It was time to go back out west for me. So, I packed up my car Benny with my precious treasures—including all my plants—and drove west from Peterborough, Ontario (where I’d been living for a decade). My destination was Vancouver, BC, where my son and sister and good friends live.

I looked forward to the drive through the boreal forest of the Canadian Shield—spectacular country of mostly black spruce forest, rugged billion-year old rocks and ancient inland seas. Because I’m a limnologist and ecologist, I particularly looked forward to driving along the northern shores of Lake Superior. Distinguished by iconic terraced cobble shores, vast sand beaches, steep gnarly cliffs and brooding headlands, Lake Superior was certain to be a highlight of my trip. I anticipated experiencing this Great Lake with the giddy excitement of a child.

Water-carved sandstone and granite / rhyolite boulders form shore of Stone Beach, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

I got my first glimpses of this massive lake at Sault Saint Marie, a charming town on the southeastern shore of Lake Superior and the location of the lake’s outlet, St. Marys River. My first stop for a more immersive experience of the lake was Batchawana Bay, part of Pancake Bay Provincial Park, where I explored the mostly sand coast and shore forest. I’m told that the name Batchawana comes from the Ojibwe word Badjiwanung that means “water that bubbles up”, referring to the bubbling current at Sand Point.

.

.

Batchewana Bay is not only a main access point to several trails of the Lake Superior Water Trail; it also serves as a popular place for boaters and kayak paddlers to launch their craft for water adventure. The cold water and high wind fetch often make for treacherous boating. The Lake Superior Watershed Conservancy put up a sign at Batchewana Bay warning paddlers about dangerous and wily currents, including rip currents and channel currents and effects of offshore winds, accompanied by sudden surges.

.

.

From Batchawana Bay, I continued north along the lake’s eastern shore, past Chippewa Falls, formed on 2.7 billion year old pink granite bedrock, covered by a later basalt flow; here, the Harmony River tumbles some 6 metres before emptying into Lake Superior.

I found access points including Stone Beach, Alona Bay, Agawa Bay, and Katherine Bay, variously dominated by pebbled shores with rocky granite outcrops and finely sculpted sandstone—all overseen by windswept pine, cedar and spruce. This part of the lake lies in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest area, dominated by mixed forest of fir, spruce, cedar and paper birch.

.

.

Along the cobble shores of Alona Bay, I met a trio of rock hounds, looking for distinct Lake Superior agate, quite fetchy with its rich red, orange and yellow colours. I was told that the colours are caused by the oxidation of iron that leached from rocks. Fascinated by their varied colours and rounded shapes, I fell into a hypnotic meditation, picking up pebbles, rubbing them wet to reveal their bright colours and examining them close up.

Local rock hounds collecting choice pebbles at Alona Bay, Lake Superior (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

On the pink granite in Alona Bay, I found some brilliant lichen, which I confirmed was Elegant Starburst Lichen (Rusavskia elegans formerly Xanthoria elagans)—documented by other lichenologists as common on Lake Superior’s granite shores. I also saw patches of Rock Disk Lichen (Lecidella stigmatea).

.

.

Agawa Bay and surrounding high points provide magnificent views of the Lake Superior shoreline and surrounding country. The high rising hills are easily one of the most rugged and beautiful in Ontario. The area is underlain mostly by over two billion year old granitic rocks of igneous origin that form part of a large batholitic mass formed in the Algoman period of Precambrian time.

.

.

It’s a short hike (0.8 km) through the woods on a trail that leads to the Agawa Rock Pictographs, an amazing collection of Aboriginal pictographs that sends one’s senses soaring with imagination. Beautiful representations of real and mythical animals fill the granite canvas;, one is Mishipeshu, the Great Lynx. This mythical creature is a water dwelling dragon-like animal that also resembles a lynx with horns and a back tail covered in scales. Mishipeshu is believed to cause rough and dangerous water conditions claiming numerous victims.

.

.

The trail it itself a highlight, takes you up a steep rock-hewn staircase, with steep cliff faces looming overhead, and along rocky pathways. The pictographs are viewed from a rock ledge below the 15-story high cliff that faces Lake Superior.

.

.

My second night stop was Wawa, on the edge of the boreal forest of the Canadian Shield, known for its giant ugly goose sculptures. The name Wawa comes from the Ojibwe word wewe for “wild goose.” The town, which resembles a modern-day version of an old pioneer town included the colourful Young’s General Store, where you could purchase anything from moccasins and fishing tackle to homemade fudge and ice cream.

.

.

From Wawa, I drove west along the most northerly shores of Lake Superior, stopping at access points including Schreiber Beach, Cavers and Rossport. I found this stretch of Lake Superior’s northern coast from Terrace Bay to Nipigon particularly enchanting. Here I found several access points off the road that drew me like Alice into wondrous boreal landscapes, offering windows to an ancient time before humans walked the earth.

Near Schreiber, I stopped on the road to explore deep pink smooth granite outcrops covered in foliose Cumberland Rock Shield Lichen (Xanthoparmelia cumberlandia) and cushions of fruticose Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia spp.) where shallow soil pockets had grown.

.

The Lake Superior shoreline at Rossport consists mostly of exposed primordial granite, worn smooth by wave action. The granite here is mostly pink feldspar, quartz, and black mica. According to E.G. Pye, this rock is called porphyritic granite, an igneous rock that crystalized from a natural melt, or magma.

.

Transition Zone & the Disjunct Plants of Lake Superior’s Northern Coastline

.

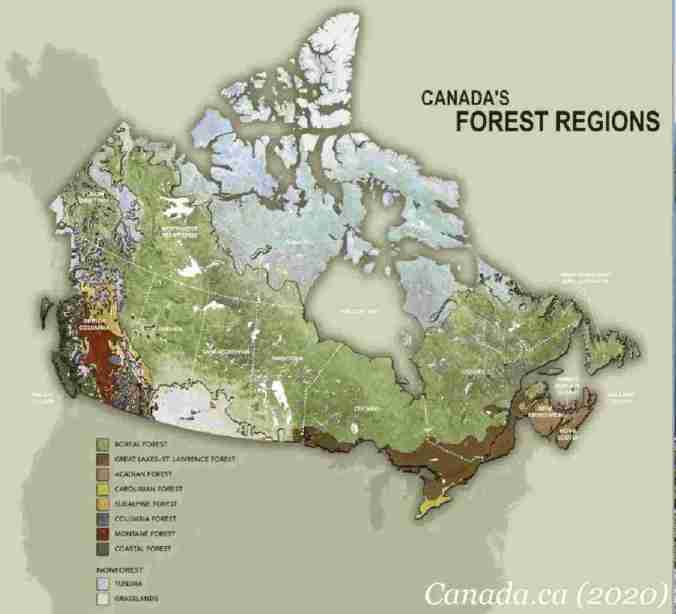

Though it lies in the boreal forest (typified by black spruce), the northern shoreline of Lake Superior in fact also supports species more characteristic of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest (e.g. white spruce, white cedar, red maple, paper birch). The northern shoreline of Lake Superior is therefore considered a transition zone between these two types of forest ecosystems.

.

.

Nestled in the rocky cracks and crevices of Lake Superior’s wild rocky shores, I discovered several cold-loving plants that normally grow in high alpine areas of the Arctic. Botanists refer to them as “Arctic-alpine disjunct plants,” separated from their usual arctic-alpine habitat and regarded as possible relicts of the last glaciation. Typically, such plants grow much farther north; but these plants have adapted to the unique cold micro-environment of Lake Superior’s northern shores. Examples include encrusted saxifrage (Saxifraga paniculata), black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), arctic fir clubmoss (Huperzia selago), elegant groundsel (Packera indecora), and the carnivorous English sundew (Drosera anglica).

.

Lichens of Lake Superior’s Northern Coastline

.

I met old friends on the lake’s wild shores, lichens that made their homes on the water-smoothed rock surfaces and gnarly rock cliffs and boulders. Random patches of the crustose Yellow Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum), rosettes of the foliose Cumberland Rock Shield Lichen (Xanthoparmelia cumberlandia) and Tile Lichen (Lecidea sp.)—all lichens I’d encountered on my studied Catch Rock, a granite outcrop in the Catchacoma old-growth hemlock forest near Gooderham.

.

.

Circular patches of bright tangerine-orange Elegant Starburst Lichen (Rusavskia elegans formerly Xanthoria elegans) graced many of the rocky surfaces. I particularly noted them on the exposed granite slabs of Schreiber Beach and Rossport, often accompanied by Peppered Rock-Shield Lichen (Xanthoparmelia conspersa) and grey Cinder Lichen (Aspicillia cinerea).

.

.

William Purvis writes that R. elegans is a nitrophile (nitrogen lover) and is common at sites that are regularly fertilized by birds. In other words, they like bird poop. Inuit hunters knew that orange lichen meant small mammals like marmots probably lived nearby (the poop connection again). The orange colour comes from the carotenoid pigment, which acts like sunscreen to protect the lichen from UV radiation. This was the lichen that made it into space in 2005, exposed to the extremes of space (e.g. temperature, radiation and vacuum) for 1.5 years. Most of the samples continued to photosynthesize when they returned to Earth.

.

.

Limnology & Geology of Lake Superior & Watershed

.

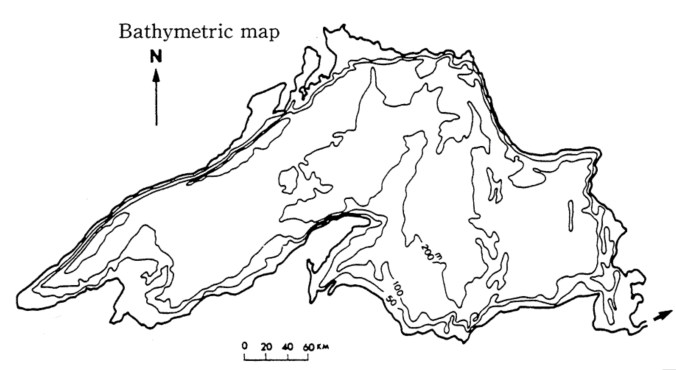

Lake History

Lake Superior was formed 10,000 years ago when glacial melt-water filled a billion-year-old volcanic basin. The lake is the size of Austria, covering an area of about 82,100 km3 and making it the largest lake in the world by surface area. Lake Superior holds 10% of the Earth’s surface freshwater—enough to fill the other Great Lakes plus three more Lake Eries, making it the third largest lake in the world by volume. The Ojibwe call the lake gichi-gami (great sea), which so aptly describes this inland sea.

Slabs of granite rocks scatter along the shore of Lake Superior near Rossport, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

For a comprehensive summary of Lake Superior’s geologic history and rock formations see E.G. Pye’s 1969 guidebook “Geology and Scenery: North Shore of Lake Superior.”

.

Lake Characteristics

Lake Superior is considered an oligotrophic lake of low productivity, characterized by cold, deep, nutrient-poor nutrients (particularly phosphorus and nitrogen). Its mean depth is 147 meters with a maximum depth of 406 meters. Fed by 200 rivers, Lake Superior holds 12,100 km3 of freshwater—enough to cover the entire North and South American continents with 30 cm of water. The lake’s volume is sufficiently large that it takes almost two centuries for a drop of water to circulate the lake before leaving through St. Marys River—its only natural outflow at Sault Ste. Marie—which flows into Lake Huron. Lake Superior also experiences seasonal circulation; the lake stratifies into two major temperature layers in summer and winter and undergoes mixing (turnover) twice in spring and fall, making it a dimictic lake.

.

Because of lack of plankton and turbidity from silt (due to cold waters low in nutrients), the lake is super clear with Secchi disk depths of 20-23 meters observed. Samuel Eddy at the University of Minnesota provided a summary of zooplankton and phytoplankton in the lake.

.

Macrophytes appeared nonexistent on the wave-washed shallows, though some boulders were covered in periphyton (e.g. attached algae, mostly diatoms). I also noticed some filamentous algae on the shore rocks near Rossport, likely Cladophora and Spirogyra, known to occur in the sheltered waters of the lake.

Granite shore near Rossport with green filamentous algae (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

Lake Fetch & Seiches

.

Because of its size, Lake Superior provides long distances for wind to push water from one end to the other; these distances, called fetches, can exceed 500 km on Lake Superior. As a result, the lake experiences ‘tides’ called seiches—essentially oscillations in water level caused by strong winds and changes in atmospheric pressure. This causes a sloshing effect across the lake (of about a metre), much like a cup of coffee as it’s being carried, and exposes shorelines to dramatic fluctuations in shoreline levels with large waves, which can be as high as 6 m during storms.

.

Lake Geology

.

The rocks of the lake’s northern shore date back to the early history of the earth, during the Precambrian Era (4.5 billion to 540 million years ago) when magma forcing its way to the surface created the intrusive granites of the Canadian Shield. With a watershed rich in minerals such as copper, iron, silver, gold and nickel, the lake lies in long-extinct Mesoproterozoic rift valley (Midcontinent Rift). Over time eroding mountains deposited layers of sediments that compacted to become limestone, dolomite, taconite and shale. As magma injected between layers of sedimentary rock, forming diabase sills, flat-topped mesa formed (particularly in the Thunder Bay area), where amethyst formed in some cavities of the rift. Lava eruptions also formed black basalt, near Michipichoten Island.

.

During the Wisconsin glaciation 10,000 years ago, ice as high as 2 km covered the region; the ice sheet advance and retreat left gravel, sand, clay and boulder deposits as glacial meltwater gathered in the Superior basin

Although the lake currently freezes over completely every two decades, scientists speculate that by 2040 Lake Superior may remain ice-free due to climate change. Warmer temperatures may also lead to more snow along the shores of the lake.

Rock-strewn Katherine Bay, Lake Superior, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

| Lake Superior & Watershed Characteristics | |

| Parameter | Value |

| Age | 10,000 years |

| Trophic Status | Oligotrophic |

| Visibility (Secchi Depth) | 8-30 m |

| Thermal Stratification | dimictic |

| Length | 563 km |

| Breadth | 257 km |

| Mean Depth | 147 m |

| Maximum Depth | 406 m |

| Volume | 12,100 km3 |

| Lake Surface Area | 82,100 km2 |

| Watershed Area | 127,700 km2 |

| Shoreline Length | 4,385 km |

| Water Residence / Flushing Rate | 191 years |

| Fetch | 500 km |

| Outlet | St Marys River |

.

.

References:

Brandt et. al. 2015. “Viability of the lichen Xanthoria elegans and its symbionts after 18 months of space exposure and simulated Mars conditions on the ISS.” International Journal of Astrobiology.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. 112pp.

.

.

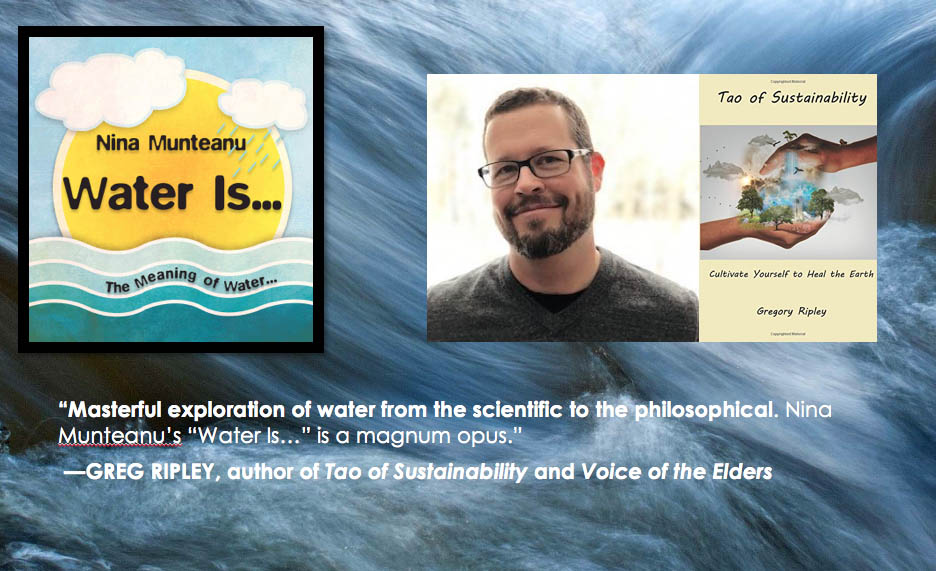

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.