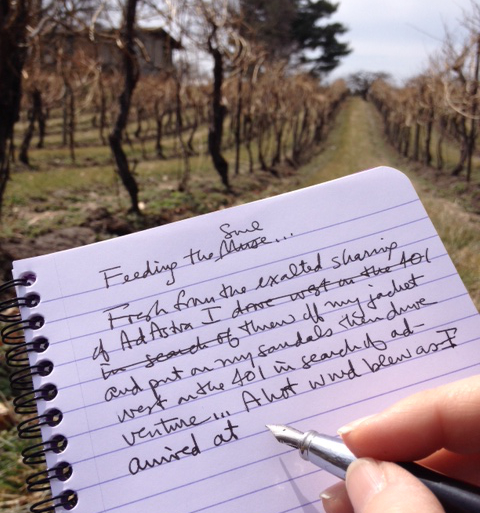

I love using the em dash. Along with the semi-colon, it’s my go-to punctuation. And before you ask—no, I don’t use AI in my writing.

Lately, I’ve discovered that use of the em dash has come under criticism by writers and discerning readers, given its apparently overwhelming use by AI. The appearance of em dashes in script is now considered a “tell” that a written work was AI-generated.

.

.

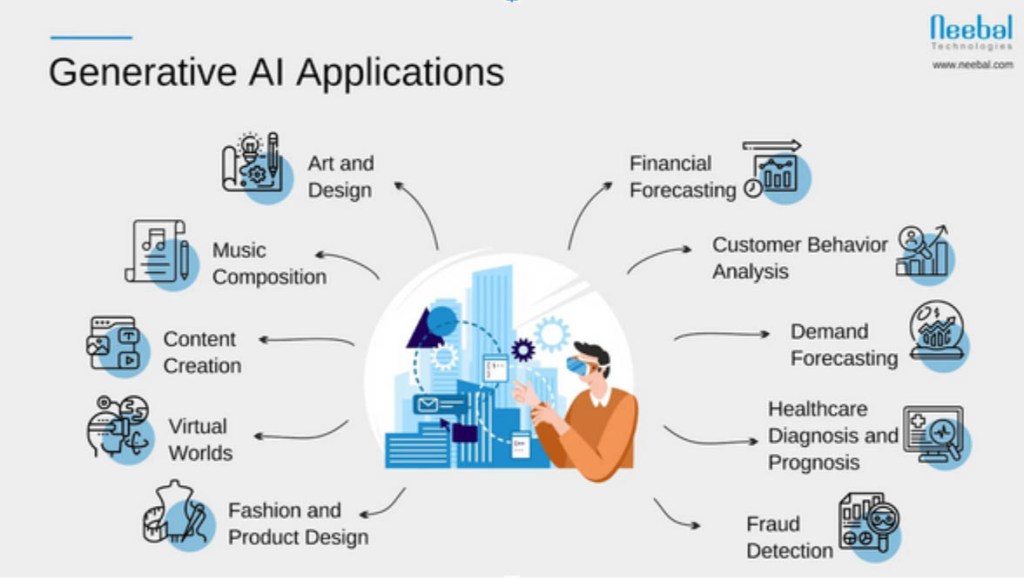

I’m told that em dashes were deeply embedded in the AI learning algorithms—they were everywhere in human-generated training data such as books, articles, essays because we used them so often. Because they weren’t flagged as risky during training, they became a default. AI learns through pattern mimicry by sifting through massive text datasets (that have included my own works of fiction and non-fiction;by the way, I use the em dash a lot because I love what it does for a sentence). One theory suggests that em dashes are preferred by autoregressive models for waving tokens or providing structural breaks. Its use has its own name: the “ChatGPT hyphen.” The discussion alone has brought more attention to the em dash, mostly negative attention.

As a result of em dash’s association with LLM-generated text, some writers have started avoiding the use of em dashes altogether to prevent their work from being labelled fake—despite its legitimate appearance in human writing for centuries.

This is a real shame.

Because, the em dash is a visual and versatile tool to achieve an emphasized pause, the equivalent to a raised eyebrow, a dramatic mid-sentence shift in thought, or a noteworthy point to consider. Used correctly and with intention, the em dash provides depth, contextual complexity and three dimensionality within an otherwise unidirectional sentence. The em dash singles out a thought, raises it above the script to show its merit amid the greater sentence concept. What is often achieved is more complex and layered with additional meaning and clarity. The visual nature of the em dash—how it looks in a sentence—is also important. Because, as writer Bill Zinsser says, “Writing is visual—it catches the eye before it has a chance to catch the brain.” There’s a kind of aesthetic nature to how writing sits on a page; this is also why paragraphing—breaking up long text into shorter paragraphs on a page—is so important. The white space created by these breaks subliminally signals the reader, giving them a chance to breathe as they read. The presence of an em dash similarly signals the reader to read the enclosed phrase apart—yet remaining an important part—of the sentence.

Here’s how The Chicago Manual of Style explains it:

“The em dash has several uses. It allows, in a manner similar to parentheses, an additional thought to be added within a sentence by sort of breaking away from that sentence—as I’ve done here. Its use or misuse for this purpose is a matter of taste, and subject to the effect on the writer’s or reader’s “ear.” Em dashes also substitute for something missing. For example, in a bibliographic list, rather than repeating the same author over and over again, three consecutive em dashes (also known as a 3-em dash) stand in for the author’s name. In interrupted speech, one or two em dashes may be used: “I wasn’t trying to imply—” “Then just what were you trying to do?””

After announcing that the em dash is their favourite punctuation, Bavesh Rajaraman listed the several ways you can use this punctuation:

1. use it like how I regularly do, with bridging sentences, kind of like a longer comma, or a semicolon.

2. use it like a colon: “Some examples of transition metal atoms are — Co, Ni, Fe”

3. use it like a parenthesis, to add extra detail, or clarify. “The Wheel of Time has been an incredibly strong fantasy series — till book 6 where I’m currently at — with size and scope incomparable to its contemporaries”

4. use it to interrupt a speaker: “Melissa, I’m gonna be leaving for work, make sure to keep the door — “ as Klein heard the door thud, “I guess she understood the assignment,” he lampooned as he headed for work.

5. use it as something more important than demarcated in parenthesis. Here’s a snippet from Brandon Sanderson’s Essay “Outside”: “When you’re very young, it’s proximity — not shared interests — that makes friends. This often changes as you age. By fourteen, John had found his way to basketball, parties, and popularity. I had not.”— Brandon Sanderson, 2023

Celebrated poets and writers—including Emily Dickinson, Henry James, Virginia Woolf, and Stephen King—have used the em dash for emphasis, as bridge or interruption, or to set off parenthetical thoughts, create unique rhythms and cadence in their writing. The poet Emily Dickinson was known to use dashes instead of commas or periods to create pauses, express emotion and link ideas in her poetry. These celebrated authors used the em dash for emphasis and interruption, drawing attention to a phrase or to intentionally break a sentence’s flow. They used the em dash as appositives, to set off additional information with more impact. They used the em dash to create rhythm and pacing. They used the em dash to create a unique voice and style. The em dash is an uber-punctuation! And it’s been around since the early 1800s, adding style, pizazz, rhythm and depth to all types of writing.

I wish I had this quote from Rajaraman when I was submitting my fiction to editors, who seemed to like to remove most of my em dashes and replace them with boring commas:

“The em dash is a fiction writer’s spell-casting focus, it’s their ultimate pacing tool; used to fix the flow of a sentence. There’s no such thing as too many em dashes in literature.”

Canadian journalist Clive Thompson wrote, “Writers worry they overuse it. They shouldn’t—it’s awesome.”

All to say forget the internet conspiracy theories that em dashes are a telltale sign of AI writing; forget that ChatGPT can’t stop using them even when users tell it to stop. The em dash is not a sign of AI, but that AI was trained on good writing—good human writing. FVR at WellVersed.com adds that it’s “not a robot glitch—it’s a writer’s signature.”

So, I for one, will continue using the em dash liberally, as I have for the past forty years—long before ChatGPT hiccupped into our writing lives and long after.

.

.

References:

Csutoras, Brent. 2025. “The Em Dash Dilemma: How a Punctuation Mark Became AI’s Stubborn Signature.” Medium, April 29, 2025.

Rajaraman, Bavesh. 2025. “An Era to its Knee: An Em-dash Retrospective.” The Jabber Junction, July 29, 2025.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning novelist and short story writer of eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy. She also has three writing guides out: The Fiction Writer; The Journal Writer; and The Ecology of Writing and teaches fiction writing and technical writing at university and online. Check the Publications page on this site for a summary of what she has out there. Nina teaches writing at the University of Toronto and has been coaching fiction and non-fiction authors for over 20 years. You can find Nina’s short podcasts on writing on YouTube. Check out this site for more author advice from how to write a synopsis to finding your muse and the art and science of writing.

.