“Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.”—Rosa Luxemburg, 1915

.

I wrote my first novel in 1969 when I was fifteen. Caged in World was a hundred-page speculative story about a world that had moved “inside” to escape the ravages of a post climate-change environment. It would later become Book 2 of The Icaria Trilogy. I was already disillusioned with my world. I saw how corporations and governments and society in general—individuals around me—‘othered’ the environment by either treating it with disrespect and apathy or outright ignoring it in a kind of torpor of obliviousness. As though it didn’t exist.

.

I remember being chastised by a school teacher for thinking globally about what was happening to the planet at our hands: worldwide deforestation (e.g., clearcutting the old-growth forests of Canada), infilling saltwater and freshwater marshes, massive use of pesticides and fertilizers, contamination of lakes, unregulated mining and toxic pollution, and ultimately climate change. Stick to local concerns, he advised me; recycling and such.

I remember wondering if I was just being weird. That my odd sensibility for the planet-entire was just a nina-thing. I prayed that I was not alone and it wasn’t just a nina-thing.

.

(Photo: Nina Munteanu, Salk Institute, California)

.

For a description of how the books of the trilogy came to be (for instance, they were published in backward order!) see my article entitled “Nina Munteanu Reflects on Her Eco-Fiction Journey at Orchard Park Secondary School”.

Throughout high school and university, I read scientific papers, news articles and books on revolution. I became a student of climate change long before the term entered the zeitgeist. I studied industrial capitalism and its roots in neoliberalism and colonialism. I noted how the post-war expansion of capitalism shifted from Fordist mass production to flexible automation, technology and AI. I saw the rise of multinational corporations, income inequality, and the commodification of everything—from water to human beings (Foucault’s homo economicus).

.

I pursued a university degree in ecology and limnology to study and help protect the environment and educate industry and their governments in the process. I became an expert on water. See my book Water Is…The Meaning of Water, which celebrates water from twelve perspectives (and got a shout out from Margaret Atwood!).

.

I soon concluded that a hegemony that follows the economic system of late capitalism inevitably commodifies and ‘others’ with ruthless purpose. Once something (or someone) is commodified, they are given a finite value and purpose outside their own existence. They become an object, a symbol to use and trade. They become a resource to manipulate, exchange, and dispose of with impunity. And through this surrender to utility, they become ‘othered.’ The consumer. The trees of the forest. Water. Homo sacer*. Each has a role to play in the late capitalist narrative of digital abundance and physical scarcity.

Capitalism hasn’t been kind to the environment. Economic pundits and sociologists insist that Capitalism is devolving. But what will replace it? Cloud capital? Technofeudalism? Something else?

.

Deep Ecology* & Gaia’s Revolution

.

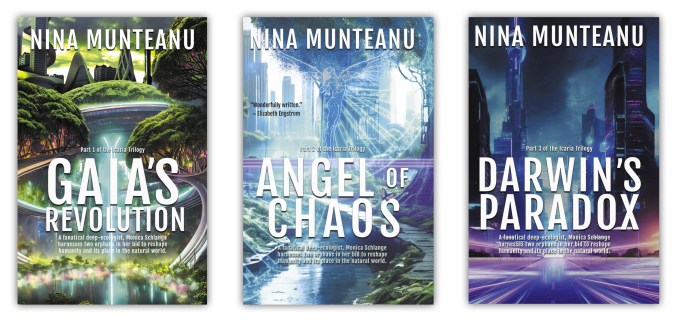

My three Icaria novels—starting with Gaia’s Revolution, (the first of The Icaria Trilogy, releasing March 10, 2026, by Dragon Moon Press)—chronicle the collapse of a capitalist society in Canada as climate change, water shortages, habitat destruction, plague and a failing technology devastate the Canadian population.

.

Gaia’s Revolution (Book 1 of The Icaria Trilogy) explores a transition in Canada from semi-socialized capitalist system to a technocratic* meritocracy of technologists and scientists. Triggered by catastrophic environmental and sociological tipping points and following violent revolution, a dictatorship of deep ecologists* called Gaians seize power. By the end of the book, enclosed cities called Icarias* now populate North America. Separated from their environment, humans now live inside domes protecting them from a hostile and toxic environment.

.

In truth, the deep ecologists are keeping people “inside” not to protect humanity from a toxic wasteland but to protect the environment from a toxic humanity.

.

How realistic is this vision? Well, it is science fiction, after all, and though it takes liberties with its narrative, it is science-based and ultimately draws on precedent. As Margaret Atwood so astutely attested of her cautionary SF book The Handmaid’s Tale: “I didn’t put in anything that we haven’t already done, we’re not already doing, we’re seriously trying to do, coupled with trends that are already in progress.”

Science fiction is itself powerful metaphor; it is the fiction of political and social allegory or satire and makes astute social commentary about a world and civilization: how it has come to be, how it works—or doesn’t—and how it may evolve.

So, it is visionary and predictive? I prefer to think as Ray Bradbury:

.

“The function of science fiction is not only to predict the future, but to prevent it.”–Ray Bradbury

.

.

References:

Angus, Ian. 1012. “The Spectre of 21st Century Barbarism.” Climate & Capitalism, August 20, 2012.

Atwood, Margaret. 2004. “The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake ‘In Context'”. PMLA. 119 (3): 513–517.

Atwood, Margaret. 2018. “Margaret Atwood on How She Came to Write The Handmaid’s Tale”. Literary Hub. April 25, 2018.

Bradbury, Ray. 1991. “Yestermorrow: Obvious Answers to Impossible Futures” and “Beyond 1984: The People Machines” by Ray Bradbury, dated 1982, Page 155, Joshua Odell Editions: Capra Press, Santa Barbara, California.

Foucault, Michel. 2010. “The Birth of Biopolitics (Naissance de la biopolitique): Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979.” Picador. 368pp.

Luxemburg, Rosa. 1915. “The Junius Pamphlet: The Crisis in the German Democracy”, Marxist.org.

Munteanu, Nina. 2026. “Gaia’s Revolution, Part 1 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 369 pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2010. “Angel of Chaos, Part 2 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 518 pp.

Munteanu, Nina. 2007. “Darwin’s Paradox, Part 3 of Icaria Trilogy.” Dragon Moon Press, Calgary, AB. 294 pp.

Neuman, Sally. 2006. “‘Just a Backlash’: Margaret Atwood, Feminism, and The Handmaid’s Tale“. University of Toronto Quarterly. 75 (3): 857–868.

Sessions, George, Bill Devall. 2000. “Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered.” Gibbs Smith. 267pp.

Skinner, B.F. 1948. “Walden Two” The Macmillan Company, New York. 301pp.

Streeck, Wolfgang. 2014. “How Will Capitalism End?” New Left Review 2 (87): 47p.

.

Terminology:

*Deep Ecology: An environmental philosophy and social movement advocating that all living beings have intrinsic value, independent of their utility to human needs. Coined by Arne Næss in 1972, it promotes a holistic, ecocentric worldview—often termed “ecosophy”—that demands radical, structural changes to human society to prioritize nature’s flourishing.

*Homo sacer: a figure from Roman law denoting a person excluded from society who is outside human law (can be killed) and divine law (cannot be sacrificed). The term represents “bare life”: stripped of political rights, legal protection, and social value. Philosopher Giorgo Agamben popularized the term to describe individuals excluded from the political community, such as refugees, stateless persons, or camp detainees. The term illustrates the power of a sovereign in deciding which lives are worthy of protection and which are not.

*Icaria: the name of Étienne Cabet’s utopia. Cabet was a French lawyer in Dijon, who published his novel Voyage en Icarie in 1839. The novel was a sort of manifesto-blueprint of utopian socialism, with elements of communism (abolished private property and individual enterprise), influenced by Fourierist and Owenite thinking. Key elements, such as the four-hour work day, are reflected in B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two. Cabet’s novel explores a society in which capitalist production is replaced by workers’ cooperatives with a focus on small communities.

*Letzte Generation: a prominent European climate activist group, founded in 2021, known for its acts of civil disobedience—such as roadblocks, defacing art, and vandalizing structures—to pressure governments on climate action. The term was chosen because they considered themselves to be the last generation before tipping points in the earth’s climate system would be reached. They are mostly active in Germany, Italy, Poland and Canada. In Germany, they have faced accusations of forming a criminal organization, leading to police raids.

*Technocracy: A form of government in which the decision-maker(s) are selected based on their expertise in a given area; any portion of a bureaucracy run by technologists. Technocracies control society or industry through an elite of technical experts. The term was initially used to signify the application of the scientific method to solving social problems.

.

Nina Munteanu is an award-winning novelist and short story writer of eco-fiction, science fiction and fantasy. She also has three writing guides out: The Fiction Writer; The Journal Writer; and The Ecology of Writing and teaches fiction writing and technical writing at university and online. Check the Publications page on this site for a summary of what she has out there. Nina teaches writing at the University of Toronto and has been coaching fiction and non-fiction authors for over 20 years. You can find Nina’s short podcasts on writing on YouTube. Check out this site for more author advice from how to write a synopsis to finding your muse and the art and science of writing.

.