Courtyard of Chateau Chillon, Switzerland (photo by Nina Munteanu)

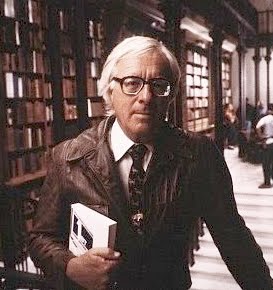

When a friend of mine asked me recently what book changed my life, I didn’t have to think too far. Two books came to mind instantly, both novels: Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury and Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy. Two very different books, genres, time periods and subject matter. Yet they held in common superlative storytelling, incredible sensuality, and stirring use of metaphor. Bradbury’s simple yet powerful prose held humanity’s most vulnerable traits at close scrutiny, stirring me with the stories of ordinary people journeying into extraordinary places. Hardy’s lyrical and evocative prose entranced me with stories of extraordinary people journeying in ordinary places.

Of course there were many other books and authors who’d influenced me greatly, but these two particularly made me want to be a writer and move people as they had moved me.

A recent discussion with one of my writing students got me thinking about the merits of reading—fiction, particularly—in the writing process and creative writing, especially.

Janice confided to me in an email that her husband prefers non-fiction and reads slowly, while her daughter reads both fiction and non-fiction voraciously and quickly.

Chillon Castle, Switzerland (photo by Nina Munteanu)

“I think (and I could be wrong),” said Janice, “but the more fiction someone reads, the better they are able to communicate in a written form.” She suggested that, “Non-fiction does not have the breadth of style that fiction has, and thus the opportunities to find a style which adequately reflects the writer is somewhat curtailed if all they read is non-fiction. Style is a very personal thing and to have to write large swaths of material, the writer has to be comfortable in writing, thus if they find their ‘voice’ the information can be communicated in a manner which the writer does not find drudgery to write and best of all the reader will not find dry and difficult to read.”

It turns out that Janice’s keen observations and conclusions are corroborated by a fair amount of recent research. In their study a study entitled “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind” in the October 2013 issue of Science, researchers Kidd and Castano reported that reading literary fiction led to better performance on tests of affective and cognitive Theory of Mind compared with reading nonfiction, popular fiction or nothing at all. Theory of Mind (ToM) describes the ability to understand others’ mental states, a crucial skill in complex social relationships that characterize human societies.

Reading Fiction Improves Empathy

Neuroscientists at Emory University, led by Professor Gregory S. Berns, published findings in the December 2013 issue of the journal Brain Connectivity that suggested that reading a novel can improve brain function on a variety of levels. Reading fiction, reported Berns et al., improved the reader’s ability to empathize with others and “flex their imagination in a way that is similar to the visualization of a muscle memory in sports,” says Christopher Bergland in a recent article in Psychology Today.

“Changes caused by reading a novel are registered in the left temporal cortex,” says Bergland. That’s an area of the brain associated with receptivity for language. It’s also the primary sensorimotor region of the brain. “Neurons of this region have been associated with tricking the mind into thinking it is doing something it is not, a phenomenon known as embodies cognition.” Bergland suggests that just thinking about playing basketball can activate the neurons associated with the physical act of playing.

The neural changes suggested that “reading a novel can transport you into the body of the protagonist,” says Berns, who is director of Emory University’s Center for Neuropolicy in Atlanta. “Stories shape our lives and in some cases help define a person,” adds Berns. “We want to understand how stories get into your brain and what they do to it.”

Nina Munteanu lectures in class

Storytelling in novels is a multi-faceted communication that engages a broad range of brain regions. I spend an entire 12-week course at George Brown College and the Universtiy of Toronto workshopping the story tools of an effective writer with my students; tools ranging from the use of metaphor to multi-layered plotting and character archetypes. Story—unlike anecdote, which many mistake for story—resonates with readers in a variety of conscious and sub-conscious ways. Neurobiological research has just begun to identify the brain networks that are activated when processing stories.

The Emory study used a 2003 thriller by Robert Harris (Pompeii), which follows a protagonist rushing against time to save the love of his life. Researchers chose the book for its page-turning plot. “It depicts true events in a fictional and dramatic way,” Bern says. “It was important to us that the book had a strong narrative line.”

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans on a group of students before and after reading a portion of the Harris novel, the Emory researchers demonstrated heightened connectivity in student’s brains. Areas of enhanced connectivity included students’ left temporal cortex, associated with language comprehension, and the central sulcus, associated with sensations and movement.

“The anterior (front) bank of the sulcus contains neurons that control movement of parts of the body,” Berns tells us. “The posterior (rear) bank contains neurons that receive sensory input from the parts of the body. Enhanced connectivity here was a surprise finding, but it implies that, perhaps, the act of reading puts the reader in the body of the protagonist.”

“The ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes through embodied cognition is key to improving theory of mind and also the ability to be compassionate,” says Bergland in his article in Psychology Today. He adds, “Although this study does not directly draw these conclusions, it seems like common sense that if we encourage our children to read—as opposed to tuning out through television—theory of mind and the ability to be compassionate to another person’s suffering will improve.”

“We already knew that good stories can put you in someone else’s shoes in a figurative sense,” says Berns. “Now we’re seeing that something may also be happening biologically.”

The Berns study concluded, “At a minimum, we can say that reading stories—especially those with strong narrative arcs—reconfigures brain networks for at least a few days. It shows how stories can stay with us. This may have profound implications for children and the role of reading in shaping their brains.”

Reading Sharpens Your Brain

In her paper What Reading Does for the Mind, Berkley professor Anne E. Cunningham tells us that those that read generally have higher GPA’s, higher intelligence, and general knowledge than those that don’t. Her study also suggested that reading improves vocabulary and helps compensate for the normally deleterious effects of aging.

Cunningham’s studies demonstrated that reading boosted analytical thinking. This includes the ability to detect patterns more quickly. When I started to read more, my vocabulary increased tremendously. It also improved my spelling. Both of these are important to writers. As psycholinguist Steven Pinker pointed out in The Sense of Style, reading the works of writers you admire is an important way to becoming a better writer. Reading improves your memory. It also helps prioritize goals, by helping us to see another perspective and think “outside” our comfortable box.

Wilson et al. reported in the July 3 2013 issue of the journal Neurology that those who engaged in mentally stimulating activities (such as reading) earlier and later on in life experienced slower memory decline compared to those who didn’t. In particular, people who exercised their minds later in life had a 32 percent lower rate of mental decline compared to their peers with average mental activity.

Reading May Help Against Alzheimer’s Disease

According to research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2001, adults who engage in hobbies that involve the brain, like reading or puzzles, are less likely to have Alzheimer’s disease, while leisure limited to TV watching may increase the risk.

“The brain is an organ just like every other organ in the body. It ages in regard to how it is used,” lead author Dr. Robert P. Friedland told USA Today. “Just as physical activity strengthens the heart, muscles and bones, intellectual activity strengthens the brain against disease.”

Reading Reduces Stress and Helps You Sleep Better

That reading reduces stress and helps you sleep better is an intuitive notion recently corroborated by research at the University of Sussex. Findings by neuropsychologists, led by Dr. David Lewis show that reading a newspaper or book works better and faster than listening to music, going for a walk or sitting down with a cup of tea to calm stressed out nerves. Reading reduced stress levels by 68 per cent. Psychologists say this is because the human mind has to concentrate on reading and the distraction eases the tensions in muscles and the heart. Lewis and his team found that subjects only needed to read, silently, for six minutes to slow down the heart rate and ease tension in the muscles.

Dr Lewis said: “Losing yourself in a book is the ultimate relaxation. “This is more than merely a distraction but an active engaging of the imagination as the words on the printed page stimulate your creativity and cause you to enter what is essentially an altered state of consciousness.”

So, here’s my question to you: what book changed your life and why?

References:

Berns Gregory S., Blaine Kristina, Prietula Michael J., and Pye Brandon E. 2013. “Short-and Long-Term Effects of a Novel on Connectivity in the Brain.” Brain Connectivity 3(6): 590-600. doi:10.1089/brain.2013.0166.

Cunningham, Anne. E. 1998. “What Reading Does for the Mind.” In: American Educator/American Federation of Teachers. Spring/Summer,1998.

Kidd, David Comer and Emmanuele Castano. 2013. “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind.” Science 342 (6156): 377-380. October 2013.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Censorship suppresses ideas and information that certain people — individuals, groups or government officials — find objectionable or dangerous. Censors pressure public institutions, like libraries, to suppress and remove from public access information they judge inappropriate or dangerous, so that no one else has the chance to read or view the material and make up their own minds about it. “Censorship … creates, in the end, the kind of society that is incapable of exercising real discretion,” said Henry Steel Commager.

Censorship suppresses ideas and information that certain people — individuals, groups or government officials — find objectionable or dangerous. Censors pressure public institutions, like libraries, to suppress and remove from public access information they judge inappropriate or dangerous, so that no one else has the chance to read or view the material and make up their own minds about it. “Censorship … creates, in the end, the kind of society that is incapable of exercising real discretion,” said Henry Steel Commager.

The writer’s date is a gift you give yourself. It’s a gift of receiving, of opening yourself to discovery, wonder, and inspiration. It is ultimately a self-nurturing activity in which you let your child-self out to play. “The imagination-at-play is at the heart of all good work,” Cameron tells us. Cameron also warns that you may find yourself avoiding artist dates. “Recognize this resistance as a fear of intimacy—self-intimacy.”

The writer’s date is a gift you give yourself. It’s a gift of receiving, of opening yourself to discovery, wonder, and inspiration. It is ultimately a self-nurturing activity in which you let your child-self out to play. “The imagination-at-play is at the heart of all good work,” Cameron tells us. Cameron also warns that you may find yourself avoiding artist dates. “Recognize this resistance as a fear of intimacy—self-intimacy.”

The knight standing in the mire is Vivianne.

The knight standing in the mire is Vivianne.

This article contains excerpted material from

This article contains excerpted material from