Steven Soderbergh’s stylish psychological thriller, released November 2002 in the United States by 20th Century Fox, eloquently captures the theme of Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 book. Written almost fifty years ago, Solaris is an intelligent, introspective drama of great depth and imagination that meditates on humanity’s place in the universe and the mystery of God. Soderbergh’s Solaris is a poem to Lem’s prose. Both explore the universe around us and the universe within. Not particularly palatable to North America’s multiplex crowd, eager for easily accessed answers, Solaris will appeal more to those with a more esoteric appreciation for art.

When I recently saw the 2002 20th Century Fox remake of Solaris, I was blissfully unaware of its legendary history. I say blissfully because I harbored no pre-conceived notions or expectations and therefore I was struck like a child viewing the Northern Lights for the first time. The stylish, evocative and dream-like imagery flowed to a surrealistic soundtrack by Cliff Martinez like the colors of a Salvador Dali painting. It was only later that I discovered that Russian experimental director, Andrei Tarkovsky, had previously filmed Solaris in 1972 based on Lem’s masterful 1961 book of the same name. Reprinted by Harcourt, Inc. with a new cover featuring a sensual image from the 2002 film, the original book was translated in 1970 from the French version by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox for Faber and Faber Ltd.

Written almost fifty years ago, Solaris is a dark psychological drama. Soderbergh faithfully captures the intellectual yet sensual essence of Lem’s book by tempering the language and movements. Featuring a fluid and haunting soundtrack, his film flows like a choreographed ballet. There is a dream-like quality to it that is enhanced by creative use of camera angles, unusual lighting, tones and contrast, and sparse language. Solarisis not an action film (no one gets shot, at least not on stage), yet the tension surges and builds to its irrevocable conclusion from frame to frame like a slow motion Tai Chi form.

In response to his friend’s plea, a depressed psychologist with the ironic name of Kris Kelvin (played with quiet depth by George Clooney), sets out on a mission to bring home the dysfunctional crew of a research space station orbiting the distant planet, Solaris. Kelvin arrives at the space station, Prometheus, to find his friend, Gibarian, dead by suicide and a paranoid and disturbed crew obviously withholding a terrible secret from him. It is not long before he learns the secret first-hand: some unknown power (apparently the planet itself) taps into his mind and produces a solid corporeal version of his tortured longing: his beloved wife, Rheya (played sensitively by Natascha McElhone) who years ago had committed suicide herself. Faced with a solid reminder, Kelvin yearns to reconcile with his guilt in his wife’s death and struggles to understand the alien force manifested in the form of his wife. He learns that the other crew are equally influenced by Solaris and have been grappling, each in their own way, with their “demons,” psychologically trapping them there.

Ironically, our hero’s epic journey of great distance has only led him back to himself. The alien force defies Kelvin’s efforts to understand its motives; whether it is benign, hostile, or even sentient. Kelvin has no common frame of reference to judge and therefore to react. This leaves him with what he thinks he does understand: that Rheya is a product of his own mind, his memories of her, and therefore a mirror of his deepest guilt—but perhaps also an opportunity to redeem himself.

Lem packs each page of his slim 204 page book with a wealth of intellectual introspection. Through first person narrative, he intimately unveils the complicated influence of this arcane force on Kelvin. Lem explains it this way: “I wanted to create a vision of a human encounter with something that certainly exists, in a mighty manner perhaps, but cannot be reduced to human concepts, ideas or images.” (Author’s Website.) Such an incomprehensible entity would serve as a giant mirror for our own motives, yearnings and versions of reality. For me the contrast presented by such an arcane alien force emphatically—but also ironically—defines what it is to be human. It is only when faced with what we are not that we discover what we are. Later in the book, Kelvin cynically observes: “Man has gone out to explore other worlds and other civilizations without having explored his own labyrinth of dark passages and secret chambers, and without finding what lies behind doorways that he himself has sealed.” In the film Gibarian sadly proclaims of the Solaris mission: “We don’t want other worlds—we want mirrors.” In the book, Lem has Snow deliver a similar message, but neither Gibarian or Snow realize that these two desires may be one and the same.

Lem’s existentialist leaning is provided throughout the book and even alluded to in the name he chose for the space station: Prometheus. In Greek mythology, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humankind for which Zeus chained him to a rock and sent an eagle to eat his liver (which grew back daily). It is interesting that Soderbergh chose to send Prometheus to a fiery crash and named Kelvin’s dead wife, Rheya, after the Greek goddess, mother of Zeus and all Olympian gods. In a late passage of Lem’s book, a devastated and sorrowful Kelvin formulates a personal theory of an imperfect god, “a god who has created clocks, but not the time they measure … a god whose passion is not a redemption, who saves nothing, fulfills no purpose—a god who simply is.”

Soderbergh addresses Lem’s existential vision with several brief but pivotal scenes. One occurs when Kelvin’s dead friend, Gibarian, returns to him in a dream on Prometheus and responds to Kelvin’s question, “What does Solaris want?” with: “Why do you think it has to want something?” Another scene occurs as a flashback to a dinner on Earth, when the real Rheya, prior to her suicide, argues with both Gibarian and her own husband about the existence of an all-knowing purposeful God, which both men argue is a myth made up by humankind: to Kelvin’s suggestion that “the whole idea of God was dreamed up by man,” Rheya insists that she’s “talking about a higher form of intelligence,” to which Gibarian cuts in with: “No, you’re talking about a man in a white beard again. You are ascribing human characteristics to something that isn’t.” Kelvin fuels it with: “We’re a mathematical probability,” which prompts Rheya’s challenge: “How do you explain that out of the billions of creatures on this planet we’re the only ones conscious of our immortality?” Neither man has an answer. Gibarian later commits suicide on Solaris rather than deal with the manifestation of his conscience. And I can’t help but wonder if the underlying reason for his inability to reconcile with his “demon” is because he was unequipped to, given his nihilistic beliefs.

Gibarian also tells Kelvin (and we must remember that all this is Kelvin really saying this to himself through his memory of the character): “There are no answers, only choices.” It is interesting then that the first pivotal choice in the story is made by the Doppelganger Rheya (also a manifestation of Solaris but a mirror of Kelvin’s own mind) and it is a choice made out of love: to be annihilated, rather then serve as an instrument of this unknown alien power to study the man she loves.

Some critics have called Soderbergh’s Solaris pretentious, boring and devoid of action and intimacy. I strongly disagree. It is simply that, as with Lem’s original story, Soderbergh’s Solaris does not surrender its messages easily. The viewer, as with the reader, must intuitively feel his or her way through the fluid poetry, free to interpret and ponder the questions. This is what I think good art should do. And I feel both the original book and Soderbergh’s movie do this with enthralling brilliance.

Where Soderbergh and Lem depart lies more in each artist’s personal vision and belief. Soderbergh seems to view the forces that drive our universe as the manifestation of an arcane motive more readily known through spirituality, perceived by the heart, and existing as a matter of belief. Lem, however, suggests that these forces are random and without purpose, defined by science, and perceived by the mind. Still, Lem is not proclaiming a nihilism of his own: he believes we are defined by the questions we ask and Lem asks a great deal of questions—leaving the reader to do the answering.

Reviewer Rick Kisonak asserted that Lem’s “novel is an icy meditation on man’s place in the universe and the mystery of God. It poses countless metaphysical questions and makes a point of answering none of them. In Soderbergh’s hands, however, Solaris becomes a celebration of romantic love, which culminates in the revelation of a caring, forgiving creator. At the end of his book, Lem writes [Kelvin ponders]: ‘the age-old faith of lovers and poets in the power of love, stronger than death, that finis vitae sed non amoris [life ends but not love] is a lie, useless and not even funny.’ The director ignores the author in favor of just such a poet” (Film Threat, [Online]). Kisonak is referring here to Rheya’s interest in Dylan Thomas and its reference throughout the movie. Another reviewer, Dennis Morton, goes so far as to suggest that the screenplay of Solaris is the first stanza of the poem, which ends with: “…though lovers be lost love shall not; And death shall have no dominion” (Santa Cruise Sentinel, [Archived online])

While I agree with some of Kisonak’s reasoning, I think he has missed the point of Lem’s book. If one continues to read from the passage Kisonak quoted above—as Kris Kelvin transcends from what he “thinks” in his intellect to what he feels and “knows” in his heart, to accept his (and humanity’s) destiny with humble fatalism—we learn that Lem ends his book in much the same way as Soderbergh’s movie: life ends but not love. The endings are physically different, in keeping with some radical alterations from the book in the movie’s setting (e.g., the original Solaris station is located on the planet and Lem assiduously describes Kelvin’s observations and interactions with the alien ocean; whereas Soderbergh’s crew virtually never leave orbit and the planet remains aloof in the background, reflecting Soderbergh’s focus). Yet, Kris makes the same choice in faith and love in both book and movie (although the choices play out differently). In matters of faith and love, here is what Kris has to say in the book: “Must I go on living here then, among the objects we both had touched, in the air she had breathed? … In the hope of her return? I hoped for nothing. And yet I lived in expectation … I did not know what achievements, what mockery, even what tortures still awaited me. I knew nothing, and I persisted in the faith that the time of cruel miracles was not past.” In the end of both movie and book, Kris Kelvin lets go of his fears and lets his spirit rise in wonder at what astonishing things Solaris (and the universe) will offer next.

In the final analysis, both book and movie are incredibly valuable but for different reasons. Soderbergh paints an impressionistic poem, using Kafkaesque brushstrokes on a simpler canvas, to Lem’s complex tapestry of multi-level prose. Lem challenges us far more by refusing to impose his personal views, where Soderbergh lets us glimpse his hopeful vision. I think that both, though, come to the same conclusion about the ethereal, mysterious and eternal nature of love. On the one hand, love may connect us within a fractal autopoietic network to the infinity of the inner and outer universe, uniting us with God and His purpose in a collaboration of faith. On the other hand, love may empower us to accept our place in a vast unknowable and amoral universe to form an island of hope in a purposeless sea of indifference. Whether love mends our souls to the fabric of our destiny; enslaves us on an impossible journey of desperate yearning; or seizes us in a strangling embrace of unspeakable terror at what lurks within—surely, then, love is God, in all its possible manifestations. This is unquestionably the message that unifies book and movie. And it is one worth proclaiming.

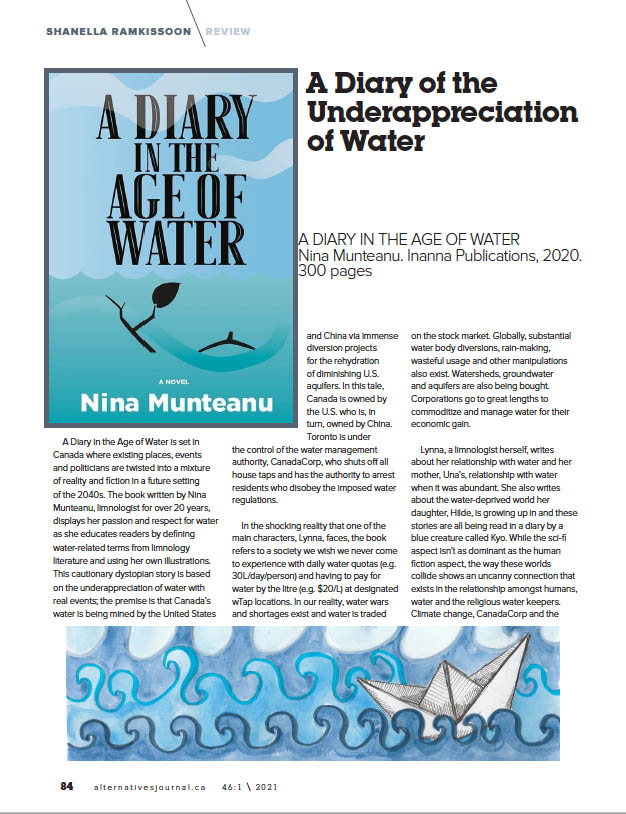

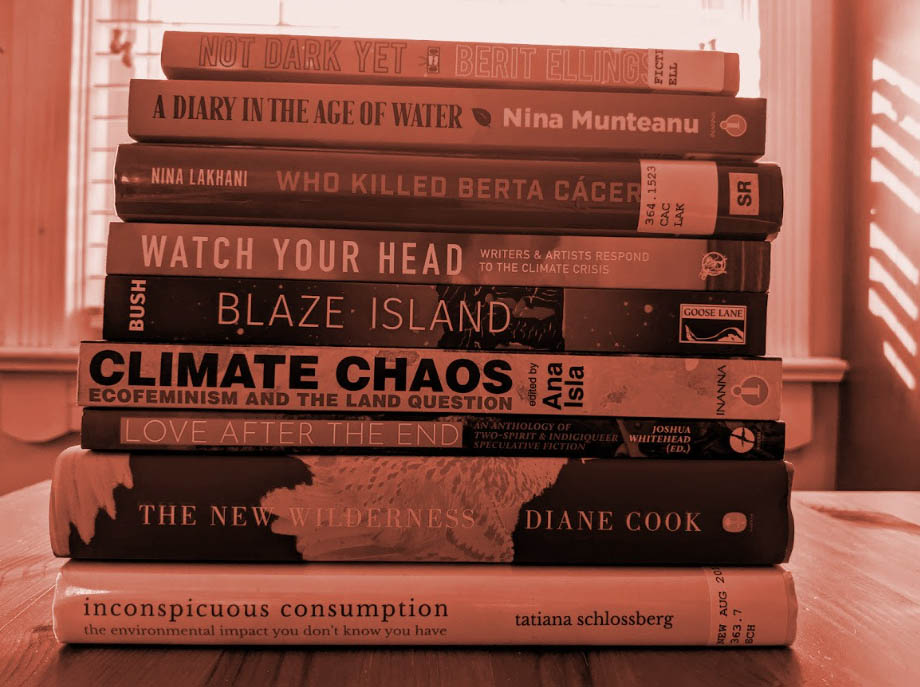

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.