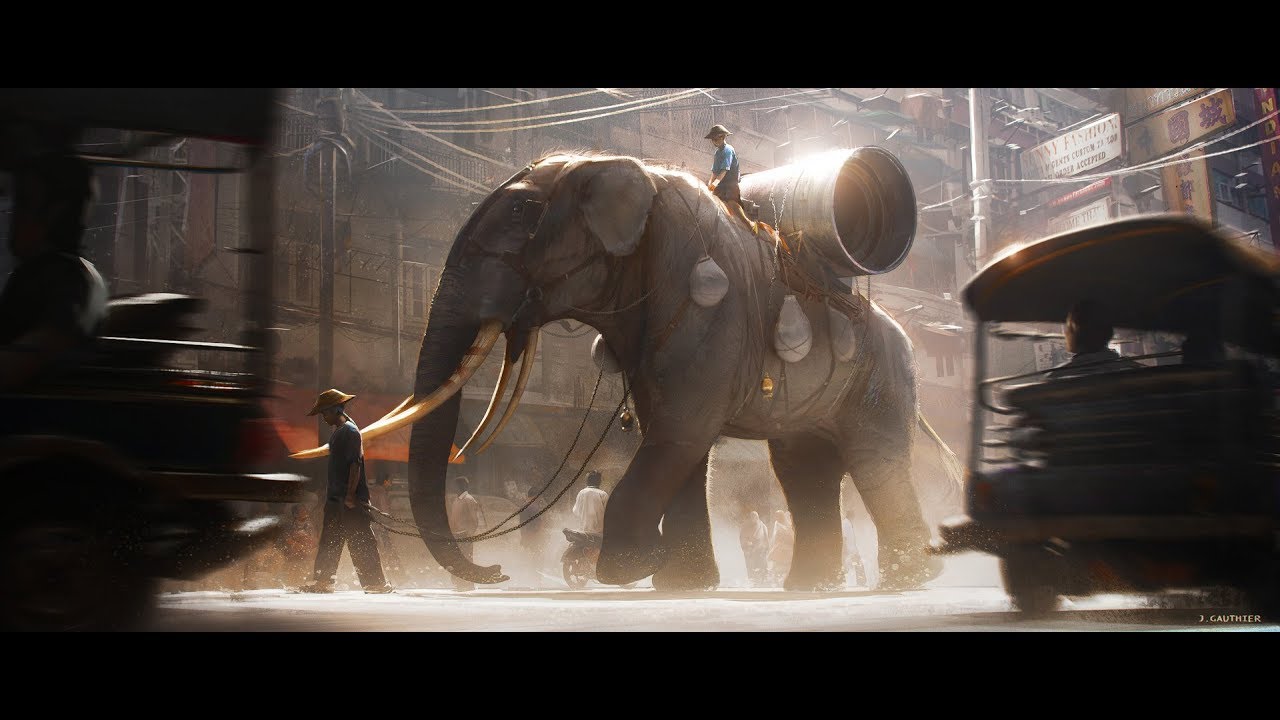

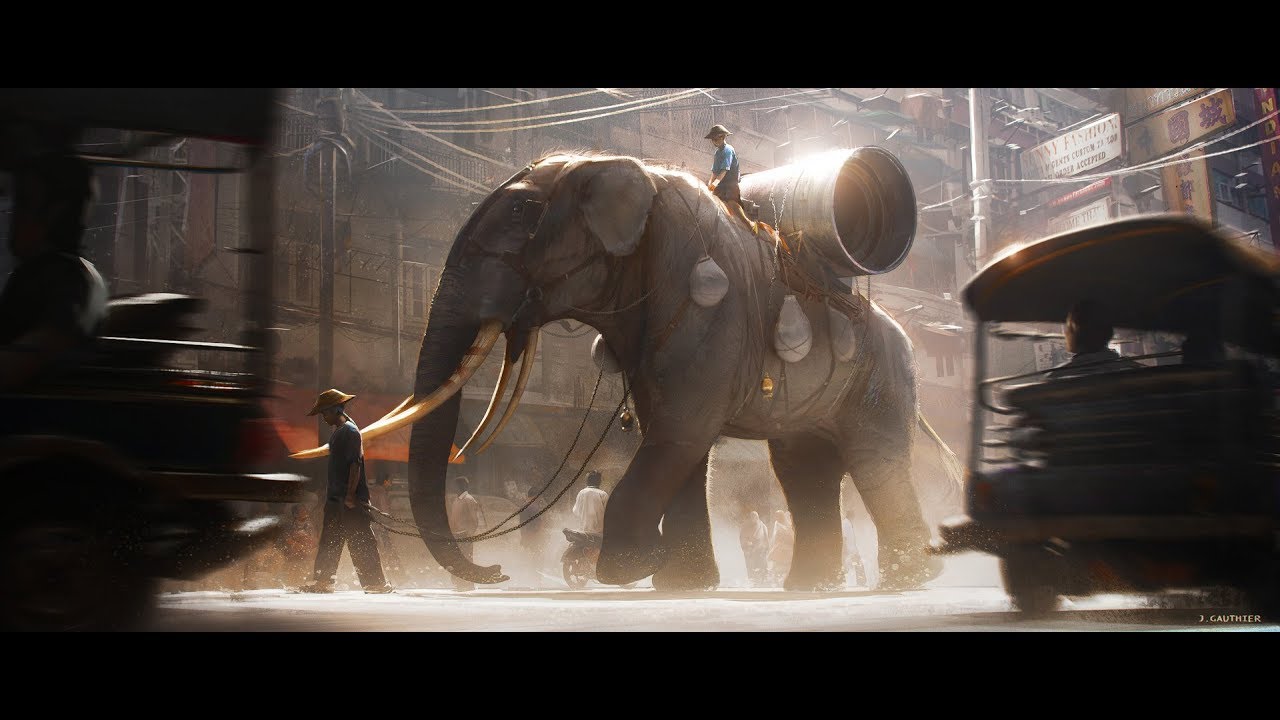

Energy storage in this post-oil society is provided by manually-wound springs using cruelly mistreated genehacked megodonts—elephant-slave labor. Biotechnology dominates via international mega-corporations—called calorie companies—that control food production through genehacked seeds. The companies use bioterrorism and economic hitmen to secure markets for their products—just as Monsanto is currently doing. Plagues (some they created, others unintended mutations) have wiped out the natural seed stock, now virtually supplanted by genetically engineered sterile plants and mutant pests such as cibiscosis, blister rust, and genehack weevil. Thailand—one of the economically disadvantaged—has avoided economic subjugation by the foreign calorie companies through some ingenuity—a hidden seedbank of diverse natural seeds—and is now targeted by the agri-corporations.

future Bangkok envisioned by Julien Gauthier

Bacigalupi’s opening entwines the clogged and crumbling city of Bangkok and its swarming beggars, slaves and laborers in a microcosm of a world spinning out of control:

Overhead, the towers of Bangkok’s old Expansion loom, robed in vines and mold, windows long ago blown out, great bones picked clean. Without air conditioning or elevators to make them habitable, they stand and blister in the sun. The black smoke of illegal dung fires wafts from their pores, marking where Malayan refugees hurriedly scald chapatis and boil kopi before the white shirts can storm the sweltering heights and beat them for their infringements.

Anderson Lake is a farang (of white race) who owns an AgriGen factory trying to mass-produce kink-springs—successors to the internal combustion engine) to store energy. The factory is in fact a cover for his real mission: to find and exploit the secret Thai seedbank with its wealth of genetic material. We later discover that Lake is an economic hitman and spy whose previous missions have destroyed entire countries for the sake of monopoly.

Emiko is an illegal Japanese “windup” (genetically modified human), owned by a Thai sex club owner, and treated as a sub-human slave. When she meets Lake, he cavalierly shares that a refuge in the remnant forests of northern Thailand exists for people like her (the “New People”); Emiko dreams of escaping her bonds to find her own people in the north. But like Bangkok itself, both protected and trapped by the wall against a sea poised to claim it—a bustling city of squalor caught up in the clash of new and old—Emiko cannot escape who and what she is: a gifted modified human—and possible herald of a sustainable future—vilified and feared by the very humanity that created her.

Bangkok’s floating market

Bangkok emerges as a central character in a story that explores the paradox of conflicting dialectics battling for survival in a violently changing world. Anyone who has spent time in Bangkok will recognize the connective tissue that holds together its crumbling remnants with ambitious chic. Just like the novel’s cheshires: genetically created “cats” (made by an agri-giant as a “toy”) that wiped out the regular cat Felis domesticus.

Cheshire Cat of “Alice in Wonderland”

Named after Alice in Wonderland’s Cheshire Cat, these crafty creatures have adapted well to Bangkok’s unstable environment. The cheshires exemplify the cost of unintended consequence (a major theme in the novel); the cheshires also reflect the paradoxical nature of a shape-shifting city of Thais, Chinese and Malaya refuges who struggle to survive in a place that is both haven and danger:

Cheshire cat disappearing

The flicker-shimmer shapes of cheshires twine, yowling and hoping for scraps … The old man’s flinch is as hallucinogenic as a cheshire’s fade—one moment there, the next gone and doubted … The devil cats flicker closer. Calico and ginger, black as night—all of them fading in and out of view as their bodies take on the colors of their surroundings.

Captain Jaidee Rojjanasukchai is a righteous white shirt—the strong arm of the Ministry of the Environment. He is a faithful Thai Buddhist, whose only weakness is his sense of invincibility borne from a mistaken sense of government integrity. Revered by fellow white shirts as the “Tiger of Bangkok,” he is incorruptible—we find out that he may be the only person in the entire place who refuses to be swayed by bribes. A true and passionate believer in the cause he is fighting for—the very survival of the environment and his people by association—Jaidee is ruthless in his raids and attacks on those who wish to open the markets of globalization and potential contamination. Early in the novel, Jaidee reflects on humanity’s impact on the ecological cycle:

All life produces waste. The act of living produces costs, hazards, and disposal questions, and so the Ministry has found itself in the centre of all life, mitigating, guiding and policing the detritus of the average person along with investigating the infractions of the greedy and short-sighted, the ones who wish to make quick profits and trade on others’ lives for it.

Bacigalupi astutely identifies the tenuous role of any government’s environment ministry—to protect and champion the environment—within a government that values its economy more highly and when, in fact, most of the time its members operate quietly in the pocket of short-sighted politicians and business men who focus myopically on short-term gain. “The symbol for the Environment Ministry is the eye of the tortoise, for the long view—the understanding that nothing comes cheap or quickly without a hidden cost,” Jaidee thinks. The United States EPA is a prime example of such paradox—in which the agency’s top executive is in fact a former industrialist who lobbied for deregulation. The current EPA no longer fulfills its role as guardian of the environment. In Canada, I have witnessed terrible conflict between one ministry with another in a game of greed vs. protection. Bacigalupi showcases this diametric with his characters Pracha (Environment) and Akkarat (Trade).

Abandoned supermarket now a giant koi pond, Bangkok

The rivalry between Thailand’s Minister of Trade and Minister of the Environment represent the central conflict of the novel, reflecting the current conflict of neo-liberal promotion of globalization and its senseless exploitation (Akkarat) with the forces of sustainability, fierce environmental protection and (in some cases) isolationism (Pracha). Given the setting and the two men vying for power, both scenarios are extreme and there appears no middle ground for a balanced existence using responsible and sustainable means. Emiko, who represents a possible future, is precariously poised; Jaidee, the single individual who refuses to succumb to the bribes of a dying civilization—is sacrificed: just as integrity and righteousness are violently destroyed when chaos threatens and engulfs.

“Windup Girl” Bangkok dam

Various reviewers of the novel identify the gaijin (foreigner) Anderson Lake as the closest thing to a protagonist. In fact, Lake never manages to rise from his avatar as the human face to the behemoth of ruthless globalization, the face of a Monsanto-look-alike. He is an unsympathetic and weak character, who—despite showing some feelings for the windup girl—connives and lacks human compassion to the end. Not a protagonist. During a meeting with the Minister of Trade, in which Lake hubristically offers “aid”, Akkarat confronts Lake on the destruction of his greedy corporation: “Ever since your first missionaries landed on our shores, you have always sought to destroy us. During the old Expansion your kind tried to take every part of us. Chopping off the arms and legs of our country…With the Contraction, your worshipped global economy left us starving and over-specialized. And then your calorie plagues came.” Lake shrugs this off and continues his aggressive exchange with the minister—sealing his fate beneath Nature’s relentless tsunami.

Twug tank, imagined by Rob Davies

Jaidee—who is brutally killed on page 197 of the novel with another 200 pages to go—remains Bacigalupi’s only character of agency worth following. The Tiger of Bangkok represents the Ministry of Environment’s hard policy of environmental protection—the only thing that kept Thailand from falling to the global mega-corporation’s plagues. With Jaidee’s demise, we tumble in free fall into a “Game of Thrones” miasma of “who goes next—I don’t care.” While I continued to read, it was more from post-traumatic shock than from eager interest. It was as though I’d lost a good friend—my safety anchor in a horrid place—and was now set adrift. I drifted, alone, amid the remaining characters—each pathetic in their own way—on a slow slide into the wrathful hell of a vengeful Nature. I found myself rooting for the cheshires and windups, experiments-turned victims-turned adapted survivors of a vast unintended consequence in human greed.

Perhaps that is what Bacigalupi intended.

Concept of megadonts in “Windup Girl”

And yet, there is unsmiling monosyllabic Kanya, Jaidee’s not-so-pure lieutenant, now promoted to his position and eager to atone for her former betrayal—we learn that she was planted as a Trade mole in Environment. Struggling to do the right thing after Jaidee’s murder, Kanya emerges as the true protagonist in the novel. As we learn more of her unfortunate history and gain a clear understanding of her complex motivations (we get no such insight into Lake), Kanya’s journey unfolds through heartbreak and redemption. Kanya picks up Jaidee’s spirit—literally—and, accompanied by his phii (his ghost), tries to settle the warring factions to gain peace for a rioting city. Of course, it doesn’t work and the gaiji devils return in full force as Akkarat hands over Thailand and its precious seedbank to the American corporations.

Happy with Akkarat’s coup, corporate mogul Carlyle says to Lake: “The first thing we do is go find some whiskey and a rooftop, and watch the damn sun rise over the country we just bought.”

Instructed to take the AgriGen gaigi to the vault and hand over the seedbank to them, “Kanya studies the people who used to be called calorie demons and who now walk so brazenly in Krung Thep, the City of Divine Beings.” Jeering and laughing with no respect, the gaiji behave like they own the place. In a sudden moment of clarity—inspired by Jaidee’s phii—Kanya then singlehandedly creates her own coup by executing the AgriGen gaigi and instructing the monks to dispatch Thailand’s precious seedbank safely to the jungle wilderness. Husked of its precious treasure, the city implodes. Floodwater pumps and locks fail to sabotage. Then the monsoons arrive. The City of Angels gives in to the sea that chases refugees into the genehack-destroyed outer forests.

Paolo Bacigalupi

While Kanya triumphs in her own personal battle, she remains less agent of change than feckless witness to Nature’s powerful force as it unfurls like a giant cheshire and sends dominoes crashing into one another.

Fittingly, Bacigalupi’s Epilogue belongs to the windup girl and the cheshires. And an uncertain future with promise of change.

And that is certainly what Bacigalupi intended.

Bangkok sunset by Julien Gauthier

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” will be released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in 2020.

Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 biopunk science fiction novel The Windup Girl occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of ag-biotech multinational giants such as AgriGen, RedStar, and PurCal—predatory companies who have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing and sterilizing genetic manipulations. The story’s premise could very easily be described as “what would happen if Monsanto got its way?”

Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2015 biopunk science fiction novel The Windup Girl occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of ag-biotech multinational giants such as AgriGen, RedStar, and PurCal—predatory companies who have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing and sterilizing genetic manipulations. The story’s premise could very easily be described as “what would happen if Monsanto got its way?” It’s difficult not to always be aware of those high walls and the pressure of the water beyond. Difficult not to think of the City of Divine Beings as anything other than a disaster waiting to happen. But the Thais are stubborn and have fought to keep their revered city of Krung Thep from drowning. With coal-burning pumps and leveed labor and a deep faith in the visionary leadership of their Chakri Dynasty they have so far kept at bay that thing which has swallowed New York and Rangoon, Mumbai and New Orleans.

It’s difficult not to always be aware of those high walls and the pressure of the water beyond. Difficult not to think of the City of Divine Beings as anything other than a disaster waiting to happen. But the Thais are stubborn and have fought to keep their revered city of Krung Thep from drowning. With coal-burning pumps and leveed labor and a deep faith in the visionary leadership of their Chakri Dynasty they have so far kept at bay that thing which has swallowed New York and Rangoon, Mumbai and New Orleans.