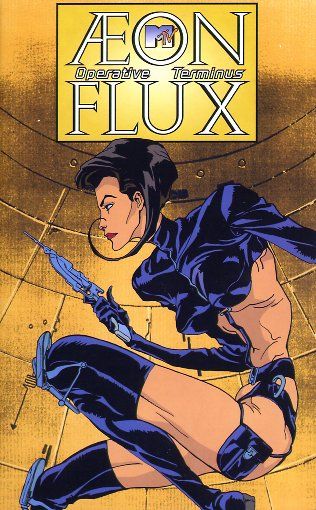

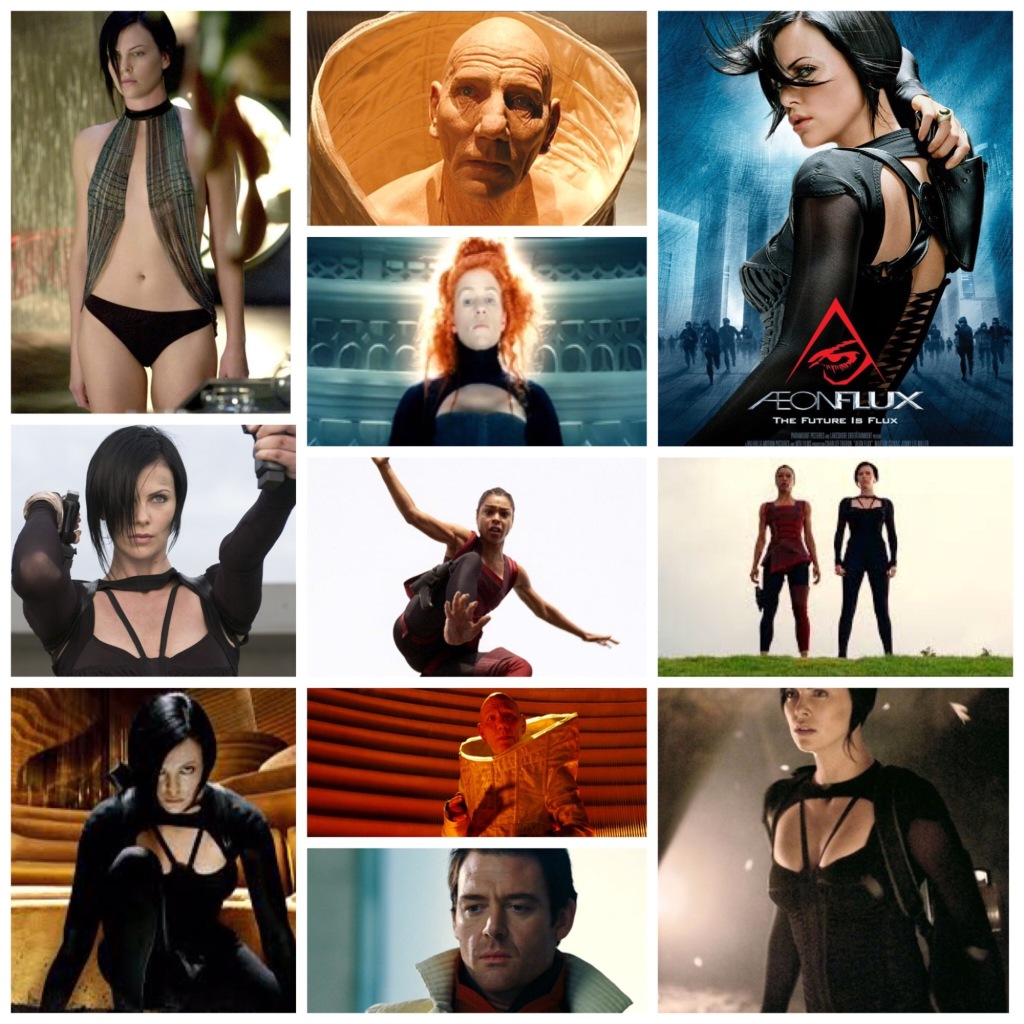

When I was first tantalized by the high-speed head-smashing trailor for the Paramount motion picture, Aeon Flux, directed by Karyn Kusama (Girlfight) and released in late 2005 (now on DVD), I was blissfully unaware of its history: that it was based on the darkly irreverant and raunchy 1995 MTV Liquid Television animated SF series created by Korean American animator, Peter Chung. The series achieved cult status among a select audience of imsoniacs (it played at midnight on MTV, if that tells you anything). This may have worked in my favour. I had no expectations or preconceptions, except for a hair-flying ride. As a result, when the content (written by Matt Manfredi and Phil Hay) had merit as social commentary, I counted it as a bonus. But, then there was the matter of the reviews that emerged between the trailors airing and my seeing the film.

Unfortunately for the motion picture, Paramount’s lack of press-screenings (and subsequent press reaction because of those lack of screenings) may have predisposed critics to dislike it. And many provided negative, though conflicting, reviews; as if they couldn’t all agree on why they didn’t like the film. Kieth Breese (Filmcritic.com) found the film “gorgeously surreal and vacuously arty.” According to Jami Bernard (New York Daily News), “in the dystopian future [of Aeon Flux], apparently, women will be bendable Barbies in leather scanties, and everyone will speak like brain-dead robots…a silly live-action movie.” Justin Chung (Variety.com) decided that Aeon Flux portrayed “the future [as] alternatively grim and hysterical…a spectacularly silly sci-fier.” A.O. Scott of the New York Times said that Aeon Flux was “flooded with colors and chilly effects [but was] drained of emotional interest, to say nothing of narrative coherence.” And, finally, William Arnold of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer called it “too somber and cerebral for the young action crowd.” Silly or too cerebral? In truth, this disappointment is because the Aeon Flux movie was wrongly perceived (and wrongly marketed) as an action thriller; it is more aptly described as a dystopian political thriller—not the brazen cry of V for Vendetta—but a subtle cautionary tale of the consequences of complacency, greed and living in absence of—and trying to cheat—nature.

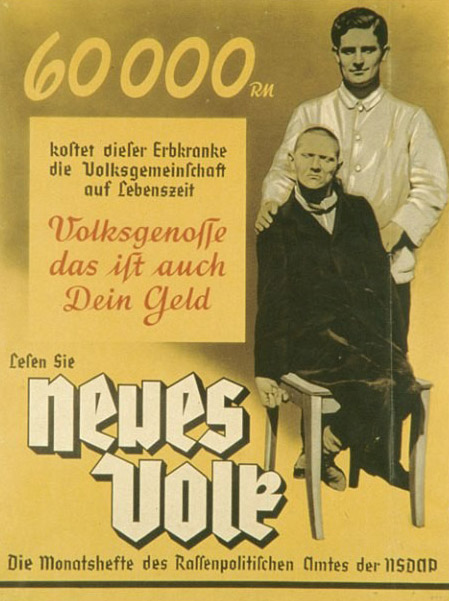

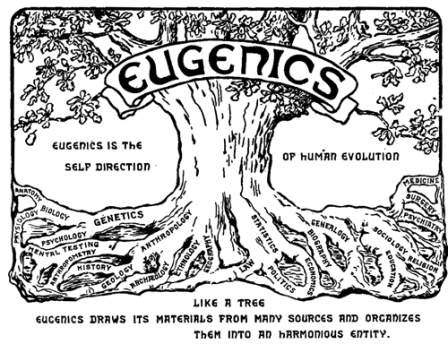

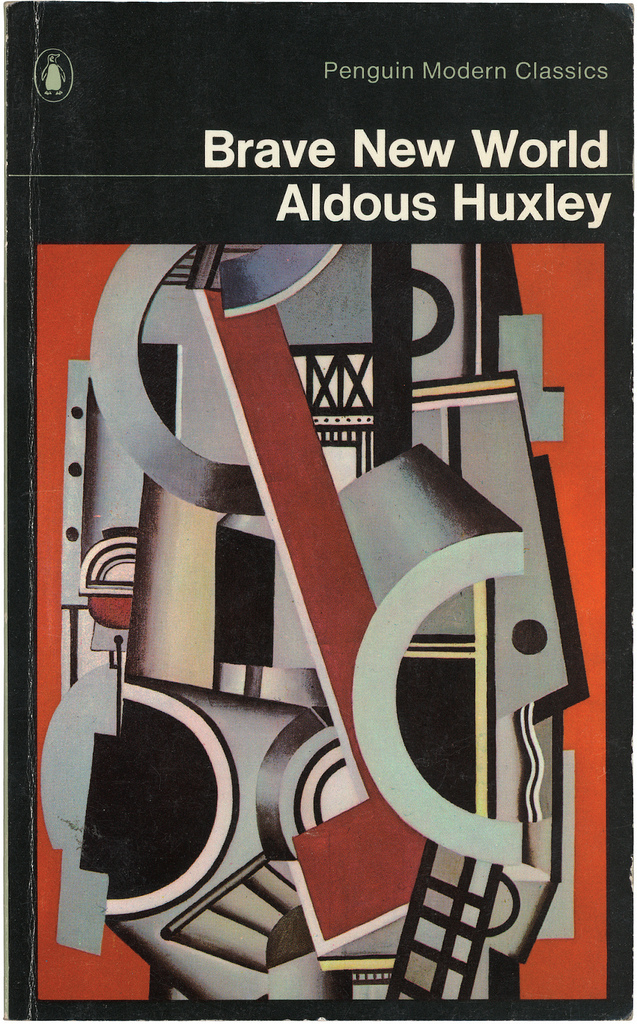

In typical dystopian fashion, we join the Aeon Flux story roughly four hundred years after an industrial-related virus has killed 99% of the world’s population. Scientist, Trevor Goodchild (Marton Csokas) has developed a cure and the Goodchild dynasty secures a home for the five million survivors in the last city on Earth, Bregna, a paradise walled off from the unrestrained wilderness that ever-threatens them. Dystopias, like Bregna, often appear utopian on the surface, exhibiting a world free of poverty, hardship and conflict, but with some fatal flaw at their core. A dystopia (“dys”=bad; “topos”=place) is a fictional society that is the antithesis of utopia. It is usually characterized by an authoritarian or totalitarian form of government or some kind of oppressive, often insiduous, social control. Other examples that depict a range of distopian societies in literature and film include: 1984, Brave New World, Fahrenheit 451, The Handmaid’s Tale, Metropolis, THX-1138, Blade Runner, and V for Vendetta. Built from scientific premise and intended only as a temporary measure, the technocratic society of Bregna continues long after its intended span as the Goodchilds attempt to deal with an internal and enduring glitch (infertility) of the “cure”. Like most imposed provisional governments, this solution to a problem (cloning) has created yet another problem (fugitive memories from the previous clone’s life).

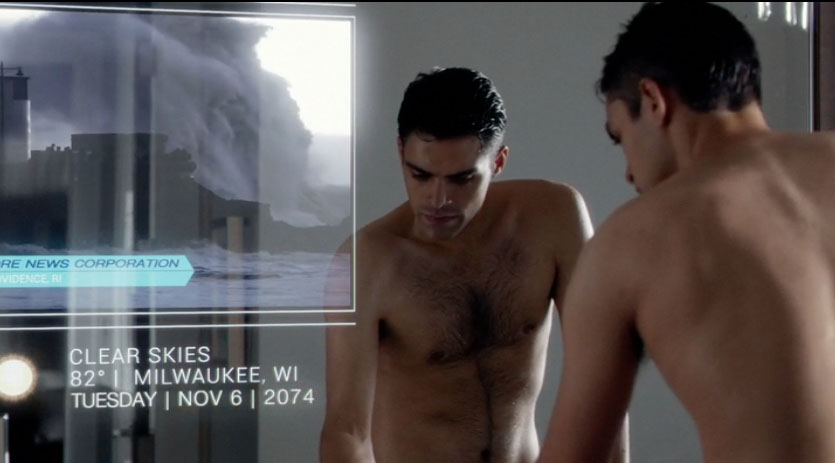

It is now 2415 and the walled society of Bregna appears utopian—clean and organized, beautiful, rich and spacious; but beneath the laughter and contentment, stirs an uneasy disquiet. Bregnans are losing sleep, having bad dreams, and are plagued by memories that don’t belong to them. Rebels who call themselves the Monicans challenge the Goodchild regime, run by Trevor and his brother Oren, and among the rebels is a highly competent and ruthless assassin, Aeon Flux (Charlize Theron), whose tools include whistle-controlled ball-bearing bombs, drugs that allow her to meet people on higher planes of existence, and interchangeable eyeballs. She is aptly named, as she serves a true agent of discord to Goodchild, the guardian of order and all that he naïvely believes is good.

“Some call Bregna the perfect society,” Aeon tells us in the opening scenes of the motion picture, “Some call it the height of human civilization…but others know better…We are haunted by sorrows we cannot name. People disappear and our government denies these crimes…But there are rebels who…fight for the disappeared. They call themselves the Monicans. I am one of them.” Several critics disliked the narrative introduction. I found that it particularly worked, by adding a reflective literary quality to the motion picture. It is noteworthy that in the original animated series, Trevor Goodchild often frames each episode with his reflections; only fitting that Aeon gets her chance in the film version. The reflective narrative of the motion picture is meant to enlighten its audience that this is not your ordinary action thriller. What follows is a fast-paced yet thoughtful story, with elements of romance, that explores notions of longevity, social structure and connection, faith and greed.

Twitchfilm.net aptly called the motion picture “biological science fiction”. Trevor’s treacherous brother Oren says: “We’ve beaten death. We’ve beaten nature.” The film’s clean organic high-tech look faithfully captures the “sense of biotech gone wild” of the TV series by exploring several paradigms inherent in a society that lives deliberately in the absence of nature’s chaos. Indeed, the lack of connectivity resonates throughout the motion picture in its exploration of friendship, family, loyalty, and purpose. When her sister is murdered in the beginning of the film supposedly by Trevor’s men (but in actuality by his scheming brother, Oren), Aeon’s mission becomes personal: “I had a family once. I had a life; now all I have is a mission.” We never learn what the animated Aeon’s motives are.

The film truly launches into stylish action and intrigue when Aeon gladly accepts a mission to assassinate Trevor, thinking that this violent act will make it all better. Instead, it unravels her, beginning with when she confronts him; finding him uncomfortably familiar and alluring, she hesitates and decides not to kill him. “What do you want?” Trevor asks her. “I want my sister back. I want to remember what it’s like to be a person.” It is indeed he—or rather what he knows—that holds the key to who she is. The key is that she, like he and all those in Bregna, is a 400 year-old copy of someone before the virus. Four hundred years ago she was the original Trevor’s wife.

Filmed in Berlin, the movie is visually stunning, from the opening shot on the steps of Sans Souci to the labrinthine wind canal used by the Nazis. Displaying an eclectic mixture of spareness and mid-century design the film is acted out in a fluid dance to Graeme Revell’s (Sin City) haunting score. The action is rivetting and seamless with both plot and underlying theme of bio-tech gone awry. Early on we are treated to a thrilling sequence of Aeon and her biotech-altered rebel colleague negotiating the security of Goodchild’s sanctuary that consists of a beautiful but deadly garden, guarded by patches of knife-sharp blades of grass and poison dart-spitting fruit trees.

Aeon champions moral ethics and single-handedly destroys the relicor, the supposetory of the clone DNA, pursuing honour at the expense of loyalty (to Goodchild) and heralding in a new age of “mortality”. The movie ends as it begins, with Aeon’s narrative: “Now we can move forward. To live once for real and then give way to people who might do it better…to live only once but with hope.” This is truly what Aeon Flux represents and what her very name embodies.

The term Aeon comes from the Gnostic notion of “Aeons” as emanations of God. Aeon also means an immeasurably long period of time; the Suntelia Aeon in Greek mythos symbolizes the catastrophic end of one age and the beginning of a new one. This is apt for our heroine, who, at least in the movie version, pretty well single-handedly destroys an old corrupt world, and heralds in a new age. Aeon was “emanated” after four hundred years by the gentle oracular Keeper of the relicor, whose original version saved her DNA and kept it hidden and safe until the right moment.

Fans of Peter Chung’s baroquely violent animated Aeon Flux will recognize some similarities between Kusama’s 2005 film adaptation and the original MTV cartoon. While admitting that the motion picture version was only based on Peter Chung’s characters (check the credits), Karyn Kusama intended to “honor [the cartoon version’s] wierdness in spirit and…pay homage to its esoteric boldness and…strange energy.” Homages to the animated series include: Aeon’s signature fly-catching with her eyelashes, demonstrating a woman extremely in tune with her body; Monican anarchists (though in the film they are subversives within Bregna rather than from an adjacent society); a virus that kills off most of the population and assassination attempt on Goodchild (Pilot); the harness worn on the torso that transports the wearer to another dimension (Utopia or Deuteranopia?); passing secret messages through a french kiss (Gravity); issues of cloning and two colleagues crossing a weaponized no-man’s land together (A Last Time for Everything). Original and movie adaptation also share at their core the exploration of the consequences and ambiguities of choices in life and the role that nature plays, subversive or otherwise.

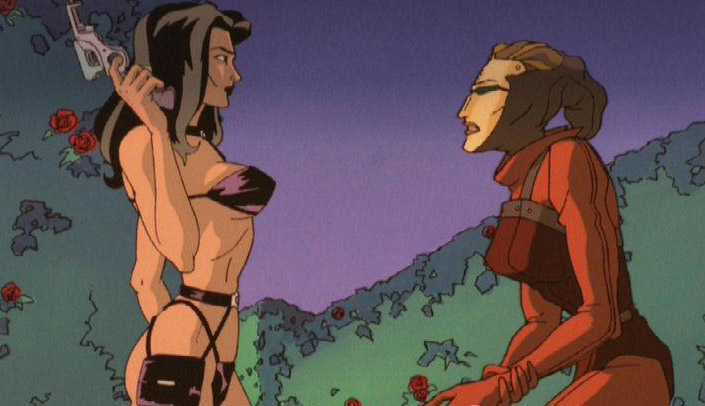

Although they share recognizable motifs and characters, the 2005 movie adaptation contrasts in some important ways from the six 5-minute shorts of 1991 and 10 half-hour episode TV series that aired in 1995. Chung’s avante garde series is set mostly in a surrealistic dark future Earth (presumably) where two communities, Bregna and Monica, are juxtaposed but separated by a wall (not unlike East and West Berlin). Bregna is a centralized scientific-planned society and Monica is Bregna’s ‘evil twin’, an anarchistic society. Chung’s innovative use of “camera angles” reminiscient of cinematography, together with a spare, graphic choreography, portrays a sprawling Orwellian industrial world. Peopled with mutant creatures, clones, and robots, it features disturbing images of dismemberment, mutilation, violent deaths and human experimentation as Chung explores post-modern notions of cloning, mind and body manipulation, and evolution through a series of subversive aggressively non-narrative pieces. On the subject of his cloning experiments (A Last Time for Everything) Goodchild says to Aeon: “My work offends you. Why? Human beings aren’t so unique, just a random arrangement of amino acids.” To which Aeon retorts, “These people you’re copying are already superfluous. You’re trafficking in excess.”

The title character in the animated version is a tall, scantily-clad anarchist (featuring the sultry voice of Denise Poirier) skilled in assassination and acrobatics, who infiltrates technocratic Bregna from the neighbouring revolutionary society of Monica. As with the movie character (elegantly portrayed by Theron), the animated Aeon is a stylish dance; completely in tune with her body. Says Chung of his creation: “The way she’s dressed, the way she looks, the way she moves was tailored to seduce the viewer to watch more, even though they may not understand at every moment what was happening.”

Despite their similar intelligence, physicality and drive, the two Aeons depart as characters. For instance, one of the major differences between original animation and adapted film is the ongoing relationship between Aeon and her nemesis/lover, Trevor Goodchild (John Rafter Lee). The sexual and intellectual tension between Flux and Goodchild is far more palpable in the TV series and does not explain itself or resolve itself like it does in the movie. The opening of the animated series describes their odd relationship, which suggests that their destinies are bound together: Aeon: “You’re out of control.” Trevor: “I take control. Who’s side are you on?” Aeon: “I take no side.” Trevor: “You’re skating the edge.” Aeon: “I am the edge.” Trevor: “What you truly want only I can give.” Aeon: “You can’t give it, you can’t even buy it and you just don’t get it.”

The Gnostic “Aeons”, emanations of God, come in male/female pairs (aptly represented by Flux and Goodchild). As with the Gnostic “Aeon pairs”, Flux and Goodchild make up inseperable parts, the yin/yang (complementary opposites) of a whole, and represent the paraxical oxymoron of chaos in order. Long-limbed and continually in fluid motion, Flux dances through Goodchild’s rigid scientific world of order with an ease that stirs both his fascination and his fury. He, in turn, enthralls her and ensnares her with his intellectual hubris. The Gnostic “Aeon” male/female pair (called syzygies) of Caen (Power) and Akhana (e.g., Love) closely parallel Goodchild and Flux as they flirt with each other in a complex dance of power and love. Their attraction/antagonism mimics the characterizations of Eris (Greek goddess of discord) and Greyface (a man who taught that life is serious and play is a sin) in the Discordian mythos. Like Eris and her golden apple, Aeon Flux stirs up trouble for Goodchild’s complacent technocratic regime, constantly challenging his hubristic notions of human evolution, perfection and even love.

The cartoon Aeon Flux—and Trevor Goodchild, for that matter—are also far more compelling than those depicted in the movie. Headstrong, foolish and selfish but also dedicated and deeply compassionate and honourable, Chung’s Aeon Flux is a paradox. She scintilates with passionate self-defined notions against an industrial tyranny, while nurturing a naïve desire for personal love; the target of both being found in one man, Trevor Goodchild. Often cruel at times, she shows moments of selfless consideration, compassion and humour. Despite her violence, perverted fetishes and lustful obsessions, she is as appealing as she is strange; a discordant rock tune, which often enough hits a resonating note that draws out one’s interest and captures one’s empathy.

In contrast to the super-hero competence and aloofness of the movie Aeon, the animated Aeon is wonderfully flawed; she is a complex paradoxical character, who makes mistakes, blundering often due to over-confidence and poor decisions (usually connected with her feelings for Trevor). Chung’s Goodchild is equally complex, and is, unlike the naïve and rather feckless scientist of the movie, a true equal to Flux’s energetic and often misplaced heroics. Kusama’s Goodchild is neither menacing nor diabolical; rather, he is a well-intentioned and watered-down version of the Machiavelian scientist that Chung created. And, though quite appealing, he is also less compelling as a result. Chung’s Goodchild is a visionary pedant, who often spouts twisted Orwellian diatribe: “That which does not kill us makes us stranger.” “The unobserved state is a fog of probabilities…” “There can be no justice without truth. But what is truth? Tell me, if you know, and I will not believe you.” Flux cuts through Goodchild’s dogma with her own one-liners—“Trevor, don’t trouble me with your thin smile”—and usually shuts him up with either a smack or a kiss.

The animated series is far more gritty and edgy than the movie version, featuring twisted eroticism and dark humor amid scenes of graphic violence. It oozes with a delicious perversity that the movie version abandoned in favour of cohesive narrative (and a PG-13 rating). Showing a healthy and irreverent disregard for that very narrative continuity, Chung’s animated series successfully makes commentary on various societal notions and behaviours through his uniquely disjointed and liberating form. Chung asserts that this plot ambiguity and disregard for continuity were meant to satirize mainstream film narratives. I think it does far more than this as art form, by providing a journalistic style of reporting the nuances and filigrees of life that gives it an immediacy hard to overlook. Chung’s apparent intention was to emphasize the futility of violence and the ambiguity of personal morality. This is best shown in his six 5-minute shorts and pilot, created in 1991. The shorts commonly featured a violent death for the title character, sometimes caused by fate, but more often due to her own incompetence.

The TV Aeon Flux flows like a subversive movement; punctuated by a series of abstract, often garish, statements on various themes of soulless biotechnology. Each episode is a vignette that explores singular questions of integrity, honour, loyalty, belief and love using the clever platform of the kiss/kill dynamic of Aeon and Trevor.

Their interactions scintillate with clever wordplay, often amid physical-play that usually involves a pointed weapon: Aeon: “You’re psychotic. You no longer have a common conscience with your fellow man.” Trevor: “I understand the will of evil…[it] is like an iron in a forge…conscience is the fire.” Aeon: “you’ve lost the substance by grasping at the shadow.” The underlying question of connectivity and what it is to be human filter through his discordant series primarily through the twining of his two main characters, both loners with little connection to anything except to one another (which they both seek and abhor). The motion picture version pursues through a more structured and lengthy narrative, the same theme of connectivity (with nature, with others of our society, with family, and our beliefs) and the consequence of living a life with out meaning, though on a far more simple level. At the end of Kusama’s movie, Aeon challenges Trevor’s assertion that cloning is their only answer for survival: “We’re meant to die. That’s what makes anything about us matter…[otherwise] we’re ghosts.” In contrast, at the end of Chung’s episode, Reraizure, Trevor closes with these words of reflection: “We are not what we remember of ourselves. We can undo only what others have already forgotten. Learn from your mistakes so that one day you can repeat them precisely.”

Kusama’s film version chose narrative coherence to make its statements by sacrificing character for story and challenging its audience cerebrally. Chung’s cartoon version challenges us more deeply, at a visceral level, through the interplay of his characters where cohesive narrative doesn’t matter. In the final analysis, the motion picture version pursues the same questions posed by Chung’s original animated version. Only, Chung isn’t so eager to provide answers, leaving both interpretation and conclusions to the individual. Both versions are mind-provoking and a celebration of excellent art. While the film’s moralistic tale resonated and lingered like a muse’s long forgotten poem, the subversive kick of the comic series (which I thankfully saw later) struck deep chords and left me breathless with questions.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

In the androcratic model, a woman “hero” often presupposes she shed her feminine nurturing qualities of compassion, kindness, tenderness, and inclusion, to express those hero-defining qualities that are typically considered “male”. I have seen too many 2-dimensional female characters limited by their own stereotype in the science fiction genre—particularly in the adventure/thriller sub-genre. If they aren’t untouchable goddesses or “witches” in a gynocratic paradigm, they are often delegated to the role of enabling the “real hero” on his journey through their belief in him: as Trinity enables Neo; Hermione enables Harry; Mary Jane enables Spiderman; Lois enables Superman; etc. etc. etc.

In the androcratic model, a woman “hero” often presupposes she shed her feminine nurturing qualities of compassion, kindness, tenderness, and inclusion, to express those hero-defining qualities that are typically considered “male”. I have seen too many 2-dimensional female characters limited by their own stereotype in the science fiction genre—particularly in the adventure/thriller sub-genre. If they aren’t untouchable goddesses or “witches” in a gynocratic paradigm, they are often delegated to the role of enabling the “real hero” on his journey through their belief in him: as Trinity enables Neo; Hermione enables Harry; Mary Jane enables Spiderman; Lois enables Superman; etc. etc. etc.

liberator for Belters but is really a terrorist revolutionary group, looking to shift the balance of power); she naively joined to help the lowly belters achieve justice and a voice in the oppressive squeeze by Martian and Earth corporate interests. In “Back to the Butcher”, a colleague of Julie’s relates how she selflessly helped injured minors on Calisto in a tunnel collapse with cadmium poisoning: “I never saw her shed a tear over the fact that she’d have to take anti-cancer meds for the rest of her life.” The only time she cried, he shares, was when she was acknowledged as being a true “beltalowda.”

liberator for Belters but is really a terrorist revolutionary group, looking to shift the balance of power); she naively joined to help the lowly belters achieve justice and a voice in the oppressive squeeze by Martian and Earth corporate interests. In “Back to the Butcher”, a colleague of Julie’s relates how she selflessly helped injured minors on Calisto in a tunnel collapse with cadmium poisoning: “I never saw her shed a tear over the fact that she’d have to take anti-cancer meds for the rest of her life.” The only time she cried, he shares, was when she was acknowledged as being a true “beltalowda.”

from a higher calling, not from lust for power or self-serving greed. She’s seeks the truth. And, like Miller, she struggles with a conscience. Chrisjen is a complex and paradoxical character. Her passionate and unrelenting search for the truth together with unscrupulous methods, make her one of the most interesting characters in the growing intrigue of The Expanse. Avasarala is a powerful character on many levels—none the least in her potent presence (thanks to Shohreh Aghdashloo’s powerful performance); when Avasarala walks into a scene, all eyes turn to her.

from a higher calling, not from lust for power or self-serving greed. She’s seeks the truth. And, like Miller, she struggles with a conscience. Chrisjen is a complex and paradoxical character. Her passionate and unrelenting search for the truth together with unscrupulous methods, make her one of the most interesting characters in the growing intrigue of The Expanse. Avasarala is a powerful character on many levels—none the least in her potent presence (thanks to Shohreh Aghdashloo’s powerful performance); when Avasarala walks into a scene, all eyes turn to her.

operative and she finds herself ironically defending the Belt and Belters in the struggle between Earth and Mars. “We need to stick together,” she tells fellow Belter Miller and helps Fred Johnson’s team. Driven to help those in need, Naomi selflessly puts herself in harm’s way to save Belters used as lab rats on Eros or those left to die on Ganymede after a Mars and Earth skirmish. In an intimate moment with Holden after the atrocity on Eros with the proto-molecule experiment, Naomi reminds him: “We did not choose this but this is our fight now. We’re the only ones who know what’s going on down there; we’re the only ones with a chance to stop it.”

operative and she finds herself ironically defending the Belt and Belters in the struggle between Earth and Mars. “We need to stick together,” she tells fellow Belter Miller and helps Fred Johnson’s team. Driven to help those in need, Naomi selflessly puts herself in harm’s way to save Belters used as lab rats on Eros or those left to die on Ganymede after a Mars and Earth skirmish. In an intimate moment with Holden after the atrocity on Eros with the proto-molecule experiment, Naomi reminds him: “We did not choose this but this is our fight now. We’re the only ones who know what’s going on down there; we’re the only ones with a chance to stop it.”

Station. A complex character with mysterious connections and intuitive skills for people, Drummer gives one the impression that she can nimbly navigate between hard-line OPA and Fred’s Earther-version of OPA justice for Belters. In “Pyre”, she shows her mettle when—after being shot and held hostage by a militant faction on Tycho—she finds the strength to summarily execute them.

Station. A complex character with mysterious connections and intuitive skills for people, Drummer gives one the impression that she can nimbly navigate between hard-line OPA and Fred’s Earther-version of OPA justice for Belters. In “Pyre”, she shows her mettle when—after being shot and held hostage by a militant faction on Tycho—she finds the strength to summarily execute them.

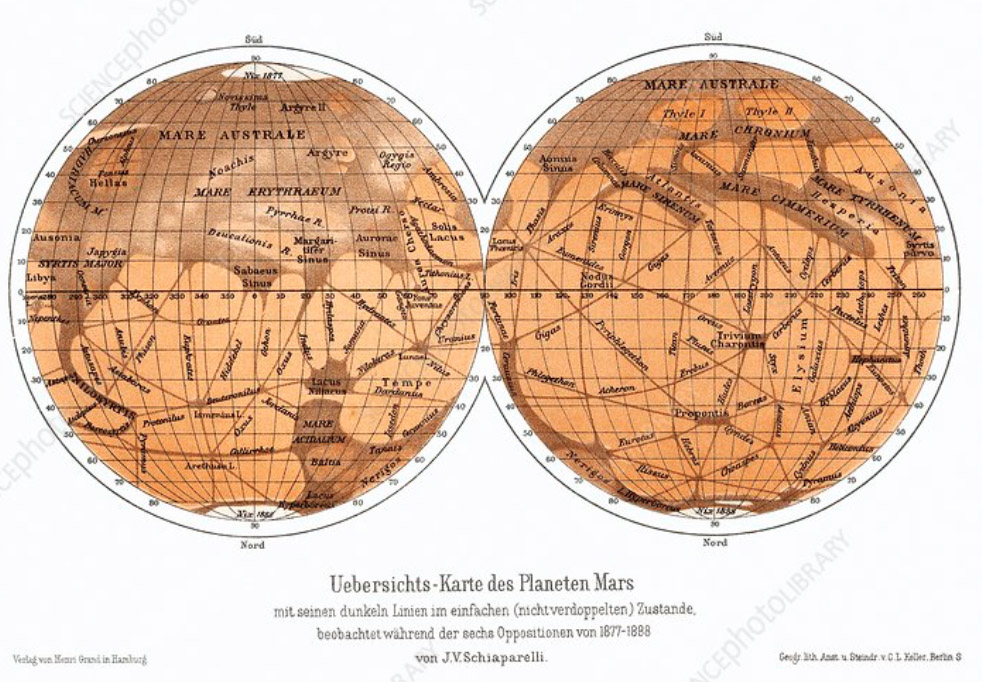

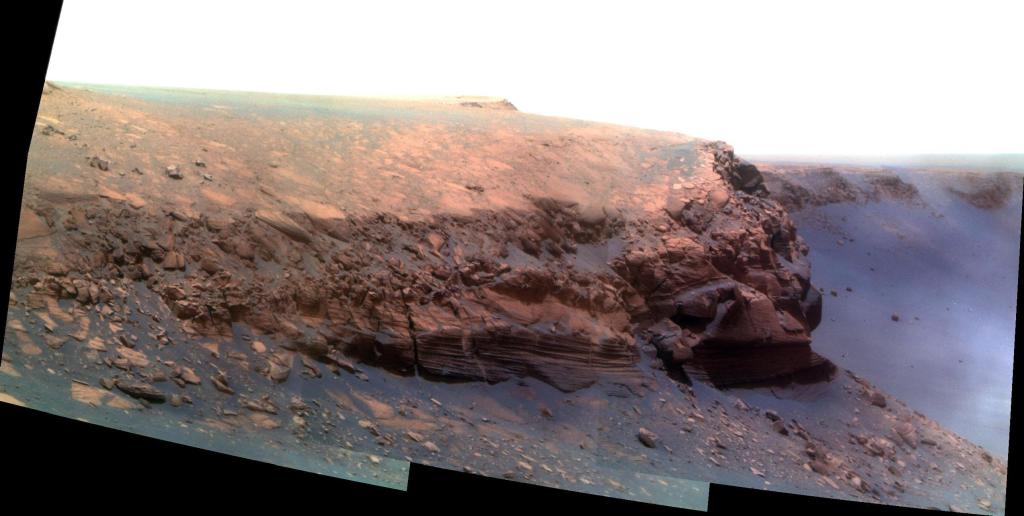

Bobbie Draper (Frankie Adams) is a staunch hard-fighting Martian marine who dreams of a terraformed Mars with lakes and vegetation and breathable atmosphere. Because of Earth’s Vesta blockade, Draper realizes that she will not realize her childhood dream of seeing Mars “turned from a lifeless rock into a garden.” The blockade forced Mars to ramp up its military at the expense of terraforming. Draper laments that, “with all those resources moved to the military, none of us will live to see an atmosphere over Mars” and bears a strong resentment against Earth. However, when Bobbie discovers her own government’s culpability with an Earth weapons manufacturer that used her own marines as guinea pigs, she chooses honour over loyalty and defects to seek justice.

Bobbie Draper (Frankie Adams) is a staunch hard-fighting Martian marine who dreams of a terraformed Mars with lakes and vegetation and breathable atmosphere. Because of Earth’s Vesta blockade, Draper realizes that she will not realize her childhood dream of seeing Mars “turned from a lifeless rock into a garden.” The blockade forced Mars to ramp up its military at the expense of terraforming. Draper laments that, “with all those resources moved to the military, none of us will live to see an atmosphere over Mars” and bears a strong resentment against Earth. However, when Bobbie discovers her own government’s culpability with an Earth weapons manufacturer that used her own marines as guinea pigs, she chooses honour over loyalty and defects to seek justice.

The Secretary General (who she had a previous friendship that soured over some dubious event) has called Anna in to write a stirring speech to unite Earth behind the war erupting between Earth and Mars. Anna enters the political intrigue with naive hope and is badly used; but her inner strength, keen intelligence and courage propels her on an amazing trajectory of influence to the outer reaches of the solar system where first contact is imminent. Like a quiet summer rainstorm, Anna brings a fresh perspective on heroism through faith, hope and inclusion.

The Secretary General (who she had a previous friendship that soured over some dubious event) has called Anna in to write a stirring speech to unite Earth behind the war erupting between Earth and Mars. Anna enters the political intrigue with naive hope and is badly used; but her inner strength, keen intelligence and courage propels her on an amazing trajectory of influence to the outer reaches of the solar system where first contact is imminent. Like a quiet summer rainstorm, Anna brings a fresh perspective on heroism through faith, hope and inclusion.

to name just a few. The gender of the hero I empathized with was irrelevant. What remained important was their sensibilities and their actions of respect and integrity on behalf of humanity, all life and the planet.

to name just a few. The gender of the hero I empathized with was irrelevant. What remained important was their sensibilities and their actions of respect and integrity on behalf of humanity, all life and the planet.

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit

Nina Munteanu is an ecologist and internationally published author of award-nominated speculative novels, short stories and non-fiction. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit