That day may seem like science fiction or the far future, but as William Gibson famously proclaimed, “The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.”

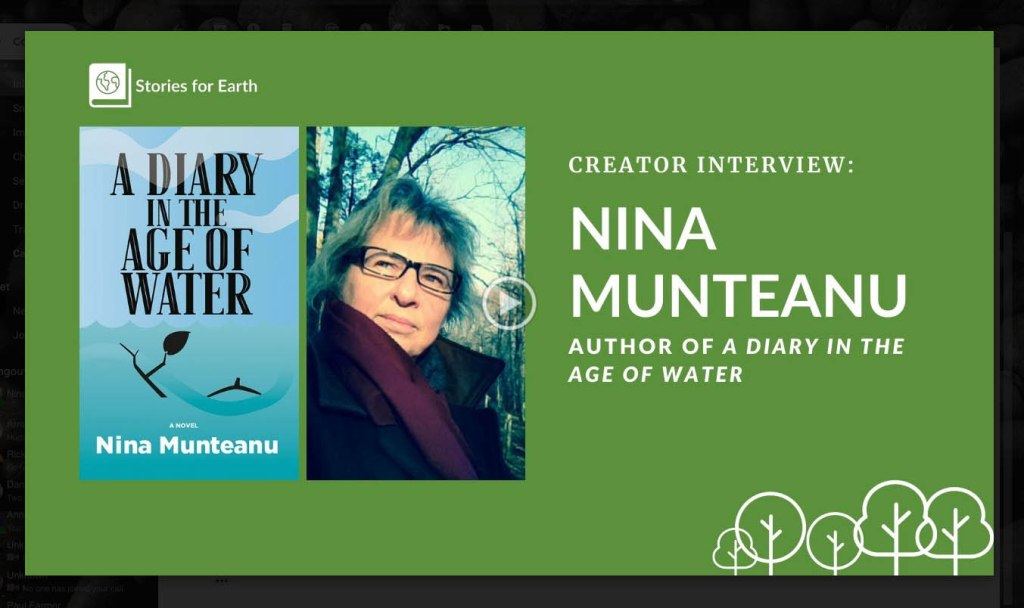

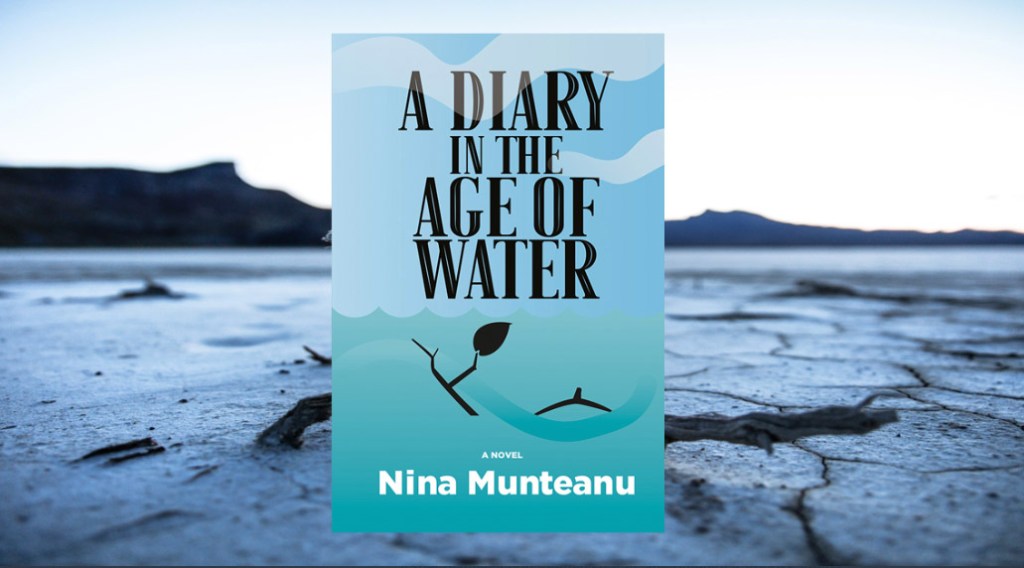

This is partly why I’ve been recently writing speculative (mundane) science fiction in which components of fiction blur with non-fiction. In a recent interview on the SolarPunk Magazine Podcast, I discussed with hosts Justine and Bria how my recent novel A Diary in the Age of Water blurred fiction with non-fiction. The novel achieved this through the use of a diary to create a gritty realism in a mundane narrative hard to put down. The intention was to achieve personal relevance for the reader to what was going on, particularly with climate change—a water-driven phenomenon. In The Temz Review, Marcie McCauley postulated that “[Munteanu] does not appear to view fiction and non-fiction as separate territories; or, if she does, then this book is a bridge between them.” I had to laugh when I read this; “she gets me,” I concluded.

In the near-future of A Diary in the Age of Water, Canada has privatized its water utilities after the Conservative Party comes into power, and a giant company called CanadaCorp removes municipal water connections from people’s homes and imposes strict water rations, all while selling off Canada’s precious water to US states like California that would otherwise be uninhabitable.

In her entry for July 13, 2049, Lynna the diarist writes:

“Today CanadaCorp announced that the collection of rainwater was illegal. As of today, I could be arrested for using my rain catcher and cistern. I’ve decided to continue using the cistern, and I’ve warned Hildegard not to breathe a word to anyone at school about what we’re doing with the water. Thankfully, I have time to train her in the art of subterfuge before she starts Grade Two in the fall.”

Nina Munteanu, A Diary in the Age of Water

What follows in the novel is complete commodification of water and further restrictions for citizens in the form of house tap closures and daily water quantity quotas from paying public water taps. No form of water is free or available without payment. And if you can’t pay, well…

Dizzy and shivering in the blistering heat, Hilda shuffles forward with the snaking line of people in the dusty square in front of University College where her mother used to teach. The sun beats down, crawling on her skin like an insect. She’s been standing for an hour in the queue for the public water tap… The man behind Hilda pushes her forward. She stumbles toward the tap and glances at the wCard in her blue-grey hand. Her skin resembles a dry riverbed.

Heart throbbing in her throat, Hilda fumbles with the card and finally gets it into the reader. The reader takes it. The light screams red. Her knees almost give out. She dreaded this day…

A tiny water drop hangs, trembling, from the wTap faucet mouth, as if considering which way to go: give in gravity and drop onto the dusty ground or defy it and cling to the inside of the tap. Hilda lunges forward and touches the faucet mouth with her card to capture the drop. Then she laps up the single drop with her tongue. She thinks of Hanna and her throat tightens.

The man behind her grunts. He barrels forward and violently shoves her aside. Hilda stumbles away from the long queue in a daze. The brute gruffly pulls out her useless card and tosses it to her. She misses it and the card flutters like a dead leaf to the ground at her feet. The man shoves his own card into the pay slot. Hilda watches the water gurgle into his plastic container. He is sloppy and some of the water splashes out of his container, raining on the ground. Hilda stares as the water bounces off the parched pavement before finally pooling. The ache in her throat burns like sandpaper and she wavers on her feet. The lineup tightens, as if the people fear she might cut back in. She stares at the water pooling on the ground, glistening into a million stars in the sunlight…and knows she is dying of thirst…

Nina Munteanu, The Way of Water / la natura dell’acqua

This excerpt from my bilingual short story “The Way of Water / la natura dell’acqua” (Mincione Edizioni, 2016) follows the life of Hilda Dresden, daughter of Lynna, the diarist in “A Diary in the Age of Water.”

Science fiction, you think…

Far future, you think…

Think again…

In 2010, Mike Adams of Natural News reported that collecting rainwater was now illegal in several states of the USA. Utah, Washington and Colorado had outlawed individuals from collecting rainwater on their own properties because, according to officials, that rain belonged to someone else.

In 2015, thousands of citizens in two of America’s poorest cities, Detroit and Baltimore, had their water shut off for being behind on their water bills (which had been sharply increased).

Both are inhumane examples of government-imposed oppression over what should be a public and free resource: water.

Maude Barlow, the Chairperson of the Council of Canadians, writes in Boiling Point of the water crisis in Canada—perhaps our best kept secret, considering that Canada is supposedly so water-rich. Are we giving it all away? And what of our indigenous communities, some of whom have not had potable water for decades?

So, I agree with Gibson about the future not being evenly distributed. This is because the present isn’t evenly distributed. Much of this disparity arises from an extractive and exploitive mentality and practice. One that commodifies what needs to remain free and available for all users. Capitalism ensures an uneven future by focusing on fear and stressing competition, separation, and exclusion.

In his book Designing Regenerative Cultures Daniel Christian Wahl talks about changing our evolutionary narrative from one based on fear defined by a perception of scarcity, competition, and separation to one based on love defined by a perception of abundance, a sense of belonging, collaboration and inclusion.

And moving forward we can take a lesson from Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, who talks about a gift economy—an economy of abundance—whose basis lies in recognizing the value of kindness, sharing, and gratitude in an impermanent world.

This is what she says: “Climate change is a product of this extractive economy and is forcing us to confront the inevitable outcome of our consumptive lifestyle, genuine scarcity for which the market has no remedy. Indigenous story traditions are full of these cautionary teachings. When the gift is dishonored, the outcome is always material as well as spiritual. Disrespect the water and the springs dry up. Waste the corn and the garden grows barren. Regenerative economies which cherish and reciprocate the gift are the only path forward. To replenish the possibility of mutual flourishing, for birds and berries and people, we need an economy that shares the gifts of the Earth, following the lead of our oldest teachers, the plants.”

So, “The Day We’re Not Allowed to Drink Water…”

…Let that day never come.

Make it so…

References:

Barlow, Maude. 2016. “Boiling Point: Government Neglect, Corporate Abuse, and Canada’s Water Crisis.” ECW Press, Toronto. 312pp.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2020. “The Serviceberry, An Economy of Abundance.” Emergence Magazine, December 10, 2020.

Munteanu, Nina. 2016. “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water.” Mincione Edizioni, Roma. 114pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2020. “A Diary in the Age of Water.” Inanna Publications, Toronto. 300pp.

Wahl, Daniel Christian. 2016. “Designing Regenerative Cultures.” Triarchy Press Ltd. 288pp.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.