I rock on the cedar swing on my veranda and hear the wind rustling through the gaunt forest. An abandoned nest, the forest sighs in low ponderous notes. It sighs of a gentler time. A time when birds filled it with song. A time when large and small creatures — unconcerned with the distant thrum and roar of diggers and logging trucks — roamed the thick second-growth forest. The discord was still too far away to bother the wildlife. But their killer lurked far closer in deadly silence. And it caught the birds in the bliss of ignorance. The human-made scourge came like a thief in the night and quietly strangled all the birds in the name of progress.

excerpt from “Robin’s Last Song” by Nina Munteanu

My short story Robin’s Last Song was republished recently in the superlative online magazine Metastellar. The story was first published in 2021 in Issue 128 of Apex Magazine and an earlier version of the story called Out of the Silence appeared in the literary magazine subTerrain Magazine Issue 85 in 2020.

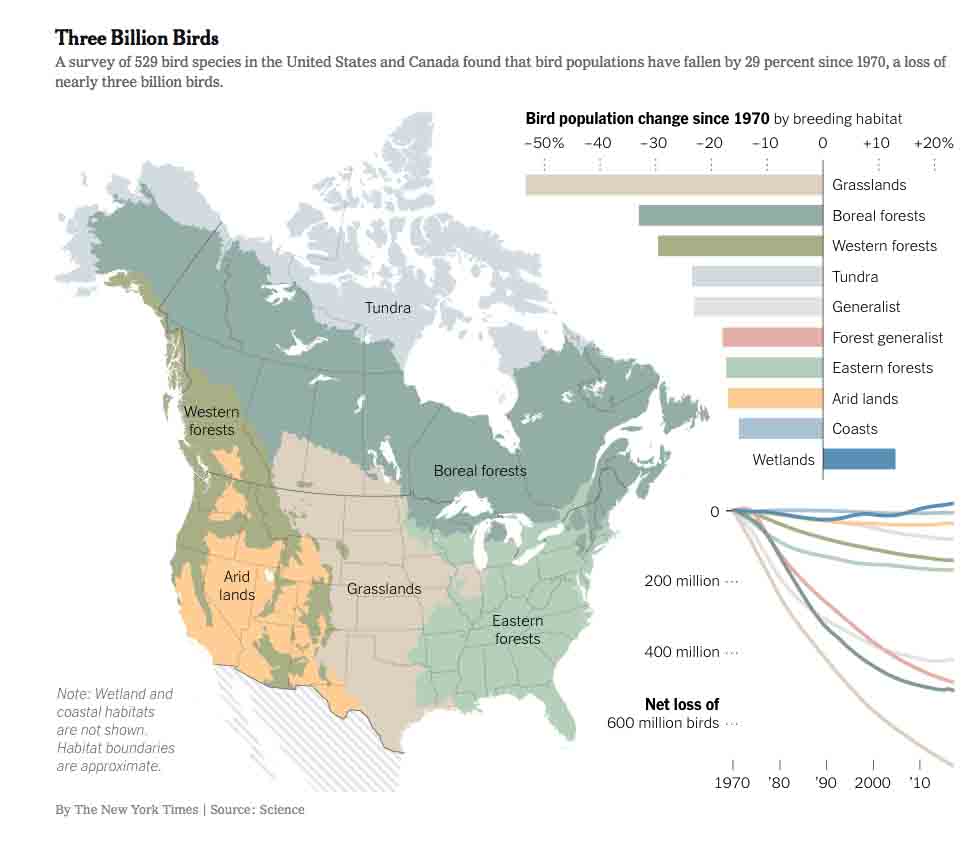

I raced up the stairs to the auditorium then quieted my breath and listened at the door, heart thumping like a bird trying to escape. Professor Gopnik was ten minutes into his lecture; I could hear his commanding voice: “… estimates that the entire number of birds have been reduced by a third in five decades—I mean common birds like the robins, sparrows, warblers, and even starlings…”

Excerpt from “Robin’s Last Song” by Nina Munteanu

He was talking about Rosenberg’s paper in Science. The study shocked the scientific community; but I had already observed the decline of the house sparrow around my aunt and uncle’s house near the Old Mill. And the robin—my namesake, whose song heralded spring for me—had grown quiet.

I imagined Gopnik waving the journal at the class in his typical showman style. He had a habit of wandering the stage like an evangelist, fixing each student with intense blue eyes as if challenging them to believe. I thought him an over-confident condescending prig. But for someone who looked as young as the students he was teaching, Gopnik was brilliant. And what he was doing was so important. I wanted so badly to work under him as a grad student. But he terrified me.

The Story Behind the Story

It all began with my discovery of an emerging bioacoustic tool, soundscape ecology, that measures biodiversity and ecosystem functionality. I’d just read the disturbing 2019 Science article by Rosenberg and team who determined that our slow violence of habitat degradation and toxic pollution has reduced the world’s bird population by a third in just five decades. I was devastated; I could not imagine a world without the comforting sound of birds. What would it be like if all the birds disappeared?

Already primed with research into genetic engineering for the sequel to my 2020 eco-novel, A Diary in the Age of Water, my muse (often delightfully unruly) played with notions of the potential implication of gene hacking in ecological calamity and how this might touch on our precious birds: when nature “is forced out of her natural state and squeezed and moulded;” her secrets “reveal themselves more readily under the vexations of art than when they go their own way.”

Robin’s Last Song is a realizable work of fiction in which science and technology are both instigators of disaster and purveyors of salvation. Today, gene-editing, proteomics, and DNA origami—to name just a few—promise many things from increased longevity in humans to giant disease-resistant crops. Will synthetic biology control and redesign Nature to suit hubris or serve evolution? What is our moral imperative and who are the casualties? As Francis Bacon expressed in Novum Organum, science does not make that decision. We do.

You can read an Interview on Writing Robin’s Last Song that Alberta author Simon Rose did with me recently.

I also recently sat down with Rebecca E. Treasure of Apex Magazine for a conversation about story, ecology, and the future. Here’s how it begins:

Apex Magazine: The Way of Water in Little Blue Marble is such a powerful piece touching on water scarcity and friendship, a dry future and the potential for technology to overtake natural ecology. Robin’s Last Song explores extinction, human fallibility, friendship, and again, that conflict between technology and nature. Do you think we’re heading toward the kind of dystopia shown in these stories?…

For more about bird declines around the world see my articles: “What if the Birds All Die?” and “Birds are Vanishing.”

“Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds. The early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song”

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Read my other stories in Metastellar here: Nina Munteanu in Metastellar Speculative Fiction and Beyond.

p.s. May9: I just learned that Robin’s Last Song was selected by the NYC Climate Writers Collective as part of an exhibition in the Climate Imaginarium on Governors island. The exhibition, starting May 18, will run throughout the summer of 2024.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.