They came because they were afraid or unafraid, happy or unhappy. There was a reason for each man. They were coming to find something or get something, or to dig up something or bury something. They were coming with small dreams or big dreams or none at all

Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles

When I was but a sprite, and before I became an avid reader of books (I preferred comic books), I read Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles. It changed me, what I thought of books and what I felt about the power of stories. It made me cry. And perhaps that was when I decided to become a writer. I wanted to move people as Bradbury had moved me.

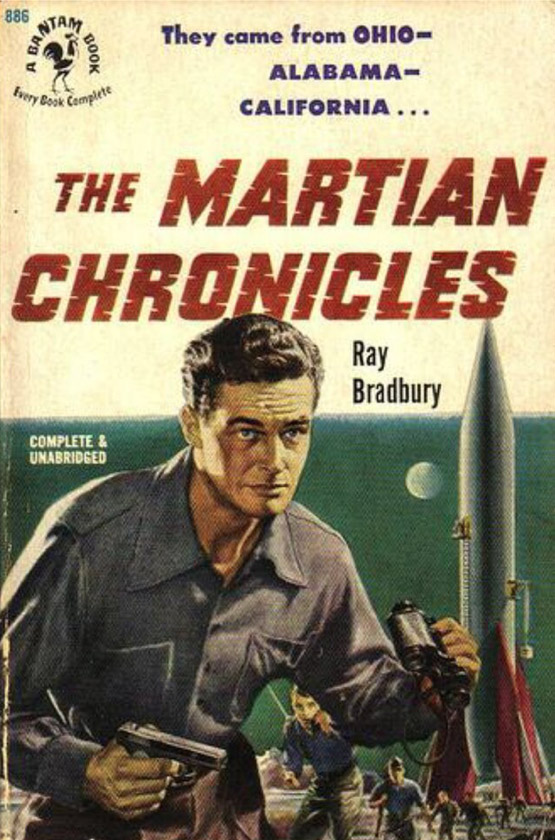

The 1970 Bantam book jacket aptly describes The Martian Chronicles as, “a poetic fantasy about the colonization of Mars. The story of familiar people and familiar passions set against incredible beauties of a new world…A skillful blending of fancy and satire, terror and tenderness, wonder and contempt.”

.

.

The Martian Chronicles isn’t really about Mars. True to Bradbury’s master metaphoric storytelling, The Martian Chronicles is about humanity. Who we are, what we are and what we may become. What we inadvertently do—to others, and finally to ourselves—and how the irony of chance can change everything. Despite the knowledge of no detectable amounts of oxygen, Bradbury gave Mars a breathable atmosphere: “Mars is a mirror, not a crystal,” he said, using the planet for social commentary rather than to predict the future.

From “Rocket Summer” to “The Million-Year Picnic,” Ray Bradbury’s stories of the colonization of Mars form an eerie tapestry of past and future. Written in the 1940s, the chronicles long with the nostalgia of shady porches with pitchers of lemonade, ponderously ticking grandfather clocks, and comfortable sofas. Expedition after expedition leave Earth to investigate and colonize Mars. Though the Martians guard their mysteries well, they succumb to the diseases that come with the rocketeers and grow extinct—not unlike the quiet disappearance of the golden toad, the Pinta giant tortoise, or the Bramble Cay melomys. Humans, with ideas often no more lofty than starting a tourist hot-dog stand, bear no regret for the native alien culture they exploit and eventually displace.

It is a common theme of human colonialism and expansionism, armed with the entitlement of privilege. Mars is India to the imperialistic British Empire. It is Rwanda or Zaire to the colonial empire of the cruel jingoistic King Leopold II of Belgium. Mars is Europe to Nazi Germany’s sonderweg. We need look no further than our own Canadian soil for a reflection of this slow violence of disrespect and apathy by our settler ancestors on the indigenous peoples of Canada.

Mars was a distant shore, and the men spread upon it in waves… Each wave different, and each wave stronger.

The Martian Chronicles

Tyler Miller of The Black Cat Moan makes excellent commentary in their 2016 article entitled “How Ray Bradbury’s ‘The Martian Chronicles’ changed Science Fiction (and Literature).” The article begins with a quote from Argentinean author Jorge Luis Borges (in the introduction to the Spanish-language translation of The Martian Chronicles: “What has this man from Illinois done, I ask myself when closing the pages of this book, that episodes from the conquest of another planet fill me with horror and loneliness?”

.

Remember, this was the 1950s … halfway through a century dominated by scientific discovery, and expansion. The 1950s saw developments in technology, such as nuclear energy and space exploration. On the heels of the end of World War II, the 1950s was ignited by public imagination on conquering space, creating technological futures and robotics. The 1950s was considered by some as the real golden age for science fiction, still a kind of backwater genre read mostly by boys and young men, that told glimmering tales of adventure, exploration, and militarism, of promising technologies, and often-androcratic societies who used them in the distant future to conquer other worlds full of strange and disposable alien beings in the name of democracy and capitalism. (In some ways, this is still very much the same. Though, it is thankfully changing…)

(Bantam 1951 1st edition cover)

Many scientists deeply involved in the exploration of the solar system (myself among them) were first turned in that direction by science fiction. And the fact that some of that science fiction was not of the highest quality is irrelevant. Ten year‐olds do not read the scientific literature.

Carl Sagan, 1978

Large idea-driven SF works that typified this time period included Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot and his Foundation series.

It was at this time that Ray Bradbury published The Martian Chronicles. Though filled with the requisite rocket ships, gleaming Martian cities, ray guns, and interplanetary conquest, from the very start—as Borges noted—The Martian Chronicles departed radically from its SF counterparts of the time.

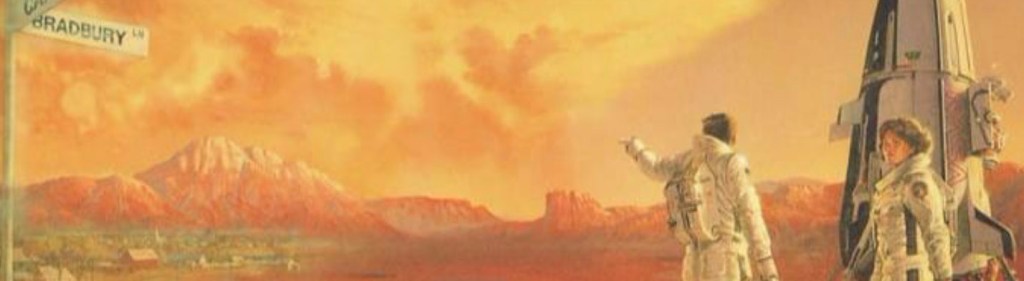

(Illustration on album cover of “Rocket Summer”, music by Chris Byman)

Instead of starting with inspiring technology or a stunning action sequence, or a challenging idea or discovery, Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles opens with a domestic scene.

One minute it was Ohio winter, with doors closed, windows locked, the panes blind with frost, icicles fringing every roof, children skiing on the slopes, housewives lumbering like great black bears in their furs along the icy streets.

And then a long wave of warmth crossed the small town. A flooding sea of hot air; it seemed as if someone had left a bakery door open. The heat pulsed among the cottages and bushes and children. The icicles dropped, shattering, to melt. The doors flew open. The windows flew up. The children worked off their wool clothes. The housewives shed their bear disguises. The snow dissolved and showed last summer’s ancient green lawns.

Rocket summer. The words passed among the people in the open air, airing houses. Rocket summer. The warm desert air changing the frost patterns on the windows, erasing the art work. The skis and sleds suddenly useless. The snow, falling from the cold sky upon the town, turned to a hot rain before it touched the ground.

Rocket summer. People leaned from their dripping porches and watched the reddening sky.

The rocket lay on the launching field, lowing out pink clouds of fire and oven heat. The rocket stood in the cold winter morning, making summer with every breath of its mighty exhausts. The rocket made climates, and summer lay for brief moment upon the land…

Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles, Rocket Summer

Bradbury’s focus was on the domestic. Housewives fighting off the ice and snow of Ohio. A Martian woman “cleaning the house with handfuls of magnetic dust which, taking all dirt with it, blew away on the hot wind.”

They had a house of crystal pillars on the planet Mars by the edge of the empty sea, and every morning you could see Mrs. K eating the golden fruits that grew from the crystal walls, or cleaning the house with handfuls of magnet dust which, taking all dirt with it, blew away on the hot wind. Afternoons, when the fossil sea was warm and motionless, and the wine trees stood stiff in the yard…you could see Mr. K in his room, reading from a metal book with raised hieroglyphs over which he brushed his hand, as one might play a harp. And from the book, as his fingers stroked, a voice sang, a soft ancient voice, which told tales of when the sea was red steam on the shore and ancient men had carried clouds of metal insects and electric spiders into battle…

This morning Mrs. K stood between the pillars, listening to the desert sands heat, melt into yellow wax, and seemingly run on the horizon.

Something was going to happen.

She waited.

Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles, Ylla

Bradbury’s gift to literature—and to his SF genre—was his use of metaphor. Unlike the science fiction of his colleagues, Bradbury’s stories are a lens to study the past and the present. According to Miller, “The Earthmen’s exploration and desolation of Mars allowed Bradbury to look not forward but backward at exploration and desolation on Earth, namely the European arrival in the New World. Just as Europeans landed in North and Central America wholly unprepared for what they found there, Bradbury’s Earthmen are unprepared time and again for the wonder and the horror of Mars. And just as European diseases decimated native people in the Americas, it is chicken-pox which wipes out the Martians.”

.

.

The back cover of the 2012 mass market paperback Simon & Schuster Reprint edition of The Martian Chronicles reads:

Bradbury’s Mars is a place of hope, dreams and metaphor—of crystal pillars and fossil seas—where a fine dust settles on the great, empty cities of a silently destroyed civilization. It is here the invaders have come to despoil and commercialize, to grow and to learn—first a trickle, then a torrent, rushing from a world with no future toward a promise of tomorrow. The Earthman conquers Mars … and then is conquered by it, lulled by dangerous lies of comfort and familiarity, and enchanted by the lingering glamour of an ancient, mysterious native race.

“Ask me then, if I believe in the spirit of the things as they were used, and I’ll say yes. They’re all here. All the things which had uses. All the mountains which had names. And we’ll never be able to use them without feeling uncomfortable. And somehow the mountains will never sound right to us; we’ll give them new names, but the old names are there, somewhere in time, and the mountains were shaped and seen under those names. The names we’ll give to the canals and the mountains and the cities will fall like so much water on the back of a mallard. No matter how we touch Mars, we’ll never touch it. And then we’ll get mad at it, and you know what we’ll do? We’ll rip it up, rip the skin off, and change it to fit ourselves.”

Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles, And the Moon be Still as Bright

“We won’t ruin Mars,” said the captain. “It’s too big and too good.”

“You think not? We Earth Men have a talent for ruining big, beautiful things.”

Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles is a profound and tender analysis of the quiet power humanity can wield unawares and how we define and treat ‘the other.’ It is a tragic tale that reflects only too well current world events where the best intended interventions can go awry. From the meddling friend who gossips to “help” another (only to make things worse) to the righteous “edifications” of a religious group imposing its “order” on the “chaos” of a “savage” peoples … to the inadvertent tragedy of simply and ignorantly being in the wrong place at the wrong time (e.g., the introduction of weeds, disease, etc. by colonizing “aliens” to the detriment of the native population; e.g., smallpox, AIDs, etc.). Bradbury is my favourite author for this reason (yes, and because he makes me cry…)

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.